The Project Development Objective is to support the strengthening

advertisement

Document of

The World Bank

FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY

Report No: 69657-TO

PROJECT PAPER

FOR

SMALL RECIPIENT EXECUTED TRUST FUND GRANT

US$2.90 MILLION EQUIVALENT

TO THE

KINGDOM OF TONGA

FOR AN ENERGY ROADMAP INSTITUTIONAL AND REGULATORY FRAMEWORK

STRENGTHENING PROJECT

June 8, 2012

This document is being made publicly available prior to approval. This does not imply a

presumed outcome. This document may be updated following management consideration and

the updated document will be made publicly available in accordance with the Bank’s policy

on Access to Information.

i

CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS

(Exchange Rate Effective May 2012)

Currency Unit = TOP

TOP 1.80 = US$1

US$ = SDR 1

FISCAL YEAR

January 1 – December 31

ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS

ADB

ADO

ASTAE

BMZ

BP

CA

CBD

CCCPIR

CEO

CO2

CPI

CQS

CS

CSO

DA

DP

DPO

ECC

EIA

EIRR

EMP

ESMF

FAESP

FM

FY

GDP

GHG

GIZ

GoNZ

GOT

GWH

HV

IBRD

Asian Development Bank

Automotive Diesel Oil

Asia Sustainable and Alternative Energy Program

Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development

Bank Guidelines

Connection Agreements

Central Business District

Coping with Climate Change in the Pacific Island Region

Chief Executive Officer

Carbon Dioxide

Consumer Price Index

Consultant Quality Selection

Competitve Selection

Community Service Obligations

Designated Account

Development Partners

Development Policy Operation

Electricity Concession Contract

Environmental Impact Assessment

Economic Internal Rate of Return

Environmental Management Plan

Environmental and Safeguard Management Framework

Framework for Action on Energy Security

Financial Management

Financial Year

Gross Domestic Product

Green House Gas

Die Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit

Government of New Zealand

Government of Tonga

Gigawatt Hour

High Voltage

International Bank of Reconstruction and Development

ii

ICB

IDA

IFR

IPESP

IU

IUCN

JICA

kVA

kWh

LARAP

LCS

LCT

LED

LPG

LV

MoF

MPE

MR

MW

NCS

NOx

NPV

O&M

OP

OPR

PDO

PEC

PIAC

PIC

PPA

PRIF

PV

QCBS

RAV

RE

REEEP

RETF

SAIDI

SCADA

SI

SOE

SPC

SV

TA

TERM

TERM-A

Internation Competitive Bidding

International Development Association

Interim Unaudited Financial Report

Implementation Plan on Energy Security

Implementation Unit

International Unit for the Conservation of Nature

Japan International Cooperation Agency

Kilo Volt Ampere

Kilo Watt Hour

Land Acquisition and Resettlement Action Plans

Least Cost Selection

Local Coast Tankers

Light-Emitting Diode

Liquefied Petroleum Gas

Low voltage

Ministry of Finance

Ministry of Public Enterprise

Medium Range

Megawatt

Non-competitive Selection

Nitrogen Oxides

Net Present Value

Operation and Maitenance

Operational Guidelines

Operational Procurement Review

Project Development Objective

Pacific Environment Community

Pacific Infrastructure Advisory Center

Pacific Island Countries

Power Purchase Agreements

Pacific Region Infrastructure Facility

Photovoltaic

Quality- and Cost-Based Selection

Regulated Asset Value

Renewable Energy

Regional Energy and Energy Efficiency Partnership

Recipient Executed Trust Fund

System Average Interruption Duration Index

Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition

Sensitivity Indicator

State Owned Enterprise

Secretariat of the Pacific Community

Switching Value

Technical Assistance

Tonga Energy Road Map

Tonga Energy Road Map Agency

iii

TERM-C

TERM-IU

TGIF

TOP

TPL

US$

WA

WB

Tonga Energy Road Map Committee

Tonga Energy Road Map Implementation Unit

Tonga Green Investment Fund

Tongan Pa'anga

Tonga Power Limited

United States Dollars

Withdrawal Application

World Bank

Regional Vice President:

Country Director:

Sector Director:

Sector Manager:

Task Team Leader:

Pamela Cox

Ferid Belhaj

John Roome

Charles Feinstein

Roberto G. Aiello

iv

KINGDOM OF TONGA

Tonga Energy Roadmap Institutional and Regulatory Framework Strengthening

Project

TABLE OF CONTENTS

1. STRATEGIC CONTEXT

a. Country Context

b. Sectoral and institutional context

c. Higher Level Objectives to which the Project Contributes

1

1

3

14

II. PROJECT DEVELOPMENT OBJECTIVES

15

a.

b.

c.

PDO

Project Beneficiaries

PDO Level Results Indicators

15

15

15

III. PROJECT DESCRIPTION

a.

b.

c.

16

Project components

Project Financing

Lessons Learned and Reflected in the Project Design

IV. IMPLEMENTATION

a.

b.

c.

V.

17

Institutional and Implementation Arrangements

Results Monitoring and Evaluation

Sustainability

KEY RISKS AND MITIGATION MEASURES

VI. APPRAISAL SUMMARY

a.

b.

c.

d.

e.

f.

16

16

17

17

20

20

20

23

Economic and Fiscal Impacts

Poverty and Social Impacts

Financial Management

Procurement

Social (including Safeguards)

Environment (including Safeguards)

23

30

31

32

32

32

Annex 1: Results Framework and Monitoring

34

Annex 2: Detailed Project Description

37

Annex 3: Implementation Arrangements

41

Annex 4: Role of Partners

54

Annex 5: Map of the Kingdom of Tonga

59

v

KINGDOM OF TONGA

ENERGY ROADMAP INSTITUTIONAL AND REGULATORY FRAMEWORK

STRENGTHENING PROJECT

SMALL RECIPIENT EXECUTED TRUST FUND GRANT PROJECT PAPER

EAST ASIA AND THE PACIFIC

EASNS

Date: June 8, 2012

Country Director: Ferid Belhaj

Sector Director: John Roome

Sector Manager: Charles M. Feinstein

Team Leader:

Roberto G. Aiello

Project ID:

P131250

Instrument:

SIL

Sector(s): Energy

Theme(s): General energy sector (100%)

EA Category: C

Recipient: Kingdom of Tonga

Implementing Agency Component 1: Tonga Energy Roadmap Implementation Unit (TERM-IU)

Contact Person: ‘Akau’ola (TERM-IU Director)

Telephone No.: +676 24794

Fax No.: +676 22700

Email: akauola@gmail.com

Implementing Agency Component 2: Tonga Power Limited (TPL)

Contact Person: John von Brink (Chief Executive)

Telephone No.: +676 27390

Fax No.: +676 23047

Email: jvanbrink@tongapower.to

Start

Date:

Project Implementation

Period:

July 1, 2012

Expected Effectiveness Date:

July 1, 2012

Expected Closing Date:

December 31, 2015

End

Date:

June 30, 2015

.

Project Financing Data(US$M)

[ ] Loan

[X] Grant

[ ] Credit

[ ] Guarantee

[X] Other

For Loans/Credits/Others

Total Project Cost (US$M):

4.00

Total Bank Financing (US$M):

2.90

.

vi

Financing Source

Amount(US$M)

BORROWER/RECIPIENT

1.10

AusAID/PRIF Grant

2.50

ASTAE

0.40

Others

0.00

Total

4.00

.

Expected Disbursements (in US$ Million)

Fiscal Year

2013

2014

2015

Annual

0.70

1.20

1.00

Cumulative

0.70

1.90

2.90

.

Project Development Objective(s)

The Project Development Objective is to support the strengthening of the institutional and regulatory

framework of the Tonga Energy Roadmap.

.

Components

Component Name

Cost (US$

Millions)

Component 1: Strengthening the Energy Sector Framework and Structure

(Implementing Agency: TERM-IU). This component will support the Government of

Tonga to strengthen the functioning of the TERM-IU including through technical

assistance in the areas of: (i) energy sector policy; (ii) environmental and social

safeguard frameworks; (iii) petroleum price risk management strategy; (iv) feasibility

studies for power generation from renewable sources; (v) detailed surveys for electricity

use; and (vi) development of a communication plan (including awareness and

dissemination material in local language) for the Energy Roadmap in order to rally key

stakeholders around long-term goals and activities being implemented, thus mitigating

risks of misinformation.

2.10

Component 2: Preparing TPL for Renewable Energy Supply (Implementing Agency:

TPL). This component will support TPL to strengthen its capacity to: (i) carry out power

system modeling to determine the most cost effective way to diversify energy

generation, with a focus on achieving a high long-term renewable and distributed energy

penetration; (ii) design and specify upgrades to monitor, control, and protect systems to

ensure a reliable and secure supply of energy through the electricity system with high

levels of renewable energy generation; (iii) develop standards and procedures for

connection to the power system by independent power producers; and (iv) develop (in

conjunction with TERM-IU and to be approved by TERM-C) a power system plan for a

period of five years focusing on specific renewable energy technology projects such as

solar, wind, biomass and biofuels, but also covering energy storage options and demand

side management.

1.90

vii

.

Compliance

Policy

Does the project depart from the CAS in content or in other significant respects? Yes

[ ]

No

[x]

Does the project require any waivers of Bank policies?

Yes

[ ]

No

[x]

Have these been approved by Bank management?

Yes

[ ]

No

[x]

Is approval for any policy waiver sought from the Board?

Yes

[ ]

No

[x]

Does the project meet the Regional criteria for readiness for implementation?

Yes [ x ] No

[

.

Safeguard Policies Triggered by the Project

Yes

No

Environmental Assessment OP/BP 4.01

X

Natural Habitats OP/BP 4.04

X

Forests OP/BP 4.36

X

Pest Management OP 4.09

X

Physical Cultural Resources OP/BP 4.11

X

Indigenous Peoples OP/BP 4.10

X

Involuntary Resettlement OP/BP 4.12

X

Safety of Dams OP/BP 4.37

X

Projects on International Waterways OP/BP 7.50

X

Projects in Disputed Areas OP/BP 7.60

X

.

Legal Covenants

Name

Recurrent

Maintain TERM-A, TERM-C and TERM-IU

Due Date

Yes

Frequency

Always

Hire key staff for TERM-IU

3 months after

effectiveness

Adopt Operational Manual

1 month after

effectiveness

Maintain TPL implementing unit

Yes

Always

IFR reporting

Yes

Quarter

Progress reports

Yes

Semester

Signing of legal documents and legal opinions

At effectiveness

.

viii

]

Team Composition

Bank Staff

Name

Title

Unit

Roberto G. Aiello

Senior Energy Specialist, Task Team Lead

EASNS

Tendai Gregan

Energy Specialist, co-Task Team Lead

EASNS

Wendy Hughes

Lead Energy Economist

SEGES

Natsuko Toba

Senior Economist

EASIN

Ashok Sarkar

Senior Energy Specialist

SEGEN

Isabella Micali Drossos

Senior Councel

LEGES

Aleta Moriarty

Communications Officer

EACNF

Stephen Paul Hartung

Financial Management Specialist

EAPFM

Haiyan Wang

Finance Officer

CTRLN

Cristiano Costa e Silva Nunes

Senior Procurement Specialist

EAPPR

Nicole Forrester

Program Assistant

EACNF

Paul Fulton

Energy Consultant

EASNS

Martin Swales

Energy Consultant

EASNS

Penelope Ruth Ferguson

Environmental Consultant

EASIS

Ann McLean

Social Consultant

EASNS

Nicolas Drossos

Consultant

EASNS

Siosaia Tupou Faletau

ADB/ WB Liaison Officer

EACNF

Non Bank Staff

Name

Title

Office Phone

City

Locations

Country

First

Administrative

Division

Location

ix

Planned

Actual

Comments

I.

STRATEGIC CONTEXT

a. Country Context

1.

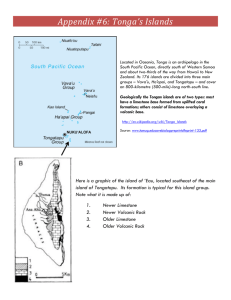

Tonga is a small, remote country that is highly vulnerable to external economic shocks

and natural disasters. Tonga’s population of 104,000 is dispersed across 36 of the 176 islands

that make up the archipelago. Located in the South Pacific, Tonga is one of the most remote

countries in the world, when measured by indicators of proximity to major markets. Small size

and remoteness combine to push up the cost of economic activity in Tonga, limiting the scope

for Tonga’s exports of goods and services to be competitive in world markets. These same

factors also push up the cost of providing public services in Tonga, due to Tonga’s limited

potential to exploit economies of scale in public and private sector activities. In addition, the

openness of Tonga’s economy and the lack of diversification of its sources of foreign exchange

make Tonga highly vulnerable to external economic shocks, while its geographical

characteristics make it highly vulnerable to natural disasters.

2.

Like other small, remote economies, Tonga depends on a very limited number of sources

for its foreign exchange earnings. About one-third of Tongans live abroad, primarily in the US,

New Zealand, and Australia and the remittances they send home are Tonga’s largest source of

foreign exchange. Over the last decade, remittances have averaged just fewer than 32 percent of

GDP. Tourism is Tonga’s next largest source of foreign exchange earnings, with tourism receipts

having averaged about 6 percent of GDP over the last decade. Over this period, tourism receipts

have been on an increasing trend. In contrast, Tonga’s merchandise export receipts which have

averaged about 5 percent of GDP over the last decade have been on a declining trend. Tonga also

receives significant development assistance, with cash grants averaging 3 percent of GDP over

the last decade but 5.1 percent of GDP over the last five years, reflecting an increasing trend.

Tonga also receives significant in-kind grants, which amounted to some 3 -6 percent of GDP in

each of the last two years1.

3.

Also like other small, remote economies, Tonga has a relatively undiversified economic

base. Agriculture, forestry and fishing contribute approximately 20 percent of Tonga’s GDP2,

and have been gradually declining over the course the last decade. Semi-subsistence agriculture

is, however, critical to the livelihoods of the majority of households in Tonga, particularly in

rural areas and the outer islands. Secondary industries, particularly construction activities, also

contribute approximately 20 percent of Tonga’s GDP. Service industries dominate the economy,

among which government services at about 15.5 percent of GDP are the largest component,

closely followed by commerce, restaurants and hotels at about 14.5 percent of GDP. This

category is dominated by wholesale and retail trading activities, which largely distribute

imported goods.

Energy in the Economy

4.

Energy is a fundamental building block for Tonga in its social and economic

development and in enhancing the livelihoods of all Tongans. It affects all businesses and every

1

2

Tonga, Ministry for Finance and National Planning.

Tonga, Ministry for Finance and National Planning.

1

household. Accessible, affordable and sustainable electricity that is environmentally responsible

and commercially viable is a high priority. Tonga is highly dependent on imported fuels to meet

its overall energy requirements. In 2000, when the last energy balance for Tonga was compiled,

imported petroleum products accounted for about 75% of Tonga's total energy needs. Currently,

all grid-supplied electricity, which accounts for over 98% of electricity used in Tonga, is

generated using imported diesel fuel. Over 95% of Tongans are connected to grid-based supply

of electricity.

5.

Tonga's total fuel imports account for about 25% of all imports and about 10% of GDP.

Hence changes in the price and amount of petroleum imports have a significant impact on

Tonga’s balance of payments situation and inflation. In particular, sudden price shocks can be

difficult to absorb. Automotive diesel oil, (ADO) (i.e. diesel) accounts for about two thirds of

petroleum imports; the rest is petrol and aviation fuel, with minimal liquefied petroleum gas

(LPG). About one third of total fuel imported is used for electricity generation.

6.

Oil prices over the last ten years illustrate the volatility to which the Tongan economy

and electricity consumers are exposed. Between 2001 and 2004, the average price of crude oil

increased from around US$25 per barrel to around US$40 per barrel - a 60% increase. This was

followed by a dramatic and continuous rise in crude oil prices between 2004 and 2008, where the

average annual price of crude rose from US$40 per barrel to a peak of around US$140 per barrel.

In late 2008 through 2009 crude oil prices fell to 2006 levels, with the average price in 2009

being around US$62 per barrel. Diesel prices tracked the price of crude oil. Since the beginning

of 2012 the Tapis benchmark crude oil price (Singapore) has been over US$100 per barrel.3

7.

The oil price spike of 2008 led to the highest electricity tariffs Tonga has ever seen, with

electricity prices peaking at over TOP1.00 per kWh (approximately 55USc/kWh). This had a

significant negative impact on economic activity and on the quality of life for all Tongans. The

experience highlighted the risk to Tongan electricity consumers and the economy as a whole of

the combination of 100% dependency on imported diesel fuel for grid-based electricity

generation together with essentially spot market pricing of all imported fuel. The tariff as of June

2011 was TOP0.98 (almost US$0.54 per kWh at an exchange rate of TOP 1.80 per US$). This

has since reduced to TOP0.93 as at May 2012. The fuel component is TOP0.51 (US$0.28).

8.

Scenarios for future petroleum price trends indicate that on average, the price is expected

to increase. The history of international oil prices demonstrates the high price volatility that

characterizes this commodity. Acknowledging the prospect of increasing and volatile petroleum

prices, the Government recognized that the energy sector as currently structured and operated

represents a major risk to the economy overall, and to the standard of living of individual

Tongans. The Government determined that it must, as a matter of priority, take measures to

mitigate these risks. Reducing this vulnerability is an important factor in securing stable

economic growth in the short, medium and long terms.

3

International Energy Oil and Market report - 11 May 2012 (http://omrpublic.iea.org/Prices/Cr_MA_05.pdf).

2

b. Sectoral and Institutional Context

Petroleum Supply

9.

Petroleum is supplied to Tonga by two international oil companies, TOTAL and Pacific

Energy. Uata Shipping, ‘Otumotuanga’ofa and other small ferry locally owned companies are

still used for fuel distribution in the Ha’apai group of islands. Both TOTAL and Pacific Energy

have onshore storage and distribution facilities on Tongatapu, while Pacific Energy also owns

the storage facilities on Vava'u. TOTAL and Pacific Energy are active in the Tongatapu ground

product market (ADO, kerosene and gasoline), and Pacific Energy is the sole supplier of aviation

fuels across Tonga.

10.

LPG is bulk supplied by Tonga Gas (a subsidiary of Fiji Gas, 51% owned by Origin

Energy, Australia) and marketed and distributed onshore by the Government of Tonga’s (GOT)

Homegas Company.

11.

Like other small Pacific Island countries, Tonga faces a long supply chain from the

refinery source. Products are shipped from refineries in Singapore (or sometimes Australia) to

bulk storage in Fiji via medium range (MR) tankers, based on TOTAL and Pacific Energy's

regional supply schedules, and then trans-shipped to Tongatapu and Vava'u in local coastal

tankers (LCT). Thus, landed costs of product in Tonga have a relatively high freight component.

12.

The outer islands are supplied with products trans-shipped through Nuku’alofa. The

Niua's and 'Eua islands are normally the only areas for which main products (gasoline, ADO, and

kerosene) are supplied by drum. Drum distribution is more expensive than bulk distribution and

costs are compounded by the fuel losses through evaporation, leakage and drum decanting which

contribute up to 15% of total drum content.

Petroleum price regulation

13.

The Competent Authority is empowered to regulate petroleum prices under Section 5 of

the Price and Wage Control Act 1988. The Tonga Competent Authority regulates the retail price

of petroleum products, using a pricing template originally developed by the Pacific Islands

Forum Secretariat. The pricing template builds up the retail prices by taking the Singapore price

for fuel, then adding on shipping and storage fees and wholesale and retail markups. In effect,

the average price for the next month is determined by fuel prices, shipping rates and margins two

months prior.

14.

The pricing philosophy seeks to build petroleum prices for Tonga that reflect the actual

costs of buying fuels on the international market and the various costs of delivering that fuel to

Tonga and then distributing it across the country. This petroleum pricing approach is the same

as the “import parity pricing’, which is used in Australia and New Zealand, and is common

across the petroleum industry.

15.

The pricing methodology is subject to annual, triennial and ad-hoc reviews. Every year

the pricing template is supposed to be reviewed (but until recently has not been the case), using a

3

consultation process with the oil companies and other interested parties. Triennial reviews assess

regional freight rate differentials, and the overall incentives for continued investment in

petroleum supply, storage and distribution. Ad-hoc reviews of the pricing templates may be

required to deal with issues such as changes in duties, taxes, or wharfage costs.

Petroleum Safety regulation

16.

Both TOTAL and Pacific Energy state that they operate under international standards for

petroleum handling and storage and that their insurance companies require annual independent

safety audits of their facilities and safety processes. Both companies claim that international

standards are more stringent and specific than the very general safety requirements set out in

Tonga’s Petroleum Act. The model for ensuring compliance with safety standards appears to be

one of self-enforcement by the oil companies, under the oversight of internationally accredited

and independent auditors.

Key petroleum sector issues

17.

Tonga’s high dependency on imported petroleum products to meet its energy demands

makes Tonga highly vulnerable to two types of risks: 1) oil price shocks; and 2) interruptions in

the delivery of fuel. These risks pose threats to Tonga’s energy security, i.e. Tonga's access to

adequate, affordable and reliable supplies of energy.

18.

An improved understanding of these risks is required by government, together with

greater policy direction on how to mitigate risks arising from supply interruptions (e.g.

increasing the level of storage in Tonga or storing fuel offshore), oil price spikes (e.g. financial

hedging); or catastrophic events (e.g. enforcing stringent safety standards and developing

contingency plans for major fuel leaks or fires).

Electricity supply

19.

The Tonga electric system was operated by the Government prior to 1998. In 1998, it

was bought by Shoreline Electric, an investor-owned company. The Government of Tonga

bought the assets back from Shoreline in July 2008. The current company, Tonga Power

Limited (TPL) is a vertically-integrated state-owned enterprise, wholly owned by the

Government of Tonga and operated at arm’s-length. TPL serves four island group grid systems

in Tonga. The main island of Tongatapu in the southern island cluster is the largest with some

73% of the Tonga population living there4. Other systems are on ‘Eua, also in the southern

cluster, Ha’apai in the central cluster and Vava‘u in the northern cluster. Each of these centres

has a diesel power station and a medium/low voltage distribution system. Tongatapu has a small

11kV network. The four island group grids have a generation capacity of just over 13MW that

supplies around 20,000 customers. Tongatapu has the largest share with generation capacity of

11MW and around 15,000 customers.

20.

4

Table 1 below summarizes the generating capacity, recent peak and energy demands on

Tonga National Population and Housing Census 2011.

4

each grid.

System

Tongatapu

Ha’apai

Vava’u

‘Eua

Total

Table 1: A Summary of the TPL Grid Systems 2011 (source TPL)

Installed Capacity

Peak Demand

Annual Energy

Annual

kW

kW

Supplied kWh

Load Factor

11,280

8,150

47,035,950

67.5%

772

296

1,373,698

60%

1,272

892

4,823,910

61-63%

373

285

1,056,588

50-55%

13,697

9,623

Electricity price regulation

21.

The Electricity Act 2007 provides the governance framework for the grid-connected

electricity sector in Tonga. In accordance with the Act, the Electricity Commission was

established in 2008 as the regulatory agency for grid-based electricity supply. The Act defines

the role of the Electricity Commission in regulating the generation and selling of electricity, and

establishes the role of a concessionaire in producing, delivering, and retailing electricity.

22.

The Electricity Concession Contract (ECC) entered into between the Kingdom of Tonga

and TPL under section 20 of the Electricity Act 2007 (extended under the Electricity

Amendment Act 2010) gives TPL exclusivity for the supply of electricity to the island groups.

The ECC sets out the conditions for the utility’s operations, including specific details as to how

and the frequency at which the tariffs are to be calculated, outlines operational efficiency

benchmarks, consumer service standards and penalties for non-compliance, and regulatory reset

provisions at the end of each regulatory period. The current ECC regulatory period runs until

June 30, 2015 at which point the ECC schedules and conditions are renegotiated for a further

seven years.5

23.

The ECC distinguishes fuel and non-fuel components of the tariff. Changes in fuel prices

are fully passed through into power prices, via a clearly defined pass-through mechanism set out

in the Concession Agreement. Although the ECC allows TPL to treat the four island grids

individually, in May 2009 TPL chose to standardize tariffs across all grids and consumer classes.

Tariffs are allowed to be adjusted every three months, the latest being a 6.6% decrease effective

April 2012. The non-fuel tariff component follows the Consumer Price Index (CPI), while the

fuel tariff component is adjusted so that the Concessionaire recovers only the permitted fuel

costs. The ECC requires that TPL earn a rate of return (currently set at 12.9 %) of its Regulated

Asset Value (RAV). TPL is required to submit capital expenditure plans to the Commission for

approval and the Commission can deny approval of a capital expenditure that is not in line with a

least-cost supply strategy. The overall tariff structure is designed to ensure that TPL operates

using full commercial standards. A fuel component increase was made on June 1, 2011 to bring

the tariff to TOP0.98 but TPL Board deferred the 6.7% annual adjustment to the non-fuel

component, which reduced the tariff impact by some TOP2.7 per kWh. Subsequently, in April

2012, TPL applied the above increase in non-fuel component, in addition to the allowable CPI

5

Section 9.2 of the ECC.

5

movement for the year ending December 2012. The increase in non-fuel component was 8.3%.

The total (combined fuel and non-fuel) tariff currently sits at TOP0.93/kWh.

24.

The role and effectiveness of the electricity commission is currently under a broader

regulatory review by the Asian development bank, as part of a multi-region assessment of

regulation in small island states.6

Tonga Power Ltd. Performance

25.

TPL inherited its database and data management systems from its predecessor. A

significant amount of data was lost during the 2006 civil disturbance. The Supervisory Control

and Data Acquisition (SCADA) system at the power station on Tongatapu that automated data

collection on the generating units had failed. The electricity billing database system was over 15

years old, it had certain limitations and TPL only has consumption data by customer back to

when it acquired the business in 2008. Electricity sector data are quite limited at present.

26.

Overall technical and non-technical losses have been high in recent years. On the

Tongatapu grid, where approximately 85% of all of the grid-supplied energy is consumed, total

losses represented just over 17.5% of the energy generated at the engine-generators in 2009

while on the three smaller grids, recent total losses have been between 12.5% and over 20.0% of

generated energy. Based on the total losses and TPL’s estimate that technical losses are in the

order of 12% on Tongatapu, non-technical losses are running around 3%, with station service

around 2-3%. However, over the past year TPL has taken a number of steps to improve data

gathering and reduce losses; at March 2012 the twelve month rolling average total loss has

reduced to under 15%, the effect of recent revenue protection projects will bring total losses

down to the target of 12% by the end of 2012.

(i)

TPL commissioned two new 600kW diesel electric generators on Vava’u and the

implementation of the data collection functions for the SCADA system supplied with the

new generators.

(ii)

TPL has completed the installation and commissioning of a new, computerized

customer accounts system. Current day’s receivable stands 12 days.

(iii)

TPL has installed more than 18,500 new meters as of mid March 2012 and all of

these units can be read with a portable electronic reader. All meter readers will be using

a handheld reader by 3rd quarter of 2012.

(iv)

TPL has installed Light-Emitting Diode (LED) street lights along the whole of the

waterfront in Nukualofa and along the road from the airport to the central business

district (CBD). The trials were considered successful and the plan is now to extend the

LEDs to all street lights. It is now a requirement that any new street lights be LED.

(v)

TPL replaced all of the low voltage (LV) connections around the Popua village, as

a trial to determine loss reduction. Measures show a loss reduction from 8.23% to 7.1%.

6

ADB RETA 6424 “Effective Regulation of Water and Energy Infrastructure Services: Small Island Countries”.

6

TPL is continuing to change connectors on the LV networks serving Nuku’alofa and

reports that, as at May 2012, the majority had been changed. TPL has completed a similar

program to change the LV connectors on all of ‘Eua and has found that losses may have

been reduced by more than 5%.

(vi)

TPL conducted a trial in two villages on Tongatapu by replacing meters to see if

non-technical losses can be reduced. TPL staff found a loss rate of over 50% in one and

over 20% in a second village. After all meters were replaced, the losses were measured

at about 7.5% and 9.5%.

(vii) TPL has installed new electronic metering on all fuel tanks and upgraded the

station service metering so that a more consistent estimate of parasitic load at each station

can be maintained. A monthly stock take of fuel and reconciliation of fuel used provides

assurances as to loss of fuel from leakage or theft.

(viii) TPL has repaired the SCADA data collection system serving the older Caterpillar

generation units and linked the data collection component of the MAK SCADA to the

plant control room at the Popua power station.

(ix)

Other work has included upgrading insulators on many of the high voltage (HV)

lines, the clearing of vegetation that is encroaching on the HV lines and seeking to

standardize as many of the LV lines as possible.

(x)

Overall loss reductions achieved over the past 18 months as of April 2012 on

Tongatapu: 3.2%, on Vava’u: 4%, on Ha’apai: 2.7%, and on ‘Eua: 1%.

(xi)

A 1 MW solar power plant is under construction near the Popua diesel generating

station and is scheduled to be commissioned before the end of August 2012.

Key electricity sector issues

27.

All grid-connected electricity generation in Tonga is from imported diesel oil. The

Tongan economy and electricity consumers have been exposed to high and volatile electricity

prices over the last ten years due to inter alia fluctuations in the price of oil internationally. The

cost of automotive diesel oil (ADO or “diesel”), the fuel used in all of TPL’s diesel generator

sets, has varied widely during recent years. In Table 2 and Figure 1, the total energy generated,

the fuel used and the total cost of that fuel are shown for calendar years 2005 through 2011.

28.

Although annual electric demand grew by just 2% in the six years, the annual fuel cost in

TOP increased by almost 175% in the same period. From 2010 to 2011, although the demand

was declined, the fuel use increased. This means the energy intensity could be showing some

sign of increase and thus needs to monitor carefully this symptom.

7

Table 2: Recent Fuel Use and Cost for Electricity Generation7

Year

kWh

ADO, litre

Fuel cost, TOP

Fuel cost, UST

2005

51,557,573

13,132,596

13,015,693

6,671,978

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

55,281,157

56,434,346

56,777,701

52,631,366

52,623,212

13,921,617

14,115,388

14,186,248

13,188,831

13,086,288

17,006,525

19,527,073

28,527,236

28,033,960

30,541,979

8,198,466

9,411,998

13,750,053

13,805,090

15,997,379

2011

52,579,016

13,111,463

35,751,813

20,654,418

Source: TPL generation table, prices from Ministry of Labor, Commerce and Industry and National Reserve Bank.

Figure 1: Recent Fuel Use and Cost for Electricity Generation8

60,000,000

50,000,000

40,000,000

ADO, litre

kWh

30,000,000

Fuel cost, TOP

20,000,000

Fuel cost, USD

10,000,000

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

Source: TPL generation table, prices from Ministry of Labor, Commerce and Industry and National Reserve Bank

29.

Figure 2 illustrates how the cost per unit of electricity on Tongatapu has varied since

March 2002. The cost of diesel fuel drove the tariffs to record highs during 2007 and 2008. The

tariff for Tongatapu reached 102.67 seniti (US$0.5659) and 104.67 on Vava’u (US$0.576).

Since mid-2008, international oil prices have fallen significantly and the correspondingly lower

diesel fuel costs have been passed on to customers through the tariff changes in February and

May 2009, and more recently in April 2012. Average prices though now are high and sustained

at those levels. In addition, the tariff structure changed in May 2009 to equalise the tariff across

all grids. By late 2009, tariffs once again had to be increased due to increasing fuel oil costs. As

discussed above on electricity price regulation, a fuel component was increased in June 2011 to

The cost of shipping fuel to the grids on Vava’u, Ha’apia and ‘Eua has not been included here.

The cost of shipping fuel to the grids on Vava’u, Ha’apia and ‘Eua has not been included here.

9

The official exchange rate floated prior to April 2006 when the rate was fixed at TOP 2.075/US$ until late July

2009. The average monthly exchange rate of the TOP$ has since appreciated to 1.82/US$.

7

8

8

bring the tariff to TOP0.98 but TPL Board deferred the 6.7% annual adjustment to the non-fuel

component, reducing the tariff impact by some TOP2.7 per kWh. As discussed above, fuel and

non-fuel components of tariff were adjusted in April 2012, with overall net effect that the tariff

as at May 2012 sits at TOP0.932/kWh

Figure 2: Electric Rates History in Tonga

1.200

1.000

0.800

0.600

0.400

0.200

Jul-11

Jan-11

Jul-10

Jan-10

Jul-09

Jan-09

Jul-08

Jan-08

Jul-07

Jan-07

Jul-06

Jan-06

Jul-05

Jan-05

Jul-04

Jan-04

Jul-03

Jan-03

Jul-02

Jan-02

-

Pa'anga

US$

Source: National Reserve Bank of Tonga

30.

Table 3 shows the medium term demand forecast for Tongatapu, taking into account both

increases in efficiency of supply and end use, as per the TERM. Figure 3 shows the combined

high, median and low forecasts for the four grids combined. Improvements in efficiency could

reduce demand growth by about 17% overall compared to a “do nothing” approach. Even at the

modest rate of demand growth projected taking into account improved supply and end use

efficiency, demand is expected to increase by nearly 30% over 2010 - 2020. Subsequent reviews

by TPL have shown that demand continues to be flat, with total generation growing at 0.25% per

annum to 2020. Energy generated across all grids for the year ending June 2013 is budgeted at

approximately 53GWh.

31.

Reducing the vulnerability of the country to future oil price shocks is a key issue which

requires actions to improve the petroleum supply chain and price risk management, increase

efficiency of generation, distribution and use of electricity, and diversify away from diesel-only

electric generation. It is important that a programme-planned approach is adopted that will

ensure risk mitigation on the management, distribution and storage of petroleum is undertaken

involving the use of credible external expertise before major changes are implemented. Without

taking action, the Tongan economy and energy consumers will be increasingly exposed to risks

associated with the growing dependency on imported petroleum for electricity generation and

transport.

9

Table 3: Median Forecast, Loss Reduction plus DSM Implemented on Tongatapu

end of

end of

end of

end of

end of

end of

end of

end of

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

2020

Median Growth Scenario, kW.h

~Actual

Annual Growth Rate, Billed Energy

-7.82%

1.00%

2.00%

3.00%

4.00%

4.00%

5.00%

5.00%

Billed Energy

7,012,005

37,382,125

38,129,768

39,273,661

40,844,607

42,478,391

44,602,311

56,925,107

1.667%

5.00%

8.33%

10.00%

10.00%

10.00%

10.00%

DSM effect ,% of Billed

Impact of DSM on Billed, kW.h

0

623,160

1,906,488

3,272,674

4,084,461

4,247,839

4,460,231

5,692,511

Net Billed Energy

37,012,005

36,758,965

36,223,279

36,000,986

36,760,146

38,230,552

40,142,080

51,232,596

Technical Losses (est.)

5,284,297

4,701,728

4,139,803

3,650,804

3,273,024

3,170,029

3,086,157

3,323,195

Loss as % Sent Out

12.00%

11.00%

10.00%

9.00%

8.00%

7.50%

7.00%

6.00%

Non-Technical Losses (est.)

1,739,510

1,282,289

1,034,951

912,701

879,625

866,475

859,715

830,799

Loss as % Sent Out

3.95%

3.00%

2.50%

2.25%

2.15%

2.05%

1.95%

1.50%

Total Network Losses

7,023,807

5,984,018

5,174,754

4,563,505

4,152,649

4,036,504

3,945,872

4,153,994

Energy Sent Out

15.95%

14.00%

12.50%

11.25%

10.15%

9.55%

8.95%

7.50%

Energy Sent Out from Popua

44,035,812

42,742,983

41,398,033

40,564,492

40,912,795

42,267,056

44,087,951

55,386,591

Add Station Service

898,690

872,306

844,858

827,847

834,955

862,593

899,754

1,130,339

Station Service Rate, % Generated

2.00%

2.00%

2.00%

2.00%

2.00%

2.00%

2.00%

2.00%

Total, Energy Generated

44,934,502

43,615,288

42,242,891

41,392,339

41,747,750

43,129,649

44,987,706

56,516,929

Annual Peak Demand, kW

8,142

7,903

7,654

7,500

7,565

7,815

8,152

10,241

Figure 3: Energy Forecasts, Sum of All Grids

85,000

80,000

MegaWatt.hours

75,000

70,000

65,000

60,000

55,000

50,000

45,000

40,000

2010

2011

2012 2013 2014

Do Nothing Median

Efficient Low

2015 2016 2017

Efficient Median

2018

2019

2020

Efficient High

Source: Report on The Tonga Electric Supply System: A Load Forecast, prepared by Martin Swales for the World

Bank / ASTAE, January 2010

10

Government Strategy in the Energy Sector: The Tonga Energy Roadmap (“TERM”)

32.

In April 2009, the Government and Development Partners with the coordination of the

World Bank (WB), embarked on a process to undertake a sector-wide review and develop an

approach to improving the performance of the energy sector and to mitigating the risks. The

resulting document entitled the “Tonga Energy Road Map 2010-2020: Ten Year Road Map to

Reduce Tonga’s Vulnerability to Oil Price shocks and Achieve an Increase in Quality Access to

Modern Energy Services in an Environmentally Sustainable Manner”, or “Tonga Energy Road

Map (TERM)” addresses improvements in petroleum supply chain and consideration of price

hedging instruments, increased efficiency both in electricity supply and use, development of

grid-connected renewable energy resources, improved access to quality electricity services in

remote areas, reduced environmental impacts both locally and globally, enhanced energy

security, and overall sector financial viability. The scope includes policy, legal, regulatory and

institutional aspects of the sector as well as investment. It covers a ten year time period. As

technologies, costs, demand for electricity and sources of financing change over time, it is

envisioned that the TERM will be periodically updated to take these factors into account. The

next TERM review is expected to be completed before the end of 2012.

33.

The TERM focuses on reducing cost and volatility in the price of petroleum imports and

de-linking electricity production from petroleum in accordance with government policy with

respect to energy security and renewable energy goals. A further set of actions could focus

around use of petroleum for transport applications. This was beyond the scope of the TERM

exercise, but work is already underway in this area and would complement the TERM.

34.

Development of the TERM involved unprecedented information-sharing by Government

Ministries and Tonga Power Limited (TPL), and set a new standard in the Pacific for

Government leadership and coordinated development partner support. The process has benefited

from the active participation of more than fifteen development partners, including multi- and bilateral agencies and regional organizations responsible for energy in the Pacific, over the course

of one year. The TERM is important not only for the expected impact on the energy sector in

Tonga. It is already being cited as an example in other Pacific Island Country (PIC) energy

sector discussions and is expected to serve as a model for Government leadership and

development partner coordination of sector-wide planning applicable to infrastructure more

broadly.

35.

The TERM sets out priority actions in the areas of policy, legal, regulatory and

institutional arrangements, and sets out an investment program based on a least cost approach for

reducing reliance on diesel for power generation, with explicit consideration given to managing

risk through development of a portfolio of options to meet the demand for electricity. The

TERM also recommends a detailed program of actions with indicative funding sources and costs

for each element. The TERM will serve as the guiding document for Government and

development partner support.

36.

GOT formally adopted the TERM in August 2010 and by doing so, committed to key

principles for the energy sector and an indicative implementation plan. The Bank will provide

on-going support to the GOT in implementation of the TERM in the form of this project. Other

11

development partners are also working with GOT preparing support for specific aspects of

TERM implementation (see Annex 4).

Objective of TERM

37.

The objective of TERM is to lay out a least cost approach and implementation plan to

reduce Tonga’s vulnerability to oil price shocks and achieve an increase in quality access to

modern energy services in a financially and environmentally sustainable manner. The TERM

will serve as the guiding document for Government actions and development partner support. It

covers a ten year time period. It is envisioned that the TERM will be periodically updated. The

TERM considers the full range of options to meet the objective, including:

Improvements in petroleum supply chain to reduce the price, and consideration of price

hedging instruments to reduce price volatility of imported petroleum products;

Increased efficiency of conversion of petroleum to electricity supplied to consumers (i.e.

increases in efficiency and reduced losses);

Increased efficiency of conversion of electricity into consumer electricity services (i.e.

end-use efficiency measures);

Replacing a portion of current or future grid-based generation with renewable energy.

38.

In addition, in order to meet the objective of increasing access to good-quality electricity

supply, the TERM includes recommendations for a new approach to meeting the needs of

consumers too remote to be connected to a grid-based supply.

Principles underpinning the TERM

39.

Flexibility to update and adjust the implementation plan is needed to ensure the TERM

remains relevant and responds to evolving circumstances. Recognizing the need for on-going

adjustments, the TERM sets out the key principles that will be adhered to, as the specifics of the

implementation plan are updated.

40.

The key principles of the TERM are set out below:

41.

Least Cost Approach to Meet the Objective of reducing Tonga’s vulnerability to oil

price increases and shocks. To identify the least cost approach, the full range of options must

be considered and evaluated relative to one another rather than being considered in isolation.

These include improvements in the petroleum supply chain efficiency; supply and demand side

efficiency improvements; and options for non-diesel power generation for both grid and off-grid

electricity supply. The selection of each new investment will be based on the principle of the

lowest lifecycle cost among the technically feasible alternatives.

42.

Managing Risk. The introduction and implementation of new technical and institutional

approaches will be designed and managed to avoid inadvertently increasing interruption risks in

12

the effort to address price risk issues. The sequencing and timing of adjustments will allow

sufficient time to undertake the detailed work and get in place the required specialist expertise.

An important element of managing risk is to develop a portfolio of options to meet the demand

for electricity. The value of establishing a portfolio of supply sources will be considered when

evaluating alternatives with comparable cost characteristics.

43.

Financial Sustainability. In this context “financial sustainability” means that the cost of

operating the energy sector, including regulatory, operations, maintenance, fuel and financing

costs are recovered through the tariff. While the provision of a subsidy for a particular

investment is not incompatible with the concept of financial viability, it should be applied in

cases where there are specific objectives outside the normal commercial operation. For example,

to address specific social or equity objectives related to providing electricity services in remote

areas, to address specific negative externalities including funds aimed at supporting a transition

to renewable energy to reduce green house gas (GHG) emissions, or to support gaining

experience with technologies that may be expected to become more cost effective over time.

The essential feature is that the source of any subsidy required to keep the sector financially

viable must be secure. Continued dependence on significant injection of subsidy to meet the cost

of normal operations and expansion would not be considered a financially sustainable situation.

Investment options must be evaluated considering the cost implications over the investment

lifetime, to avoid substituting short term price relief for continuing high prices in the medium to

long term.

44.

Social and Environmental Sustainability. Environmental and social sustainability

encompasses both minimizing local negative social and physical environmental impacts of the

energy sector, as well as aligning with global goals with respect to minimizing impact on climate

change where possible. New energy investments under the TERM would be subject to

Environmental and Social Impact Assessments and Mitigation Plans as necessary, as per

international practice. Special consideration will be given to those groups with specific needs

including youth, women, religious groups and those with special needs. Investments that have

major negative environmental or social impacts or constraints that cannot be mitigated or solved

will be avoided. As one of the group of countries which has contributed least to global climate

change, yet stands to be severely impacted, Tonga is committed to setting an example for larger

countries with respect to responsibly and sustainably reducing GHG emissions. Social

sustainability also incorporates an element of equity. Hence the scope of the TERM includes the

provision of sustainable, affordable electricity supply that meets the needs of people living in

remote areas.

45.

Clear, appropriate and effective definition of roles for Government, TPL, and the

Private Sector. GOT is responsible for strategic direction in the energy sector (policy and legal

framework), sector oversight (regulation), creating an enabling environment and monitoring of

progress to achieve the strategic goals, and facilitating where possible the direction of financial

assistance to the sector in accordance with the principles listed above. This implies a strong role

in supervising the implementation of the TERM and actions to revise policy, legal and regulatory

arrangements. For projects and investments that have as a major goal the testing and gaining

experience with technologies new to Tonga, to the extent that public sector funding is available

ownership should remain with Government, possibly but not necessarily through TPL.

13

46.

TPL will be an important implementing agency for the early TERM activities, including

in improved network and efficiency, and implementation of the off-grid program. TPL will also

have responsibility of maintaining supply of electricity to customers on the four grids. TPL is a

key source of technical expertise in the energy sector and this role will be strengthened through

training as part of the implementation of the TERM.

Phases of TERM

47.

The TERM has three phases of implementation: Phase 0, Phase 1 and Phase 2. Phase 0

required the GOT to undertake major institutional governance reform of the energy sector. In

addition, it requires that the utility, Tonga Power Limited (TPL), be provided with support to

enable it to manage the current infrastructure in a safe and operationally sound manner. The

TERM recommended (and Cabinet approved) the conduct of an independent Electricity Tariff

Review under Phase 0 of the TERM to address the key weaknesses of the existing tariff, by

providing recommendations for a new tariff regime that is consistent with a financially

sustainable and efficient electricity sector, taking into account the planned shift to renewable

energy sources and energy efficiency, while providing protection for the poorest consumers.

This review will be shortly commenced under support from the Pacific Infrastructure Advisory

Center (PIAC).

48.

Phase 1 includes works designed to implement the first set of proof-of-concept renewable

energy projects, including on-grid Solar PV supply and substitution of a portion of the fuel used

in existing diesel engines with coconut oil; and the scaling up of the end-use efficiency activities

and review of initial experience with petroleum financial risk management. By the completion

of Phases 0 and 1, a private sector investment framework within the energy sector will be in

place. In addition, Phase 2 will involve further efficiency and renewable energy investments and

will be initiated when data and experience from the phase 0 and phase 1 activities have been

evaluated.

c. Higher Level Objectives to which the Project Contributes

49.

The Tonga Energy Road Map (TERM) represents the result of a year of intensive dialog

with the Government, and consultation and coordination with energy sector development

partners. The TERM has now been operational for two years. The World Bank played a major

role in development of the TERM, from the initial conception of the scope and approach,

through support for and supervision of the key analytic work, managing the coordination of longterm energy sector development partners as well as helping to bring on board new players, and

synthesis of the inputs into the final TERM document. The proposed project forms an integral

part of the Bank’s overall energy sector engagement in Tonga: beginning with the intensive

technical assistance (TA) and dialog around development of the TERM, an Energy Sector

Development Policy Operation (DPO) that was completed in FY11, and the first in the

programmatic series of two DPOs which include a focus on key actions in the energy sector that

was completed in FY12, with the second proposed for FY13.

50.

The approach set out in the TERM is fully in line with the institutional agenda on Climate

Change. Driven by energy security, the TERM integrates energy efficiency and renewable

14

energy generation into the mainstream sector planning and policy framework, through the focus

on reducing vulnerability to oil price rise and shocks as a key factor in enhancing national energy

security. The GOT also recognizes the importance of seeking for climate finance associated to

clean energy investments given the important contribution to support their sustainability.

II.

PROJECT DEVELOPMENT OBJECTIVES

a. PDO

51.

The Project Development Objective (PDO) is to support the strengthening of the

institutional and regulatory framework of the Tonga Energy Roadmap.

52.

The TERM sets out a ten year road map to reduce Tonga’s vulnerability to oil price

shocks and achieve an increase in quality access to modern energy services in an

environmentally sustainable manner. The proposed project will provide assistance to strengthen

the core institutions and regulatory framework relating to TERM and it is a key precursor for the

ongoing and planned operations under the Energy Roadmap (see Annex 4).

b. Project Beneficiaries

53.

Direct beneficiaries of this project are TERM-IU and TPL, and indirectly energy

consumers (households and businesses). The project’s support to TERM implementation is

expected to lead to more efficient use and targeting of available resources which will in turn lead

to lower, more stable electricity tariffs, improved quality of electricity service and improved

access to affordable electricity. The project’s assistance to a sector structure and institutional

arrangements to coordinate strategic planning and targeting of resources will set in motion

actions to improve the efficiency, cost-effectiveness and transparency of the sector institutions,

investments and operations. Support for the development of robust process and financing

mechanisms and investment in renewable energy will improve the effectiveness and rate of

diversification from diesel-based power generation. Improved petroleum price risk management

will contribute to electricity price stability, including all petroleum end users and facilitate

planning and management of Tonga’s balance of payments situation.

54.

Reducing the vulnerability of the economy to oil price rises and shocks will improve the

macroeconomic stability which will have positive implications for the general public. Benefits

with respect to the energy sector aspects also extend beyond Tonga. The process of developing

and now implementing the TERM is widely seen in the region as a concrete example of a new

paradigm for Government leadership and development partner coordination to undertake sensible

planning followed by coordinated implementation.

c.

55.

PDO Level Results Indicators

Progress will be measured against the following results indicators:

(i)

Sector structure and institutional arrangements operate to coordinate strategic

15

planning and targeting of resources to implement TERM.

(ii)

TPL system is more robust with respect to accepting energy supply from

intermittent sources and delivers quality electric power. Internationally-recognized

network reliability criteria such as the System Average Interruption Duration Index

(SAIDI) is currently monitored by TPL management. TPL will seek to track SAIDI

minutes saved as a measure of the success of the project.

III.

PROJECT DESCRIPTION

a. Project Components

56.

The Project will consist of two components:

57.

Component 1: Strengthening the Energy Sector Framework and Structure

(AusAID/PRIF US$0.70 million; ASTAE US$0.40 million; GOT US$ 1.00 million.

Implementing Agency: TERM-IU). This component will support the GOT to strengthen the

functioning of the TERM-IU including through technical assistance in the areas of: (i) energy

sector policy; (ii) environmental and social safeguard frameworks; (iii) petroleum price risk

management strategy; (iv) feasibility studies for power generation from renewable sources; (v)

detailed surveys for electricity use; and (vi) development of a communication plan (including

awareness and dissemination material in local language) for the Energy Roadmap in order to

rally key stakeholders around long-term goals and activities being implemented, thus mitigating

risks of misinformation.

58.

Component 2: Preparing TPL for Renewable Energy Supply (AusAID/PRIF

US$1.80 million; TPL US$0.10 million. Implementing Agency: TPL). This component will

support TPL to strengthen its capacity to: (i) carry out power system modeling to determine the

most cost effective way to diversify energy generation, with a focus on achieving a high longterm renewable and distributed energy penetration; (ii) design and specify upgrades to monitor,

control, and protect systems to ensure a reliable and secure supply of energy through the

electricity system with high levels of renewable energy generation; (iii) develop standards and

procedures for connection to the power system by independent power producers; and (iv)

develop (in conjunction with TERM-IU and to be approved by TERM-C) a power system plan

for a period of five years focusing on specific renewable energy technology projects such as

solar, wind, biomass and biofuels, but also covering energy storage options and demand side

management.

b. Project Financing

Instrument

59.

Financing will be provided by AusAID through the Pacific Region Infrastructure Facility

(PRIF), the Asia Sustainable and Alternative Energy Program (ASTAE)10, GOT, and TPL.

10

ASTAE Grant agreement will end December 31, 2014 in line with the Parent Trust Fund.

16

Retroactive financing of up to 20% of the grant funding is included.

Project Cost and Financing

Table 4. Project cost per source of finance

Project cost

AusAID/PRIF

ASTAE

Financing

% Financing

Component 1: Strengthening the

Energy Sector Framework and Structure

2.10

1.10

52%

Component 2: Preparing TPL for

Renewable Energy Supply

1.90

1.80

95%

Total Project Costs

4.00

2.90

72%

Project Components

c. Lessons Learned and Reflected in the Project Design

60.

Lessons learned during the development of TERM-A are reflected in the design of this

operation. The TERM has strong government ownership and is the best example of development

partner harmonization in any sector in Tonga. Every aspect of the TERM program is customized

for Tonga. A key lesson learned is the importance of a “whole-of-sector” approach as opposed to

isolated and disconnected interventions. Both technical assistance and investment support are

more effective when there are real plans and opportunities to put it into practice.

61.

Another important lesson is information sharing and coordination with other development

partners from an early stage, as well as the proper identification of the stakeholder groups and

their representatives. Moving forward with a “whole-of-sector” approach requires a strong

development rationale and perceived domestic benefits for which a communicating adequately

with the different stakeholders and constituencies becomes essential.

IV.

IMPLEMENTATION

a. Institutional and Implementation Arrangements

TERM Governance Structure

62.

TERM. In April 2010, the main report of the Tonga Energy Road Map 2010-2020

(TERM) was completed and published. In June 2010, the Tonga Petroleum supply report was

submitted to the GOT. This petroleum report and recommendations are a critical component of

the TERM. The TERM was then approved under Cabinet Decision 739 of 20thAugust 2010.

63.

TERM-Agency (TERM-A). On April 20 2012, Cabinet approved the TERM-Agency

17

(TERM-A) as an inherent body responsible for energy matters under TERM.11 As a Government

Agency, TERM-A will act on behalf of Cabinet, and shall be accountable directly to Cabinet, in

accordance with the mandate given to it by Cabinet. TERM-A is responsible of achieving the

objectives of TERM on behalf of the Government. All energy related projects detailed under the

TERM will be the responsibility of the TERM-A.

64.

TERM-Committee (TERM-C). Within TERM-A there is the Tonga Energy Road Map

Committee (TERM-C) which is the governing entity within TERM-A, and, as approved by

cabinet, have the following mandate:

(1)

Consider the proposed institutional reformation and all energy sector related

projects, taking into consideration the whole of Government institutional rationalization

programme;

(2)

Coordinate on Ministry cross cutting energy sector related issues ensuring an

integrated approach to the energy sector reformation program as outlined in TERM;

(3)

Approve projects for the energy sector as detailed under the TERM, taking into

account the equitable distribution of development benefits and environmentally

sustainable development of the energy sector;

(4)

Monitor the progress of the TERM implementation and meet with the GOT

Development Partners annually to review the TERM;

(5)

Oversee and approve the operation of TERM-IU, in particular to budget, staffing

and TERM-IU program implementation of TERM;

(6)

Determine own operational procedures and TERM-IU operational procedures

(based on Government regulations) as approved by cabinet;

(7)

Convene at least once a month or more if needed; and

(8)

Report at least once a month to Cabinet on the progress of TERM.

65.

TERM-C is a dedicated and collective policy management and oversight organisation

(whilst independent of discreet energy related Ministries) in order to be able to support the

achievement of TERM objectives. TERM-C is acknowledged as crucial to the success of TERM

and continued Development Partner funding.

66.

The members of TERM-C are:

(1)

(2)

(3)

(4)

11

Prime Minister

Minister of Environment & Climate Change

Minister for Finance and National Planning

Chairperson Public Service Commission

Cabinet Decision No. 330.

18

Chair

Alternate Chair

Member

Member

(5)

(6)

(7)

(8)

(9)

(10)

(11)

(12)

Secretary for Foreign Affairs

Director of Environment & Climate Change

Secretary for Finance and National Planning

Secretary for Labour, Commerce & Industries

Director for Public Enterprises

Secretary for Transport

Solicitor General

Secretary (to be appointed by TERM-C) Member

Member

Member

Member

Member

Member

Member

Member

67.

The role of Secretary is to be responsible for keeping a regular oversight on the

performance of the Director of TERM-IU, facilitating Sub-Committee work commissioned by

TERM-C, and working with individual TERM-C members on matters directed and required by

TERM-C.

68.

TERM Implementation Unit (TERM-IU). TERM-IU is the operating entity under TERMC directly implementing TERM. The Implementation Unit was given the following mandate by

TERM-C:

(1)

Implement TERM objectives as detailed in the TERM document, endorsed by

TERM-C and approved by Cabinet;

(2)

Source development partner funding for the operation of TERM-IU and TERM

projects for a period of not less than 5 years (3 years remaining from April 2012);

(3)

Recruit appropriate staff for TERM–IU (local and overseas technical expertise);

(4)

Coordinate the projects and different phases of TERM implementation;

(5)

Provide secretariat services to TERM-C;

(6)

Report at least once a month to TERM-C on the operation of TERM-IU (financial

and program management);

(7)

Comply with Government financial management and procurement regulations;

and

(8)

Transition the TERM-IU, upon completion of TERM implementation, to a

Ministry the Government decides upon.

69.

The interim TERM-IU Director was appointed in February 2012 for a period of six

months. The substantive TERM-IU Director will be appointed by July 2012 for a term of two

years, and will be responsible for inter alia; quality, relevance, and coherence of the work of the

Unit as well as recruitment of key personnel for the IU; design and implementation of the Unit’s

work program for the first two years; and monitoring and regular reporting of the Unit’s

activities and outputs to the TERM-C. The Director of TERM-IU is not a Member of TERM-C

but presents and reports on relevant matters to TERM-C during its normal meetings and provides

19

secretariat support services, through the TERM-IU, at TERM-C meeting.

Tonga Power Ltd (TPL)

70.

TPL’s organizational structure is in accordance with the Public Enterprise Act 2003. It

establishes a Board that reports to its shareholder the GOT through the Ministry of Public

Enterprise (MPE). The MPE oversees all of GOT’s shareholdings and monitors the performance

of the State Owned Enterprises (SOEs). Tonga's SOEs and TPL in particular have performed

comparatively better than those of other Pacific countries because this governance structure

generally allows them to operate independently of the political process, with fewer unfunded

Community Service Obligations (CSOs).12

71.

As part of TPL’s recognition of the importance of coordinating the implementation of

donor-funded projects, all donor-funded projects generally fall directly under the responsibility

of the CEO with day-to-day management of projects expected to fall under the proposed

‘Strategic Initiatives’ unit.

b. Results Monitoring and Evaluation

72.

Annex 1 sets out the Results Framework and indicators that will be used to monitor and

evaluate the project.

c. Sustainability

73.

Preceding the preparation of this project, the GOT and TPL have undertaken a number of

actions demonstrating commitment to working with the WB and other Development Partners

(DPs) to begin to address key energy sector issues. The development of the TERM is a clear

example of strategic focus and thinking in this regard. The setting up of the TERM-C and the

TERM-IU, together with the periodic TERM-Coordination meetings and follow up, provide

enough comfort level of the GOT’s commitment towards the sustainability of the program.

V.

KEY RISKS AND MITIGATION MEASURES

74.

The 2010 national elections under the new constitutional arrangements proceeded

smoothly. The new administration has made transparency and good governance a centrepiece of

its platform and has affirmed its commitment to implement the TERM. One major pressure

point for the new government – the budget gap – is being partly addressed by a series of WBfunded budget support operations which include a strong focus on implementing key aspects of

the TERM. The TERM features prominently in the GOT’s dialog with other development

partners, both traditional and new partners that have been attracted to provide support to Tonga

in part because of the GOT’s commitment to the TERM. Both the previous and current

administrations have enthusiastically adopted the TERM and it has gained regional prominence.

12

Finding Balance 2011: Benchmarking the Performance of State-Owned Enterprises in Fiji, Marshall Islands,

Samoa, Solomon Islands, and Tonga. ADB, 2011.

Performance Benchmarking for Pacific Power Utilities” Pacific Power Association 2011, December 2011.

20

The risk of developments at the country level disrupting the GOT’s efforts to implement the

TERM is considered low. The proposed WB project is fully aligned with the TERM and

consequently the risk from events at the country level is considered low.

Implementation risks

75.

Risk associated with stakeholders is considered to be moderate to low. In any project

involving a shift in institutional authority and/or a revision to laws and regulation, some

individual stakeholder interests will inevitably not be fully met. Implementation of the TERM

will involve such changes. Mitigation of stakeholder risk is an early and continued effort at

building broad stakeholder support. Within the GOT this process is underway with respect to the

institutional changes to strengthen the TERM-IU, which are being managed as an integral part of

the overall civil service reform program. The TERM-IU, with assistance from REEEP, will

actively engage in consultation with respect to proposed changes in the policy, legal and

regulatory structure, with inputs from Parliament, business associations, and a broad range of

government stakeholders.

76.

Risk associated with the GOT’s commitment to implementing the project is considered to

be low. The GOT has taken a number of actions, including Cabinet approvals and made high

level commitments with traditional and new development partners associated with the TERM

implementation.

77.

Risk associated with implementing agencies’ capacity is considered to be moderate. The

GOT has taken a number of actions to strengthen implementation capacity, including sourcing

and allocating new bi-lateral funds to the restructuring of the TERM-IU, appointing a high level

TERM-IU interim Director and three core support staff, partnering with REEEP and obtaining

Cabinet approval of TERM-A as a Government Agency responsible of achieving the objectives

of TERM on behalf of the Government. TPL management has demonstrated willingness and

ability to implement technical improvements. More details follow in the section below.

Implementing Agency Assessment

78.

TERM-IU. This is a newly restructured entity, but with resources, experienced leadership

and high level GOT support to quickly access implementation support from across GOT, e.g.

from ministries responsible for environment and land/compensation issues. Procurement

training will be provided to designated technical staff and if necessary the proposed project will

support a short-term consultant to progress procurement activities initially. Financial

Management will be handled through the normal Ministry of Finance channels.

79.

Tonga Power Ltd. TPL is already implementing a new solar PV electricity supply on the

Tongatapu grid planned for August 2012 and preparing for subsequent renewable energy (RE)

projects on the other three grids. Managing the existing grid to accommodate RE supply is

becoming part of their core business. The support under the proposed project is integral to

TPL’s ability to plan and improve the grids to make best use of new RE supply. TPL will assign