Cost Effective Evaluation of the Arise Project

advertisement

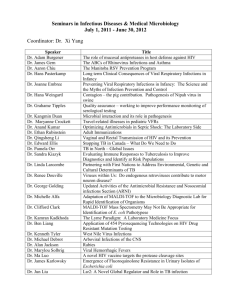

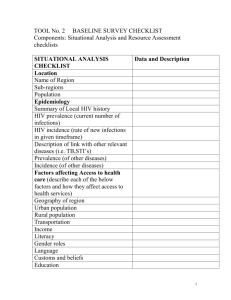

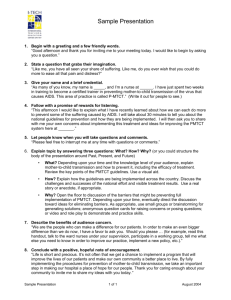

COST EFFECTIVENESS ANALYSIS & INFECTIONS AVERTED OF PMTCT SERVICES BY COMMUNITY AND FACILITY STRENGTHENING IN MASHONALAND CENTRAL PROVINCE, ZIMBABWE Ravikanthi Rapiti¹, Angela Mushavi2 , Ann Levine3, Julie Pulerwitz1 & Ibou Thior 3 1Population Council, 2Zimbabwe Ministry of Health, 3 PATH International AIDS Economic Network 19 July 2014 Melbourne, Australia PMTCT in Zimbabwe • In 2009 – Pregnant women attended ANC—54%1 – ANC HIV prevalence—16% (20% in Mashonaland Central) – MTCT rate—30%2 • Roll out of 2010 WHO Option A guidelines in 2011 • Health facilities required significant training and mentoring to provide these newer, more complicated regimens • To increase uptake, communities, families and males also needed to be engaged 1World Health Organization. Antiretroviral drugs for treating pregnant women and preventing HIV infection in infants: towards universal access. Available at: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/mtct/antiretroviral2010/en/index.html Accessed 29 April 2013. 2UNAIDS Global AIDS Response Progress Report, 2012: Zimbabwe Country Report. Available at: http://www.unaids.org/en/dataanalysis/knowyourresponse/countryprogressreports/2012countries/ce_ZW_Narrative_Repo rt.pdf. Accessed 29 April 2013. Objectives • Evaluation of the Arise PMTCT project implemented in 21 sites in Mashonaland Province, Zimbabwe that sought to address whether a strengthened PMTCT package could improve: – PMTCT coverage – Outcomes – Cost and cost effectiveness • Could a paediatric infection be averted in <500USD per infection? Arise study sites Project timeline (45 months) Project start up Sept 2010 ARISE intervention concludes Baseline survey Aug-Sept 2011 Sept Aug-Sept 2010 2011 March 2014 2012 2013 April 2014 May 2014 ARISE intervention initiated End line survey Project closure Dec 2011 April 2014 May 2014 Components of intervention • Facility level – – – – Provision of point-of-care CD4 machines Training & mentoring of providers Strengthening completion of routine PMTCT registers Strengthening links with central laboratory • Community level – Awareness campaigns, dramas – Follow up with clients who missed scheduled visits in the PMTCT cascade – Sensitizing community leader & faith healers – Establishing support groups – Outreach and targeting of men – Strengthening community and health facility linkages Data sources for the evaluation • Financial reports on expenditures for costing • An activity-based costing approach • Costing templates were developed • Types of costs were defined • Infections averted were calculated • Sensitivity analysis was conducted • Costing was determined How many HIV infections were averted over the intervention period? Estimating infant HIV infections averted • Modeled estimates of infant HIV infections. – Estimated number of HIV-exposed infants were derived from the HIV prevalence rate times the estimated number of live births per year in the project catchment area. – Validated data from routinely completed PMTCT facility registers Estimated number of infections averted Lower Limit Upper Limit 15,968 20,508 HIV prevalence in pregnant women (as proportion) 16% 20% Total number of HIV+ pregnant women delivering per year 2,554.9 4,101.6 # deliveries per year Year 1 Year 2 Year 3 Year 4 (Quarter 1) Total Lower Limit 361 626 649 187 1,822 Upper Limit 580 1,005 1,041 300 2,925 What were the costs per infection averted? Describing costs Type of cost Cost category/cost items Start up Financial (programmatic costs defined as DFATD funded financial expenditure used to deliver the services to beneficiaries) Micro-planning, developing materials, training & mentoring, sensitization Economic (financial costs plus the value of shared project costs and the value of all donated goods and services) Start-up financial costs value of all donated goods and services, and of resources already financed to provide comprehensive care and treatment Recurrent Health commodities & storage/transport, personnel, capital (annualized), transport & travel, office facilities, admin, & meetings Data sources Indirect programmatic costs Cell phone & communication costs for nondirect staff, rent & office bills, office repairs & upkeep Project expense reports (ZAPP, CHAI & PC); Facility data; Ministry of Finance; Recurrent economic Financial indirect MoH costs and other shared programmatic costs including HCW costs plus that costs and the were shared with laboratory and ARV other programs, health commodity costs including rent for the CHAI office Costing Period (2011–2013) Cost category DFATD upfront financial Start-up 233,555 Recurrent 363, 986 Indirect programmatic costs 58,014 Total costs (no indirect programmatic costs) 867,120 Total costs (with indirect programmatic costs) 655,555 Costing Period (2013-2014) Cost category DFATD upfront financial Start-up 34,500 Recurrent 235,079 Capital costs 21,443 Indirect programmatic costs 58,014 Total costs (no indirect programmatic costs) 291,022 Total costs (with indirect programmatic costs) 349,036 Final Costing • The front line costs for 2011–2013 included both the facility and the community intervention. • The community intervention continued until the end of the project (February 2014). • The cost of infections averted during 2013– 2014 is a range between $ 537.81 and $ 335.30 when the prevalence is varied between 16 percent and 20 percent respectively. Conclusions • This project demonstrated that a combined community and health facility approach has the potential to improve access and retention across the PMTCT cascade. • Community strategies on retention and male involvement as well as cost data will be important contributions as Zimbabwe now moves to Option B+. Conclusions (con’t) • Use of routine real world programmatic data for estimating infections averted is a strength of this study. • Even though a more efficacious PMTCT program, Option A, costs more than previous regimens, the cost of averting infections are lower compared to lifetime treatment costs. Considerations • Lack of control facilities. • Contributions of other stakeholders and other donors to national and provincial level efforts. • Investments in infrastructure and human capacity development will remain. Acknowledgements This presentation was produced under Arise—Enhancing HIV Prevention Programs for At-Risk Populations, through financial support provided by the Canadian Government through Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada, and via financial and technical support provided by PATH. Arise implements innovative HIV prevention initiatives for vulnerable communities, with a focus on determining cost-effectiveness through rigorous evaluations.