Essays schizophrenia

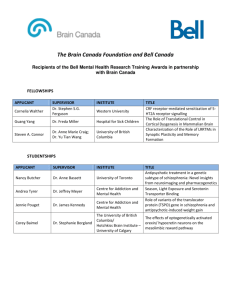

advertisement

Discuss issues associated with the classification and/or diagnosis of schizophrenia (8+16 marks) The issues surrounding the diagnosis of schizophrenia focus on reliability and validity. Reliability is related to consistency in diagnosis whereas validity is concerned with accuracy. The two diagnostic tools used for schizophrenia are the ICD and the DSM and they have key differences. The DSM is a tool that was created by Americans for Americans, although is used in some parts of Europe as well. On the other hand, the ICD was created by the World Health Organisation which is made up of representatives from 193 countries. The DSM, compared to the ICD, could therefore be questioned in its validity, particular in terms of population validity, as it is culturally biased and may not be able to relate to other cultures. This is important as there may be cultural differences in interpretation of symptoms, for example, hearing voices in some cultures is considered to be a message and is regarded as an honour, not a symptom of a mental disorder. Further differences between the ICD and DSM are that the ICD claims that symptoms should be present for 1 month whereas the DSM claims symptoms should be present for 6 months. This poses a threat to the reliability and validity of diagnosis as a patient may be diagnosed differently depending on which of the tools are used. Furthermore, the DSM could be considered to be unethical as patients have to suffer with their symptoms for 6 months before they can be diagnosed and receive treatment. They may be a harm to themselves and to others during this time. An additional difference between the ICD and the DSM are that the ICD has two extra sub-types on top of the five they share with the DSM. The reliability here is questioned as a sufferer could be diagnosed as one type of schizophrenic according to the DSM and a different type according to the ICD. Reliability is measured using inter-rater reliability. This is the extent to which psychiatrists agree with each other on diagnosis. Studies have been done to assess the inter-rater reliability when diagnosing schizophrenia. Beck et al (1961) looked at the inter-rater reliability between 2 psychiatrists when considering the cases of 154 patients and found that the reliability was only 54%. However, Söderberg (2005) reported a concordance rate of 81% using the DSM-IV. This shows that whilst there is some discrepancy in diagnosis, the tools have improved over time which have in turn improved the reliability. Co-morbidity is another issue which poses a threat to reliability of diagnosis. Co-morbidity is when a patient is suffering from two or more mental disorders at one time. Many Schizophrenics also suffer from other disorders such as depression and bi-polar disorder. Comorbidity occurs in part because the symptoms of different mental disorders often overlap with each other. For example low motivation is a symptom of depression as well as a negative symptom of schizophrenia. How can diagnosis be consistent when one patient could be diagnosed with depression, and the other schizophrenia? In terms of validity, there is an issue with the classification of Schizophrenia. The subtype “Undifferentiated Schizophrenia” is essentially a 'rag bag' for sufferers whose symptoms are hard to classify. Patients can have a wide range of symptoms and therefore two patients classified as undifferentiated schizophrenics may not have any symptoms in common. A key study which highlights just how invalid or inaccurate diagnosis can be is by Rosenhan (1973). In his experiment, 8 psychologically healthy actors went into hospitals and pretended to be hearing voices saying “thud”, “hollow” and “empty”. They were admitted into the psychiatric hospitals and despite behaving normally once admitted, all but one were diagnosed as having schizophrenia and stayed at the institution between 7 and 52 days. This shows that diagnosis is not accurate or valid, as they diagnosed healthy people as being schizophrenic – they cannot distinguish between the sane and insane. In Rosenhan’s second experiment, he threatened more hospitals that he would be sending actors to pose as patients. 41 patients were suspected of being fake when Rosenhan actually hadn’t sent anyone at all! This demonstrates further that being accurate in diagnosis is extremely difficult. Although an influential study, Rosenhan’s experiment was carried out over 40 years ago therefore diagnostic tools have been updated since then and are hopefully more accurate. In addition, it highlights a further issue in relation to “labelling”. This is the idea that once someone is diagnosed, they have the “label” of schizophrenia with them, potentially, for the rest of their lives. Even though the actors in Rosenhan’s first experiment were behaving normally, because they had been labelled with schizophrenia, their behaviour was interpreted as so. For example, when they were observing behaviour of staff and writing notes, this was interpreted as “obsessive writing behaviour”. Labelling may lead to unemployment, poverty and even the self-fulfilling prophecy. Overall, there are many issues when diagnosing schizophrenia, particularly related to reliability and validity. Most diagnosis relies on self-report from patients which can have problems in terms of dishonesty and clarity. The psychiatrists completing the diagnosis may also be biased, whether that be intentionally or unintentionally. However, efforts have been made to improve the diagnostic tools over time, and practices such as inter-rater reliability, test re-test and blind diagnosis have helped to improve these further. Discuss biological explanations for schizophrenia (8+16 marks) Biological explanations of schizophrenia assume that the disorder is caused by abnormalities in the body – physiological abnormalities. Two of the main biological explanations are the genetic explanation and the dopamine hypothesis. Schizophrenia tends to run in families which could mean that it is a genetic disorder. This means that schizophrenia is transferred by hereditary means – it’s passed down or inherited through generations. Genetic explanations can be investigated using twin studies. Monozygotic (MZ) twins are identical (coming from the same egg), thus have identical genetic make-ups. Dizygotic (DZ) twins are non-identical, who share around 50% of their genetic make-ups, similar to ordinary brothers and sisters. MZ and DZ twins can therefore be directly compared as both sets are brought up together and thus share the same environment. Consequently, if MZ twins are more alike than DZ twins in, for example, having schizophrenia, then we can be fairly sure that it is due to genetic factors rather than the environment. We measure similarities in twins through concordance rates. This means the presence of the same trait in both members of a pair of twins, or the probability that one twin will have a certain characteristic if the other twin does. Research evidence for the genetic explanation comes from Gottesman (1991) who found a concordance rate of 48% for MZ twins and only 17% for DZ twins. Furthermore, Cardno (2002) found a concordance rate of 27% for MZ twins and 0% for DZ twins. Both of these studies therefore suggest a strong genetic component to schizophrenia. However, as the concordance rate is not 100% for MZ twins, then the cause of schizophrenia cannot be solely genetic; there must be other factors involved. A further issue with twin studies is that it is fairly rare to find twins, let alone twins who have schizophrenia, therefore the sample sizes are often very small in any research, making generalizability more difficult. In addition, it may be that MZ twins are treated more similarly than DZ twins so it could be the more similar environment and upbringing which is causing schizophrenia rather than a genetic component. Adoption studies are used to try and separate genetic factors from the environment. For example, if an adopted child has schizophrenia, but their adopted parents do not, we then look to their biological parents. If one of these parents does have schizophrenia then we can assume that it has been inherited by the adopted child, therefore it is caused by genetics not the environment. Kety (1994) found high rates of schizophrenia in individuals whose biological parents had the disorder but who had been adopted by psychologically healthy parents. Tienari (1991) conducted a Finnish Adoption Study and compared 155 adopted children whose biological mothers had been diagnosed with schizophrenia with a group of adopted children who had no family history of schizophrenia. 10% of the adopted group whose mothers had schizophrenia developed the disorder compared to only 1% in the matched group. These studies thus further demonstrate that schizophrenia has a reasonably strong genetic component. Although there is research support, this research must be considered carefully as much of the studies use small sample sizes and retrospective data which can affect its validity. In addition, diagnosis may be biased as psychiatrists may be more inclined to diagnose someone as schizophrenic when it runs in the family. It seems that genetics play a part in an individual’s predisposition to schizophrenia, rather than being the sole cause. This means that some individuals are at a greater risk for developing the disorder due to their genes, but that another factor interacts with this to cause the actual onset of schizophrenia. This is linked to the diathesis-stress model which is likely to be a better explanation for schizophrenia in which nature (genetics) combines with nurture (environment) to cause schizophrenia to develop. Due to this, the genetic explanation of schizophrenic can be seen to be reductionist as it is reducing a complex disorder to hereditary means without considering what triggers the onset of the disorder, such as sociocultural factors or cognitive difficulties. The genetic explanation is also deterministic as it suggests that those with a genetic vulnerability have an increased risk of schizophrenia, which ignores their free will to create a psychologically healthy environment for themselves. It may also cause individuals to feel helpless in terms of not being able to do anything to avoid a disorder that runs in their family. (THIS IS OBVIOUSLY TOO LONG IF YOU ARE TALKING ABOUT TWO BIOLOGICAL EXPLANATIONS BUT WANTED TO PUT THE WHOLE ESSAY FOR BOTH GENETICS AND DOPAMINE IN) An additional biological explanation of schizophrenia is the dopamine hypothesis. Dopamine is a neurotransmitter, which are chemicals that communicate signals in the brain. The dopamine hypothesis states that the brain of schizophrenic patients produces more dopamine than normal brains. From further research, it is now believed that schizophrenics have an abnormally high number of D2 receptors. The dopamine hypothesis was first put forward when it was discovered that people who took large quantities of amphetamines (a drug which increases dopamine) developed psychotic symptoms. Since then, much research has been done to support the role of dopamine in schizophrenia. Randrup et al (1966) gave rats amphetamines and found that they developed schizophrenia type symptoms. Whilst the generalizability can be questioned due to the use of rats, the findings have been replicated in humans also. In addition, evidence comes from post-mortems; Seidman (1990) completed postmortem examinations comparing the brains of schizophrenics with healthy patients. He found that people with schizophrenia have a larger than usual number of dopamine receptors, as well as an increase of dopamine in brain structures (left amygdala and caudate nucleus putamen). Finally, additional evidence can come from PET scans. These are scans which show the functioning of the brain. A drug that combines with dopamine receptors is injected in patients which then travels to the brain and binds to these receptors. A PET scan is then taken and the drug shows up as brightly lit areas. Kessler et al (2003) compared the brains of schizophrenics and non-schizophrenics through use of PET scans and found that the former had elevated levels of dopamine receptors. There is seemingly much support for the dopamine hypothesis coming from a variety of reliable scientific methods, therefore it is clear that dopamine does play a role in schizophrenia. However, the main problem with this explanation is related to causality. We don’t know whether excess dopamine causes schizophrenia or if it as a result of schizophrenia. This is something which is difficult, near impossible, to test as we’d need to study the brains of people before they develop schizophrenia to see if they had excess dopamine to begin with. As with all biological explanations, the dopamine hypothesis is reductionist as it is again reducing a complex disorder to chemicals in the brain, ignoring the individual’s environment and experiences which may have caused schizophrenia to occur. In addition, the explanation is deterministic, claiming that excess dopamine is increasing the risk of schizophrenia, thus ignoring the role of free will in the individual who may actually create a psychologically healthy environment for themselves. Nonetheless, the dopamine hypothesis has been extremely influential, particularly in the development of anti-psychotic drugs, which mainly work through blocking the dopamine receptors in the brain. On the whole, these drugs are effective in treating schizophrenics, however they don’t work for everyone and generally only target the positive symptoms, having little effect on negative symptoms. This suggests that the dopamine hypothesis may be an adequate explanation for the positive symptoms of schizophrenia such as hallucinations and delusions, but that further explanations are required for other aspects of this complex disorder. Discuss biological therapies for schizophrenia (8 + 16 marks) Anti-psychotic drugs are the most common biological treatment for schizophrenia. They are split into two types; typical (first generation) drugs, and atypical (second generation) drugs. Typical antipsychotics are based on the dopamine hypothesis as a cause of schizophrenia – that schizophrenics have elevated levels of dopamine in their brains. We cannot physically decrease the amount of dopamine or reduce the number of receptors so the next best thing is to block the receptors, and this is what typical antipsychotics do. Much research has been carried out to test the effectiveness of these first generation antipsychotics. Sampath et al (1992) studied their effectiveness by looking at patients who had been taking the antipsychotics for 5 years. One groups switched to a placebo drug whilst the other group continued to take the typical drug treatment. The researchers found that 75% of the patients taking the placebo drugs relapsed within 1 year; compared with only 33% of patients who continued taking the real drug. Whilst this study can be questioned in terms of its ethics, it clearly shows that typical drugs can be effective in lowering relapse rates. Effectiveness can also be assessed in relation to symptom reduction; Davis et al (1989) conducted a meta-analysis of over 100 studies investigating the effectiveness of typical antipsychotics and found that 70% had improved conditions and reduced symptoms after 6 weeks. Whilst these are both optimistic findings, the main problem in typical antipsychotics is that they only appear to reduce positive symptoms, such as hallucinations and delusions, but have little effect on negative symptoms such as lack of motivation. In addition, they also cause severe side-effects for the majority of patients ranging from drowsiness and weight changes, to tardive dyskinesia, a disorder resulting in involuntary repetitive movements. To overcome the lack of effect on negative symptoms, atypical antipsychotics have since been developed. In addition to blocking the dopamine receptors in the brain, atypical drugs also block the serotonin receptors, and these seem to make the drug more effect in treating the negative symptoms of schizophrenia as well. Schooler et al (2005) compared the effectiveness of typical and atypical anti-psychotic drugs. They found that 75% of patients experienced at least 20% reduction in their symptoms when taking atypical drugs. 55% of patients on typical relapsed compared to 42% on atypical. Side effects were also fewer with atypical. Research seems to support that atypical drugs are more effective in reducing a range of symptoms, and that they produce fewer side effects than the typical antipsychotics. However, recent research seems to suggest that atypical antipsychotics can also produce severe side effects, most notably, a disorder called Agranulocytosis which effects the immune system by lowering the amount of white blood cells. This can be fatal, therefore patients need to have check-ups regularly. Antipsychotics are the most common form of treatment for schizophrenia and have many advantages in that they can be administered relatively quickly and cheaply, therefore can reduce symptoms quickly and prevent patients from being a danger to themselves or others. However, as we have seen there are also disadvantages to this form of treatment, particularly in terms of the side-effects caused. In addition, they only offer a shorter-term solution, as usually once patients stop taking the drugs, the symptoms return. Because of this, what is known as a “revolving door” policy occurs in which patients are constantly in and out of hospitals as their symptoms are reduced and then return again. Drugs are also only really focusing on symptoms of schizophrenia rather than more the underlying causes, ignoring self-help strategies for the patient to cope better with the disorder by themselves. This makes the treatment reductionist, but does mean it can be combined with therapies such as CBT to make a more holistic long-term successful treatment for individuals. ECT is an alternative form of biological treatment used as a last resort if drug treatment or therapy is not working. It is very rarely used in this country to treat schizophrenia and is based on little evidence; little is known about how/why it works. During treatment the patient is first put under anaesthetic and electrodes are attached to their temples. An electric current of approximately 70-130v is then passed through the brain for about 0.5 seconds. The current causes the patient to have a seizure which they do not remember afterwards. ECT is usually given 3 times a week for approximately 5 weeks. Research has been conducted to see whether ECT is an effective treatment for schizophrenic patients. Tharyan (2006) reviewed studies of ECT treatments, concluding that there was some evidence for the shortterm relief of schizophrenic symptoms, but that the treatment was best used in conjunction with drugs. Chanpattana (2007) conducted a study in which patients with schizophrenia, who had previously proved resistant to treatment, received ECT on its own or in combination with antipsychotic drugs. He found that ECT produced a marked reduction in positive symptoms, especially when used in combination with drug therapy. ECT plus drug therapy also led to significant improvements in quality of life and social functioning. These studies therefore show that ECT may be effective at reducing symptoms, but probably only when combined with other treatment methods. The problem with ECT as a treatment is that it is rarely used therefore any studies which seem to support its use are made up of very small sample sizes which then limit the generalizability to others. In addition, any evidence for ECT only demonstrates that it has a short-term effect therefore it is not a long-term solution to schizophrenia and is really only reducing symptoms rather than providing a cure for the disorder. There are also side-effects to this treatment such as memory loss and jaw injuries. ECT tends to be unilateral when administered now (one side of the brain), however, and this seems to reduce the side effects previously produced. Overall, ECT lacks conclusive evidence on its effectiveness and little is known about why inducing a seizure reduces psychotic symptoms. The ethics of this treatment have been questioned extensively, as ECT was previously used to experiment on patients and to control unruly behaviour in psychiatric hospitals. It may well be effective in treating those who are resistant to other forms of treatment but should be administered with caution. Discuss psychological explanations for schizophrenia (8+16 marks) One psychological explanation is the cognitive approach. It assumes that schizophrenia, like all mental disorders, is caused by faulty thinking, however it also assumes that these cognitive deficits are due to underlying neurophysiological abnormalities, therefore incorporating the biological explanation as well. We are normally able to filter incoming stimuli and process them to extract meaning; it is thought that these filtering mechanisms and processing systems are defective in the brains of schizophrenics. Frith (1992) argues that we usually filter information at a preconscious level and that only what is relevant reaches the conscious level where it is processed. In schizophrenics, positive symptoms arise as this filter is “faulty” and all information reaches the conscious level so irrelevant information is seen as relevant. More specifically, individuals with schizophrenia may have problems with self-monitoring, and so fail to keep track of their own intentions. As a result, they mistakenly regard their own thoughts as having come from someone else (thus explaining auditory hallucinations). Similarly, they may attribute some of their thoughts or movements to others, explaining symptoms such as delusions of control. He believes this ‘faulty filter’ is caused by abnormalities in the pathway connecting the hippocampus to the prefrontal cortex. Furthermore, Helmsley (1993) suggests there is a substantial breakdown in the relationship between memory and perception in schizophrenics. In non-schizophrenics, individuals give meaning to new sensory input by using subconsciously previously stored knowledge (schemas). However, people with schizophrenia are often unable to activate schemas which would allow them to predict what will happen next, therefore their concentration is poor, and they attend to unimportant or irrelevant aspects of the environment. Their poor integration of memory and perception leads to disorganised thinking and behaviour. Helmsley believes these deficits can be attributed to abnormalities in the hippocampus. There is much evidence to support the role of cognitive deficits in schizophrenia, as well as the biological irregularities which may underlie these cognitive issues. McGuigan (1966) found that the larynx (voice box) of patients with schizophrenia was often active during the time they claimed to be experiencing auditory hallucinations. This suggests that they mistook their own inner speech for that of someone else. Liddle and Morris (1991) found out that people with schizophrenia perform poorly on the Stroop test, where participants are required to suppress the desire to read out the colour a word is written and just read out the word. This demonstrates that schizophrenic patients have difficulty in deciding which information to attend to and what is relevant/irrelevant. Moreover, PET scans show under-activity in the frontal lobe of the brain of schizophrenics, which is linked to self-monitoring, and so provides biological support for this explanation. The cognitive explanation is clearly plausible and has much research to support a lack of effective cognitive processing in schizophrenic patients. This has led to a successful treatment for schizophrenia is cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) where cognitive deficits are addressed. It is also less reductionist than other explanations, as it accepts that biological mechanisms are likely to underlie cognitive deficits so incorporates another explanation for the disorder. However, there are problems with this explanation in that it can’t really account for negative symptoms, mainly focusing on the positive symptoms of schizophrenia. There are also problems with causality; it is not clear whether the cognitive dysfunction is a cause or effect of the disorder. Prospective and longitudinal research with children at risk for schizophrenia being assessed over time or with self-monitoring is necessary to establish the direction of the effect. Lastly, the cognitive explanation does not explain why the delusions and hallucinations that patients experience are often abusive, mostly critical, and command them to commit reprehensible acts. We all have internal speech but although it might be critical at times it does not usually pretend to be God or command us to rape or kill. An alternative psychological explanation is that which focuses on family issues as a cause of schizophrenia. This explanation is strongly linked with psychodynamic assumptions regarding the importance of childhood experiences as a cause for mental disorders. The first idea is that of a “schizophrenogenic mother”. A schizophrenogenic has actions that are often contradictory – verbally accepting yet behaviourally rejecting. This can set up faulty communication between both mother and child and can lead to the onset of schizophrenia. Linked to this is the “double bind hypothesis”. A child has repeated experiences with one or more family members in which he/she receives contradictory messages (double bind communication). For example, telling the child ‘I love you’ whilst rejecting physical affection. Repeated exposure to such messages causes the child to resort to self-deception and to develop a false concept of reality to communicate effectively. It is suggested that this could lead to some of the symptoms of schizophrenia, such as hallucinations, delusions and disorganised thoughts and behaviour. Evidence for the double bind hypothesis comes from Bateson (1956) who reports clinical evidence based on interviews and observations. Bateson found the use of double bind communication by parents of schizophrenia patients. There are, however, issues with this research as there may be an element of “confirmatory” researcher bias as they are interpreting behaviour to fit in with their own theory. In addition, as Bateson was observing the family interaction of patients that had already been diagnosed with schizophrenia, we do not know if the double bind communication was as a result or a cause of the diagnosis. Berger (1965) used a retrospective method. He gave out a questionnaire containing 30 double bind statements and asked the participants to rate them on a 4 point scale in terms of how frequently they recalled their mothers using these type of statements. Berger found that the schizophrenics consistently reported a higher incidence of these statements than one of the comparison groups (college students). However he found that the schizophrenics’ scores were not significantly higher than the other comparison groups who also had psychiatric and medical conditions, therefore double bind communication may be linked to mental disorders in general rather than specifically to schizophrenia. The next idea related to family issues, more as a factor in relapse rather than as a cause of schizophrenia, is that of “Expressed Emotion” (EE). EE is characterised by hostility, criticism and over involvement in the family environment after someone has been diagnosed. Brown et al (1966) examined progression of schizophrenia when patients were discharged from hospital and lived with their families. Families were either rated as high EE or low EE in terms of the frequency of statements that were critical, resentful or overprotective. 58% of patients who returned to high EE families relapsed, compared to only 10% of those who returned to low EE families. Again, there are problems in the methodology of this study in terms of the subjective measure for categorising high or low EE families as well as issues such as researcher bias and demand characteristics. The family issues explanation is further supported by family intervention as a successful treatment of schizophrenia. By focusing on family communication and interaction, the treatment can be effective in preventing relapse in a lot of patients. However, difficulty stems in judging causality as it is unclear whether factors such as double-bind communication and expressed emotion are present before or after the diagnosis. Research that uses retrospective data is also likely to be less valid. Furthermore, many argue that the explanation puts blame on the families/parents which may be unfair so could be seen to be unethical. Many people may experience contradictory behaviour or communication by family members but not all of these people develop schizophrenia. There is likely to be other factors involved, such as biological abnormalities, and family issues may act as a trigger to a biological predisposition of the disorder. Discuss psychological therapies for schizophrenia (8+16 marks) A common form of psychological therapy used when treating schizophrenia is cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT). This treatment is based on the cognitive explanation for schizophrenia: that it stems from faulty mental processes. Behavioural aspects are also added so that clients can be provided with self-help strategies that should make the treatment more successful in the long-term. For CBT to be effective, first therapist and client must build a trusting relationship. This is the main difficulty of CBT as a treatment of schizophrenia, as not all patients will be willing to trust others, or be rational enough to communicate effectively. During sessions, patients discuss their confusing and distressing experiences and together with the therapist will try and uncover any patterns or triggers in these experiences. Hallucinations and delusions are gently challenged, and more plausible explanations can then be suggested, which can then be reality tested. Strategies are then discussed in how better to deal with distressing experiences. Evidence for the effectiveness of CBT comes from Chadwick et al (1996) who explains a case study of a patient who believed he could make things happen by just thinking them. His beliefs were gently challenged (cognitive aspect) and a reality test experiment was set up (behavioural aspect) in which the patient was shown paused videos and asked to predict what would happen next. The patient failed to make any correct predictions in 50 trials therefore could then understand that he didn’t have power to control events with his thoughts. This in turn reduced his delusional thinking. A more specific form of CBT is known as Coping Strategy Enhancement (CSE). This form of CBT is aimed at teaching individuals to develop and apply different strategies that will reduce the frequency and intensity of symptoms such as hallucinations and delusions. Cognitive strategies include use of distraction, concentration and positive self-talk. Behavioural strategies may include initiation of social contact, relaxation techniques, and shouting to block out auditory hallucinations. A specific strategy is practiced within a session and the client is helped through any problems applying it. Homework tasks are then set to keep practising outside of therapy and to keep a record of how it’s worked. Tarrier (1993) found a significant reduction in positive symptoms in a CSE group as opposed to nontreatment group. There was also a significant improvement in effective use of coping skills. 73% of the CSE sample reported that that strategies were successful in managing symptoms. CBT appears to be an effective treatment with schizophrenic patients and there is much research to support this. The main positive is that patients are provided with strategies which they can use independently outside of therapy giving them empowerment and making the treatment more successful in the long-term. It is targeting both the symptoms and causes of schizophrenia and doesn’t provide unpleasant side effects as in other treatments of the disorder, such as antipsychotic drugs. Nonetheless, there are problems targeting all symptoms, although in theory, strategies can be adapted for dealing with negative symptoms as well as positive symptoms. It is therefore not suitable for all patients, in particular, as stated earlier, with those who have severe symptoms that make it difficult to build a relationship with the therapist. Furthermore, CBT when compared to drug treatment, is very expensive and time consuming and will take longer to reduce dangerous symptoms, again, in comparison to drugs. Although aiming to make patients more self-sufficient in dealing with schizophrenia, some patients can actually become dependent on their therapist and this makes improvements after therapy sessions have stopped a difficulty. Overall, CBT is an extensive treatment and can be used in conjunction with antipsychotic drugs to provide a more successful long term solution to schizophrenia. An additional psychological therapy for schizophrenia is that of Family Therapy which use family intervention strategies. The main focus of family intervention strategies is inclusion and the sharing of information. Sessions aim to develop a cooperative and trusting family group. The therapist provides information on the cause, course and symptoms of schizophrenia, while family members, including the sufferer, bring to the group their own experience of dealing with the disorder. The whole family are then provided with coping strategies that enable them to manage the day to day difficulties of having someone with schizophrenia in the family. They also learn more constructive ways of interaction and communication and are encouraged to focus on good things that happen rather than bad things. In addition, the family are trained to recognise the early signs of relapse in the schizophrenic patient so that they can respond quickly and hopefully prevent this from occurring. There is research support to suggest that family communication and interaction can have a huge effect on whether schizophrenic patients relapse, for example, Brown et al (1966) found that 58% of patients who returned to high EE families (critical and hostile) relapsed, compared to only 10% of those who returned to low EE families. This therefore suggests that family intervention strategies will help reduce relapse rates after diagnosis. This is demonstrated through research by Pharoah (2003) who did a meta-analysis of studies which investigated this treatment method. He found that family interventions were effective in reducing relapse rates and admission to hospital. Pharoah also found improved compliance with taking medication in patients who had received family therapy. A difficulty with the research is how relapse rates are defined. Is it based on when they are re-hospitalised? Or when they experience severe symptoms again? Different studies may use different definitions and we may be unable to know if a patient is re-experiencing symptoms again unless they come forward, therefore some relapses may go unnoticed. Family therapy is based on the valid assumption that a more supportive network for the patient after diagnosis of schizophrenia will help them to improve, and make it less likely that they will need to be rehospitalised. However, its effectiveness is very dependent on whether the patient lives with or near their family and the type of family that they have. The patient’s family must be willing and committed to take part in the therapy and consequently this treatment will not be suitable for all patients. It could also be questioned whether the therapy is more focused on equipping the family to deal with a schizophrenic member rather than helping the patient overcome the disorder. It may be that family therapy should be looked at more as a way of helping people cope with schizophrenia rather than a cure for the actual disorder itself. It is likely that another treatment, such as antipsychotic drugs, would need to be used in concordance with family therapy to see real improvement.