Executive Summary

advertisement

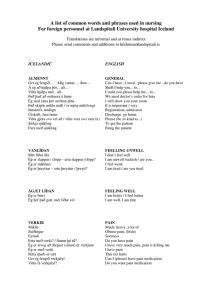

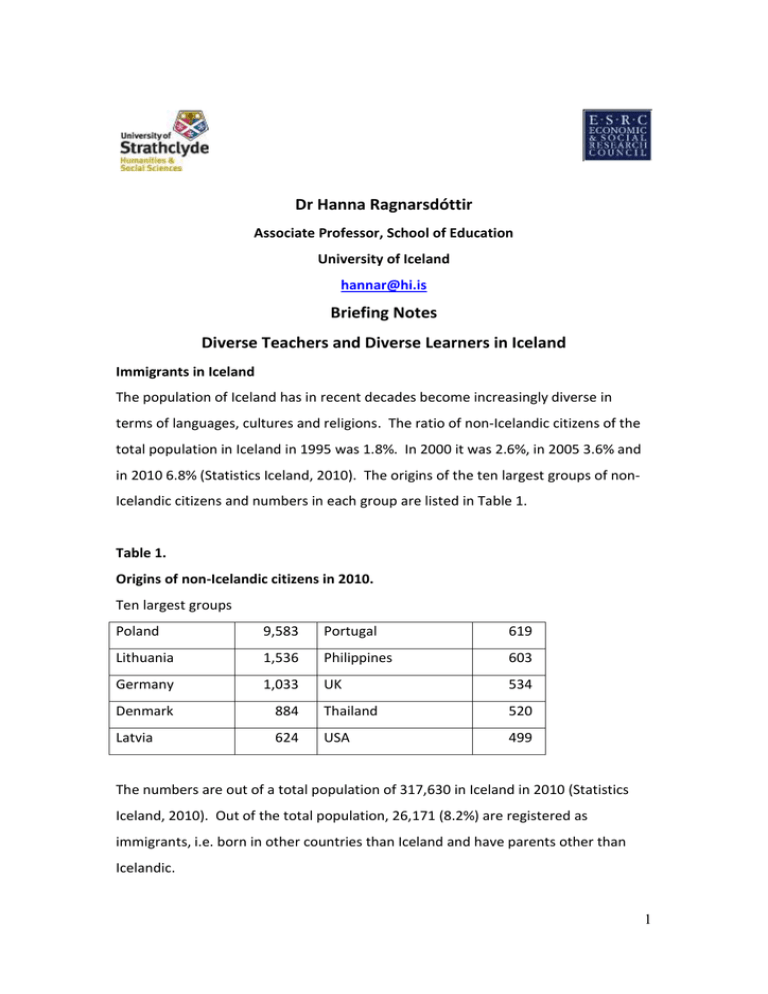

Dr Hanna Ragnarsdóttir Associate Professor, School of Education University of Iceland hannar@hi.is Briefing Notes Diverse Teachers and Diverse Learners in Iceland Immigrants in Iceland The population of Iceland has in recent decades become increasingly diverse in terms of languages, cultures and religions. The ratio of non-Icelandic citizens of the total population in Iceland in 1995 was 1.8%. In 2000 it was 2.6%, in 2005 3.6% and in 2010 6.8% (Statistics Iceland, 2010). The origins of the ten largest groups of nonIcelandic citizens and numbers in each group are listed in Table 1. Table 1. Origins of non-Icelandic citizens in 2010. Ten largest groups Poland 9,583 Portugal 619 Lithuania 1,536 Philippines 603 Germany 1,033 UK 534 Denmark 884 Thailand 520 Latvia 624 USA 499 The numbers are out of a total population of 317,630 in Iceland in 2010 (Statistics Iceland, 2010). Out of the total population, 26,171 (8.2%) are registered as immigrants, i.e. born in other countries than Iceland and have parents other than Icelandic. 1 Students Numbers of pupils in compulsory schools having another mother tongue than Icelandic in 2009 were 2,314 (5.4%) out of a total number of 42,929 pupils in Icelandic compulsory schools. These pupils had 43 different mother tongues (in the case of other 33 students mother tongue is not specified). Numbers of children in preschools having another mother tongue than Icelandic in 2009 were 1,614 (8.6%) out of a total number of 18,716 children in Icelandic preschools. These children had altogether 41 different mother tongues (in the case of other 80 children mother tongue is not specified). The numbers of children having another mother tongue than Icelandic vary greatly between schools and areas in Iceland. Teachers The backgrounds of teachers in Iceland are not officially registered, so official demographics in terms of mother languages and ethnicities are not available. Other factors such as gender, education, age and residence, on the other hand, are documented. However, detailed research in Iceland has indicated the total numbers and ethnicities of teachers in Iceland. Thus, a study conducted in 2005-6 (Lassen, 2007) reported 84 internationally educated teachers in Icelandic compulsory schools (constituting 2% of the teacher population in Iceland). The teachers originated in 29 different countries in all continents. According to research, an undefined number of internationally educated teachers in Iceland are employed in other jobs than teaching. Thus, an ongoing study in a Polish school in Iceland shows that most of the 20 qualified Polish teachers employed there are not employed as teachers in Icelandic schools during the week and only work as qualified teachers on Saturdays in the Polish school (Ragnarsdóttir & Zielińska, forthcoming; Szkoła Polska w Reykjaviku, 2010). Similarly, findings from a recent survey among immigrants have indicated that 50% of employed immigrants have jobs where their education is not 2 relevant or applied. And 74% of immigrants in the same survey have not tried to have their education accredited (Félagsvísindastofnun HÍ & Fjölmenningarsetur, 2009). According to research, there are more internationally educated teachers and teacher assistants working in preschools than in compulsory schools in Iceland although their numbers are undefined (Ragnarsdóttir, 2010). The Ministry of Education, Science and Culture (2011) in Iceland issues authorization for the professions of Preschool Teachers, Compulsory School Teachers and Upper Secondary School Teachers. The ministry does not provide courses on acclimatization for internationally educated teacher. Neither do universities. However, a number of immigrants with university education are registered in teacher training programs at the University of Iceland (Háskóli Íslands, 2010). Icelandic references Félagsvísindastofnun HÍ og Fjölmenningarsetur. (2009). Innflytjendur á Íslandi. Viðhorfskönnun. Retrieved January 19, 2011, from http://www.fel.hi.is/sites/files/fel/Innflytjendur_skyrsla.pdf Lassen, B. H. (2007). Í tveimur menningarheimum: Reynsla og upplifun kennara af erlendum uppruna af því að starfa í grunnskólum á Íslandi. Unpublished master’s thesis, Iceland University of Education, Reykjavík, Iceland. Relevant references in English Háskóli Íslands. (2010). Teaching studies, diploma programme. Retrieved January 19, 2011, from https://ugla.hi.is/kennsluskra/index.php?tab=skoli&chapter=content&id=17578&ken nsluar=2010 Jónsdóttir, E. S. & Ragnarsdóttir, H. (2010). Multicultural education in Iceland: vision or reality? Intercultural Education, 21(2), 153–167. Ministry of Education, Science and Culture. (2011). Licence Application. Retrieved January 19, 2011, from http://eng.menntamalaraduneyti.is/licence/ Ragnarsdóttir, H. (2008). Collisions and continuities: Ten immigrant families and their children in Icelandic society and schools. Saarbrücken: VDM Verlag Dr. Müller. Ragnarsdóttir, H. (2010). Internationally educated teachers and student teachers in Iceland: Two qualitative studies. Canadian Journal of Educational Administration and 3 Policy, 100 (Special Issue: Educational policy and internationally educated teachers). Retrieved January 19, 2011, from http://www.umanitoba.ca/publications/cjeap/articles/Ragnarsdottir-iet.html Ragnarsdóttir, H. & Zielińska, M. (forthcoming). The Polish school in Iceland. Experiences of students and teachers. Statistics Iceland. (2010). Retrieved January 19, 2011, from http://www.statice.is/ Szkoła Polska w Reykjaviku/Polish school in Reykjavik. (2010). Personnel. Retrieved May 24, 2010, from http://www.polskaszkola.is/ 4