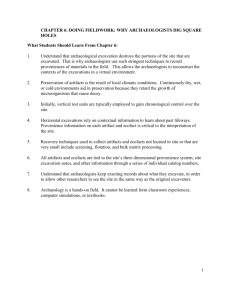

Analyzing the Evidence

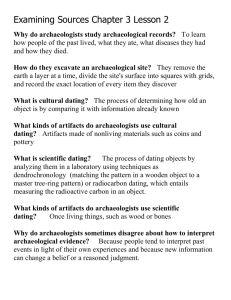

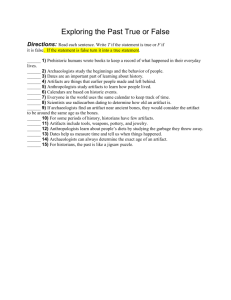

advertisement

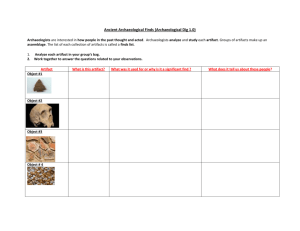

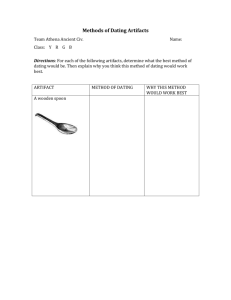

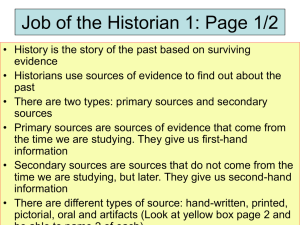

• Once archaeologists have found a site and recovered artifacts and other materials from it, they are ready to begin “reading” what they have found to learn the story of the past. • The reading of the archaeologists is called analysis. • Much of what is lost and discarded by humans never survive. Much of what does survive comes to us in fragments and in a fragile, deteriorated state. • Before doing analysis, then, archaeologists and paleoanthropologists must first conserve and reconstruct the materials they have found. • Conservation is the process of treating artifacts to stop decay and if possible, reverse the deterioration process. • Some conservation is very simple, involving only cleaning and drying the item. • Some conservation is highly complex, involving longterm chemical treatment and long-term storage under controlled conditions. • The 5,000 year-old “Ice Man” found in 1993 has to be kept permanently in glacial-like conditions. • Reconstruction is like building a three-dimensional puzzle where you’re not sure which pieces belong and you know not all of the pieces are there. • First, archaeologists typically examine the form or shape of an artifact. • For most common artifacts, such as ceramics, forms are known well enough to be grouped into a typology or set of types, which is the primary purpose of formal analysis. • Typology provide a lot of information about the artifact, including: • Its age • Species and culture where it comes from. • Sometimes, how it was made, used, or exchanges. • Reconstruction is like building a three-dimensional puzzle where you’re not sure which pieces belong and you know not all of the pieces are there. • Second, archaeologists often measure artifacts, recording their size in various, often strictly defined, dimensions. This is called metric analysis. • Third, archaeologists, often attempt to understand how an artifact was made. • By examining the materials the artifact is made from and how that material was manipulated, archaeologists can learn about the technology, economy, and exchange system of the people who made the artifact. • Reconstruction is like building a three-dimensional puzzle where you’re not sure which pieces belong and you know not all of the pieces are there. • Finally, archaeologists attempt to understand how an artifact was used. • Knowing how an artifact was used gives the archaeologist a direct window onto ancient life. • For stone, bone and wood tools, there is a technique called usewear analysis which can determine how a tool was used through the careful examination of the kind of wear on its edges. • Knowing how an artifact was made allows the archaeologists to understand the technology and technical abilities of people in the past. For example: Thomas Wynn analyzed both the final forms and the methods used by early humans – Homo erectus – to make stone tools roughly 300,000 years ago. He found that manufacturing these tools was a multistage process, involving several distinct steps and several distinct stoneworking techniques to arrive at the finished product. He then took his information and evaluated it in term of measure of human cognitive ability developed by Jean Piaget, and concluded that the people who made these tools probably had organizational abilities similar to those of modern humans. • Knowing how an artifact was used allows the archaeologists to know something of people’s behavior and activities. Lawrence Keeley conducted detailed usewear analyses on Acheulian hand axes made by Homo erectus peoples and found that they had a variety of uses. • • • • Some cut meat. Others for wood To dig in the group (probably for edible roots). Therefore hand axes appear to have been multipurpose tools for our Homo erectus ancestors – something like a Swiss Army knife. • Ecofacts are diverse, and what archaeologists and paleoanthropologists can learn from them is highly diverse as well. • Paleontologists (studying humans or other species) can tell a great deal about an extinct animal from its fossilized bones or teeth, but that knowledge is based on much more than just the fossil record itself. • Paleontologists rely on comparative anatomy to help reconstruct missing skeletal pieces • New techniques, such as electron microscopy, CAT scans and computer provide much information about how the organism may have moved about. • Chemical analysis of fossilized can suggest what the animal typically ate. • Paleontologists are also interested in the surroundings of the fossil finds • Much of the evidence for primate evolution comes from teeth, which are the most common animal parts (along with jaws) to be preserved as fossils. • Animals vary in dentition – the number and kinds of teeth they have, their size, and their arrangement in the mouth. • Dentition provides clues to evolutionary relationships because animals with similar evolutionary histories often have similar teeth. • For example, no primates, living or extinct, has more than two incisors in each quarter of the jaw. That feature, along with others, distinguishes the primates from earlier mammals, which had three incisors in each quarter. • Dentition also suggests the relative size of an animal and often offer clues about its diet. • For example, comparison of living primates suggested that fruit eaters have flattened, rounded tooth cusps, unlike leaf- and insect- eaters, which have more pointed cusps. • Paleontologists can tell much about an animal’s posture and locomotion from fragments of its skeleton. • Arboreal quadrupeds have front and back limbs of about the same length; because their limbs tend to be short, their center of gravity is close to the branches on which they move. They also tend to have long grasping fingers and toes. • Paleontologists can tell much about an animal’s posture and locomotion from fragments of its skeleton. • Terrestrial quadrupeds are more adapted for speed so they have longer limbs and shorter fingers and toes. Disproportionate limbs are more characteristics of vertical clingers and leapers and brachiators (species that swing through the branches). • Vertical clingers and leapers have longer, more powerful hind limbs, branchiators have longer forelimbs. • Because we cannot remove features to the lab, we cannot subject them to the same range of analyses as artifacts, ecofacts, and fossils. • Archaeologists developed a number of powerful tools to analyze features in the field. • The primary one is detailed mapping, usually using a surveyor’s transit. • Geographic information system (GIS) allow the archaeologist to produce a map of the features on a site and combine that map with information about other archaeological materials found there. • Archaeologists do not study fossils and artifacts as individual objects. • They put all the materials discovered in one site in context. This means how and why are the artifacts and other materials are related – This is what archaeology is all about. • Fossils and artifacts maybe beautiful or interesting by themselves, but it is only when they are placed in context with the other materials found on a site that we are able to “read” and tell the story of the past. • An important part of putting artifacts and other materials into context is putting them in chronological order • Dating methods include: • Relative dating is used to determine the age of a specimen. • Absolute dating or chronometric dating is used to measure how old a specimen or deposit is in years. • Stratigraphy • The study of how different rock and solid formations are laid down in successive layers or strata. • Oldest layers are generally deeper or lower than more recent layers. • The earliest, and still the most common used. • Indicator artifacts or ecofacts are used to establish a Stratigraphy sequence. • If a site has been disturbed, Stratigraphy will not be a satisfactory way to determine relative age. • Many of the absolute dating methods are based on the decay of a radioactive isotope. Because the rate of decay is known, the age of the specimen can be estimated, within a range of possible error. • Radiocarbon Dating or Carbon 14 dating • The most popular known methods of determining the absolute age of a specimen. • All living matter possesses a certain amount of radioactive form of carbon (Carbon 14). After an organism dies, it no longer takes in any of the radioactive carbon. Carbon-14 decays at a slow but steady pace and reverts to nitrogen-14. The rate at which carbon decays –its half life – is known: C-14 has a half life of 5,730 years • Thermoluminescence Dating • Many minerals emit light when they are heated. • This cold light comes from the release, under heat, of “outside” electrons trapped in the crystal structure. • Thermoluminescence dating makes use of the principle that if an object is heated at some point to a high temperature it will release all the trapped electrons it held previously. The amount of Thermoluminescence emitted when the object is tested during testing allows researchers to calculate the age of the object. • Thermoluminescence dating is well suited to sample of ancient pottery, brick, tile, and other objects that are made at high temperatures. • Electron Spin Resonance Dating • Measures trapped electrons then expose them to magnetic fields. • Paleomagnetic Dating • When rock of any kind form, it records the ancient magnetic field of the earth. Since the earth’s magnetic field has reversed itself many times, the geomagnetic patterns in rocks can be used to date the fossils within the rocks. • Potassium-Argon Dating • Potassium-40 decays at an established rate and forms argon40. The half-life of K-40 is a known quantity, so the age of a material containing potassium can be measured by the amount of K-40 c0mpared with the amount of Ar-40. Potassium-Argon Dating us used to date samples from 5,000 years up t0 3 billion years old • Uranium-Series Dating • The decay of two kinds of uranium U-235 and U-238 into other isotopes. • Used especially in caves where stalagmites and other calcite formations form, because water usually contains uranium but not thorium. • Fission-Track Dating • It entails counting the number of paths or tracks etched in the sample by the fission-explosive division- of uranium atoms as they disintegrate. • One goal is the description or reconstruction of what happened in the past. • Archaeologists attempt to determine how people lived in a particular place at a particular time, and when and how their lifestyle changed • Another goal is testing specific explanations about human evolution and behavior. • Understand general trends and patterns in human biological and cultural evolution. • Archaeology does not simply describe past cultures. It can also have a profound effect on living people. • For example, many people find the idea of archaeologists excavating, cleaning, and preserving the remains of ancestors to be offensive. Therefore, archaeologists must be sensitive to the desires and beliefs of the populations that descend from the ones they are researching. • Artifacts from some ancient cultures are in great demand by art and antiquities collectors, and archaeological digs can lead to uncontrolled looting if archaeologists are not careful about how and to whom they report their discoveries. • Archeologists must report all their findings to the public. Since by excavating a site, they damage it, they must document everything for future archaeologists who are excavating the same site.