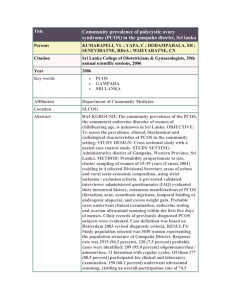

polycystic ovary syndrome in adolescents

advertisement

DR. Nedaa Bahkali 2012 Introduction Definition, DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA DIAGNOSTIC APPROACH Treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome in adolescents SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS Menstrual cycles are often irregular in the first months after menarche. According to a study by WHO : the median length of the first cycle after menarche was 34 days, with 38%of the cycles > 40 days and 7 % occurring <20 days apart . World Health Organization multicenter study on menstrual and ovulatory patterns in adolescent girls, J Adolesc Health Care. 1986 Menstrual disorders and abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) are among the most frequent gynecologic complaints of adolescents account for 50% . Menstrual disorders in adolescence: pathophysiology and treatment, Horm Res., 1991,Belgique. Menstrual disorders during adolescence, Pediatr Endocrinol Rev. 2006, University of Athens, Greece. Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) accounts for the vast majority of anovulatory symptoms and hyperandrogenism in adolescent . PCOS is the most common endocrine abnormality of reproductive-aged women in the United States. The The prevalence and features of the polycystic ovary syndrome in an unselected population, The University of Alabama at Birmingham, J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004. diagnosis of PCOS has life-long implications with increased risk for infertility, metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and probably cardiovascular disease. The classic syndrome originally was described by Stein and Leventhal as the association of amenorrhea with polycystic ovaries, and variably, hirsutism and obesity. J Obstet Gynecol 1935 Cutaneous hyperandr ogenism Obesity and insulin resistance PCOS Polycystic ovary Menstrual irregularity controversy arises from the fact that a polycystic ovary is often a normal variant and some asymptomatic ovulatory girls have subclinical PCOS according to the RotterdamAES criteria . None of these criteria fully addresses some of the unique problems in diagnosing PCOS in adolescents. As an example, even in girls without PCOS, approximately one-half of menstrual cycles are anovulatory in the first two years after menarche . Hyperandrogenism during puberty and adolescence, and its relationship to reproductive function in the adult female. In: Reproductive Medicine, Raven Press, 1993. Furthermore, polycystic ovaries may be missed by the Transabdominal ultrasound technique that is typically used for virginal adolescents, particularly if they are obese. Evaluation for PCOS is recommended in the following clinical scenarios: Girls with a sole finding of moderate or severe hirsutism, or a hirsutism equivalent, including persistent acne , or pattern alopecia Girls with mild hirsutism or obesity with any other feature of PCOS (eg, menstrual abnormality) Adolescent girls with menstrual irregularity that persists more than two years or who have severe dysfunctional uterine bleeding Adolescent girls with intractable obesity whether or not hirsutism, hirsutism equivalents, or menstrual irregularity are present DIAGNOSTIC APPROACH unexplained clinical and/or biochemical hyperandrogenism ovarian dysfunction Evidence of Hyperandrogenism Menstrual irregularity constitutes evidence of ovarian dysfunction. However, normal menstrual regularity does not mean ovulatory function is normal. A polycystic ovary is considered evidence of ovarian dysfunction in the setting of hyperandrogenism when menses are regular. The key androgen to measure is serum (or plasma) testosterone. Serum total and free testosterone: best assessed in the early morning. on days 4 through 10 of the menstrual cycle in regularly cycling women; norms are standardized for this part of the menstrual cycle. Oral contraceptive pills interfere with the assessment of androgens. They suppress gonadotropins, elevate sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG), and directly inhibit steroidogenic enzymes such as 3ß-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase. After discontinuing oral contraceptive pills, normal women may transiently have a slightly high total testosterone level but a normal free testosterone level because SHBG turnover is slower than testosterone turnover. Clinical practice. Hirsutism, N Engl J Med. 2005, Department of Pediatrics and Medicine, University of Chicago, USA. Total testosterone : The normal upper limit for serum total testosterone in women is approximately 60 ng/dl (2.0 nmol/L) . Free testosterone : An elevation in serum (or plasma) free testosterone is the single most sensitive test to establish the presence of hyperandrogenemia. The serum free testosterone concentration is about 50 percent more sensitive for the detection of hyperandrogenemia than the total testosterone concentration. This is because elevated insulin levels (a frequent concomitant of PCOS) and elevated androgen levels both act to inhibit hepatic production of sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG), which is the main determinant of the bioactive portion of serum testosterone, the fraction that is free or "bioavailable" the latter including the fraction that is loosely bound to albumin. International consensus criteria define a polycystic ovary on the basis of either excessive size or follicle number (or both), in the absence of a dominant-size follicle (>1.0 cc) or a corpus luteum. Using these criteria, a polycystic ovary can be identified by ultrasonography in about 75 % of women with PCOS. Excessive ovarian size is defined as an ovary with a volume >10.5 mL in adults >10.8 mL in adolescents. An alternate measure of increased volume is a maximal area >5.5 cm2. Most polycystic ovaries in PCOS are enlarged. Excessive follicle number is defined by vaginal ultrasonography as a total follicle count of ≥12 per ovary. In adolescents in whom abdominal rather than vaginal ultrasonography is indicated, it is defined as ≥10 follicles per maximum plane . These follicles are typically 2 to 9 mm in diameter. Asymptomatic volunteers with a polycystic ovary are a functionally distinct but heterogeneous population, J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009, Section of Adult and Pediatric Endocrinology, The University of Chicago , USA. The transabdominal ultrasonographic approach that is standard and appropriate in virginal adolescents may underestimate the prevalence of polycystic ovaries in comparison with the transvaginal approach used in adult women . This difference is modest. In a prospective study of patients with PCOS in which these criteria were used , a polycystic ovary was found in 69 percent of adolescents and 87 percent of adults (p = 0.12, unpublished data). The advantage of the transabdominal approach is that a screening for an adrenal mass is facilitated. Asymptomatic volunteers with a polycystic ovary are a functionally distinct but heterogeneous population, J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009, Section of Adult and Pediatric Endocrinology, The University of Chicago , USA. Gynecologic imaging: comparison of transabdominal and transvaginal sonography, Radiology. 1988, Department of Radiology, West Penn Hospital, Pittsburgh, PA While a polycystic ovary is a criterion for ovarian dysfunction in the setting of hyperandrogenism, in the absence of hyperandrogenism a polycystic ovary is usually a normal variant. Polycystic ovaries are common in the general population,found in about 10 % of regularly menstruating adolescents. Polycystic ovaries in adolescents and the relationship with menstrual cycle patterns, luteinizing hormone, androgens, and insulin, Fertil Steril. 2000, Division of Reproductive Endocrinology and Fertility, Vrije Universiteit Medical Center, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. Once a diagnosis of PCOS has been established, identifying abnormal glucose tolerance or other features of the metabolic syndrome is important because PCOS is a risk factor for the early development of type 2 diabetes mellitus, metabolic syndrome, and their associated risks for sleep-disordered breathing and cardiovascular risk sequelae . Polycystic ovary syndrome is associated with obstructive sleep apnea and daytime sleepiness: role of insulin resistance, J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001, Sleep Research and Treatment Center, Department of Psychiatry, Penn State University College of Medicine, USA. Relationships between sleep disordered breathing and glucose metabolism in polycystic ovary syndrome, J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006, Department of Medicine, University of Chicago, Chicago, USA. About a quarter of adolescents with PCOS meet proposed adolescent criteria for the metabolic syndrome [17,23,24]. screening for abnormal glucose tolerance, performing an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) in adolescents with obesity or other risk factors for diabetes mellitus, even if the fasting blood sugar is normal. This is the recommendations made by the Rotterdam workshop ,the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, and the Androgen Excess and PCOS Society in adult women with PCOS. The prevalence of diabetes was reported to be 2 % based on the fasting blood sugar in one series, and 8 % when based on OGTT criteria in another series of adolescents. In both series, almost all of the adolescents had no symptoms of diabetes. Relationship of adolescent polycystic ovary syndrome to parental metabolic syndrome, J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006, University of Chicago Comer Children's Hospital, Section of Pediatric Endocrinology, USA. Adolescent girls with polycystic ovary syndrome have an increased risk of the metabolic syndrome associated with increasing androgen levels independent of obesity and insulin resistance, J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006, Division of Endocrinology, Metabolism, and Molecular Medicine, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, USA In patients with PCOS: Glucose tolerance should be monitored regularly because a substantial number will experience deterioration in glucose tolerance. As an example, among 25 adolescent and young women followed for a mean of 34 months, the two hour blood glucose deteriorated at an average of 9 mg/dL (0.5 mmol/L) per year . Among the 14 women with PCOS and normal glucose tolerance at baseline, 55 percent experienced deterioration of glucose tolerance when they were retested with an OGTT. Among the 14 women with PCOS and impaired glucose tolerance at baseline, 29 percent progressed to diabetes. Prevalence of impaired glucose tolerance and diabetes in women with polycystic ovary syndrome, Diabetes Care. 1999, Department of Medicine, University of Chicago, Illinois, USA. PCOS is a risk factor for endometrial carcinoma. The basis of the risk is multifactorial: arise from the combined effects of unopposed estrogens on the endometrium, caused by chronic oligo-anovulation and progesterone resistance, obesity, hyperinsulinemia, and hyperandrogenism. Polycystic ovary syndrome and endometrial cancer, Semin Reprod Med. 2008, University Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Royal Free and University College Medical School, University College London, London, United Kingdom. Polycystic ovary syndrome increases the risk of endometrial cancer in women aged less than 50 years: an Australian case-control study, Cancer Causes Control. 2010, School of Population Health, The University of Queensland, Herston Road, Herston, QLD 4006, Australia. Progesterone Resistance in PCOS Endometrium: A Microarray Analysis in Clomiphene Citrate-Treated and Artificial Menstrual Cycles, J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Greenville Hospital System, Greenville, South Carolina . There is a high frequency of PCOS and metabolic syndrome among immediate relatives of individuals with PCOS. According to one study, approximately one-half of sisters of PCOS have an elevated serum testosterone level, and half of these in turn have menstrual irregularity and thus meet NIH criteria for PCOS . Evidence for a genetic basis for hyperandrogenemia in polycystic ovary syndrome, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998 Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Pennsylvania State University College of Medicine, Hershey, PA 17033, USA. In another study, ¼ of sisters met Rotterdam criteria for PCOS, having hyperandrogenism and a polycystic ovary, although menses were ovulatory . Ovarian morphology is a marker of heritable biochemical traits in sisters with polycystic ovaries, J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008, Institute of Reproductive and Developmental Biology, Imperial College London,UK. Treatment for PCOS in adolescents is directed at the following clinical manifestations: Menstrual irregularity Cutaneous hyperandrogenism, primarily hirsutism and acne . Obesity and insulin resistance. Menstrual irregularity should be treated in adolescents with PCOS: chronic anovulation increases the risk of developing endometrial hyperplasia, which is associated with endometrial carcinoma. Anemia can result from dysfunctional uterine bleeding or menorrhagia. the first-line treatment. OCPs induce regular menstrual periods with a higher degree of reliability than other forms of treatment. Progestin • Inhibits endometrial hyperplasia. proliferation , preventing Estrogen • inhibits the activity of the hypothalamic-pituitarygonadal axis, • reducing ovarian androgen production as well as increasing (SHBG) levels. • decreased concentrations of unbound testosterone. • OCP will normalize androgen levels within 18 - 21 days Norgestimate: a potent progestin with low androgenic effect and is combined with ethinyl estradiol: 35 mcg (in Ortho-TriCyclen®). It is especially useful for patients with associated acne vulgaris, for which it has received (FDA) approval. There is variable absorption of this medication, and adjustment of dose may be necessary. • Ethynodiol diacetate: a progestin of low androgenic potential, is combined with ethinyl estradiol: 35 or 50 mcg (in Zovia® 1/35-28 or 1/50-28, respectively). The 1/50 preparation is useful for patients who require a large dose of estrogen, such as those with obesity or dysfunctional uterine bleeding. After three months, the efficacy of treatment is assessed by evaluating clinical symptoms and androgen levels. If the treatment is effective, as a general rule, OCPs should be continued until the patient is gynecologically mature (five years postmenarcheal) or has lost a substantial amount of excess weight. At that point, withholding treatment for a few months to allow recovery of suppression of pituitary-gonadal function and to ascertain whether the menstrual abnormality is persistent is advisable. In doing so, however, one must keep in mind that the anovulatory cycles of PCOS lead to relative infertility, not absolute infertility. If treatment is not successful in reducing androgen levels, the patient either has an unusually prominent component of functional adrenal hyperandrogenism to the PCOS, OR the diagnosis of PCOS should be questioned. Limitations : The role of OCPs in the management of PCOS in adolescents may be limited for several reasons: may make weight loss more difficult to attain because it promotes salt and water retention. OCPs do not permit conception if and when it is desired. In perimenarcheal girls with short stature who have open epiphyses, OCPs are contraindicated because OCPs contain growth-inhibitory amounts of estrogen. Concerns have been raised that the incompletely mature adolescent neuroendocrine system may have heightened risk for post-pill amenorrhea and infertility [6]. However, this hypothetical concern is based on observations in other patient groups undergoing treatment with high-dose estrogens during adolescence, and its relevance to girls with PCOS is unclear. Oestrogen treatment to reduce the adult height of tall girls: long-term effects on fertility, Lancet. 2004, Menzies Research Institute, University of Tasmania, Private Bag 23, Hobart 7001, Australia Other risks of OCPs are similar in adolescents with PCOS to those without PCOS. There is a risk of venous thromboembolism with use of OCPs that is primarily related to the dose and duration of estrogen use, although third generation progestins such as drospirenone confer about a twofold independent risk for first-time users . Risk of non-fatal venous thromboembolism in women using oral contraceptives containing drospirenone compared with women using oral contraceptives containing levonorgestrel: case-control study using United States claims data, BMJ. 2011, Boston Collaborative Drug Surveillance Program, Boston University , USA. Hormonal contraception and risk of venous thromboembolism: national follow-up study, BMJ. 2009, Gynaecological Clinic, Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen University, Denmark. Menstrual irregularities in sexually mature adolescents often can be controlled with cyclic progestin alone. Transient reduction in androgen levels is variably achieved during cyclic therapy, but this is insufficient to expect improvement in hirsutism or hirsutism equivalents . Effect of oral micronized progesterone on androgen levels in women with polycystic ovary syndrome, Fertil Steril. 2002, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology The University of Alabama at Birmingham, USA. Micronized progesterone (Prometrium®, 100 to 200 mg given orally at bedtime) or medroxyprogesterone acetate (Provera®, 10 mg given orally at bedtime) can be used for 7 to 10 days out of each month or cycle. There is considerable controversy about the efficacy and safety of glucocorticoid therapy for PCOS . Glucocorticoid therapy does not result in consistent ovulation in patients with PCOS, even in those with a prominent component of functional adrenal hyperandrogenism . Ovulation after glucocorticoid suppression of adrenal androgens in the polycystic ovary syndrome is not predicted by the basal dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate level, J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999, Department of Obstetrics/Gynecology, The University of Alabama at Birmingham, USA used rarely in lieu of OCPs to regulate menstrual cyclicity or suppress ovarian function in the unusual patient who cannot tolerate OCPs and for whom progestins do not suffice. GnRH therapy is generally not recommended in adolescents younger than 16 years of age because of concerns regarding bone mineral accrual. Patients who receive GnRH agonist therapy also should be treated with low-dose physiologic estradiol and cyclic progestin add-back therapy (eg, 100 mcg estradiol transdermal patch) to maintain vaginal lubrication and to ensure bone mineral accrual if used during adolescence. Bone mineral density should be monitored during therapy. Hyperandrogenism is clinically manifested in 2/3 of cases by hirsutism or equivalent cutaneous findings including acne vulgaris, pattern alopecia, seborrhea, hyperhidrosis, and hidradenitis suppurativa. Hirsutism can be treated by cosmetic and dermatologic measures, and/or by medical endocrinologic therapy. Shaving Eflornithine hydrochloride cream (Vaniqa®) is a topical agent that is FDA approved for the removal of unwanted facial hair in women. Laser therapy removes hair permanently by thermal destruction of the dermal papilla. FDA-approved devices will permanently reduce hair density by 30 % or more with three to four treatments of a site. The goal of endocrinologic therapy is to decrease the effect of excess androgens by: Reducing their production Reducing serum free androgen levels by increasing androgen binding to plasma-binding proteins Blocking androgen action at the level of target organs (eg, hair follicle) effective in typical PCOS patients in whom functional ovarian hyperandrogenism is the predominant source of androgen excess. The 2008 Endocrine Society Guidelines suggest oral contraceptives (OCP) as the first-line drug for pharmacologic therapy. OCPs lower serum free testosterone levels mainly by decreasing ovarian production via suppression of serum gonadotropin levels and increasing sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG) levels. They also modestly lower dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) sulfate levels. The use of OCPs prevents further transformation of vellus to terminal hairs that occurs with androgen exposure. In most patients with PCOS, treatment with OCPs can be expected to arrest progression of hirsutism, reduce the need for shaving by about half, and improve acne within 3 M. It is reasonable to check androgen levels after three months of therapy to determine that androgen levels are lowered, as expected in typical PCOS. The OCP preparation selected should have minimal androgenic activity. the combination of norgestimate/ethinyl estradiol has FDA approval for the treatment of acne vulgaris. A comparison of controlled trials for the treatment of acne suggested drospirenone and norgestimate (ethynodiol diacetate was not included) were beneficial in the treatment of severe facial acne. Selecting an oral contraceptive agent for the treatment of acne in women, Am J Clin Dermatol. 2004, Department of Dermatology, University Medical Center , The Netherlands. Antiandrogenic therapy, inhibits binding of androgen to its receptor, required if there is to be substantial improvement of hirsutism. The 2008 Endocrine Society Clinical Guidelines on hirsutism suggest adding an antiandrogen in patients taking OCPs who feel that their cosmetic response is suboptimal after six months. Although there is considerable individual variation, antiandrogenic therapy reduces hirsutism by onethird, on average. Antiandrogens act by inhibiting the androgeninduced transformation of vellus to terminal hairs Antiandrogens should be prescribed with an OCP because they may cause menstrual disturbance and their potential teratogenic feminization of the male fetus. Antiandrogens have only a modest effect on the metabolic abnormalities associated with PCOS. Treatment of hirsutism, hyperandrogenism, oligomenorrhea, dyslipidemia, and hyperinsulinism in nonobese, adolescent girls, J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000, Endocrinology Unit, Hospital Sant Joan de Déu, University of Barcelona, Spain The antiandrogens include the following: Spironolactone : probably is the safest and most potent antiandrogen available in the United States . the recommended choice for antiandrogen therapy. It lowers hirsutism by approximately 1/3, which is demonstrated by a decrease in the hirsutism score using the Ferriman-Gallwey system . starting with 100 mg twice a day until maximal effect has been achieved and then reducing the dose to 50 mg twice a day for maintenance therapy as tolerated. Administered in these doses, spironolactone usually is well tolerated, but fatigue and hyperkalemia may limit its usefulness. Laboratory testing of electrolytes and liver function tests should be performed one to two weeks after initiation of spironolactone therapy. A prospective randomized trial comparing finasteride to spironolactone in the treatment of hirsute women., J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1995, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Southern California , USA. Cyproterone acetate: is a progestin with antiandrogenic activity that is effective for the treatment of hirsutism. Iavailable as a combination OCP containing ethinyl estradiol and low-dose cyproterone acetate (5 mg) (Diane®). Flutamide: is a more specific antiandrogen with efficacy similar to that of cyproterone. Its use has been limited by the risk of fatal hepatocellular toxicity. The 2008 Endocrine Society Guidelines suggest against the routine use of flutamide because of its potential hepatotoxicity, expense, and the availability of other effective antiandrogens. Finasteride: interferes with androgen action by competitively inhibiting 5α-reductase, type 1. It has seemed slightly less effective than spironolactone in some studies on the treatment of women with hirsutism. However, metaanalysis of the limited available data has not shown a significant difference in efficacy between these treatments . Clinical review: Antiandrogens for the treatment of hirsutism: a systematic review and metaanalyses of randomized controlled trials., J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008, Knowledge and Encounter Research Unit, Mayo Clinic College of Medicine, USA The treatment of obesity improves ovulation, acanthosis nigricans, androgen excess, and cardiovascular risk in patients with PCOS. Weight reduction is indicated in obese patients with PCOS as part of a program to reduce cardiovascular risk factors . Diet and exercise are the first-line treatment for obese adolescents with PCOS as for obese individuals without PCOS. Polycystic ovary syndrome in adolescence, Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2005, Department of Pediatrics, The University of Chicago Pritzker School of Medicine, USA Assessment of cardiovascular risk and prevention of cardiovascular disease in women with the polycystic ovary syndrome, J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010, Oklahoma University Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City, USA. Obesity is of major importance in the insulin resistance of PCOS, Insulin-resistant hyperinsulinism is an important extrinsic factor in the pathogenesis of PCOS and its complications. As a result, lowering the insulin levels in adolescents with PCOS may be beneficial. The main known biochemical action of metformin is to reduce insulin levels primarily by directly inhibiting hepatic glucose output. It tends to suppress appetite and enhance weight loss. In adolescents with PCOS, metformin is used as an adjunct to management of obesity and the related insulin-resistant metabolic abnormalities. Its effectiveness is minimized in the absence of weight control , which may be why insulin levels are inconsistently lowered in treated patients . Effects of metformin on insulin secretion, insulin action, and ovarian steroidogenesis in women with polycystic ovary syndrome, J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997, Department of Medicine, University of Chicago,USA. Thiazolidinediones increase insulin sensitivity primarily by promoting lipid mobilization from the bloodstream via activation of peroxisome-proliferator-related receptors . Thiazolidinediones, N Engl J Med. 2004, Division of Diabetes, Department of Medicine, University of Helsinki, Finland Troglitazone,: the initial thiazolidinedione, decreased androgen levels in women with PCOS but has been withdrawn from the market in the United States and the United Kingdom because of the risk of hepatotoxicity. Pioglitazone: is the safest of the newest generation of thiazolidinediones that are FDA approved for treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. In small, randomized trials, this class of drugs appears to increase ovulation and decrease androgen levels. Unfortunately, these drugs also increase weight gain. Although pioglitazone is less toxic than troglitazone, a few cases have been reported of pioglitazone-induced reversible hepatic toxicity. Pioglitazone has been withdrawn from the market in France and Germany because of an association with bladder cancer. Polycystic ovary syndrome is the most common cause of anovulatory symptoms and hyperandrogenism in women and can present during adolescence. Recognizing and treating PCOS in adolescents is important beyond management of the presenting symptoms because PCOS increases the risk of developing infertility, endometrial hyperplasia and carcinoma, type 2 diabetes mellitus, metabolic syndrome, and possibly cardiovascular disease. PCOS is currently defined as otherwise unexplained hyperandrogenism (eg, hirsutism, persistent acne, pattern alopecia), and ovarian dysfunction manifest as either menstrual irregularity (eg, oligo- or amenorrhea, irregular bleeding) or polycystic ovaries. In adolescents, we suggest using the NIH diagnostic criteria: otherwise unexplained hyperandrogenism (eg, hirsutism, persistent acne, pattern alopecia) and menstrual irregularity (eg, oligo- or amenorrhea, irregular bleeding). Once a diagnosis of PCOS has been established, it is important to identify and monitor for abnormal glucose tolerance and other features of the metabolic syndrome because PCOS is a risk factor for the early development of type 2 diabetes mellitus and metabolic syndrome, and their associated morbidity. Immediate family members are also at risk for these metabolic dysfunctions. Several treatment options are available for adolescents with PCOS . The choice of therapy depends on the individual adolescent's symptoms, her goal for treatment, and preferences . We suggest the use of combination oral contraceptives as first-line treatment for adolescents who suffer the menstrual and cutaneous symptoms of PCOS (Grade 2B). If the adolescent patient is unable or unwilling to take combination OCP, other therapeutic options for menstrual irregularities include progestin alone, lowdose glucocorticoid therapy, and gonadotropin releasing (GnRH) agonist therapy with add-back estrogen. We suggest that hirsutism initially be treated by cosmetic and physical measures (Grade 2B). We suggest that OCPs be the initial pharmacologic agents used in treating patients with hirsutism who fail to respond adequately to cosmetic and dermatologic measures (Grade 2C). For substantial improvement, we suggest adding spironolactone, which should only be used in combination with OCPs (Grade 2B). Weight loss in obese adolescents with PCOS improves ovulation, acanthosis nigricans, and hyperandrogenemia. Insulin-lowering agents improve ovulation in about half of cases, and modestly reduce androgen levels . They are not as effective as OCPs in controlling menstrual cyclicity or hirsutism. Metformin is the only one of these agents that we use in adolescents with PCOS, and is used as an adjunct to weight-control measures and to treat co-existent insulinresistant metabolic abnormalities.