Introduction to Experimental Psychology module III 2009

advertisement

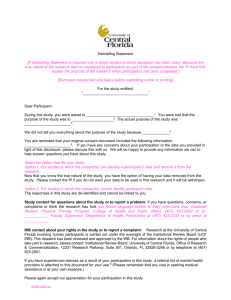

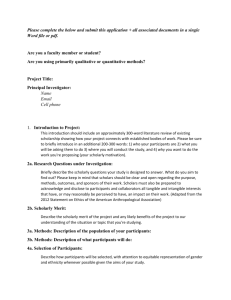

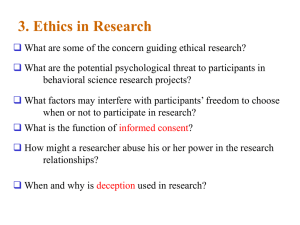

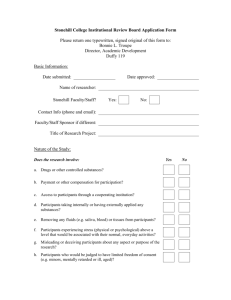

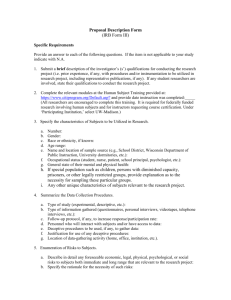

Chapter 11: Quasi-Experimentation Quasi-Experimentation—experimental manipulations in which the experimenter does not manipulate variables as in a typical laboratory experiment (Reichart & Mark, 1998) In a quasi-experiment, some or all of the variables are selected, which means that they are not under the direct control of the experimenter There are natural “treatments” such as disasters that can be observed but not manipulated Also, subjects cannot be randomly assigned to IV levels when you have subject variables because a person’s status on these variables is fixed E.g., age, sex, race, gender, weight, height, IQ Chapter 11 continued: Threats to Internal Validity in quasi-experiments: For observation-treatment-observation designs, there is no true reversal because the treatment is not under the experimenter’s control because of carryover effects and changes in the participants, themselves Maturation—changes in people over time because of growth or other historical variables History/Period effects—important historical effects/events that can affect subjects (e.g., wars, 9/11/01, the depression) E.g., cognitive development These are assumed to affect everyone that lives through these Birth Cohorts—specific events that occur during specific times of people’s lives (e.g., the depression) that make this cohort different than others These are generation-specific—a child had different experiences in the depression than did an adults Chapter 11 continued: To overcome threats to internal validity for natural treatments, we can use: Nonequivalent control groups—a control group that is not determined by random assignment but is usually selected after the fact and is supposed to be equivalent to the naturally treated group For example, if we were looking at a new third-grade reading curriculum (ABA), we could compare this class ex post factor with another third grade class that was similar to the one we studied but did not receive the new curriculum Because we did not randomly assign subjects to groups, though, we could have induced selection bias Chapter 11 continued: To overcome threats to internal validity for one-shot case studies (AB design), we can use: Deviant-case analyses—when we take an individual as similar as possible to our case except for a crucial missing treatment and then determine how the individuals are different from each other The similar individual is a nonequivalent control because the case was selected and not randomly assigned to the “control” condition The best the researcher can hope for from this design is to search for potential causal variable P.Z. was a famous scientist who abused alcohol and had a severe memory loss Butters and Cermak (1986) compared him to a colleague of similar age and background except the colleague did not drink Because the colleague did not show severe memory deficits, the researchers concluded that P.Z.’s memory loss was due to his heavy drinking Chapter 11 continued: One-shot quasi-experiments can also be useful in providing descriptive information and, perhaps, even causal; information In the Munich airport study, researchers looked at two experimental groups of children—one who already had been exposed to airport noise at an old airport, and another who was about to be at a new airport Two control groups were not exposed to airport noise Wave 1 was 6 months before the opening of the new airport, Wave 2 was one year later, and Wave 3 was two years later The results showed that memory improved after the noise was removed Chapter 11 continued: Threats to validity in time series studies Interrupted times series design—when you have an experimental group that you follow over time (before and after a naturally occurring treatment) E.g., the relation between school achievement and introduction of fluoride into drinking water—school achievement increased after fluoride was introduced However, you need to control for other possible IVs (e.g., better health care, better food, more time spent on school) You can use nonequivalent controls and multiple dependent variables to increase validity Chapter 11 continued: Designs employing subject variables: age as a variable—is it due to maturation, history, or cohorts? Cross-sectional Longitudinal Regression to the mean, selective attrition Time-lag—look at the effect of time of testing while holding age constant (cohort is confounded with time of testing) Cross-sequential—testing two or more age groups at two or more times (age is confounded) Cohort-sequential-- Chapter 12: Conducting Ethical Research Research—Applied to ethics is a class of activities designed to develop or contribute to generalizable knowledge (Levine, 1986) The Belmont Report (1979) formed the foundation of research ethics in the US—it has three core components: Respect for Persons—this resulted in a requirement in most situations that research participants consent to participate (informed consent) this typically requires: Beneficence—this is the idea that researchers need to justify their research benefits in the context of their costs/risks Disclosure of risks by researchers Understanding of the study by participants Voluntariness of participants (e.g., you cannot force a person to participate in medical research or face a loss of care) Competence—the participant needs the ability to make informed consent (e.g., severe dementia) All research should involve a cost (or risk)/benefit analysis Justice—this is the idea that society, in general, should not only benefit in research equally, they should participate in it equally E.g., in is inappropriate to force prisoners, institutionalized children, and economically impoverished individuals to participate in risky research Chapter 12: Ethics Continued: Research with human subjects: APA’s 10 principles: during the planning stage of a study, the investigator has the responsibility to make a careful evaluation of its acceptability. This should involve a “cost-benefit analysis” Determine whether subjects will be “at risk” or at “minimal risk” The principal investigator holds primary responsibility—even for collaborators and other employees or assistants. Except when approved by an IRB (institutional review board), it is required that subjects read and sign a consent form in which they agree to participate after being informed of the procedures. When deception is necessary (and is justified after a cost-benefit analysis), it is important to debrief subjects afterwards (except in rare circumstances when such debriefing would only hurt the subjects— although this determination must be made by the IRB—not the investigator). Chapter 12: Ethics continued Research with human subjects: APA’s 10 principles continued: Subjects have the right to decline participation without being penalized. This includes ending participation partially through the experiment. Protection from harm—risk is minimalized, and participants should be informed of how to contact the investigator if they have any questions or concerns at a later time. Also, subjects need to be informed of an IRB contact in case they questions about their rights as a research subject. Subjects should be debriefed after completing the study. If debriefing is not the best option as determined by the IRB, it is still the experimenter’s responsibility to protect the subject from long-term negative consequences. Research results obtained from a given subject are anonymous or confidential unless otherwise agreed upon before participation. Typically results are reported in group form, or in a case study, names are changed to protect the true identity of the subject (e.g., H.M.). Anonymous—when there is no link between the data and the identity of a subject (this includes linklists) Confidential—when the experimenter knows the identity of the subjects, but keeps this information secret from all non-qualified personnel Chapter 12 continued: Key components of ethical issues with human subjects: Informed consent Deception and debriefing Freedom to withdraw from research without penalty Protection from harm Debriefing, in general Removing harmful consequences (e.g., following up on subjects) Confidentiality or anonymity Chapter 12 continued: Examples: Milgram and obedience to authority Watson and Little Albert (conditioned fear and failure to remove harmful consequences) Zimbardo and post-hypnotic suggestion (again, failure to debrief) The Tuskegee Syphilis study (no justifiable rationale—this one fails all three Belmont Criteria) Alzheimer’s research and informed consent Genetic testing research and HIPA Cloning Psychologists participating in torture-like interventions Chapter 12 continued: Ethics in Animal research arguments against animal research by animal rights activists: animals feel pain destroying or harming any living thing is dehumanizing the human scientist claims about scientific progress being helped by animal research are a form of racism speciesism—neglecting the rights and interests of other species arguments in favor of research with animals (most experimental psychologists disagree with the last three conclusions) while animals feel pain, a cost-benefit analysis must be carried out and approved before animals can be put into painful conditions given that humans are primarily carnivores, this second point is difficult. Again, a costbenefit analysis must be carried out before any animal can be hurt. With regard to speciesism, much animal research actually helps animals. However, a certain level of speciesism is probably necessary unless humans are willing to have a higher death rate from many diseases. Chapter 12 continued: Guidelines for use of animals in research: The acquisition, care, use, and disposal of all animals must be in compliance with the current federal, state or provincial, and local laws and regulations (e.g., air circulation and temperature regulation) A psychologist in charge must be qualified to carry out the research methods and oversee the care of laboratory animals. The psychologist in charge is responsible to ensure that all project personnel have instruction in experimental methods, and in the care, maintenance, and handling of the species being used. Psychologists take every effort to minimize discomfort, illness, and pain of animals. Subjecting animals to pain, stress, or deprivation is used only after cost-benefit analysis justification. Surgical procedures are performed under appropriate anesthesia, and techniques to avoid infection and minimize pain are followed during and after surgery. When it is necessary to terminate an animal’s life, it should be done rapidly and painlessly. Chapter 12 continued: Scientific fraud: deliberate bias by scientists falsification—reporting incorrect data that have been collected fabrication—making up uncollected data plagiarism—using others’ work as your own and not attributing this work to others idea plagiarism—stealing another person’s idea without giving them credit (can be unconscious) intellectual property Chapter 13: Interpreting the Results of Research: Interpreting specific results: Scale attenuation—when performance exceeds the limitations of the measurement scale (ceiling or floor effects) To fix scale attenuation, we can add other dependent variables (e.g., RT to the memory study), or we can examine data points that do not exhibit scale attenuation—e.g., 3, 6, and 9 seconds of retention interval in the Scarborough (1972) study. Regression artifact (regression toward the mean)—the tendency for extreme measures on some variable to be closer to the group mean when re-measured, due to unreliability of measure. A large change in performance due to regression to the mean does not mean that true-score performance has changed, but, rather, that you have measurement error that inflated or deflated some scores. random assignment to different conditions helps minimize regression toward the mean because it equates your groups efficiently as long as your sample is sufficiently large. Chapter 13 continued: Interpreting patterns of research: reliability and replication test reliability—is your test consistent? Experimental reliability—the ability to replicate your results Chapter 13 continued: three types of replications: direct, systematic, and conceptual direct replication: simply repeating an experiment as closely as possible with as few changes as possible in the methods. systematic replication: repeating an experiment while varying numerous factors considered to be irrelevant to the phenomenon to see if it will survive these changes. Conceptual replication—attempting to demonstrate an experimental phenomenon with an entirely new paradigm or set of experimental conditions. Chapter 13 continued: Converging operations—procedures that validate a hypothetical construct used to explain behavior by eliminating alternative explanations (Garner, Hake, & Eriksen, 1956. use Allen, Sliwinski, and Bowie (2002) as an example—do older adults have consistent peripheral deficits for semantic and episodic memory (compared to younger adults), but no deficit for semantic slopes and a large deficit for episodic slopes? Chapter 14: Presenting Research Results: How to write a research report: develop an outline use APA format: title page, abstract, introduction, method, results, discussion, references, author notes, tables, figure captions, figures Chapter 14 continued: It is important to remember that writing a paper is also a compromise between achieving scientific precision and expressing creativity. Also, you will be faced with the dilemma of precision versus parsimony. Writing is a craft that takes practice. Most journal submissions take many drafts before they are ready for submission. It helps to have at least one other person read your paper and to provide you with comments before you submit it. Chapter 14 continued: In the Introduction, the toughest portion of a paper to write, you state why a particular issue is of interest, what other investigators have found, and what variables you will be examining, and how this will extend previous knowledge. You should review relevant research that helps you set up your own research question. At the end of your Intro, you should provide an overview of your new experiment(s). Specify your hypotheses explicitly and outline your predictions derived from the theories that you have already discussed. After reading your Introduction, it should be clear how your new work is extending our knowledge in a given area or areas. Chapter 14 continued: How to publish an article in a peer-reviewed journal: submit several copies via mail or electronically submit an article (e.g., using a PDF format) Your article will be sent out to review by the journal editor (or associate editor that serves as the action editor on your manuscript). Usually your manuscript will be sent to 2-4 outside reviewers. This is termed peer review. The reviewers will evaluate your paper on the basis of its scientific merit. When the editor receives the reviews back, then he or she must decide whether to reject without a request for resubmission, request a revision, or accept your manuscript. Keep in mind that rejection is the norm. Chapter 14 continued: Publishing Continued: If your paper is rejected, you take the comments from the reviewers and the editor into consideration in the revision process. It frequently will require additional data collection to fix problems brought up by the reviewers. Once you have addressed these concerns, you typically will submit your revised paper to another journal—until you find a journal that finally accepts your paper. It is common for psychology professors to go through their entire career and obtain 20 peer-reviewed publications, or less. So, this is a grueling process that requires a lot of patience and perseverance. Chapter 14 continued: Publishing continued: Once your paper is accepted for publication (you will receive a letter from the journal editor informing you of this considerable accomplishment), you still will have at least the galley proof stage of revision (and maybe a copy edit version before the galley proof stage—this is the case for most APA publications). After a paper has been accepted for publication, there is usually a 6-month to 2-year lag before the paper actually appears in print in the journal. All told, the publication process from initial submission to the appearance of a paper in print is usually 2-3 years (although your professor is, hopefully, just completing one project that has been ongoing for 10 years!).