Aquinas' Epistemology

advertisement

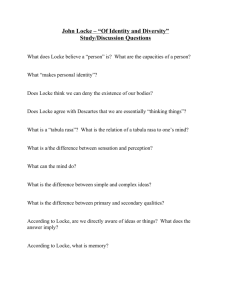

St. Thomas Aquinas’ Epistemology • Life – Born 1225 – Son of a Count – Joined the then new, mendicant religious order, the Dominicans, in 1244 – Studied in Cologne, Germany under St. Albert the Great. Received Doctorate in 1256. – Taught at the Sorbonne (the University of Paris) 1256-1259 & 1269-1272 – Taught at the University of Naples 1272-1274 – Died 1274 while on journey to a Church council. – Canonized 1323 • Influence – The leading philosopher of the Aristotelian revival in Europe during the High Middle Ages. – Philosopher of Common Sense. – Sought to integrate Aristotelian philosophy with Christianity. – Greatest work Summa Theologica, written 1265-1272 and left unfinished at his death. – Portion of the Summa dealing with epistemology written around 1268. – As with all his philosophy, Aquinas’ epistemology rooted in Aristotle’s. • Locke’s First Mistake – “[B]efore I proceed on to what I have thought on this subject, I must here, in the entrance, beg pardon of my reader for the frequent use of the word idea, which he will find in the following treatise. It being that term which, I think, serves best to stand for whatsoever is the object of the understanding . . . .” John Locke, An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding (1690) – Locke maintains that the objects of human knowledge, i.e. what humans know, are ideas. – Aquinas’ anticipates Locke’s view: • “Some have asserted that our intellectual faculties know only the impression made on them . . . . According to this theory, the intellect understands only its own impression, namely, [its idea].” Summa Theologica, I, 85, ii – Locke’s view about the object of knowledge leads to his Representative Theory of Perception, i.e. that, within the minds of humans, there are ideas that are representations, or copies, of material objects. – Now, when you think about it, it’s rather strange for Locke to say that what humans know are ideas. – In ordinary language humans say, for example, “I see the table.” That statement, on the face of it, indicates the object of sight is the table. – On Locke’s view, however, the object of sight is not really the table but an idea of the table. – Locke’s view leads to the Egocentric Predicament, i.e. problem of not being able to tell whether the idea of the table accurately corresponds to the table or, for that matter, anything else. • “If all we knew . . . directly were our own ideas, skepticism would be inevitable . . . ; for, we would be like prisoners in jail cells, seeing only pictures of the outside world on TV screens and never able to get out of jail and see the real world directly to know whether the TV images are true or false.” Peter Kreeft, Footnote 84 in Summa of the Summa, p. 324 – Another problem with Locke’s view is that it leads, inevitably, as we have seen, to relativism. • “[This view of the object of knowledge] is untrue, because it would lead to the opinion of the ancients [the Protagorians] who maintained that “whatever seems, is true” [Aristotle, Metaphysics. iii. 5], and that, consequently, contradictories are true simultaneously. For, if the faculty knows its own [idea] only, it can judge of that only . . . . Thus, every opinion would be equally true . . . .” Summa, I, 85, ii • In this response, we see how Aquinas is a Philosopher of Common Sense. • He takes it to be common sense that inconsistent claims cannot all be true, e.g. ‘John’s birthday is December 2’ and ‘John’s birthday is December 3.’ • He does not reject the common sense notion of truth, as the Post-Modernists do, so that inconsistent claims can all be true. • Rather, he rejects any premise that leads to a conclusion contrary to common sense. • In this case, Aquinas rejects Locke’s premise that ideas are the objects of knowledge. – Since Aquinas rejects Locke’s premise that ideas are the objects of knowledge, what does he believe are the objects of knowledge? – For Aquinas, the objects of knowledge, in the first instance, are the external, material objects that humans know through perception. – As indicated before, this view accords better with ordinary language. – Humans say “I see the table,” not “I see an idea which is a copy of the table.” – Since Aquinas’ view accords better with ordinary language, it, thereby, accords better with common sense. – Thus, in his judgment, Aquinas’ view is superior to Locke’s – Ideas (or, as Aquinas prefers, phantasms) play a role in perception, but not the role Locke assigned to them. – Phantasms, or ideas, are NOT what (id quod) humans know; rather, they are the means by which (id quo) humans know. – To put it metaphorically, phantasms (ideas) are not what the human mind knows; rather, they are the “windows” by means of which the human mind becomes aware of the material objects of the external world. – With this understanding of the role that ideas play in perception, Aquinas avoids Post-Modernism. • Locke’s Second Mistake – Recall Locke’s metaphor for the human mind. – It is a tabula rasa, a blank slate on which experience “writes.” – By this image, Locke indicates that the human mind is entirely passive. – In coming to know, the human mind does NOT do anything. – It just sits there, like a blank table, and lets experience “write” ideas on it. – This view of how humans come to know is at odds with the way humans normally speak. – For example, humans say “I see the table.” This indicates that I am actively doing something rather than just sitting passively, like a blank tablet, while something is done to me. – As indicated before, Aquinas maintains that an analysis of how humans come to know according better with ordinary language would be a more common sense analysis and, therefore, a better one. – Thus, in Aquinas’ analysis of how humans come to know, the mind is active, not passive. – The Theory of Abstraction • “The Philosopher [Aristotle] says [De Anima iii, 4] that things are intelligible in proportion as they are separate from matter. Therefore, material things must needs be understood according as they are abstracted from matter and from material images, namely, phantasms.” Summa, I, 85, i • As this quote indicates, Aquinas’ Theory of Abstraction is a development of Aristotle’s. • Recall that Aristotle maintained that external objects are substances and substances are composite realities. • Substances are the union of matter and form. • In reality, matter and form are never separated. • That is, in reality, one never finds form with matter, nor matter without form. • Within the human mind, however, the two can be separated. • How abstraction works: – In perception, by means of phantasms, humans come to know particular substances. – The mind then abstracts from the phantasms whatever is common to them. – “[T]he things which belong to the species [form] of a material thing – such as a stone, or a man, or a horse – can be thought of apart from the individualizing principle [matter] . . . . This is what we mean by abstracting the universal from the particular, or the intelligible species [form] from the phantasm; that is, by considering the nature of the species [form] apart from its individual qualities [matter] [perceived by means of] the phantasms” Summa, I, 85, i – “‘Appleness’ exists only in individual apples. But, the intellect can abstract, or focus, on the form alone without the matter; thus, the form as known is universal (for matter is what individuates form). Universality is in the mind, not in the world.” Peter Kreeft, Footnote 89 in Summa of the Summa, p. 327 • It is by means of his Theory of Abstraction, that Aquinas avoids Hume’s skepticism. – Since abstraction “enhances” perception, humans can truly know universal natures. – By examining universal natures, humans can come to know how these natures necessarily relate to one another. – As a result, the Principle of Universal Causation is based on more than just the constant conjunction of particular events. – It is based upon the necessary relationships that exist between universal natures. – For example, given its nature, when a marker is dropped within a gravitational field strong enough, it will fall toward the center of that field. – Thus, given both the nature of the marker and the nature of gravity, gravity necessarily causes the pointer to fall. • Final Thoughts – By rooting his analysis of human knowledge in common sense, Aquinas avoids both Hume’s radical skepticism and PostModernism. – Although it is rooted in common sense, Aquinas’ analysis goes far beyond it. Thus, it is truly philosophical. – What else should be expected from a Philosopher of Common Sense?