Simplization of the Austrian School theories on capital theory and

advertisement

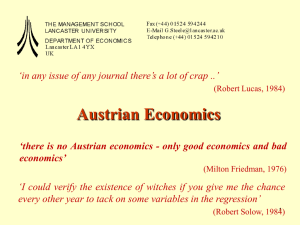

Overview of the Austrian School theories of capital and business cycles and implications for agent-based modeling Presentation to New School for Social Research Seminar in Economic Theory and Modeling For more information see cameroneconomics.com Background and Motivation The “Austrian School of Economics” lost its prominence in the 1930s with the rise of Keynesian economics. One of the reasons for this (see Hayek 1995) is that Austrian School macroeconomic theory could not be adequately formalized with mathematics, as was done with John Maynard Keynes's ideas from the General Theory. When F.A. Hayek won the Nobel Prize in 1973 this created a resurgence of interest in the ideas of the Austrian School. Our research is a further continuation of this resurgence in Austrian School ideas. Generalized Notes on the “Austrian School of Economics” 1) The Austrian School is not an argument for laissez-faire capitalism. (Hayek believed in the negative income tax, and, that many institutions belonged in society because they evolved into society, and thus exist for a reason.) 2) The Austrian School can be seen as a methodology approach which is wary of the unintended consequences of government intervention and its effect on the price system which is seen as the coordinating factor in a society’s economy. 3) The Austrian School methodology prioritizes logical reasoning over empirical relationships because it assumes the economy is too complex to model causality. 4) The Austrian School uses the individual as entrepreneur as basis for analytical approach and the subjectivity of decision-making. It is thus skeptical of the validity of other economic schools of thought, especially those using generalized aggregations. 5) Hayek later in life lost faith in general equilibrium theory, thus agentbased modeling might be valid method to evaluate some Austrian School concepts. Hayek uses a triangle to graphical represent an economy and the disaggregated, simultaneous, heterogeneous capitals in an economy (the capital structure of an economy). . . Bohm-Bawerk alone among the Austrians wanted to aggregate capital into an “average period of production.” We have formalized this concept by making the average period of production as given by at Capital Index (K), and Where i = (1, 2, …, k), k is equal to the number of the highest stage of production in the economy (in our model k = 5, where five represents the mining stage of production); x is each stage of production, and w is the weight of the production stage’s quantity of capital in relation to the quantity of capital in the economy as a whole. In this economy, K = .4(1) + .25(2) + .20(3) + .10(4) + .05(5) = 2.15. Austrian School capital theory assumes natural or normal rates of interest under which an economy (society as living organism) creates a natural capital structure, which in turn provides for, under the ‘animal spirits’ of human action and creativity, capital accumulation, economic growth and increasing standards of living. The theory of natural rates of interest (matching the endogenous preferences of savers and borrowers) assumes also that an economy experiences natural business cycles (or “colds” in biological terms) the downturns of which are overcome over time by the ‘animal spirits’ of human action. It is only when external bodies enter the natural economy (in this case monetary policy interest rate manipulations) that the natural capital structure is upset, creating incentives which cause malinvestment in unsustainable, longer stages of production and, due to the opportunity costs of scarce resources, reduced consumption. Malinvestment prolongs a natural economic downturn and associated unemployment because the sticky over-investment in unproductive sectors needs to be “worked-out” (or in biological terms, cleansed) from the system. This cleansing process takes longer than if there had not been unnatural malinvestment. It is when “unhealthy” investment is purged from the economy that healthy investment and (sustainable) economic development continues based on subjective tastes and risk preferences of society’s individual entrepreneurial actors. Austrian School capital theory is based on simultaneous, heterogeneous, capitals, each with a unique level of risk. Note that the alpha risk measure is actually a proxy for market uncertainty, the technology, the regulatory environment, the labor pool, the climate and/or resource dependency, the competitive factors, ‘rational expectations’ based on limited information, and local knowledge surrounding the investment in the stage of production as envisioned by the entrepreneur. Alpha i, therefore, of course, varies with the subjective knowledge of each entrepreneur. Here is a graphical-analogical model example of creative destruction. Let’s assume a technology shock which effects alpha 3, what is the result of productivity, employment and investment in this and other stages of production? Austrian Capital Theory and Agent-Based Modeling The Basic Model: Models subjective unique risk preferences generalized into three classes, with bounded, “sticky”, investment functions based on time lags for investment to move from one stage of production to another. Unemployment based on investment time-lags, with lay-offs beginning at higher stages of production. Economy operates over-time showing results on accumulation, distribution, growth, employment and population. • Starts with three ‘classes”, 1) rich start with 2 capital units, earn investment returns only and are more risk seeking than middleclass, 2) middleclass start with one capital unit, earn both wage income and investment returns, and 3) poor earn wages only. •Assumes all wages spent. •Capital hires wages. Each capital worker unit initially allocated in economy according to weight of stage of production in capital structure of economy. •Poor moves to middle class after 20 periods of work; when poor moves to middleclass another poor is born. Each agent lives 40 years. •Middleclass moves to rich after accumulating second capital unit. •Interest rate change takes three periods , moving from lower to higher stages of production, before fully integrated into investment decisions. • Model allows for varying endowments , and risk preferences, within classes. For Further Reference Bohm-Bawerk, Eugen. 1891. The Positive Theory of Capital. London: Macmillan and Co. Garrison, Roger. 2001. Time and Money: the Macroeconomics of Capital Structure. New York: Routledge. Garrison, Roger. 2007. “Capital-Based Macroeconomics,” on-line slide show, http://www.slideshare.net/fredypariapaza/capitalbasedmacroeconomics, accessed 10/6/07. Hayek, Friedrich A. [1931] 1966a. Prices and Production. New York: Augustus M. Kelley Publishers. Hayek, Friedrich A. [1933] 1966b. Monetary Theory and the Trade Cycle. New York: Augustus M. Kelley. Hayek, Friedrich A. 1995. Contra Keynes and Cambridge: Essays, Correspondence. Edited by Bruce Caldwell. Chicago: University of Chicago. Hoppe, Hans-Hermann. 1993. The Economics and Ethics of Private Property. Boston: Kluwer Academic. Keynes, John M. 1931. “The Pure Theory of Money. A Reply to Dr. Hayek.” Economica (11) 34, 387-397. Kurz, Heinz D. 1990. Capital, Distribution and Effective Demand: Studies in the “Classical Approach” to Economic Theory. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press. Kurz, Heinz and Salvadori, Neri. 1992. Theory of Production I. Milan: Instituto di ricera sulla Dinamica dei Sistemi Economoci (IDSE). Menger, Carl. [1871] 1950. Principles of Economics. Glencoe, IL: Free Press. Mises, Ludwig. [1932] 1990. “The Non-Neutrality of Money”, in Money, Method and the Market Process, Richard M. Ebeling, ed., from lecture given to New York City Economics Club. Norwell, MA: Kluwer Academic Publishers. Mulligan, Robert F. 2006. “An Empirical Examination of Austrian Business Cycle Theory.” Quarterly Journal of Austrian Economics 9 (2), 69-93. Schumpeter, Joseph R. 1950. Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy. New York: Harper & Row.