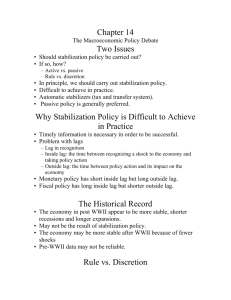

automatic stabilizers

advertisement

® CHAPTER 15 Stabilization Policy A PowerPointTutorial To Accompany MACROECONOMICS, 7th. Edition N. Gregory Mankiw Tutorial written by: Mannig J. Simidian B.A. in Economics with Distinction, Duke University 1 M.P.A., Harvard University Kennedy School of Government M.B.A., Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) Sloan School of Management Chapter Fifteen To many economists, the case for active government policy is clear and simple. Recessions are periods of high unemployment, low incomes, and increased economic hardship. The model of aggregate demand and aggregate supply shows how shocks to the economy can cause recessions. It also shows how monetary and fiscal policy can prevent recessions by responding to these shocks. These economists consider it wasteful not to use these policy instruments to stabilize the economy. Other economists are critical of the government’s attempts to stabilize the economy. These critics argue that the government should take a hands-off approach to macroeconomic policy. At first, this view might seem surprising. If our model shows how to prevent or reduce the severity of recessions, why do these critics want the government to refrain 2 Chapterfrom Fifteen using monetary and fiscal policy for economic stabilization? Economists distinguish between two types of lags that are relevant for the conduct of stabilization policy: the inside lag and the outside lag. The inside lag is the time between a shock to the economy and the policy action responding to that shock. This lag arises because it takes time for policymakers first to recognize that a shock has occurred and then to put appropriate policies into effect to deal with it. The outside lag is the time between a policy action and its influence on the economy. This lag arises because policies do not immediately influence spending, income, and employment. Chapter Fifteen 3 Some policies, called automatic stabilizers, are designed to reduce lags associated with stabilization policy. Automatic stabilizers are policies that stimulate or depress the economy when necessary without any deliberate policy change. For example, the system of income taxes automatically reduces taxes when the economy goes into a recession, without any change in the tax laws, because individuals and corporations pay less tax when their incomes fall. Similarly, the unemployment insurance and welfare systems automatically raise transfer payments when the economy moves into a recession, because more people apply for benefits. One can view these automatic stabilizers as a type of fiscal policy without any inside lag. Chapter Fifteen 4 As we learned, since policy only affects the economy after a long lag, successful stabilization requires the ability to predict future economic conditions. One way forecasters try to look ahead is with leading indicators. A leading indicator is a data series that fluctuates in advance of the economy. A large fall in a leading indicator signals that a recession is more likely to occur in coming months. Another way forecasters look ahead is with macroeconometric models, which have been developed by both government agencies and by private firms. They seek to predict variables such as unemployment and inflation and other endogenous variables. Chapter Fifteen 5 Nobel laureate Robert Lucas emphasized that people form expectations of the future. Expectations play a crucial role because they influence all sorts of economic behavior. Both households and firms decide to consume and invest based on expectations of future earnings. These expectations depend on many things, including the policies of the government. He argues that traditional methods of policy evaluation such as those that rely on standard macroeconometric models—do not adequately take into account this impact of policy on expectations. This criticism of traditional policy evaluation is known as the Lucas Critique. 6 Chapter Fifteen Policy is conducted by rule if policymakers announce in advance how policy will respond to various situations and commit themselves to following through on this announcement. Policy is conducted by discretion if policymakers are free to size up events as they occur and choose whatever policy the policymakers consider appropriate at the time. The debate over rules versus discretion is distinct from the debate over passive versus active policy. Policy can be conducted by rule and yet be either passive or active. An active policy rule might specify: money growth = 3% + (Unemployment Rate – 6%) This rule tries to stabilize the economy by raising money growth when the economy is in a recession. Chapter Fifteen 7 Opportunistic policymakers take advantage of an exploitable Phillip’s curve and face naïve voters who forget the past, are unaware of the policymakers’ incentives, and do not understand how the economy works. In particular, politicians don’t take into account the tradeoff between inflation and unemployment when their political gain is at stake. Chapter Fifteen 8 Policymakers announce in advance the policy they will follow to influence the expectations of private decision-makers. But, later, after the private decision-makers have acted on the basis of their expectations, these policymakers may be tempted to renege on their announcement. Chapter Fifteen 9 1) To encourage investment, the government announces that it will not tax income from capital. But, after factories are built, the government is tempted to raise taxes. 2) To encourage research, the government announces that it will give a temporary monopoly to companies that discover new drugs. But, after the drugs have been discovered, the government is tempted to revoke the patent. 3) To encourage hard work, your professor announces that this course will end with an exam. But, after you studied and learned all the material, the professor is tempted to cancel the exam so that he or she won’t have to grade it. Chapter Fifteen 10 Monetarists are economists who advocate that the Fed keep the money supply growing at a steady rate. Monetarists believe that fluctuations in the money supply are responsible for most large fluctuations in the economy. P LRAS P* AD'' AD' AD Chapter Fifteen Y Y' Y'' Y Here we can see that this economy is growing (LRAS is shifting rightward) so continued increases in the supply of money (via +DAD) don’t necessarily imply increases in inflation. 11 A second policy rule that economists widely advocate is nominal GDP targeting. Under this rule, the Fed announces a planned path for nominal GDP. If nominal GDP rises above the target, the Fed reduces money growth to dampen aggregate demand. If it falls below the target, the Fed raises money growth to stimulate aggregate demand. Because a nominal GDP target allows monetary policy to adjust to changes in the velocity of money, most economists believe it would lead to greater stability in output and prices than a monetarist policy rule. Chapter Fifteen 12 In the late 80s, many of the world’s central banks adopted some form of inflation targeting. Sometimes inflation targeting takes the form of central bank announcing its policy intentions. The Federal Reserve has not adopted an explicit policy of inflation targeting (although some commentators have suggested that it is, implicitly, targeting inflation at about 2 percent). Chapter Fifteen 13 We have looked at whether policy should take an active or passive role in responding to fluctuations in the economy, and whether policy should be conducted by rule or discretion. Although there is persistent debate between both sides, there is one clear conclusion: no simple and compelling case for any particular view of macroeconomic policy has been made. In the end, one must weigh the various political and economic arguments and decide what role the government should play in stabilizing the economy. Chapter Fifteen 14 Inside and Outside lags Automatic Stabilizers Lucas critique Political business cycle Time Consistency Monetarists Inflation Targeting Chapter Fifteen 15