Compiled Masters Thesis January 20 - MacSphere

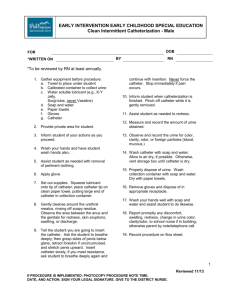

advertisement