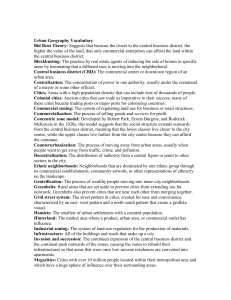

Urban Environmental Health

advertisement

Boston University School of Public Health Department of Environmental Health Course Title: The Built Environment: Design Solutions for Public Health Instructors: Russ Lopez, DSc, MCRP, Adjunct Assistant Professor Credits: 4 Meeting dates: Wednesday 6:00 – 8:45 September 2 – December 16 Course goals: This course will provide an overview of urban planning to public health students and introduce public health concepts to urban planners. At the conclusion of the course, students will be able to: - - Explain the rationale behind historical and current theories on the relationship between the built environment and public health Identify contemporary features of the built environment such as parks, public works projects, single family homes, apartment buildings, transportation systems and highways, etc., that reflect past efforts to influence health. Critique historic patterns of development and assess the health consequences of contemporary urban forms. Evaluate the evidence for the built environment–health link. Explain the role of the built environment in the context of other factors that influence health. Understand how the built environment might influence other efforts to protect and promote health. Utilize studies and methodologies developed by sociologists, anthropologists, urban planners and architects to evaluate the health impacts of the built environment. Propose built environment-based interventions, based on current evidence and the lessons learned from the past studies of the built environment, to promote public health. Develop and implement new programs and policies that utilize built environment and design to promote public health. Course Rationale This course provides students with an understanding of how the built environment impacts public health and the critical tools to evaluate specific design features. The modern urban planning and public health disciplines both had their beginnings over 100 years ago as reformers sought to address the problems associated with rapid urbanization, industrialization and immigration. Together, these reformers helped implement a wide variety of policies and programs including urban parks, water works and sewerage, zoning, and building codes. By the mid 20th century, however, advances in medicine, the emphasis on individual responsibility for disease and the professionalization of both disciplines resulted in a divergence of public health from planning. But at the end of the century, the persistence of risky health behaviors and the increase in obesity rates, particularly in the United States, prompted renewed attention to the link between built environment and health. The result has been a recent increase in connections between planning and public health. For example, the American Public Health Association now includes a Built Environment Institute at its annual meeting, and the American Planning Association holds training sessions on public health. This course places students at the intersection of this newly growing field. At the end of this class, students will be able to “read” the built environment, i.e., to identify elements whose design roots are based on solving specific health issues. These solutions have dramatically impacted the built environment and underpin the ways in which buildings, neighborhoods and cities are built today. As our understanding of public health has evolved over the past century, and as the unintended public health consequences of previous design solutions have become recognized, attempts to address public health through design have also evolved rapidly, and in ways which affect us every day. This course gives students a framework for evaluating historic, current and future design programs and policies. This framework is based on past epidemiologic, anthropological and economic studies of the built environment. Throughout this course, key studies are presented and the quality of the evidence is discussed. Course Overview The course is organized in a generally historical sequence, with overlaps in periods corresponding to overlaps in architectural and programmatic trends. All course readings will be available on the course website. Teaching method The course will consist of lectures and class discussions. Students are encouraged to draw on their own experiences—the neighborhoods they grew up in, the houses they live in now, how they access school and employment—and contribute these examples to class discussions. The goal is to encourage students not to take the contemporary built environment as immutable or purposeless, but instead be able to identify elements that reflect past concerns for health and assess current programs and policies in light of new understanding of the built environment – health connection. Course Requirements The written coursework will consist of four short assignments and a final paper. Assignment 1: Boston’s South End (Due Class 4 – September 23) Assignment 2: Neighborhood Audit Checklist (Due Class 7 - October 14) Assignment 3: London’s Congestion Charge (Due Class 10 - November 4) 2 Assignment 4: Urban Renewal in Mumbai (Due Class 13 – December 2) Assignments: These Assignments will be based on short handouts that will be made available on the Course Web Site. Two first two are observational and will require short walks (one through the South End, one in a neighborhood of your choice). The second two are policy focused. Each Assignment length should be 2 pages (double spaced, 12 point type, 1 inch margins), not including references (if any). Final Paper: The paper will be on a topic proposed by the student and approved by the course instructor. Topics can be any relevant public policy, theory or specific case example related to the built environment and public health. Papers should describe the policy, theory or case; identify how it represents an attempt to manipulate the built environment; connect it to other types of interventions or activities; critique it from the standpoint of health and suggest possible modifications that might strengthen it. Final paper length should be 10 pages (double spaced, 12 point type, 1 inch margins), not including references. Representative paper titles include: o Celebration, Florida: A health, equity and sustainability critique. o Smart growth and affordable housing: Do growth controls hurt the poor? o Mass transit vs. subsidies for automobile ownership: How to increase transportation options for the urban poor. Important paper deadlines are: Class 8: Paper topics due Class 11: Literature Review Due Class 14: Paper Due Class 14 and 15: Final presentations Grading Assignment 1: Boston’s South End 10% Assignment 2: Neighborhood Audit Checklist (10%) Assignment 3: London’s Congestion Charge 10% Assignment 4: Urban Renewal in Mumbai 10% Final Paper: 40% Final Presentation: 10% Class Participation: 10% 1. Introduction: Course overview and themes. Sept. 2 In this session, we cover the role of the built environment in health. We begin with a review of health, which is more than the absence of disease, and explore the concepts of association and causation, and the proximate and underlying factors affecting health. This overview stresses that the built environment is just one factor among many affecting health. It lays a foundation for assessing and understanding the various strands of evidence linking the built environment to health. We describe the issues to be covered during the course and place these issues into the 3 context of other forces affecting cities. We explain the differences and relationship between the health of cities, a complex of economic and social activity, and the health of individuals living in cities, whose health status reflects the influences of these activities on individual outcomes. There will also be a discussion of three frameworks for assessing the built environment: health, equity, and sustainability. Objectives: At the end of this session students should be able to: - Discuss the basic problems and advantages of cities; - Articulate and describe the historical and current trends of urbanization in the US and in the world; - Assess their own assumptions about cities and urban public health. Readings 2. Frumkin H. 2003. Healthy places: Exploring the evidence. American Journal of Public Health. 93(9):1451-6. Galea S, Freudenberg N, Vlahov D. 2005. Cities and population health. Social Science and Medicine. 60(5):1017-1033 Owen D. 2004. Green Manhattan. The New Yorker, 10/18/04. 19th Century: The Urban Health Crisis . Sept. 9 Cities in the Western world grew rapidly because of industrialization, immigration and urbanization. The results of the rapid growth of cities were large slums with substandard and dangerous housing, high levels of infectious diseases including tuberculosis, and overburdened roads and infrastructure. Between epidemics of cholera and rising levels of urban violence, it seemed that the very ideas of progress and modernity were at risk. At this time, wealthy and middle class people began to leave cities and modern attitudes toward urban living were formed. A lasting legacy is that cities continue to be seen to be unhealthy and dangerous places, leaving the United States with a deep bias toward suburban living. Objectives: At the end of this session students should be able to: - Describe the health and environmental characteristics of 19th century cities; - Connect these 19th century city characteristics to 21st century attitudes toward cities and urban residents, and explain how these attitudes continue to drive current social, health and environmental policies; - Describe the history of the early public health movement and its connections to urban problems; - Understand the connections between urban planning and public health and use this understanding to critique policies and programs in both disciplines. 4 Readings 3. Garb M. 2003. Health, morality and housing: the “tenement problem” in Chicago. American Journal of Public Health. 93(9):1420-1430 Peterson J. 1979. The impact of sanitary reform upon American urban planning, 1840 – 1990. Journal of Social History. 13(1):83-103 Wirth L. 1938. Urbanism as a way of life. Am J Sociology. 44(1)1-24 The age of reform. Sept 16 Public health advocates and social reformers found a connection between living in tenements and neighborhoods near large factors and communicable diseases such as tuberculosis and chronic diseases such as depression and disabilities. To counter these problems, a number of initiatives were developed including the sanitarian movement, the development of water treatment and sewerage, and the separation of land uses to protect workers from industrial air pollution. The culminations of the 19th century reform movement include the great urban park systems (New York City’s Central Park, Boston’s Emerald Necklace, etc.), new water supplies, and other important contributions to health and welfare. Objectives: At the end of this session students will be able to: - Identify contemporary built environment features in the Boston area and elsewhere which date back to attempts by planners and health officials to address 19th century concerns; - Articulate the health concerns being addressed by these development features, and evaluate the success of those attempts; - Use contemporary urban environmental characteristics to illustrate past efforts to improve social outcomes; - Critique past efforts to incorporate health into planning and development. Readings 4. Cutler D. Miller G. 2005. The role of public health improvements in health advances: The Twentieth-Century United States. Demography 42(1):1-22 Blodgett G. 1976. Frederick Law Olmsted as conservative reformer. The Journal of American History 62(4):869-889 The triumph of theory: Frank Lloyd Wright and Le Corbusier. Sept 23 5 These two architects have shaped much of the 20th Century’s architecture and urban form. Both sought to address the health problems and social failures of the early 20th Century city, but in very different realms. Wright conceived of “Broadacre City”, a community of single family houses set on one acre plots – a design that describes much of modern American suburbs. Le Corbusier developed radical new designs for center cities, at one time proposing to tear down the Right Bank of Paris and replace it with large skyscrapers set in parks. Both had ideas that represent orthodox design to this day. At the end of this session, students will be able to: - Describe the influences on architectural theory in the first half of the 20th century; Understand the role of health in creating Modern architecture; Identify current design elements dating back to Wright’s and Le Corbusier’s theories; Identify how health was conceptualized and addressed in these architect’s designs; Critique these design elements given our current concern regarding chronic diseases. Readings 5. Grabow S.1977. Frank Lloyd Wright and the American city: The Broadacre debate. Journal of the American Planning Association. 43(2):115-124 Wright FL. 1935. Broadacre City: A new community plan. Architectural Record Bauer-Wooster C. 1965. The social front of Modern Architecture in the 1930s. The Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 24(1):48-52 The suburbs mature: Zoning, building codes and environmental design. Sept 30 The 20th Century saw the professionalization of public health and urban planning. Much of the effort of reformers was centered on the standardization of building and design techniques. Zoning was typical. It arose out of a failure of English Common Law to adequately protect health and property values from nuisances. (It was also used to preserve racial and religious purity of neighborhoods – a practice the supreme court ultimately over-ruled). Over time, standard zoning codes were developed and enabling legislation, with minor modifications, were adapted in almost every part of the US. The result is that new development has tended to look the same everywhere. Though we now know there are fundamental flaws with Euclidean Zoning (named after the community which was involved in the suit that resulted in zoning was declared constitutional – Euclid OH), it was very successful in eliminating and reducing the health and environmental problems of the late 19th and early 20th century urban environment. Suburban development has changed over time and this class session will cover some of the later theories linking development form and health. At the end of this session, students will be able to: - Describe the health basis for zoning and building codes; Understand the vital role of public health in the development of these codes; Identify how these codes were developed and adopted; Understand the goals of these codes and the health and environmental issues they were addressing. 6 Readings 6. Schilling J, Linton LS. 2005. The public health roots of zoning: in search of active living's legal genealogy. Am J Prev Med. ;28(2 Suppl 2):96-104. McHarg I. 1964. The place of nature in the city of man. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 352(1):1-12 Malizia E. 2005. City and regional planning: a primer for public health officials. American Journal of Health Promotion 19(5):Supplement 1-13. Suburban Discontent (guest lecture: Tammy Vehige) Oct 7. Suburbs were populated, at least in part, by families desiring a healthier environment than was possible in inner cities. These desires were fueled at least in part by the very real problems of infectious disease, sanitation and pollution that afflicted cities prior to World War II. But while suburbs were at one time healthier, improvements in the urban environment have reduced the suburban health advantage. Now there are new concerns about the suburbs: suburban design may discourage physical activity and increase, they eat up large parts of the natural environment, promote higher energy use and may erode social capital. At the end of this session, students will be able to: - Describe the evidence linking suburban development and health; Assess the adequacy of suburban health research; Describe how the built environment is measured and assessed in health research; Outline some of the additional impacts of suburbanization. Readings 7. Frank L, Anderson M, Schmid T. 2004. Obesity relationships with community design, physical activity, and time spent in cars. Am JPrev Med. 27(7):87-96 Northridge ME, Sclar ED, Biswas P. 2003. Sorting out the connections between the built environment and health: a conceptual framework for navigating pathways and planning healthy cities. J Urban Health. 80(4):556-68. Lopez R. 2007. Neighborhood risk factors for obesity. Obesity 15(8):2111-2118 Transportation. Oct 14. Virtually all development in the United States since World War II has been heavily automobile dependent, and thus both highly resource intensive and, we argue, antagonistic to public health goals. An important consideration is that not everyone can drive. The elderly, people with disabilities and the young may not be able to drive, others may not be able to afford a car. Most alternatives to car-oriented development center on relatively dense urban areas in which transportation can be more efficient, and often, human powered. In this class we will discuss specific design solutions intended to improve public health, environmental impacts, and energy use. These include communities built to favor the pedestrian and bicyclist, as well as transitoriented development. Some specific local design features (traffic calming devices; pedestrian 7 and bike amenities) will be discussed. What are the specific goals of these interventions? How do they hope to realize these goals? How effective are various design elements in promoting physical activity? The passage by Congress of the Intermodal Surface Transportation Efficiency Act of 1991, and its subsequent reenactments, created new funding and political channels by which these types of development might be realized; we will give an overview and discuss some examples. Objectives: At the end of this session students should be able to: - Describe the essential components, economic and environmental advantages, and public health impacts of walkable and bikeable communities; - Assess the health impacts of transit-oriented developments; - Describe the impact of ISTEA (and other funding sources) on urban and suburban development. Propose new projects fundable under ISTEA which might promote health; - Propose specific health-promoting design changes to local communities. Readings Jacobsen, P. L. (2003). "Safety in numbers: more walkers and bicyclists, safer walking and bicycling." Inj Prev 3): 205-9. Novacco, Stokols, Milanessi L. 1990. Objective and subjective dimensions of travel impedance as determinates of community stress. Am J of Community Psychology. 18(2):231-257 8. Urban renewal and public housing: Afflicting the poor. Oct 21 Urban renewal had a tremendous impact on US cities, destroying hundreds of neighborhoods and displacing millions of people. These negative effects, along with a shift in government priorities, have resulted in new programs designed to revitalize inner cities. These projects include large sports and cultural facilities, loans to upper income households to purchase housing, and rebuilding of older public housing projects and downtown business districts. But do these programs have a more benign impact on the poor? To a certain extent these newer programs mimic older policies that sought to replace poor people with middle class or upper income households. But they also include steps to improve the economic status of existing residents as well. All of them have potentially large health and environmental impacts. Objectives: At the end of this session students will be able to: - Describe the impact of urban renewal on the urban poor and racial minorities; - Understand how urban renewal and public housing programs were developed and implemented; - Analyze contemporary urban policies from a health perspective; - Describe the past and current “tools” planners have used to change neighborhoods. Readings 8 Fullilove M, Green L, Fullilove R. Building momentum: An ethnographic study of innercity redevelopment. American Journal of Public Health. 1999. 89(6):840-845 Leventhal T Brooks-Gunn J. 2003. Moving to opportunity: an experimental study of neighborhood effects on mental health. Am J Public Health. 93(9):1576-1582 Bauer C. 1945. Good neighborhoods. American Academy of Political and Social Science. 292:104-115 Lopez R. 2009 Public health, the APHA, and urban renewal. Am J Public Health. 2009 Sep;99(9):1603-11 9. Urban Ecology (Guest Lecture: Steven Miller). Oct 28 A major focus in this course is on solutions to the health problems posed by the built environment. In the Boston area, the Livable Streets Alliance has been working on community and advocacy. Steve Miller, the founder of Livable Streets, will be presenting on the how the group was organized, its methods for working for change, and its current initiatives. Readings: - To be announced 10. Contemporary design and programs. Nov 4 Public health, architecture and planning have responded to current critiques on the health effects of orthodox development by developing a new set of tools. These hold the promise of promoting health in ways that address the chronic disease issues of our time. There are critics, however, and we will explore how well New Urbanism, LEED, and other programs are achieving the goals they have set for themselves. Objectives: At the end of this session, students will be able to: - Describe and critique some of the key attributes of New Urbanism and Smart Growth,; - Understand how architects and planners have responded to the perceived problems with traditional zoning. Assess the potential of newer proposals for application in different communities; - Critique proposals to modify the built environment from a capital and temporal perspective; - Assess New Urbanist and smart growth developments using traditional zoning/development frameworks of analysis. 9 Readings 11. Geller A. 2003. Smart growth: a prescription for livable cities. American Journal of Public Health. 93(9):1410-1415. Burton, E. (2000). "The compact city: Just or just compact? A preliminary analysis." Urban Studies 37(11): 1969-2001. Lund H. 2003. Testing the claims of new urbanism: local access, pedestrian travel, and neighboring behaviors. J American Planning Association. 69(4):414-429 Tools: Evidence based design and health impact assessment. Nov 11 A major critique of earlier efforts to promote health via built environment improvements has been that it was not based on solid epidemiological evidence. Nor did they adequately address the full range of health and social impacts that may arise from new projects. The past few years have seen the development of two new assessment ideas: evidence-based design and health impact assessment. These will be presented and critiqued in class. Objectives: At the end of this session students should be able to: - Describe methodologies for evidence-based design and health impact assessment; Understand the strengths and limits of these techniques; Interpret the results from these assessment tools. Readings Evidence-based design could help quality of care. Healthcare Research Quality Imrpv 11(8):92-94 Ulrich R. 1984. View through a window may influence recovery from surgery. Science. 224(4647) 420-421 Bhatia R. Protecting health using an environmental impact assessment: a case study of San Francisco land use decision making. Am J Public Health. 2007 Mar;97(3):406-13. Epub 2007 Jan 31.Click here to read Dannenberg et al. 2008. use of health impact assessment in the U.S.: 27 case studies, 1999-2007. Am J Prev Med. 34(3):241-256 12. The Developing World: Colonialism, Globalization and Urbanization. Nov 18 13. Campbell and Campbell. Emerging disease burdens and the poor in cities of the developing world. J Urban Health. 2007 May;84(3 Suppl 1):54-64 Wei Y. Urban policy, economic policy, and the growth of large cities in China. Habitat International 1994 18(4):53-65. The Developing World: Infrastructure, Land Tenure and Other Contemporary Dec 2 10 To a certain extent, many of the problems confronting rapidly growing urban areas in the developing world today have parallels in the problems that US and European cities had to address 100 years ago including housing quality, infrastructure improvements, clean water and sanitation. But many of the issues are different including problems with land tenure, greenhouse gas emissions and global transport of capital and people. Some areas are not only successfully overcoming these challenges, but they may also be providing models for how older Western cities might adapt and change to a new global environment. Objectives: At the end of these sessions students should be able to: - Describe the social/economic constraints operating on 21st Century developing cities; Critique contemporary urbanization models from the course’s sustainability, equity, health framework; Propose and evaluate alternative infrastructure scenarios for developing world cities. Bai X, Imura H. 2000. A comparative study of urban environment in East Asia: Stage model of urban environmental evolution. International Review for Environmental Strategies. 1(1):135-158 Harris N. 1995. Bombay in a global economy: structural adjustments and the role of cities. Cities 13(3):175-184 14. Final paper presentations Dec 9 15. Final paper presentations Dec 16 Final papers will be due during this session. Objectives: The goal of the class project is to provide students with experience in applying theory learned in previous classes to built and proposed projects in urban design, urban planning, or transportation planning, with an eye to the affects of the project on public health. With the lessons and techniques learned in this class, how might these projects affect health? Are they sustainable? Do they represent an attempt to remediate the impacts of the built environment or do they represent a repeat of past mistakes? Readings: none A NOTE ON PLAGIARISM Plagiarism, including the copying of any work in whole or in part without citation, is an extremely serious offense and will not be tolerated. It violates the trust between students and 11 faculty, renders ineffective the pedagogical activities of the class and deprives students of the learning experience derived from course requirements. Violation of plagiarism guidelines will be treated severely and reported to the school for further action. 12