Talibé Children and Forced Begging in Senegal

advertisement

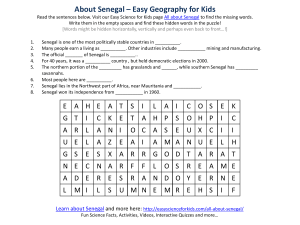

Talibé Children and Forced Begging in Senegal: A Complex Issue with a Social Norms Perspective Paper submitted as a requirement for the completion of the COURSE ON ADVANCES IN SOCIAL NORMS University of Pennsylvania - UNICEF 16 July 2012 Jennifer Keane Executive Summary Quranic schools – or daaras- were in existence before the arrival of the French in Senegal and even during the colonial period, they were the principal form of education in all but the most populous cities. The daaras in existence before French colonial rule, as those that exist today, were led by highly respected religious teachers – called marabouts - and the students were, then as now, known as talibés. In their original incarnation, daaras were based in villages and emphasis was on learning the Quran. During the harvest, the marabout and older talibés would work together in the fields to provide food for the daara for much of the year—aided by contributions from families whose talibés did not reside at the daara and from community members through almsgiving. During the 1970s and 1980s, a succession of droughts and changes in the national economy resulted in many marabouts and their pupils, or talibés, migrating from villages to cities. Unable to make use of the traditional forms of support as were available in the villages, many marabouts began forcing talibés to beg. By the 1980s, forced child begging was ubiquitous in Senegal’s cities. This practice continues today, with children being forced to beg on the streets for long hours (up to 10 hours a day) – a practice that meets the ILO’s definition of the worst form of child labour – and at the expense of their education. Children are subjected to physical and psychological abuse, particularly if they fail to bring back the daily quota of money, rice, sugar or tea set by the marabout. In many cases, the money that the children receive does not go towards operation of the daara or to meet the children’s needs and their rights to adequate food, shelter and healthcare are severely neglected. It is important to note that not all daaras in urban areas operate like this. However, at least 50,000 children attending hundreds of daaras, in Senegal are forced to beg. In Dakar alone, it was found that 95% of all child beggars were talibés, and were almost exclusively boys, the majority from poor rural areas. Qualitative studies that have been conducted in communities in rural Senegal reveal that there are diverse reasons underlying parents’ decisions to send their children to urban daaras. While poverty is a significant structural factor, the decision to send one or more children to urban daara also seems to be intertwined with strong factual and personal beliefs related to the great importance of religious education (with urban daara being the most feasible option); the desire to instill humility in children and ensure they are adequately prepared for adulthood and able to withstand future hardships; and the respected role of the marabout as religious leader and teacher. It is not entirely clear whether empirical and normative expectations exist in relation to these beliefs, but anecdotal evidence indicates that not sending a child to a Quranic school may affect the family’s social standing, and speaking out against marabouts who are mistreating children may result in social shame, threats or discrimination. Thus, it is possible that even parents who do not believe that begging is an acceptable way to instill humility and prepare children for future hardships may not object due to the respected role of the marabout. In addition, marabouts are often relatives of the family or revered members of the community, and parents may have a great deal of trust in them and perhaps do not expect that their children will greatly suffer under their care, or they may feel that while begging is not desirable it is a necessary action taken by the marabout so that he can provide for the children and ensure they receive a religious education. As noted earlier, there are plenty of daara in urban areas of Senegal that provide an adequate education for children, where they are not abused or exploited. Whether or not children beg as part of their religious education depends partly on the wealth, reputation and moral stance of the marabout. It is not entirely clear what expectations marabouts who are not practicing forced begging currently have of other marabouts. In interviews, a number of marabouts and imams have expressed indignation over the proliferation of “false marabouts” and what they perceive to be the prioritization of begging and money over the Quran in other daaras, and they are also concerned that the proliferation of forced begging will result in discrediting the practice of Quranic education within Senegalese society. However, few have been willing to publically speak out against the exploitation, push for government regulation, or bring religious institutional pressure to bear on those engaging in the practice. It would be useful to know more about these marabouts’ factual and personal normative beliefs and social expectations in relation to the conduct of other marabouts. Perhaps more importantly, it would be valuable to know more about the social expectations and potential sanctions that underpin the ‘code of silence’ that prevents taking action against the practice. It may also be useful to do a network analysis of marabouts and religious leaders, including within and across brotherhoods, to identify the most influential actors in various regions and across ethnic groups, particularly given the fact that a complex hierarchy exists among marabouts. Interventions thus far have included advocacy for legislative and policy reform and implementation, particularly of the 2005 law against forced begging and regulation of daara; social protection, particularly in the form of cash transfers to vulnerable families; modernization of daara; direct assistance to marabouts and talibes in urban areas; moving urban daara to rural villages and assistance to rural daara; and advocacy, social mobilisation and parent education. Overall, it is vitally important to maintain the focus on prevention of family separation and a systemic approach that involves social protection efforts, integrated services and access to educational opportunities. As noted earlier, however, there are many other deciding factors at play that are linked to the importance of religious education and beliefs about what this encompasses, and the important and respected role of the marabout. Thus it is important that interventions also apply a social norms perspective. It is critical to capitalize on the social norm that is in place to respect marabouts and honor their decisions, by engaging marabouts who are against the practice to work with parents and communities in speaking out and identifying other alternatives that are still in line with parents’ positive core beliefs and values, such as the importance of religious education and the desire to prepare children for adulthood and ensure that they are able to withstand future hardships in life. It is also important to frame messaging so that the practices of the exploitative marabouts do not reflect poorly on all marabouts and on their respective brotherhoods. Rather, the positive practices of the large number of marabouts who are not engaging in this practice should be emphasized to re-frame and accentuate what the desired practices of marabouts, in their role of respected teachers should be, and how this is in line with core tents of Islam and the kind of skills and ultimately the kind of lives that parents inherently desire for their children. History and Background Senegal has a population estimated at around 12 million, about 95 percent of which is Muslim. The largest ethnic groups in Senegal are the Wolof (approximately 43 percent of the population), Peuhl (24 percent), and Serer (15 percent). The form of Islam prevalent in Senegal draws heavily from Sufism. There are four principal Sufi brotherhoods or ‘orders’ in Senegal. The oldest is the Qadriyya, but the most dominant are the Tijaniyya, to which approximately half of Senegal’s Muslim population adheres, and the Muridiyya, the wealthiest and fastest-growing, followed by some 30 percent of Senegalese. The fourth order is the Layenne. Sufism is a mystical form of Islam, which grew out of distaste for materialism and finery. It places great emphasis on learning the Quran and following the guidance and example of a ‘marabout’ – a teacher or personal spiritual guide. In general, marabouts are deeply respected in Senegalese society and have great influence over their disciples, who are expected to be devoted and strictly obedient. The marabout, in turn, is expected to provide guidance throughout the disciple’s life, including during times when key decisions are made. In order to appreciate the complex factors associated with the phenomenon of talibé and forced begging, it is important to understand the origins of the practice of sending children to study at Quranic schools (or daaras) and how this has evolved over time. Quranic schools were in existence before the arrival of the French in Senegal and even during the colonial period, they were the principal form of education in all but the most populous cities.1 The daaras in existence before French colonial rule, as those that exist today, were led by marabouts, and the students were, then as now, known as talibés. While many talibés lived at home and studied at a daara in their village, many others were sent to marabouts in distant villages. The talibés lived with the marabout at the daara, often without any contact with their parents for several years. While both girls and boys undertook memorization of the Quran in their own villages, it was and remains almost exclusively boys whom parents confide to the care of marabouts. In these traditional daaras, during Senegal’s long dry season, emphasis was generally placed on Quranic studies. Then, during the harvest, the marabout and older talibés would work together in the fields to provide food for the daara for much of the year—aided by contributions from families whose talibés did not reside at the daara and from community members through almsgiving. During this period, the practice of begging existed where children lived at a residential daara and the harvest could not sustain the daara’s food needs. However, in the traditional practice, talibés generally did not beg for money; begging was solely for food and did not take time away from the talibés’ studies or put them on the street. The experience emphasized mastering the Quran and obtaining the highest attainable level of Arabic.2 In the mid to late 1800s, the French tried to regulate the daaras in order to put out of practice individual marabouts whom the French believed to be hostile to their rule. If a marabout operated a daara without authorization, he could be punished with a fine and, for the first time, imprisonment. This infuriated the population, who regarded the regulation and punishment as meddling with their religious affairs. Most children continued to attend Quranic schools and French spread slowly. Many marabouts continued to teach without authorization, and even those who had authorization generally failed to comply with official requirements3. This is a clear example of the ineffectiveness of legislation when it is too far removed from a strongly held moral or social norm. In the early 20th century, the colonial authorities changed their approach from punitive sanctions to cash payments to marabouts who set aside two hours a day for French instruction. However, in most regions, parents continued to prefer traditional Quranic schools, demonstrating how futile monetary incentives can be in changing a strongly held social norm. Throughout the entire colonial period, the traditional model of the daara remained most prevalent. During the 1970s and 1980s, a succession of droughts and changes in the national economy resulted in many marabouts and their pupils, or talibés, migrating from villages to cities. Unable to make use of the traditional forms of support as were available in the villages, many marabouts began forcing talibés to beg. By the 1980s, forced child begging was ubiquitous in Senegal’s cities, with profitability increasing the prevalence of the phenomenon. This practice continues today, with children being forced to beg on the streets for long hours (up to 10 hours a day) – a practice that meets the ILO’s definition of the worst form of child labour – and at the expense of their education. Children are subjected to physical and psychological abuse, particularly if they fail to bring back the daily quota of money, rice, sugar or tea set by the marabout. In many cases, the money that the children receive does not go towards operation of the daara or to meet the children’s needs and their rights to adequate food, shelter and healthcare are severely neglected.4 It is extremely important to note that not all daaras in urban areas operate like this. Some provide basic needs for children and ensure adequate time for education, and some marabouts live poor and ascetic lives and do not personally profit from this practice. However, at least 50,000 children attending hundreds of daaras, in Senegal are forced to beg.5 A study done by the Understanding Children’s Work partnership in 2008 found that 90 percent of child beggars in Dakar were talibé; and that 58 percent of these were from Senegal, 30 percent from Guinea Bissau, and the remainder from Guinea, The Gambia, and Mali. It also found that approximately 69 percent of begging talibés in Dakar were from the ethnic group Peuhls, with the next greatest proportion from the Wolof (25 percent). Almost all were boys, the majority were from poor rural areas and 67 percent entered the daara before age eight.6 While there are many stakeholders related to this issue, this paper will focus mainly on two groups: parents and marabouts. This paper also does not discuss all of the complex factors related to forced begging by talibés, including structural causes such as poverty and the long standing practice of confiage in West Africa. The situation in Guinea-Bissau, where a significant number of talibé originate from, is also not discussed; the focus is on Senegalese parents, children and marabouts. It should also be noted that I was only able to draw on the available literature that I could acquire within a short period (with great thanks to the UNICEF Senegal Country Office and the West and Central Africa Regional Office). The fact that I do not have direct experience in working on this issue was a significant limitation in writing the paper but learning about a new subject area was also a welcome and valued opportunity. Parents’ Beliefs and Expectations Qualitative studies that have been conducted in communities in rural Senegal reveal that there are diverse reasons underlying parents’ decisions to send their children to urban daaras. Although parents often mention poverty as a reason for sending children to Quranic schools, the decision to send one or more children to distant daara also seems to be intertwined with religious and moral norms, pedagogical beliefs, and parents’ own experience.7 I have chosen to focus on those causal factors that are not only related to poverty but also to factual and personal normative beliefs, and perhaps to social expectations and moral norms. Based on available literature, there seem to be a number of factual beliefs that motivate parents to send their children to daara. The following are just a few that seem to emerge. Religious education is extremely important for children and families to become closer to Allah, and daara in urban areas are the best options. Generally, parents view Quranic schools as important educational institutions. It is believed that by sending their child to study the Quran, God will reward them. Their religious position in relation to their local community of Muslims may also inform educational choices, as the family’s social standing may increase if their children study the Quran successfully or they have good relations with a powerful marabout.8 Parents believe that if their children study with a respected marabout, they will obtain respect and will be able to move up the social ladder and earn money by leading prayers, writing charms, and by being connected to influential networks of Islamic scholars.9 Parents are sometimes critical of the local Quranic schools and claim that the low quality of teaching makes it necessary to send children to distant daaras. Many parents also refuse to send their children to state schools due to the curriculum’s lack of Quranic instruction and the imposition of informal school fees. The appeal of state schools may have also decreased due to spending cuts, deregulation and privatisation and to young people’s difficulties finding paid employment. Generally parents would appreciate a broader education of their children, combining the study of the Quran with literacy, numeracy and other skills that enhance the children’s job prospects. Many parents carefully consider whether a child can endure the hardship of living in a daara and whether the chosen marabout has a good reputation of providing his student with opportunities for a better future.10 Thus, when parents send their children away to daara for educational purposes, it is clear that they have their best interests in mind. The personal normative belief that follows from this would then be: I should send my children to study with x marabout in x urban center. It is not clear whether empirical expectations exist (i.e. parents expect that other parents in their reference group will send their children to distant daara) or whether normative expectations may even be present (i.e. parents think that other parents and religious leaders expect them to send their children). If a normative expectation does exist, it is not clear whether a sanction for non-compliance is present, but anecdotal evidence indicates that parents’ social standing as regarded by other Muslims in their community may be influenced by their choice. It is also possible that they may not be seen as good parents who ensure that their children receive a quality education (including religious education), or they may not be seen as good Muslims who want their families and children to be closer to Allah. It would be important to know whether parents in rural Senegal would still send their children to urban daara if a Quranic school or state school of acceptable quality that integrated religious studies were available in or near their community as an alternative. Their choice could depend on a desire for the child to learn with a particular marabout who is not residing in or near their community. There also seems to be a significant value placed on distant education; through religious studies far from home, the child learns to be alone with himself and closer to God and is better prepared to withstand hardships in life on his own. While in a different context, some parents in Guinea Bissau have noted that if the child was studying close to home, he would not dedicate enough time to his studies, which is in line with the teaching of Quran on the importance of studying far away: “The Prophet Mohammed said: look for knowledge as far as China.”11 However, there is also a great deal of evidence that parents would keep their children at home if local options acceptable to them were available.12 Forced begging is an acceptable form of ‘work’ that children should endure as part of their religious education and in order to prepare them for hardships in life. When interviewed, Wolof farmers denied that that they sent their children to live with marabouts because they did not love them, could not care for them, or did not need their labor. They stated that they sent children to Quranic schools due to spiritual, educational and moral considerations. They relayed that they waived their own needs for their sons’ labour to demonstrate their membership in Islam, hoping that the discipline in the Daara would mould their sons’ character and help them to withstand difficulties in life.13 Many families who were interviewed by Human Rights Watch knew that their children begged long hours, but justified it as necessary for the marabout to survive and pay rent. In a recent study in Kolda region, 30 percent of families who had entrusted a child with a marabout believed that living conditions at the daara were indeed harsher for the child than those at home.14 It is important to realise that parent’s acceptance of different forms of suffering must be understood in the local context. For some parents, urban and rural daaras are similar and the only difference is that urban talibés’ ‘farm’ is the street and their ‘crop’ is money instead of groundnuts. Thus, they may not necessarily be concerned that their children spend more of the day working than studying. Western concepts of ‘childhood’ and ‘child rearing’ and characteristics that signify that a child is ‘doing well’ may thus be quite different from local perceptions.15 However, the acceptance by parents of forced begging and harsh discipline also varies. Some fathers have themselves undergone severe hardship in Quranic schools in the past but are not deterred from sending their sons to a marabout (thus, they are influenced by a certain schema that they have grown up with).16 Harsh discipline may also take place in local schools or in state schools, or even in some homes, and may not be seen as anything out of the ordinary. In contrast, other parents from rural Senegal stated that they that they began to send their sons to new Arabic schools (medersas) in their communities, which are said to be less exploitative, because they did not wish to subject the boys to the same hardships that they had endured in their own childhood.17 Qualitative studies have also revealed that when severe abuse of the children by marabouts is revealed to parents, some are shocked and remove the children, while others choose to send the children back to the marabout, even when they have run away from the daara.18 The decision to return them (as the decision to send them in the first place) may be based on a variety of factors ranging from the economic to religious to social. Anecdotal evidence has shown that when some children return home without having learned the Quran, it is also a source of shame for the parents. While it is not clear whether empirical or normative expectations exist and thus whether tolerance of forced begging is a social norm, it does seem likely that the belief is grounded in the broader moral norm of enduring suffering to gain humility and become closer to Allah. The marabout knows what is best for the well-being of children and for their religious and spiritual development. Acceptance of harsh treatment may also be due to the high level of respect given to marabouts, which may result in a reluctance to criticize them, as they are seen as authoritative religious figures and are often an elder, respected relative or community member.19 Moreover, in West Africa, a child’s socialisation and child rearing is seen as the responsibility of the extended family and community. This may also be an underlying reason why parents instil so much trust in marabouts, as many are often related or are close to the families. Thus, some parents may not anticipate that their children would be treated in such a way. Some may also not believe in forced begging as a form of ‘work’ that children need to endure, but if they believe that the marabout knows what is best for their child’s religious and spiritual development and normative and empirical expectations are in place (as discussed below), this may result in a conditional preference of sending the child to the marabout despite the inconsistency with their own factual and personal normative beliefs. In interviews with Human Rights Watch, some parents stated that the marabout “demanded” the child, and that since the marabout was an authority figure— often an elder, respected relative or community member—they “could not say no.”20 It is not clear whether empirical and normative expectations exist (i.e. whether parents expect others to similarly trust and respect the marabout and whether they believe that other parents except them to do the same). Based on available literature, it would seem likely that these expectations are indeed in place, particularly because of ingrained respect for marabouts based on their role as spiritual guides that dates back hundreds of years. The sanction for overtly not trusting and/or respecting a marabout seems to be social shame, threats and/or discrimination. For example, one man who filed charges after his son was brutally beaten by a marabout was shunned by his village and his own father, who told an Associated Press journalist: “[The beating] was an accident and my son had no right to humiliate the marabout.... The day they took the marabout to prison, it hurt me so much it was as if they had come to jail me.”21 (While this example shows that in this case, social sanctions were in place, it should also be noted that despite the sanctions that the father probably anticipated, he was still willing to report the marabout). An individual who runs a center for talibés in Mbour described how she faced threats and ostracism from marabouts and the local community for trying to press charges regarding the rape of a young talibé.22 Thus, it would be useful to know more about the personal normative beliefs of parents who are aware of the treatment that their children experience under care of the marabout, i.e. whether they believe that children should receive this treatment as part of their religious education or whether they do not believe this, but they observe other parents tolerating it and believe that they too are expected to tolerate it (particularly due to the implicit disrespect for marabouts that non-tolerance may suggest). Marabouts’ Beliefs and Expectations As noted earlier, there are plenty of daara in urban areas of Senegal that provide an adequate education for children, where they are not abused or exploited. Whether or not children beg as part of their religious education depends partly on the wealth, reputation and moral stance of the marabout.23 It is not entirely clear what expectations marabouts who are not practicing forced begging currently have of other marabouts. As revealed in qualitative research, a number of marabouts and imams have expressed indignation over the proliferation of “false marabouts” and what they perceive to be the prioritization of begging and money over the Quran in other daaras. They are also concerned that the proliferation of forced begging will result in discrediting the practice of Quranic education within Senegalese society. However, few have been willing to publically speak out against the exploitation, push for government regulation, or bring religious institutional pressure to bear on those engaging in the practice.24 It would be useful to know more about these marabouts’ factual and personal normative beliefs and social expectations in relation to the conduct of other marabouts. Perhaps even more importantly, it would be useful to know marabouts’ beliefs and social expectations about criticizing the actions of other marabouts. Perhaps marabouts do not want to speak out against others because it may reflect badly on the brotherhood and/or they may be sanctioned by other marabouts, or followers of the brotherhood. Some degree of pluralistic ignorance may even be in place. A greater understanding of the beliefs, expectations and possible sanctions that underlie the apparent ‘code of silence’ around the abuses committed by ‘false marabouts’ may yield insights into how other marabouts who are against the practice could be better engaged to support its elimination. It would also be interesting to know more about the factual and personal normative beliefs of marabouts who force children to beg and do not provide them with adequate care and education, i.e. if they still believe they are doing the right thing because they are instilling humility in the children and preparing them for hardships later in life, and whether they believe they are expected to do this. In interviews with Human Rights Watch, a majority of marabouts claimed that begging is important for the talibés’ moral education, particularly to teach humility. However, from the same Human Rights Watch study, three times as many talibés said that their marabout’s own children did not beg as those who said that they did, and it has been noted that this justification does not hold up when it is clear that other marabouts in the same urban areas do not engage in this practice. Marabouts also claim that children need to beg in order to cover food and housing costs, but from interviews done with talibés, the money collected often does not go towards their food and housing. It should not be assumed that all marabouts who force children to beg have the same motivations – while it is clear that some personally profit from exploitation of the talibés, others do lead ascetic lives. II. Interventions Thus Far The following is a cursory analysis of the main interventions that have been implemented thus far by UNICEF and/or NGOs to address the issue of forced begging by talibé. (As noted earlier, this is solely based on available documentation since I am not working on this issue or based in Senegal). Advocacy for legislative reform and implementation The Senegalese government has defined forced begging as a worst form of child labor and in 2005, it criminalized forcing another into begging for economic gain.i However, the legislation is hardly implemented. Five years after it was passed, no government official interviewed by Human Rights Watch could identify a case when the law was applied to sanction a marabout solely for the practice of forced begging and marabouts implicated in abuse and neglect have not been investigated or held accountable.25 This lack of enforcement can be explained by the reluctance of the population and government leaders to express any opposition to religious leaders. There are political reasons why the government is reluctant to enforce the legislation, namely fear of political backlash by the religious brotherhoods. As stated by one government official, “The state has made efforts, but is very sensitive to the issue, particularly in terms of punishment. The grand marabouts—the leaders of the brotherhoods—this involves them, even if indirectly. If you touch any of the marabouts, you touch the brotherhoods, and that is very difficult here. You lose votes, maybe you lose office, and you face trouble.26” However, an underlying reason for lack of enforcement is also that the legislation and related policies are too far from the current moral and social norms to be effectively implementedii. It was interesting to note the recommendation of a Senegalese assemblywoman that the state could hold accountable the most exploitative or abusive marabouts through imprisonment and fines, and use alternative sanctions like public shaming for others (i.e. adjust punitive sanctions and implement them progressively). However, even this would appear to be challenging for reasons outlined above. In addition, punishment may even lead to retaliation if it is viewed as a hostile or unfair act. Given the history of perceived interference by French colonialists in religious affairs, attempts to enforce the i The 'Law to Combat Trafficking in Persons and Related Practices and to Protect Victims' of 2005 devotes a section to forced begging and the vulnerability of children. Accordingly anyone found guilty of organising or pressuring another person to beg can be fined Tor imprisoned. ii This assumes, as stated above, that social norms related to respect for marabouts and tolerance of forced begging as a form of ‘work’ and discipline are in place. Some government officials may even believe that marabouts should ultimately be respected, and this may also contribute to lack of enforcement. legislation may be interpreted as attempts to subvert the power of religious authorities. Explaining why the government has been slow to regulate Quranic schools following its official recognition of them in 2010, a high level official in the Ministry of Family stated, “It is impossible for the state to regulate immediately. It must first gain the marabouts’ trust…”27 This reinforces the importance of establishment of trust among all actors involved before changes in a practice can be made a reality. While advocacy for enforcement of legislation is certainly critical, this needs to be coupled with a deeper understanding of the normative beliefs and social expectations that are in place which may be impeding effective implementation. Social protection With the support of village councils, a model of cash transfers to families with children at risk of begging was launched in the departments of Kolda and Coumbacara, benefiting 900 households and in 2012, cash transfers will be provided in 35 villages.28 As many parents have cited poverty as one of the reasons for sending their children to urban daara, cash transfers constitute an important prevention mechanism. However, unless other motivating factors are addressed, including those related to the beliefs and potential social expectations outlined above, parents may still be motivated to send their children to urban daara where they may be at risk of abuse and exploitation. In addition, and as noted above, some parents have claimed that economic factors are not a main motivation – rather they are sacrificing the productive labour of their sons on their farms so that they can receive a religious education under the marabout, and this sacrifice brings their families even closer to Allah. Thus, any social protection interventions need to be accompanied by an understanding of the beliefs and social expectations that motivate parents to send their children to urban daara, which may go beyond poverty. Modernization of daara In recognition of the fact that many parents do not want to send their children to state schools due to lack of Quranic instruction, in 2004 the government amended the education law to allow for religious instruction in state schools. The government has also built state-funded “modern” daaras in which Quranic studies are combined with Arabic, French, and subjects such as mathematics and science. 100 modern daaras will be built by the end of 2012 and each will accommodate around 300 students. Begging for money is generally not performed, as the modern daaras are often financed by inscription fees, religious authorities, the state, foreign aid, and humanitarian aid agencies. The schools will also be subjected to inspection by state officials and, if they fail to meet standards, can be ordered to close. . This is a positive initiative and will certainly meet the needs of some parents and children, and can help to change the factual belief that Quranic schools in urban areas are the best educational option for children by providing an alternative. However, with an estimated 50,000 talibé who are currently forced to beg in urban centers in Senegal, it may take a long time to modernize enough daaras to meet the needs of all children and families. In addition, marabouts apply for their daaras to be ‘modernized’ and if their projected gains from forced begging are much higher than state teachers’ salaries, some may be unlikely to apply. Direct assistance to marabouts in urban areas and talibés Dozens of national and international humanitarian aid organizations in Senegal provide a range of services to assist talibés and improve conditions in daaras. This includes provision of mats for sleeping; water; clothing and shoes; construction of shelters; food; bath soap, laundry detergent, and disinfectant; medicines or healthcare assistance; French classes; money to satisfy the talibés quota; microcredit loans to marabouts to start businesses; and payment of the marabout’s rent. However, this has created a “pull effect”, inadvertently incentivizing marabouts to move from rural villages to urban areas where many aid agencies’ efforts are focused and begging is prevalent. In addition, many marabouts who receive assistance do not adjust begging practices but benefit from the additional income. Funds given to marabouts are not always adequately monitored and marabouts are often not held accountable for how the funds are used. 29 UNICEF does not support these types of interventions and does not directly assist urban daaras but most humanitarian organisations have not followed suit. It needs to be ensured that assistance is not incentivizing further family separation and exploitation of children. The use of incentives can seriously backfire if not accompanied by an analysis of motivating factors. Some organisations also provide direct support to talibés in the form of drop in centers, shelters and hotlines, and in some cases, ‘godmothers’ are identified who can provide meals, clothes and other needs for talibé children. However, this may also create a “pull factor” with parents sending children to urban centers with the expectation that even if they are not treated so favourably at daara, they can find support elsewhere. It also does not address the root causes of the problem, including normative beliefs and social expectations of parents who send their children to urban daara and the ‘code of silence’ that exists and prevents speaking out against harmful practices committed by marabout. While it supports the immediate needs of children, it ignores the role of the marabout altogether, and there is a risk that it may inadvertently help some marabout to further profit from exploiting children. Moving urban daara to rural villages and assistance to rural daara Rather than supporting urban daara, UNICEF along with Terre des Hommes and Intermonde have assisted the Ministry of Family to relocate several urban daaras to villages. Other groups, like ONG Gounass and Tostan, assist village daaras in particular or community development more generally and encourage marabouts and families to keep children in their villages. These are extremely important preventative measures and it will be important to determine their impact and learn from them. Advocacy, social mobilisation and parent education UNICEF has strengthened ties with religious congregations (networks of Imams and Ulemas, Catholic Church), media (print, radio and television) and the Partnership for the Withdrawal and Reinsertion of Street Children (PARRER) for the implementation of a strategy on advocacy and communication on social change, especially against begging and FGC.30 From available documentation, it is not entirely clear what this strategy encompasses, but it would be important that it is grounded in a solid understanding of the motivating factors, including factual and normative beliefs and social expectations, of parents who send their children to urban daara and the factual and normative beliefs and social expectations of marabout with respect to forced begging and underlying norms that may prevent or support speaking out against marabouts who are exploiting and abusing talibés. Perhaps messaging could build upon positive social or moral norms that exist, such as those that relate to parents’ desires to provide a quality religious education for their children and ensure that children are prepared for adulthood and able to withstand hardships later in life. Parent education should focus not just on abuses that talibé experience at the hands of exploitative marabout, but on alternatives (defined by parents and communities) that could better meet their objectives of ensuring that their children grow stronger in their Islamic faith, are spiritually grounded and are well-equipped for challenges that lie ahead. This would most likely require open discussion and deliberation among parents, marabout, other religious and community leaders, as well as children in order to ensure that their perspectives are also considered. Given prevailing norms related to respect and authority of marabout, their engagement and that of other religious leaders is critical. In 2010, Tostan introduced the Child Protection Module as a new addition to the organization’s human rights-based education program, the Community Empowerment Program (CEP). This innovation grew out of the earlier Talibé Project and benefits from the insight and lessons learned from the project evaluation. This module was created to be a special training for Community Management Committees (CMCs), which are established by each of Tostan’s partner communities to organize and lead the community’s development initiatives. The module serves as the launching point for the establishment of Commissions for Child Protection (CCPs) within the CMCs. These CCPs then take responsibility for leading the community’s advocacy and actions to protect children’s rights and transform the existing social norms that sustain harmful practices. In addition to leading these community-wide projects, the CCPs can also intervene directly in cases of child abuse. Tostan is currently implementing the Child Protection Module in four regions across Senegal with 64 villages that have previously completed the Community Empowerment Program (CEP). The module is designed to reinforce the capacity of communities to identify situations or practices that place children at risk; to help them prevent and address the trafficking or migration of children to urban centers; to assist children faced with challenges such as sexual abuse, incest, forced marriage, or female genital cutting (FGC); and to build strong, dynamic structures through the CCPs that will ensure the long-term protection of children.31 Further information was not publicly available on this project, but it would be interesting to learn more about the social norms that are being addressed and how the CCPs are functioning. It is hoped that lessons learned from support to Child Protection Committees in other countries are also being integrated into the programme (i.e. the need to build on already existing mechanisms, risk of committees being viewed as policing forces which can create backlash, burden of additional responsibilities without adequate training or requisite services in place, lack of clearly defined roles, etc.) It would also be interesting to know if this project involves marabouts and other religious leaders, given the key role they would need to play in promoting changes in social norms and changing practices. III. Suggestions with a Social Norms Perspective The issue of talibé and forced begging in Senegal is extremely complex with many underlying and inter-linked causal factors that range from structural to economic to political to social – and many of these were not covered in this paper. However, based on the above analysis, the following are some suggestions with a social norms perspective. On the whole, the interventions that are attempting to address structural causes such as poverty as well as lack of access to educational opportunities are extremely important and vital for prevention of family separation. As noted earlier, however, there are many other deciding factors at play that are linked to the importance of religious education and beliefs about what this encompasses, and the important and respected role of the marabout. In order to address abuse and exploitation of talibés in a sustainable way, it is extremely important to better understand parents’ motivations for sending their children to study at urban daaras. It seems that in many cases, the motivations are not just related to poverty but are intertwined with moral norms and deeply ingrained personal normative beliefs that may be reinforced by social expectations. A greater understanding of the factors behind parents’ choice of marabout and daara may be useful (including how this varies across geographical areas and ethnic groups) in order to ensure that adequate alternatives are in place for parents, which support existing positive beliefs and positive social norms, prevent children from being sent into or returned to situations that may be exploitative, and prevent unnecessary separation of children from their families. It was found that in Dakar, for example, 69% of talibés were from the Peuhl (“Fulani”) ethnic group. There is evidence that the reason for the high number of talibé begging in Senegal from this group is due in part to an internal conflict between the two main Fula groups in Guinea- Bissau, the Futa Fula and the Fula of Guinea-Bissauiii and a history of marginalization. It would be useful to know more about whether factors for choosing marabout and darras differ among ethnic groups residing in Senegal. It would also be useful to know whether motivating factors differ among parents who belong to different brotherhoods or ‘orders’ of Sufism. It is clear that parents send their children away with their best interests in mind. Their core beliefs about the need to provide them with a good religious education and the need to ensure that they are prepared for and able to withstand future hardships in life are indeed beliefs of parents who want the best for their children. It is important to recognize and build on these positive core beliefs. Through discussion and deliberation involving parents, marabout and other religious leaders, children and community leaders, perhaps it could be realized that the experiences of many talibé children are inconsistent with these core beliefs and values, and positive alternativesiv to sending children to distant daara could be identified. (This could also be an entry point to a) discussions around the importance of keeping children within families, building on argumentation that has been developed by Islamic scholars on the important role of parents in the education of children as future Muslims, and b) on children’s right to protection more broadly, in order to also help ensure that children who attend rural daaras are also not forced to work in the fields for long hours at the expense of their education and health). As mentioned, the role of marabout and religious leaders in these discussions is crucial. Tostan’s Community Empowerment Programme, including introduction of a Child Protection Module, seems to support such public discussions. The role of marabouts and religious leaders is crucial for even being able to begin such debates, and it would be important to know how involved they have been in the Tostan project. It would also be interesting to know whether all the work that Tostan has been supporting on elimination of FGC (including community deliberations, organized diffusion, etc.) is having any impact in those communities on other protection issues, including keeping children within families, or at least preventing them from being sent to daaras where they may be abused and exploited. As noted numerous times in available literature, there are often parents in communities who do not agree with sending children to urban daara or with the harsh treatment by some marabout. These parents could perhaps be identified and could constitute a core group that could support the deliberations in communities, along with religious leaders. A network analysis across ethnic groups and by membership in brotherhoods could also help to identify how various parents and communities are influenced by one another and how they are influenced by marabout and other religious actors. The role of marabout and other religious leaders’ roles in building religious discourse against child begging is obviously critical, and this has already been widely recognized by UNICEF and others. As expressed by one Senegalese humanitarian worker, “If leaders of the two great brotherhoods in Senegal said ‘no more forced child begging,’ there would be no more forced begging.”32 iii The Fula in Guinea Bissau can be divided into two main groups: the Fula of Guinea-Bissau and the Futa-Fula, who entered the area from Guinea, and whose members traditionally belong to the religious elite. In discussions with many people, suspicion and mistrust between these different groups emerged over the issue of religious studies. Recently an increasing number of the Fula of Guinea-Bissau, who have completed studies in the Futa Tooro area in Senegal, have begun to act as religious leaders and marabouts in their communities in Guinea-Bissau. Because their community members are not accustomed to begging, the marabouts take their students to Senegal where they maintain their schools through begging. As an expression of cultural resistance, they ignore existing religious Koranic schools as respected educational centres. (See Einarsdóttir (2010) for more information). iv It is of course important to note that the possibility of positive alternatives is essential and thus the ongoing work related to social protection and improving access to educational opportunities is crucial. A better understanding of the personal normative beliefs and social expectations of marabouts with respect to forced begging and the beliefs and expectations that perpetuate the ‘code of silence’ around speaking out against the practice, would perhaps enable more meaningful engagement with marabouts and religious leaders who have not made their opposition explicit. Perhaps a core group of marabouts and religious leaders who are against the practice could be further identified and engaged. However, it would be important that they do not feel that speaking out will jeopardize their respected positions or damage the reputation and standing of their respective brotherhoods. Thus, it may be important that their interventions are made in parallel with burgeoning resistance that has been observed from Senegalese civil society, and perhaps in coordination with core groups of parents that could be identified, as noted above. It may also be useful to ‘re-categorize’ the problem, i.e. instead of focusing on ‘false marabouts’ as criminals, it could be highlighted how the practice of forced begging is against core Islamic tenets which so many other marabouts in the brotherhoods do support and exemplify. This could perhaps support the creation of a new social norm against forced begging. In order to build trust between key religious actors and the government, perhaps marabouts and community members could be involved in monitoring daara to ensure that children are not being abused or exploited, are adequately cared for and are receiving a quality education, and the concept of positive competition and rewards could be put in place for daara that adhere to standards. If key religious actors were to publicly speak out against forced begging (i.e. the practice itself and not the particular marabouts), then perhaps the shame of running an exploitative daara would be greater than the monetary incentive for marabouts to continue with the practice. A network analysis of marabouts and religious leaders, including within and across brotherhoods, would also be extremely useful to identify the most influential actors in various regions (with respect to influence on parents and communities but also on other marabouts), particularly given the fact that a complex hierarchy exists among marabouts. It would also be important to further explore the role of alms giving and how a moral obligation to give alms can possibly be channelled in a positive way to support prevention efforts, as in the past communities gave alms to support daaras in villages. Overall, it is important to maintain the focus on prevention of family separation and a systemic approach that involves social protection efforts, integrated services and access to educational opportunities but to also ensure that interventions apply a social norms perspective. It is critical to capitalize on the social norm that is in place to respect marabouts and honor their decisions, by engaging marabouts who are against the practice to work with parents and communities in speaking out and identifying other alternatives. It is also important to frame messaging so that the practices of the exploitative marabouts do not reflect badly on all marabouts and on their respective brotherhoods. Rather, the positive practices of the large number of marabouts who are not engaging in this practice should be emphasized to re-frame and accentuate what the desired practices of marabouts, in their role of respected teachers should be, and how this is in line with core tents of Islam and the kind of skills and ultimately the kind of lives that parents inherently want for their children. Collaboration with the Guinea Bissau office to address movement of children from GuineaBissau to Senegal has been underway and is essential. Perhaps cooperation to address similar underlying moral and social norms could also be established. Finally, it would be extremely important to document the effectiveness of interventions (both those related to addressing structural factors and those more related to the social norms perspective) in order to determine the package of interventions that can have the most significant impact in ending the practice of forced begging and ensuring children’s right to a protective family environment. 1 Human Rights Watch (2010) ‘Off the backs of the children’. Forced begging and other abuses against Talibés in Senegal. New York: Human Rights Watch. 2 Ibid. 3 Ibid. 4 Ibid. 5 Ibid. 6 UCW (2007) Enfants mendicants dans la region de Dakar. Understanding Children’s Work Project Working Paper Series, 92 p 7 Thorsen, Dorte (April 2012) Children Begging for Qur’ānic School Masters: Evidence from West and Central Africa. UNICEF Briefing Paper No. 5. Dakar: UNICEF. 8 Einarsdóttir, J., Boiro, H., Geirsson, G. & Gunnlaugsson, G. (2010) Child trafficking in Guinea. An explorative study. Reykjavik: UNICEF Iceland. 9 Perry, D.L. (2004) Muslim child disciples, global civil society, and children's rights in Senegal: The discourses of strategic structuralism. Anthropological Quarterly, 77(1): 47-86; Şaul, M. (1984) The Quranic school farm and child labour in Upper Volta. Africa, 54, 71-87. 10 Ibid. 11 Einarsdóttir, J., Boiro, H., Geirsson, G. & Gunnlaugsson, G. (2010) Child trafficking in Guinea. An explorative study. Reykjavik: UNICEF Iceland. 12 Einarsdóttir, J., Boiro, H., Geirsson, G. & Gunnlaugsson, G. (2010) Child trafficking in Guinea. An explorative study. Reykjavik: UNICEF Iceland; Human Rights Watch (2010) ‘Off the backs of the children’. Forced begging and other abuses against Talibés in Senegal. New York: Human Rights Watch; Thorsen, Dorte (April 2012) Children Begging for Qur’ānic School Masters: Evidence from West and Central Africa. UNICEF Briefing Paper No. 5. Dakar: UNICEF. 13 Perry, D.L. (2004) Muslim child disciples, global civil society, and children's rights in Senegal: The discourses of strategic structuralism. Anthropological Quarterly, 77(1): 47-86; Şaul, M. (1984) The Quranic school farm and child labour in Upper Volta. Africa, 54, 71-87. 14 Human Rights Watch (2010) ‘Off the backs of the children’. Forced begging and other abuses against Talibés in Senegal. New York: Human Rights Watch. 15 Mbow, P. (2009) Secularism, religious education, and human rights in Senegal. Working Paper No. 09-007, Institute for the Study of Islamic thought in Africa (ISITA), Northwestern University; Perry, D.L. (2004) Muslim child disciples, global civil society, and children's rights in Senegal: The discourses of strategic structuralism. Anthropological Quarterly, 77(1): 47-86; Şaul, M. (1984) The Quranic school farm and child labour in Upper Volta. Africa, 54, 71-87. 16 Perry, D.L. (2004) Muslim child disciples, global civil society, and children's rights in Senegal: The discourses of strategic structuralism. Anthropological Quarterly, 77(1): 47-86; Şaul, M. (1984) The Quranic school farm and child labour in Upper Volta. Africa, 54, 71-87. 17 Ibid. 18 Human Rights Watch (2010) ‘Off the backs of the children’. Forced begging and other abuses against Talibés in Senegal. New York: Human Rights Watch. 19 Ibid; CRDH-Tostan (2010) La mendicité des "talibés" en milieu rural sénégalasis: résultats d'une étude exploratoire (Régions de Tambacounda et de Kolda, 2010). Centre de Recherche pour le Développement Humain (CRDH) et Tostan, Dakar. 20 Human Rights Watch (2010) ‘Off the backs of the children’. Forced begging and other abuses against Talibés in Senegal. New York: Human Rights Watch. 21 Ibid. 22 Ibid. 23 Thorsen, Dorte (April 2012) Children Begging for Qur’ānic School Masters: Evidence from West and Central Africa. UNICEF Briefing Paper No. 5. Dakar: UNICEF. 24 Human Rights Watch (2010) ‘Off the backs of the children’. Forced begging and other abuses against Talibés in Senegal. New York: Human Rights Watch. 25 Ibid. 26 Ibid. 27 Ibid. 28 UNICEF Senegal Annual Report 2011 (UNICEF Intranet). 29 Human Rights Watch (2010) ‘Off the backs of the children’. Forced begging and other abuses against Talibés in Senegal. New York: Human Rights Watch. 30 UNICEF Senegal Annual Report 2011 (UNICEF Intranet). 31 http://www.tostan.org/web/page/870/sectionid/547/pagelevel/3/interior.asp 32 Human Rights Watch (2010) ‘Off the backs of the children’. Forced begging and other abuses against Talibés in Senegal. New York: Human Rights Watch.