FL 2013

advertisement

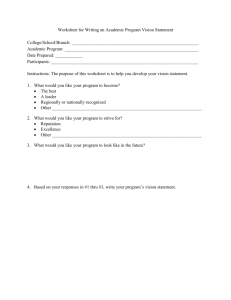

HIS 232.I50: Development of the U.S. from the Civil War ONLINE COURSE SYLLABUS FL 2013 Credit hours: Semester: Section: Location: Instructor: Office: E-mail: Phone: 3 FL 2013 232.I50 Online Larissa Nemoianu JM 145 NemoianLarissaG@jccmi.edu 517-796-8542 Office Hours: Mondays 10:00 1:00 AM PM – – 11:00 3:30 AM PM Tuesdays 12:00 3: 00 PM PM _ _ 1:00 3:30 PM PM Wednesdays 10:00 1:00 AM PM – – 11:00 3:30 AM PM Thursday 12:00 3: 00 PM PM _ _ 1:00 3:30 PM PM Other hours by appointment REQUIRED: America, A narrative History, by George Brown Tindall and David Emory Shi, brief ninth edition, Norton, volume 2 Very helpful: the book web site for assignments, practice tests, sources, etc. http://www.wwnorton.com/college/history/america9/brief/ch/17/studyplan.aspx Very Important: If you want to finish the class earlier you can, I will open the exams early for you, and all you need to do is to give me a call! You can not finish the class later. COURSE DESCRIPTION American History 232 is a one-semester college level course. This class puts into perspective the major economic, political, diplomatic, and social developments impacting the United States from Reconstruction into the third quarter of the twentieth century. INTRODUCTION: History 232 is an introductory level course that provides insight into the growth and development of the United States from the Civil War. The course treats the politics, religion, economics, science and HIS 231, FL2013 1 philosophy through most of the twentieth century. Emphasis is placed on analyzing the historical events of the United States and gaining perspective on their relationship to the present. You will be expected to devote considerable time to the reading and written assignments, observe the time lines incorporated in the syllabus and other course documents, and maintain civility and decorum in all communication with the instructor and students in the class. All work turned in for credit must be your own. The principle course objectives include comprehension of the events of American history through the middle of the twentieth century, the critical and analytical evaluation of those events, and the improvement of writing skills as a tool to express ideas. Your written work must be in your own words. Online classes require discipline and independence. You are responsible for your learning. I am available to assist you and to provide guidance. To succeed you must maintain a schedule and complete assignments on time. As in a traditional classroom, there are penalties for late or incomplete assignments. This course will contribute to the following Associate Degree Outcomes: ADO 5 Understanding human behavior and social systems Students will learn to: * Recognize factors that determine and govern human behavior. Distinguish between individual and external factors. * Understand the methods of analysis and interpretation used by historians to explain events and the role of personality in history * Understand the connection between the economic, social, and political systems in the entire human history (specific in US history) * Understand two social and political systems (British and American) and the limitation of each * Characterize the evolution of the "American character" by analyzing the combination of influences, such as various traditions, environmental conditions, and opportunities. ADO 7: Critical Thinking Students will learn to: * Recognizes need for questions and for questioning. * Distinguishes between fact, opinion and inference in reading primary and secondary sources. * Identifies the nature of bias in both primary and secondary historical sources. * Recognizes how the context of information can be manipulated to impact conclusions. THIS IS NOT A SELF-PACED CLASS HIS 231, FL2013 2 STUDENT REQUIREMENTS: My evaluation of your work will be based on your effort and on your abilities demonstrated throughout the class. The class calendar, my methods of teaching, the evaluation criteria, could change depending on the class effort and direction Each student will spend at least 9 hours per week preparing for class. 1. Read the "Learning Goals" at the beginning of each chapter. (The goals summarize the key points in the course and provide a guide for studying the information for the examination questions.) 2. Read the outlines and power points for each chapter 3. Read the textbook chapter at least twice. The first time scan the chapter topics reading the major points, and then the second time, concentrate on trying to understand the information, which will require asking yourself questions about what you are reading. 4. Paraphrase the definitions for each term and concept. 5. Answer discussion questions 6. Take the examinations. 7. Upload in time the 4 written assignments Learn to become an Active Reader. Don't just read and answer questions. It's important that you take notes while you are reading. If you have a question about something you've read, write it down. Go back through the material and find the answer. You might even have questions about concepts in the chapters that aren't answered to your satisfaction. Post those on the bulletin board to get feedback from the other class members. LEARNING ACTIVITIES: Various learning activities will be used to accomplish the course goals. Text and computer online readings are used to introduce materials, methods, and concepts. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Read the chapters in the textbook. Read the outline on the book web Participate in class discussion. Read the four documents assigned and complete the worksheets. Take examinations. EVALUATION Students can accumulate 500 points: 420 from the exams 40 from the assignments 40 points from class discussions GRADING POLICY: You are responsible to check your grades weekly; if the grades are not posted, or if you see a mistake, call or email me immediately. The grade you earn in the course will be based on the average grade you receive on all graded work. HIS 231, FL2013 3 The grades are not negotiable: each student is responsible for the grades he/she earns and for checking weekly on Jet Net the posted points. If a student finds a mistake, or thinks that he/she did not get credit for a discussion etc, he/she should contact me immediately. GRADING SCALE: The exam with the lowest grade will be dropped 4.0 450 to 500 3.5 425 to 449 3.0 400 to 424 2.5 350 to 399 2.0 300 to 349 1.5 250 to 299 1.0 200 to 249 0.5 150 to 199 0.0 under 150 EXAMINATIONS 8 exams are worth 60 points each. Again: The exam with the lowest grade will be dropped. The exams are made up of multiple-choices questions. The exams are online and are not open book; no books and notes are allowed. They can be taken any day of the week they are scheduled. The last day is t e Sunday, at 11:59 PM, of the scheduled week; if you have a problem with your computer go to one of the computer labs. No make- up exam is allowed. If you miss an exam, for any reason, it will be the one exam I will drop. EXAMS SCHEDULE HIS 231, FL2013 Exam 1 : chapters 17 and 18 09/23 to 09/29 Exam 2: chapters 19 and 20 09/30 to 10/06 Exam 3: chapters 21and 22 10/07 to 10/13 Exam 4: chapters 23 and 24 10/21 to 10/27 Exam 5: chapters 25 and 26 10/28 to 11/03 Exam 6: chapters 27 and 28 11//04 to 11/10 Exam 7: chapters 29, 30 and 31 11/18 to 11/24 Exam 8: chapters 32 and 33 12/02 to 12/08 4 RULES FOR THE CLASS DISCUSSIONS 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. Participate in four online discussions at least three times on each posted topic. Each individual is required to thoughtfully comment (start a new message in the “Discussion” section of Jet Net) on the subject. You must post your statement in the first three days of discussion week (Monday, Tuesday or Wednesday) for 5 points. If you post later your statement will be graded as a reply. React to the opinions of one colleague for 3 points and to the second other student for 2 more points. The replies must be on the discussion subject. Your comments to your colleagues' statements should be more than "I agree", "I disagree"; "Good job!", or something similar. Your statements and your replies are not to be personal opinion. If you start with "I think" I will not read the rest of the posting. You must bring arguments to support your position. It is expected that you will provide answers that are complete and thoughtful. Answers should be based on the readings. You may reference information from outside the readings if you choose, but it must be clearly cited. And, please, use proper English in your responses and not codes and language used in instant messaging! If you post your statement and replies on the same day, you will not get credit for your statement. Discussion posted after the due date are not graded. The topics are in your class schedule and the discussion board will be open at the discussion starting date WRITTEN ASSIGNMENTS: there are four (4) written assignments for this class. Each assignment is worth 10 points. The documents for assignments are listed at the end of syllabus. For each assignment: you will read the document (chosen by me), complete the worksheet for the document, and upload the worksheet in the assignment folder. I posted a worksheet form under the class syllabus. You will have to save this form on your computer, answer the questions, and upload the completed worksheet on your assignment on your class site. I will not grade the assignment if you use a different format from the one I posted. Example: Assignment 1: Step 1: read the document Step 2: read the sample worksheet Step 3: answer the questions Step 4: upload your worksheet under the assignment 1 on your Jet Net class site. For assignment 1 you must upload (as an rtf or word document) under Assignment 1 in week 2. You can upload earlier than the beginning of the week, but not after the due date. Late assignments will be penalized with 2 points deducted for every late day. Academic dishonesty (plagiarism* or cheating) will result in a course grade of 0.0. pla·gia·rize: transitive senses: to steal and pass off (the ideas or words of another) as one's own: use (another's production) without crediting the source intransitive senses: to commit literary theft: present as new and original an idea or product derived from an existing source HIS 231, FL2013 5 If you use information from outside sources (and you will have to do it) you must tell what sources you used, even if you used your own words!!! GRADING THE ASSIGNMENTS Again: I will not grade the assignment if you use a different format from the one I posted. Worksheet for: (the title of the document) 1. Who wrote (something about the author, not only his name) and what type of document is this? (Ex. Newspaper, telegram, map, letter, memorandum, etc.) 3 points 2. For what audience was the document written? 1 point 3. Expression. 2 points What do you find interesting or important about this document? Is there a particular phrase or section that you find particularly meaningful or surprising? 4. Connection. 4 points This is the most important part of your assignment. The answer to this question is proving your understanding of history and the relations between different aspect of a civilization, as well as the connections between civilizations. Your answer should reflect the way you connect the document with the material you study. The evaluation of your assignments and your contributions to the class discussions of the material is a discretionary matter. It is my judgment call whether or not your assignment responses and comments on the material reflect sufficient effort and insight. I will check my e-mail every day, including the weekend, so please e-mail me with any questions or concerns. If you do not get an answer from me in 24 hours it will be because I am sick or I have problems with my computer. ASSIGNMENTS: Assignment 1: read and complete the worksheet for "Life on Prairie Farms (1893)" Do not e-mail your worksheet to the publisher; your assignment sheet (the one I posted on your class site) should be uploaded on the Jet Net class site. Due: October 6, at 11: 55 PM Assignment 2: read and complete the worksheet for "The Treason of the Senate" (1906), David Graham Phillips Do not e-mail your worksheet to the publisher; your assignment sheet (the one I posted on your class site) should be uploaded on the Jet Net class site. Due: October 20, 2012, at 11:55 PM Assignment 3: read and complete the worksheet for " Keep the Consumer Dissatisfied, Charles F. Kettering (1929) Do not e-mail your worksheet to the publisher; your assignment sheet (the one I posted on your class site) should be uploaded on the Jet Net class site. Due: November 3, at 11:55 PM Assignment 4: read and complete the worksheet for " Women in War Industries” HIS 231, FL2013 6 Do not e-mail your worksheet to the publisher; your assignment sheet (the one I posted on your class site) should be uploaded on the Jet Net class site. Due: November 10, at 11:55 PM "I" (INCOMPLETE) GRADE POLICY: Policy Summary: This policy defines and establishes the use of an Incomplete Grade “I” course designation in specific instances. A form is attached that must be used when implementing an “I” designation. Policy Statement: Extenuating circumstances sometimes prevent otherwise successful students from completing a course by the end of a semester. Use of the Incomplete Grade designation allows students extra time to finish a course. The instructor and student should work together to determine when the work is to be completed. All work is to be completed no later than the end of the next full-length semester. The instructor will designate the grade earned if the student fails to complete the course objectives within the designated time period. I – Incomplete: The incomplete grade is designed for students with extenuating circumstances to allow them to complete the course requirements after the semester or session has ended. Students may receive an “I” if, in the opinion of the instructor, their work is sufficient in quality, but is lacking in quantity to meet the objectives specified in the course syllabus. The course objectives are to be satisfactorily completed during the next full-length semester or within a shorter period of time as determined by the instructor. If the student does not complete the course within the designated time period, the Registrar will replace the “I” grade with the earned grade as assigned by the instructor. The grade of “I” is not awarded to students who did not attend, or seldom attended, or to those who simply are not pleased with their final grades. Students receiving an “I” submit only the remaining work that had not been completed at the end of the semester. Students do not redo work that had already been graded. WITHDRAWAL/DROP POLICY: It is important to note that if you decide for whatever reason, that you do not want to complete this course, you must officially withdraw by completing a withdrawal form (which can be obtained in the Student Center) on or before the official withdrawal deadline. After that date, your grade will be determined by the grades you've earned. In some cases, this could mean a 0.0 final grade. VERRY IMPORTANT DATE Refund/Drop Date with no W: Drop with a W: Last day to Withdraw: 09/23/2013 09/24/2013 12/052013 GRADES All faculties are required to report each student’s progress through the HQV grade process: H indicates the student is not doing acceptable work and needs Help to be successful. Q indicates the student has not attended and the instructor believes they have unofficially withdrawn (Quit). As a result of a “Q” grade, the student will be dropped from the class. V indicates the instructor Verifies that the student is attending. GRD1 is due: 09/21/2013 GRD2 is due: 10/07/2013 GRD3 is due: 11/02/2013 HIS 231, FL2013 7 Tentative class schedule The instructor can change the schedule, format of the class discussion and/or format of the exams at any time during the semester in order to accommodate the class needs. Week nr. 1 2 Dates Studying Exams, Assignment and Discussions. 09/16 To 09/22 09/23 To 09/29 Ch.17. Reconstruction: North and South Your questions related to class assignments and exams Ch. 18 Big Business and Organized Labor Discussion 1: What factors shaped the growth of labor unions during this period? Explain Discussion is open on September 23 to September 29 Exam 1: chapters 17 and 18 3 4 09/30 To 10/06 10/07 To 10/13 Ch. 19. The South and the West Transformed Ch. 20. The Emergence of Urban America Assignment 1: read and complete the worksheet for "Life on Prairie Farms (1893)" Due date: 10/06, at 11:55 PM Ch. 21. Gilded Age Politics and Agrarian Revolt Discussion 2 In your view what were the reasons for American expansionism at the turn of the twentieth century? What justifications did Americans offer for expansionism? Explain Ch. 22. Seizing. an American Empire Exam 2: chapters 19 and 20 Discussion is open on October 7 to October 13 Exam 3: chapters 21 and 22 5 10/14 To 10/20 Ch. 23. “Making the World Over”: The Progressive Era Assignment 2: nread and complete the worksheet for "The Treason of the Senate" (1906), David Graham Phillips Due date: 10/20, at 11:55 PM 6 10/21 To 10/27 Ch. 24. America and the Great War Discussion 3: Discuss the various causes of the stock market crash, paying particular attention to government policies that helped bring on the crash. Discussion is open on October 21 to October 27 Exam 4: chapters 23 and 24 7 10/28 To 11/03 Ch. 25. The Modern Temper Ch. 26. Republican Resurgence and Decline Assignment 3: read and complete the worksheet for " Keep the Consumer Dissatisfied, Charles F. Kettering (1929) Due date: 11/03, at 11:55 PM Exam 5: chapters 25 and 26 HIS 231, FL2013 8 8 11/04 To 11/10 Ch. 27. New Deal America Ch. 28. The Second World War Assignment 4: read and complete the worksheet for " Women in War Industries” Due date: 11/10 at 11:55 PM Exam 6: chapters 27 and 28 9 11/11 To 11/17 Ch. 29. The Fair Deal and Containment Chapter 30 The 1950s: Affluence and Anxiety in an Atomic Age 10 11/18 To 11/24 Ch. 31. New Frontiers: Politics and social change in the 1960s Discussion 4 What were, in your view, the main domestic achievements of the New Frontier and the Great Society? Which accomplished more? Why? Discussion is open on November 18 to November 24 Exam 7: chapters 29, 30 and 31 11 12 11/25 To 12/01 12/02 To 12/08 Ch. 32: Rebellion And Reaction In The 1960s And 1970s Chapter 33 A Conservative Realignment: 1977–1990 Exam 8: chapters 32 and 33 DOCUMENT FOR ASSIGNMENT 1 Life on Prairie Farms (1893), by E. V. Smalley Please read this document and answer the questions on the worksheet. . . . the life of a poor settler on a homestead claim in one of the Dakotas or Nebraska. Every homesteader must live upon his claim for five years to perfect his title and to get his patent; so that if there were not the universal American custom of isolated farm life to stand in the way, no farm villages would be possible in the first occupancy of a new region in the West without a change in our land laws. If the country were so thickly settled that every quarter-section of land (160 acres) had a family upon it, each family would be half a mile from any neighbor, supposing the houses to stand in the center of the farms, and in any case the average distance between them could not be less. But many settlers own 320 acres, and a few have a square mile of land, 640 acres. Then there are school sections, belonging to the State, and not occupied at all, and everywhere you find vacant tracts owned by Eastern speculators or by mortgage companies, to which former settlers have abandoned their claims, going to newer regions and leaving their debts and their land behind. Thus the average space separating the farmsteads is, in fact, always more than half a mile, and many settlers must go a mile or two to reach a neighbor's house. This condition obtains not on the frontiers alone, but in fairly well peopled agricultural districts. HIS 231, FL2013 9 If there by any region in the world where the natural gregarious instincts of mankind should assert itself, that region is our Northwestern prairies, where a short hot summer is followed by a long cold winter, and where there is little in the aspect of nature to furnish food for thought. On every hand the treeless plain stretches away to the horizon line. In summer, it is checkered with grain fields or carpeted with grass and flowers, and it is inspiring in its color and vastness; but one mile of it is almost exactly like another, save where some watercourse nurtures a fringe of willows and cottonwoods. When the snow covers the ground the prospect is bleak and dispiriting. No brooks babble under icy armor. There is not bird life after the wild geese and ducks have passed on their way south. The silence of death rests on the vast landscape, save when it is swept by cruel winds that search out every chink and cranny of the buildings, and drive through each unguarded aperture the dry, powdery snow. In such a region, you would expect the dwellings to be of substantial construction, but they are not. The new settler is too poor to build of brick or stone. He hauls a few loads of lumber from the nearest railway station, and puts up a frail little house of two, three or four rooms that look as though the prairie winds would blow it down. Were it not for the invention of tarred building-paper, the flimsy walls would not keep out the wind and snow. With this paper, the walls are sheathed under the weatherboards. The barn is often a nondescript affair of sod walls and straw roof. Lumber is much too dear to be sued for dooryard fences, and there is no inclosure about the house. A barbed-wire fence surrounds the barnyard. Rarely are there any tress, for on the prairies trees grow very slowly and must be nursed with care to get a start. There is a saying that you must first get the Indian out of the soil before a tree will grow at all; which means that some savage quality must be taken from the ground by cultivation. In this cramped abode, from the windows of which there is nothing more cheerful in sight than the distant houses of other settlers, just as ugly and lonely, and stacks of straw and unthreshed grain, the farmer's family must live. In the summer there is a school for the children, one, two, or three miles away; but in the winter the distances across the snow-covered plains are too great for them to travel in severe weather; the schoolhouse is closed, and there is nothing for them to do but to house themselves and long for spring. Each family must live mainly to itself, and life, shut up in the little wooden farmhouses, cannot well be very cheerful. A drive to the nearest town is almost the only diversion. There the farmers and their wives gather in the stores and manage to enjoy a little sociability. The big coal stove gives out a grateful warmth, and there is a pleasant odor of dried codfish, groceries, and ready-made clothing. The women look the display of thick cloths and garments, and wish the crop had been better, so that they could buy some of the things of which they are badly in need. The men smoke corncob pipes and talk politics. It is a cold drive home across the wind-swept prairies, but at least they have had a glimpse of a little broader and more comfortable life than that of the isolated farm. There are few social events in the life of these prairie farmers to enliven the monotony of the long winter evenings; no singing-schools, spelling-schools, debating clubs, or church gatherings. Neighborly calls are infrequent, because of the long distances which separate the farmhouses, and because, too, of the lack of homogeneity of the people. They have no common past to talk about. They were strangers to one another when they arrived in this new land, and their work and ways have not thrown them much together. Often the strangeness is intensified by the differences of national origin. There are Swedes, Norwegians, Germans, French Canadians, and perhaps even such peculiar people as Finns and Icelanders among the settlers, and the Americans come HIS 231, FL2013 10 from many different States. It is hard to establish any social bond in such a mixed population, yet one and all need social intercourse, as the thing most essential to pleasant living, after food, fuel, shelter, and clothing. An alarming amount of insanity occurs in the new prairie States among farmers and their wives. In proportion to their numbers, the Scandinavian settlers furnish the largest contingent to the asylums. The reason is not far to seek. These people came from cheery little farm villages. Life in the fatherland was hard and toilsome, but it was not lonesome. Think for a moment how great the change must be from the white-walled, red-roofed village of a Norway fjord, with its church and schoolhouse, its fishing-boats on the blue inlet, and its green mountain walls towering aloft to snow fields, to an isolated cabin on a Dakota prairie, and say if it is any wonder that so many Scandinavians lose their mental balance. [From E. V. Smalley, "The Isolation of Life on Prairie Farms," Atlantic Monthly, 72 (1893): 378–83.] ********* DOCUMENT FOR ASSIGNMENT 2 "The Treason of the Senate" (1906), David Graham Phillips Please read this document and answer the questions on the worksheet. Rhode Island is the smallest of our states in area and thirty-fourth in population—twelve hundred and fifty square miles, less than half a million people, barely seventy thousand voters with the rolls padded by the Aldrich machine. But size and numbers are nothing; it contains as many sturdy Americans proportionately as any other state. Its bad distinction of supplying the enemy with a bold leader is due to its ancient and aristocratic constitution, changed once, away back before the middle of the last century, but still an archaic document for class rule. The apportionment of legislators is such that one-eleventh of the population, and they the most ignorant and most venal, elect a majority of the legislature—which means that they elect the two United States senators. Each city and township counts as a political unit; thus, the five cities that together have two-thirds of the population are in an overwhelming minority before twenty almost vacant rural townships—their total population is not thirty-seven thousand—where the ignorance is even illiterate, where the superstition is mediaeval, where tradition and custom have made the vote an article of legitimate merchandising. The combination of bribery and party prejudice is potent everywhere; but there come crises when these fail "the interests" for the moment. No storm of popular rage, however, could unseat the senators from Rhode Island. The people of Rhode Island might, as a people and voting almost unanimously, elect a governor; but not a legislature. Bribery is a weapon forbidden those who stand for right and justice—who "fights the devil with fire" gives him choice of weapons, and must lose to him, though seeming to win. A few thousand dollars put in the experienced hands of the heelers, and the senatorial general agent of "the interests" is secure for another six years. HIS 231, FL2013 11 The Aldrich machine controls the legislature, the election boards, the courts—the entire machinery of the "republican form of government." In 1904, when Aldrich needed a legislature to reelect him for his fifth consecutive term, it is estimated that carrying the state cost about two hundred thousand dollars—a small sum, easily to be got back by a few minutes of industrious pocket-picking in Wall Street. . . . And the leader, the boss of the Senate for the past twenty years has been—Aldrich! . . . The greatest single hold of "the interests" is the fact that they are the "campaign contributors"— the men who supply the money for "keeping the party together," and for "getting out the vote." Did you ever think where the millions for watchers, spellbinders, halls, processions, posters, pamphlets, that are spent in national, state and local campaigns come from? Who pays the big election expenses of your congressman, of the men you send to the legislature to elect senators? Do you imagine those who foot those huge bills are fools? Don't you know that they make sure of getting their money back, with interest, compound upon compound? Your candidates get most of the money for their campaigns from the party committees; and the central party committee is the national committee with which congressional and state and local committees are affiliated. The bulk of the money for the "political trust" comes from "the interests." "The interests" will give only to the "political trust." And that means Aldrich and his Democratic (!) lieutenant, Gorman of Maryland, leader of the minority in the Senate. Aldrich, then, is the head of the "political trust" and Gorman is his right-hand man. When you speak of the Republican party, of the Democratic party, of the "good of the party," of the "best interests of the party;" of "wise party policy," you mean what Aldrich and Gorman, acting for their clients, deem wise and proper and "Republican" or "Democratic." . . . No railway legislation that was not either helpful to or harmless against "the interests"; no legislation on the subject of corporations that would interfere with "the interests," which use the corporate form to simplify and systematize their stealing; no legislation on the tariff question unless it secured to "the interests" full and free license to loot; no investigations of wholesale robbery or of any of the evils resulting from it—there you have in a few words the whole story of the Senate's treason under Aldrich's leadership, and of why property is concentrating in the hands of the few and the little children of the masses are being sent to toil in the darkness of mines, in the dreariness and unhealthfulness of factories instead of being sent to school; and why the great middle classÑthe old-fashioned Americans, the people with the incomes of from two thousand to fifteen thousand a year—is being swiftly crushed into dependence and the repulsive miseries of "genteel poverty." [From David Graham Phillips, "The Treason of the Senate," Cosmopolitan, April 1906, pp. 628– 38. ************** DOCUMENT FOR ASSIGNMENT 3 Keep the Consumer Dissatisfied, Charles F. Kettering (1929) HIS 231, FL2013 12 Please read this document and answer the questions on the worksheet. Not long ago one of the great bankers of the country said to me: "The trouble with you fellows is that you are all the time changing automobiles and depreciating old cars, and you are doing it at a time when people have three or four payments to make on the cars they already have. Yesterday I got an engraved invitation from one of your companies to see a new model. Out of curiosity I went. I darn near bought one. I didn't because you people wouldn't allow me enough money for my old car." A few weeks later I was again talking with this banker. He appeared to be greatly disgruntled. "I bought the new model," he barked. "But it was rotten shame that I had to accept so much depreciation on my old car. You are the fellow who is to blame. You, with all your changes and refinements, made me dissatisfied with the old model." He paused, then added, mournfully, "And that old car ran like new." I told him I thought it was worth what he paid—that is, the difference between the old and the new mode—to have his mind changed. He didn't argue over that but he did say something to the general effect that "the only reason for research is to keep your customers reasonably dissatisfied with what they already have." I might observe, here and now, that he was right. A few weeks back I was sitting with a group of executives. All were admiring a new model. "It is absolutely the best automobile that can be made," enthused one. I objected to that statement. "Let's take this automobile which, you say, is the 'best that can be made' and put it into a glass showcase," I said. "Let's put it in there—seal it so no person can possibly touch it. Just before we seal it in the case, let us mark the price in big letters inside the case." "Let us do that and come back here a year from today. After looking at it and appraising it, we will mark a price on the outside of the glass. It will be a price something less than what we think the car is worth today. Probably $200 less. Then, let's come back once every year for ten years, look through the glass, and mark a new price. At the end of ten years we won't be able to put down enough ciphers to indicate what we think of the car. That is, of course, eliminating its value as junk. HIS 231, FL2013 13 "In those ten years, no one could possibly have touched the car. There could be no lessened value through handling. The paint would be just as good as new; the crank case just as good; the real axle just as good; and the motor just as good as ever. What then, has happened to the car? "People's minds will have been changed; improvements will come in other cars; new styles will have come. What you have here today, a car that you call 'the best that can be made,' will then be useless. So it isn't the best that can be made. It may be the best you can have made and, if that is what you meant, I have no quarrel with what you said. . . ." Change, to a research engineer, is improvement. People, though don't seem to think of it in that manner. When a change is suggested they hold back and say, "What we have is all right—it does the work." Doing the work is important but doing it better is more important. The human family in industry is always looking for a park bench where it can sit down and rest. But the only park benches I know of are right in front of an undertaker's establishment. There are no places where anyone can sit and rest in an industrial situation. It is a question of change, change, change, all the time—and it is always going to be that way. It must always be that way for the world only goes along one road, the road to progress. Nations and industries that have become satisfied with themselves and their ways of doing things, don't last. While they are sitting back and admiring themselves other nations and other concerns have forgotten the looking-glasses and have been moving ahead . . . . The younger generation—and by that I mean the generation that is always coming—knows what it wants and it will get what it wants. This is what makes for change. It brings about improvements in old things and developments in new things. You can't stop people from being born. You can't stop the thing we call progress. You can't stop the thing we call change. But you can get in tune with it. Change is never waste—it is improvement, all down the line. Because I have no further need for my automobile doesn't mean that that automobile is destroyed. It goes to someone who has need for it and, to get it, he disposes of something that is unnecessary to his happiness. And so on to the end where the thing that is actually thrown away is of no further use to anyone. By this method living standards, all around, are raised. We hear people complaining because of new models in automobiles. If it were not for these new models these same people would be paying more for what they have. Recognition of the fact that progress is inevitable forces us to recognize that we must have improvements in motor cars. We, as manufacturers, must offer those improvements after they have been found to be capable improvements. The public buys and disposes of what it has. The fact that it is able to dispose of what it has enables us, as producers, to put a lower price tag on the new model. The law of economy in mass production enters here. We are permitted to turn out cars in volume because there is a market for them. HIS 231, FL2013 14 If automobile owners could not dispose of their cars to a lower buying strata they would have to wear out their cars with a consequent tremendous cutting in the yearly demand for automobiles, a certain increase in production costs, and the natural passing along of these costs to the buyer. If everyone were satisfied, no one would buy the new thing because no one would want it. The ore wouldn't be mined; timber wouldn't be cut. Almost immediately hard times would be upon us. You must accept this reasonable dissatisfaction with what you have and buy the new thing, or accept hard times. You can have your choice. [From Charles F. Kettering, "Keep the Consumer Dissatisfied," Nation's Business, 17, no. 1 (January 1929), 30–31, 79.] ******************* DOCUMENT FOR ASSIGNMENT 4 Women in War Industries Please read this document and answer the questions on the worksheet. Encouraged by government recruiting campaigns, some 6 million women took jobs in defense plants during the first three years of the war. Many of them left conventional domestic jobs— maids, cooks, waitresses—to join industrial assembly lines. Others had never worked outside the home. Not surprisingly, they encountered prejudice among their male co-workers. Yet the overall experience was quite positive for many women, and it created long-lasting changes in outlook and perspective. The two following accounts are representative of the experiences of wartime working women. Inez Sauer, Chief Clerk, Tool Room I was thirty-one when the war started and I had never worked in my life before. I had a six-yearold daughter and two boys, twelve and thirteen. We were living in Norwalk, Ohio, in a large home in which we could fit about 200 people playing bridge, and once in a while we filled it. I remember my husband saying to me, "You've lived through a depression and you weren't even aware it was here." It was true. I knew that people were without work and having a hard time, but it never seemed to affect us or our friends. They were all of the same ilk—all college people and all golfing and bridge-playing companions. I suppose you'd call it a life of ease. We always kept a live-in maid, and we never had to go without anything. Before the war my life was bridge and golf and clubs and children. . . . When the war broke out, my husband's rubber-matting business in Ohio had to close due to the war restrictions on rubber. HIS 231, FL2013 15 We also lost our live-in maid, and I could see there was no way I could possibly live the way I was accustomed to doing. So I took my children home to my parents in Seattle. The Seattle papers were full of ads for women workers needed to help the war effort. "Do your part, free a man for service." Being a D. A. R.,1 I really wanted to help the war effort. I could have worked for the Red Cross and rolled bandages, but I wanted to do something that I thought was really vital. Building bombers was, so I answered an ad for Boeing. My mother was horrified. She said no one in our family had ever worked in a factory. "You don't know what kind of people you're going to be associated with." My father was horrified too, no matter how I tried to impress on him that this was a war effort on my part. He said, "You'll never get along with the people you'll meet there." My husband thought it was utterly ridiculous. I had never worked. I didn't know how to handle money, as he put it. I was nineteen when I was married. My husband was ten years older, and he always made me feel like a child, so he didn't think I would last very long at the job, but he was wrong. They started me as a clerk in this huge tool room. I had never handled a tool in my life outside of a hammer. Some man came in and asked for a bastard file. I said to him, "If you don't control your language, you won't get any service here." I went to my supervisor and said, "You'll have to correct this man. I won't tolerate that kind of language." He laughed and laughed and said, "Don't you know what a bastard file is? It's the name of a very coarse file." He went over and took one out and showed me. * * * The first year, I worked seven days a week. We didn't have any time off. They did allow us Christmas off, but Thanksgiving we had to work. That was a hard thing to do. The children didn't understand. My mother and father didn't understand, but I worked. I think that put a little iron in my spine too. I did something that was against my grain, but I did it and I'm glad. . . . Because I was working late one night I had a chance to see President Roosevelt. They said he was coming on the swing shift, after four o'clock, so I waited to see him. They cleared out all the aisles of the main plant, and he went through in a big, open limousine. He smiled and he had his long cigarette holder, and he was very, very pleasant. "Hello there, how are you? Keep up the war effort. Oh, you women are doing a wonderful job." We were all thrilled to think the President could take time out of the war effort to visit us factory workers. It gave us a lift, and I think we worked harder. Boeing was a real education for me. It taught me a different way of life. I had never been around uneducated people before, people that worked with their hands. I was prudish and had never been with people that used coarse language. Since I hadn't worked before, I didn't know there was such a thing as the typical male ego. My contact with my first supervisor was one of animosity, in which he stated, "The happiest duty of my life will be when I say goodbye to each of you women as I usher you out the front door." I didn't understand that kind of resentment, but it was prevalent throughout the plant. Many of the men felt that no woman could come in and HIS 231, FL2013 16 run a lathe, but they did. I learned that just because you're a woman and have never worked is no reason you can't learn. The job really broadened me. I had led a very sheltered life. I had had no contact with Negroes except as maids or gardeners. My mother was a Virginian, and we were brought up to think that colored people were not of the same economic or social level. I learned differently at Boeing. I learned that because a girl is a Negro she's not necessarily a maid, and because a man is a Negro doesn't mean that all he can do is dig. In fact, I found that some of the black people I got to know there were very superior—and certainly equal to me—equal to anyone I ever knew. Before I worked at Boeing I also had had no exposure to unions. After I was there for awhile, I joined the machinists union. We had a contract dispute, and we had a one-day walkout to show Boeing our strength. We went on this march through the financial district in downtown Seattle. My mother happened to be down there seeing the president of the Seattle First National Bank at the time. Seeing this long stream of Boeing people, he interrupted her and said, "Mrs. Ely, they seem to be having a labor walkout. Let's go out and see what's going on." So my mother and a number of people from the bank walked outside to see what was happening. And we came down the middle of the street—I think there were probably five thousand of us. I saw my mother, I could recognize her—she was tall and stately—and I waved and said, "Hello, mother." That night when I got home, I thought she was never going to honor my name again. She said, "To think my daughter was marching in that labor demonstration. How could you do that to the family?" But I could see that it was a new, new world. My mother warned me when I took the job that I would never be the same. She said, "You will never want to go back to being a housewife." At that time I didn't think it would change a thing. But she was right, it definitely did. I had always been in a shell; I'd always been protected. But at Boeing I found a freedom and an independence that I had never known. After the war I could never go back to playing bridge again, being a club woman and listening to a lot of inanities when I knew there were things you could use your mind for. The war changed my life completely. I guess you could say, at thirty-one, I finally grew up. * * * Sybil Lewis, Riveter When I first arrived in Los Angeles, I began to look for a job. I decided I didn't want to do maid work anymore, so I got a job as a waitress in a small black restaurant. I was making pretty good money, more than I had in Sapulpa, Oklahoma, but I didn't like the job that much; I didn't have the knack for getting good tips. Then I saw an ad in the newspaper offering to train women for defense work. I went to Lockheed Aircraft and applied. They said they'd call me, but I never got a response, so I went back and applied again. You had to be pretty persistent. Finally they accepted me. They gave me a short training program and taught me how to rivet. Then they put me to work in the plant riveting small airplane parts, mainly gasoline tanks. HIS 231, FL2013 17 The women worked in pairs. I was the riveter and this big, strong white girl from a cotton farm in Arkansas worked as the bucker. The riveter used a gun to shoot rivets through the metal and fasten it together. The bucker used a bucking bar on the other side of the metal to smooth out the rivets. Bucking was harder than shooting rivets; it required more muscle. Riveting required more skill. I worked for a while as a riveter with this white girl when the boss came around one day and said, "We've decided to make some changes." At this point he assigned her to do the riveting and me to do the bucking. I wanted to know why. He said, "Well, we just interchange once in a while." But I was never given the riveting job back. This was the first encounter I had with segregation in California, and it didn't sit too well with me. It brought back some of my experiences in Sapulpa—you're a Negro, so you do the hard work. I wasn't failing as a rivete—in fact, the other girl learned to rivet from me—but I felt they gave me the job of bucker because I was black. . . . The war years had a tremendous impact on women. I know for myself it was the first time I had a chance to get out of the kitchen and work in industry and make a few bucks. This was something I had never dreamed would happen. In Sapulpa all that women had to look forward to was keeping house and raising families. The war years offered new possibilities. You came out to California, put on your pants, and took your lunch pail to a man's job. This was the beginning of women's feeling that they could do something more. We were trained to do this kind of work because of the war, but there was no question that this was just an interim period. We were all told that when the war was over, we would not be needed anymore. 1. Daughter of the American Revolution. [From The Homefront by Mark Jonathan Harris, Franklin D. Mitchell, and Steven J. Schechter. Copyright © 1984 by Mark Jonathan Harris, Franklin D. Mitchell, and Steven J. Schechter. Used by permission of Putman Berkley, a division of Penguin Putnam Inc.] HIS 231, FL2013 18