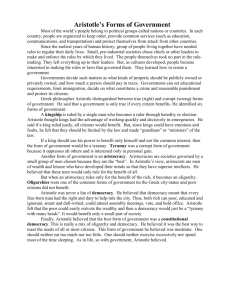

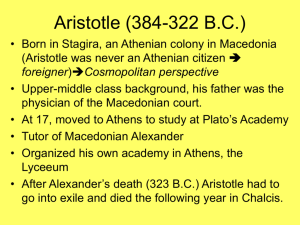

AristotlePol.4.010

advertisement

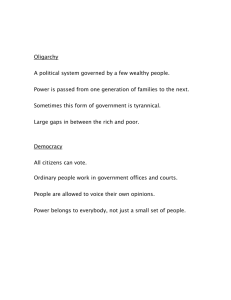

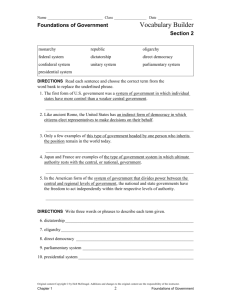

Aristotle: Politics.4 bk. IV [1] • • subject of Bk IV: “the best form of government” Aristotle distinguishes: • (1) what is best in the abstract • • • • • (2) best relatively to circumstances [what is this contrast??] (3) how formed, how longest preserved [these may seem two different things, but see next...] (4) what is best suited to states in general Aristotle: Politics.4 bk. IV [2] • “the best form of government” • “We should consider, not only what form of government is best, but also what is possible and what is easily attainable by all.” • Any change of government should be one which men, starting from their existing constitutions, will be both willing and able to adopt • there is quite as much trouble in the reformation of an old constitution as in the establishment of a new one, just as to unlearn is as hard as to learn. • the statesman should be able to find remedies for the defects of existing constitutions, as has been said before. • This he cannot do unless he knows how many forms of government there are. Aristotle: Politics.4 bks. IV [3] • • • • • • The division of one, few, many, is inadequate: there are many forms of democracy and of oligarchy which laws are best depends on the constitution “laws are not to be confounded with the principles of the constitution” we’ll describe the other forms too: tyranny, oligarchy, and democracy. “the perversion of the first [monarchy] and most divine is necessarily the worst.” (A. says this is “obvious”) • [presumably the idea is that he who can do the most good can also do the most harm.] • [which brings up the thought that a high-priority constitutional task would be, how to prevent this perversion...] Aristotle: Politics.4 bks. IV [4] • • • [Plato says that democracy is the best of the bad constitutions, but the worst of the good ... Aristotle says “whereas we maintain that they are in any case defective, and that one oligarchy is not to be accounted better than another, but only less bad.” - Is this a “distinction without a difference”??] • A more fundamental question: what is a constitution? • [saying, “the basic structure of the political system” is only mediumhelpful - what is “basicness” for this purpose?] • [we nowadays sometimes have written constitutions. Why?] • [Aristotle is obviously not talking about those. • But what he is talking about could have been written up. • Would that have been a good idea?] Aristotle: Politics.4 bks. IV [5] • • • • • • • • • • • • • • Tasks: In his study of constitutions, A. will investigate - their varieties - what is the “most generally acceptable,” - how a constitution is suitable to a given populace, - how a reformer should proceed, and -“the modes of ruin and preservation” of “constitutions generally and of each separately” Why are there different forms? differences in the wealth of various families; how they make their livings; etc In short: the wholes are different because the parts are... “Generally thought to be” just one each of two principal forms: aristocracy: “really a kind of oligarchy” constitutional: really a kind of democracy says the first are “true”, the second “perversions” and, the “better way” to study them is via the true forms Aristotle: Politics.4 bks. IV [6] • • • • • • • Democracy and Oligarchy - more precisely defined ... “It must not be assumed, as some are fond of saying, that democracy is simply that form of government in which the greater number are sovereign, for in oligarchies, and indeed in every government, the majority rules; nor again is oligarchy that form of government in which a few are sovereign.” [In what sense does “the majority rule in every government??] It is only an “accident” that most are poor suppose most were rich, and excluded the rest from power - “no one would say that this is a democracy” Or if the few poor took control, excluding the rich, you wouldn’t have oligarchy “But the form of government is a democracy when the free, who are also poor and the majority, govern, and an oligarchy when the rich and the noble govern, they being at the same time few in number. Aristotle: Politics Bk IV • • • • • • • • • • • • • [7] ... [S]tates are composed, not of one, but of many elements: 1) food-producing class, who are called husbandmen 2) mechanics who practice the arts without which a city cannot exist.... 3) traders, who are engaged in buying and selling. 4) serfs or laborers 5) warriors (“ as necessary as any of the others, if the country is not to be the slave of every invader”) [“The state is independent and self-sufficing - a slave is the reverse Note: Aristotle assumes that militarily weak states will routinely be conquered by outsiders.... Peace doesn’t seem to be the default assumption.. ] 6) “military class” [distinct from “warriors” evidently? - includes generals?] 7) “the wealthy who minister to the state with their property” 8) “magistrates and officers” 9?) “judges”: those who deliberate and who judge between disputants Aristotle: Politics Bk IV • • • • • • • • • [8] How far do we take our division of “classes”? “both in the common people and in the notables various classes are included; commoners: husbandmen, artisans, traders, seafarers (some engaged in war, others in trade, as ferrymen or as fishermen.) ... day-laborers ... and there may be other classes as well. The notables again may be divided according to their wealth, birth, virtue, education, and similar differences.” Democracy: (1) “based strictly on equality” [n such a democracy the law says that it is just for the poor to have no more advantage than the rich - neither should be masters, but both equal.] For if liberty and equality are chiefly to be found in democracy, they will be best attained when all persons alike share in the government to the utmost. And since the people are the majority, and the opinion of the majority is decisive, such a government must necessarily be a democracy. Aristotle: Politics IV • • [9] • • Democracy: (2) another, in which the magistrates are elected according to a certain property qualification, but a low one (3) all who are “under no disqualification” share in govt “but the law is supreme” (4) every citizen admitted, but law still supreme (5) not the law, but the multitude, have the supreme power, and supersede the law by their decrees [(5) is due to “demagoguery” [H. L. Mencken defined a demagogue as "one who preaches doctrines he knows to be untrue to • [A.: For • • • • • men he knows to be idiots.”] in democracies which are subject to the law the best citizens hold the first place, and there are no demagogues; but where the laws are not supreme, there demagogues spring up.” [JN adds: here Aristotle appears to be working on the modern idea of constitutional democracy: democracy with constitutional restraints on what the “mob” (i.e. majority) can do....] Aristotle: Politics IV • • • • • • • • • • [10] Democracy (continued): “For the people becomes a monarch, and is many in one; and the many have the power in their hands, not as individuals, but collectively. this sort of democracy, grows into a despot; the flatterer is held in honor; this sort of democracy being relatively to other democracies what tyranny is to other forms of monarchy. “those who have any complaint to bring against the magistrates say, 'Let the people be judges'; the people are too happy to accept the invitation; and so the authority of every office is undermined.” The spirit of both is the same, and they alike exercise a despotic rule over the better citizens. “the system in which all things are regulated by decrees is clearly not even a democracy in the true sense of the word, for decrees relate only to particulars.” [‘decree’ - arbitrary and particular; ‘law’ is general (and supposedly reasonable)] it is “open to the objection that it is not a constitution at all” [very prescient!] Aristotle: Politics IV [11] • Oligarchies • • • (1) where the poor have no share in govt (2) high qualification for office - If the election is made out of all the qualified persons, a constitution of this kind inclines to an aristocracy, if out of a privileged class, to an oligarchy. (3) if the son succeeds the father, it’s a hereditary oligarchy (4) If in a hereditary oligarchy the “magistrates are supreme and not the law” we have oligarchic tyranny [becomes a dynasty] [A. notes: in many states the constitution which is established by law, although not democratic, owing to the education and habits of the people may be administered democratically] conversely in other states the established constitution may incline to democracy, but may be administered in an oligarchical spirit. This most often happens after a revolution: old laws are administered in a new spirit, as the revolutionaries have the power to interpret and apply them ... • • • • • • Aristotle: Politics IV • • • • • • • • • [12] Other forms: (5) true aristocracy: “government formed of the best men absolutely, and not merely of men who are good when tried by any given standard. In the perfect state the good man is absolutely the same as the good citizen;” [Q: why count this a fifth form? Isn’t it just the first form when it’s working well??] Polity and [last and least] Tyranny Polity: Polity = constitutional government may be described generally as a fusion of oligarchy and democracy but the term is usually applied to those forms of government which incline towards democracy, and the term aristocracy to those which incline towards oligarchy, because birth and education are commonly the accompaniments of wealth. Moreover, the rich already possess the external advantages the want of which is a temptation to crime, and hence they are called noblemen and gentlemen. And inasmuch as aristocracy seeks to give predominance to the best of the citizens, people say also of oligarchies that they are composed of noblemen and gentlemen. Now it appears to be an impossible thing that the state which is governed not by the best citizens but by the worst should be well-governed, and equally impossible that the state which is ill-governed should be governed by the best. [Is that so??] Aristotle: Politics IV [13] • Citizen Compliance: • • • • good laws, if they are not obeyed, do not constitute good government Hence there are two parts of good government; one is the actual obedience of citizens to the laws, the other part is the goodness of the laws which they obey; they may obey bad laws as well as good. a further subdivision: they may obey (1) the best laws which are attainable to them, or (2) the best absolutely [JN asks: Why make this distinction? -[- because there is almost always an element of compromise in politics e.g. we can go along with L because although L1 would be better, yet if few do L1 and all do L, the results may be better...] • • • • • • Aristotle: Politics IV [14] • further on polity: • The distribution of offices according to merit is a special characteristic of aristocracy, for the principle of an aristocracy is virtue, as wealth is of an oligarchy, and freedom of a democracy. [JN: are we taking these as definitions, or not? ... [And re “freedom”: A. will later make an important distinction, which makes it dubious to identify democracy generally with freedom...] rich and poor: three grounds on which men claim an equal share in the government: freedom, wealth, and virtue good birth is the result of the two last, being only ancient wealth and virtue) Polity is the admixture of the rich and poor [“true union of oligarchy and • • • • • • • democracy when the same state may be termed either...] • • • Aristocracy is the union of the three - or, government of the best “more than any other form of government, except the true and ideal, has a right to this name. Thus, polities and aristocracies are, plainly, not very unlike. Aristotle: Politics IV [15] • Tyrannies • • • • • • • • • • elected monarchies (as among the “barbarians”) (1) “royal”: the elected monarchs rule according to law over willing subjects (2) despotic: when they rule according to their own fancy (3) tyrannical: arbitrary power of an individual responsible to no one governs all alike, whether equals or better, with a view to its own advantage, not to that of its subjects, and therefore against their will. [i.e. Thrasymachean] “No freeman, if he can escape from it, will endure such a government.” [q: what’s the difference between (2) and (3)? tentative answer: T(2) rules by arbitrary schemes but not out of sheer selfinterest; T(3) rules strictly to enrich himself] - an importance difference [Castro might be (2); Mugabe, (3). Note: but Castro’s wealth has been estimated at near $1 billion (!)] Aristotle: Politics IV [16] • “Best Constitution for Most States” • • • • • • • • • • • • adds: and the best life for most men neither assuming a standard of virtue which is above ordinary persons nor an education which is exceptionally favored by nature and circumstances, nor yet an ideal state which is an aspiration only but having regard to the life in which the majority are able to share and to the form of government which states in general can attain... “if [his] Ethics is true - that a) the happy life is the life according to virtue lived without impediment, b) and that virtue is a mean ... -> (c) the life which is in a mean, and in a mean attainable by every one, must be the best. [question: is this a ‘mean’ in the same sense as in the Ethics?] And the same principles of virtue and vice are characteristic of cities and of constitutions; for the constitution is in a figure the life of the city. Aristotle: Politics IV [17] • • “Best Constitution for Most States” Government for the Middle .... • all states have some rich, some poor, and some between • so: moderation • • • • • • • • and the mean are best therefore it will clearly be best to possess the gifts of fortune in moderation; for in that condition of life men are most ready to follow rational principle [really?? - interesting! - what about geniuses??] “But he (1) who greatly excels in beauty, strength, birth, or wealth, or on the other hand (2) who is very poor, very weak, or very much disgraced, -> finds it difficult to follow rational principle. type 1 - grow into violent and great criminals type 2 - into rogues and petty rascals again: those who have too much of the goods of fortune, strength, wealth, friends, and the like, are neither willing nor able to submit to authority Aristotle: Politics IV [18] • “Best Constitution for Most States” • “But a city ought to be composed, as far as possible, of equals and similars; and these are generally the middle classes. Wherefore the city of middle-class citizens is necessarily best constituted in respect of the elements of which we say the fabric of the state naturally consists. • • Thus it is manifest that the best political community is formed by citizens of the middle class, • and that those states are likely to be well-administered in which the middle class is large, and stronger if possible than both the other classes [or at least, than either taken singly] • “The mean condition of states is clearly best, for no other is free from • faction; and where the middle class is large, there are least likely to be factions and dissensions” [note: thus, Harmony!] Aristotle: Politics IV [19] • • • • • • • • • • • • Problems : alas: the poor and the rich quarrel with one another whichever side gets the better, instead of establishing a just or popular government, regards political supremacy as the prize of victory [“to the victor belongs the spoils”!] and the one party sets up a democracy and the other an oligarchy. For these reasons the middle form of government has rarely, if ever, existed, and among a very few only: On Aristocracy: those who desire to form aristocratical governments often make a mistake: not only in giving too much power to the rich but in attempting to overreach the people There comes a time when out of a false good there arises a true evil, since the encroachments of the rich are more destructive to the constitution than those of the people. Aristotle: Politics IV [20] • • • • • • • • • • Problems of Oligarchies: Assembly attendance: rich fined for nonattendance, poor not It is obvious that he who would duly mix the two principles should combine the practice of both, and provide that the poor should be paid to attend, and the rich fined if they do not attend, for then all will take part; if there is no such combination, power will be in the hands of one party only. The government should be confined to those who carry arms [note: arms at the time were very expensive] As to the property qualification, no absolute rule can be laid down but we must see what is the highest qualification sufficiently comprehensive to secure that the number of those who have the rights of citizens exceeds the number of those excluded. Even if they have no share in office, the poor, provided only that they are not outraged or deprived of their property, will be quiet enough. But to secure gentle treatment for the poor is not an easy thing, since a ruling class is not always humane. And in time of war the poor are apt to hesitate unless they are fed; when fed, they are willing enough to fight. Aristotle: Politics IV [21] • Division of elements: • • • • • (1) those who “deliberate about public affairs” [ = legislative] (2) magistrates [ = executive] (3) judicial Are the powers re (1) to be assigned to all the citizens, or only some? If some, which? [e.g., the rich, gives you oligarchy] • oligarchies: the veto of the majority should be final, their assent not final, but the proposal should be referred back to the magistrates. constitutional governments, the contrary : the few have the negative, not the affirmative power; the affirmation of everything rests with the multitude. [Is Aristotle speaking with approval of these arrangements?] (2) Which offices? How long is the term? The answer varies with • • • circumstances,e.g. big states will have more... • Aristotle: Politics IV [22] • Division of elements: • (3) judicial • • • (1) are the judges taken from all, or from some only? (2) how many kinds of law-courts are there? (3) are the judges chosen by vote or by lot? ... • democracy: judges selected by lot • oligarchy, a few do all • aristocratical - some courts from all classes, some from a few... • [end of Bk Four]