Demand

advertisement

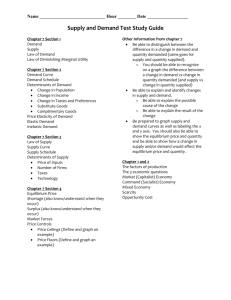

Demand, Supply and Price Determination Introduction In the usual and ordinary course of things, the demand for all commodities precedes their supply. David Ricardo (1772-1823) In grade 8 we introduced you to the economic problem. There it was explained that all economic actions arise from scarcity and that our wants exceed the productive resources at our disposal to satisfy these wants. In order to solve this basic economic problem, important decisions about what to produce, how to produce and for whom to produce have to be taken. In a market economy these decisions are mainly resolved by market forces which lead to price formation. These prices reflect the terms under which buyers and sellers are willing to exchange goods and services. The success or failure of any market economy therefore depends on how efficiently these price signals are conveyed to producers and consumers of products. The purpose of this study unit is to explain how prices are established in a market economy, through the interaction of demand and supply. Demand Let us begin our study of demand and supply by building a model of demand. You must make a clear distinction between the demand for a good or service and wants. wants are unlimited desires or wishes that people have for goods and services. the quantity of a certain good that people demand is the amount they actually plan to buy during a certain period of time. Therefore the amount we demand reflects a decision on which wants are going to be satisfied. Unlike wants, the demand for a good or service has to be backed up by buying power. Without buying power (income) there can be no demand. 1 What determines the amount demanded? Each one of us is a consumer of goods and services. Each day we require certain goods and services in order to stay alive. The amount of any particular good we plan to buy depends on many diverse factors. Let us list a few of these factors from our own experience: the price of the good the prices of other goods the income at our disposal our preferences weather conditions many more The price of a particular good or service is probably the most important factor mentioned above. Although all the other factors like income and the prices of related goods play a very important role in the demand for a specific product they can never be as important as the price of the good itself. In the light of this, we have to ask what is the relationship between the price and the quantity demanded of a good? The answer to this important question is provided by the law of demand. The law of demand states that: the higher the price of a good or service, the smaller the quantity demanded or the lower the price of a good or service the greater the quantity demanded. Obviously this law will apply only if all the other factors we have listed (income, preferences, weather etc.) remain unchanged. It is not possible to study the effect of a price change on the quantity demanded if these other factors are changing at the same time. Thus, the law of demand states that there is a definite relationship between the market price of a product (e.g. maize) and the quantity demanded of that product, all other things remaining the same. This relationship between price and the quantity demanded is called the demand schedule and we can represent the relationship graphically by means of a demand curve. In table 1 we give a hypothetical example of a demand schedule for maize. At any price, there is a definite quantity of maize which will be bought by all the consumers in the market. For instance, table 1 shows that at R5 a bag, consumers will buy 9 000 bags per month. At a lower price, say R4 per bag, the quantity which consumers will buy increases to 10 000 bags. From table 1 we can determine the quantity demanded at any particular price by comparing column 2 to column 1. (Remember, the figures are hypothetical; they are not actual prices or quantities.) 2 Table 1: Demand Schedule (shows the relationship between price and quantity demanded) A B C D E Price (P) (Rand per bag) Column 1 5 4 3 2 1 Quantity demanded (Q) (Bags per month) Column 2 9 000 10 000 12 000 15 000 20 000 The demand curve We can also represent the information given in table 1 graphically. In figure 1, the vertical axis shows the different prices of maize, measured in Rands per bag. The horizontal axis shows the quantities of maize (in terms of number of bags) demanded per month. We have used the information in table 1 to draw figure 1. Point A in figure 1 corresponds to a price (P) of R5 and a quantity of 9 000 bags of maize. You can read these figures off from the vertical and horizontal axes respectively. For point B, we take the next price (R4) and the corresponding quantity (10 000) from table 1, and we mark the point on our diagram which corresponds with these two figures. We obtain points C, D and E in the same manner. By connecting these points we obtain a line, shown as “dd”. Figure 1: The Demand Curve We call this the demand curve. We can draw a demand curve for any demand schedule. Note that Q (quantity) decreases when P (price) increases: we call this type of relationship an inverse relationship. An important property of the demand curve is that it slopes downward from left to right, which reflects this inverse relationship. This representation illustrates the law of demand which in fact applies to all goods - maize, meat, pizzas, hamburgers and also services such as those of hairstylists, medical practitioners and architects. 3 Reasons for the law of demand Our common sense tells us that this law is valid, and people have known it since early times, even if their knowledge of it was vague and intuitive. The substitution effect It is important to realise that when the price of a good rises, other things remaining the same, its price, relative to all other prices, rises. Because there are substitutes for most goods (e.g. coffee for tea) consumers will try to buy less of the product and more of its substitutes. The income effect When a price increases, the consumer is in reality in a poorer situation than he or she was before, because now the same amount of money buys less of that product than before. If income remains unchanged, any increase in the price of a product will make consumers poorer. They will thus be forced to reduce the quantities demanded of at least some goods and services. In all probability consumers will reduce their demand for the product whose price has increased. Both the substitution and the income effects substantiate the law of demand. Supply Let us now turn our attention from demand to supply. The demand schedule shows the relationship between prices and the quantities consumers wish to buy. What does the supply schedule show? The supply schedule (or supply curve) shows the relationship between the market price of a product and the quantity of that product that producers are willing to supply on the market. Table 2: Supply schedule (shows relationship between price and quantity supplied) A B C D E Price (P) (Rand per bag) 5 4 3 2 1 Quantity supplied (Q) (Bags per month) 18 000 16 000 12 000 7 000 0 Table 2 is, once again, a set of hypothetical figures for maize. This time, the quantities are the amounts supplied by sellers at each price. This information is also represented in figure 2 as a supply curve “ss”. In contrast with the demand curve, the supply curve rises from left to right. From the supply schedule in table 2 and the resultant supply curve in figure 2 we can derive the law of supply: 4 Figure 2: The Supply Curve Figure 2 clearly shows that more bags of maize will only be offered at higher prices. If the price drops to R1 per bag no maize will be produced. This is presumably because the production cost per bag is more than R1. The law of supply states that the higher the price of a good the greater the quantity supplied or the lower the price the smaller the quantity supplied (all other things remaining the same) As was the case with demand we again only look at the relationship between the price of the product and the quantity supplied. Clearly the amount producers plan to sell on the market will depend on a variety of factors such as: the price of the product the price (or cost) of factors of production the price of other products other suppliers of the product technology weather conditions Apart from the first factor (i.e. the price of the product) all the other factors are basically concerned with cost factors. Their influence on the quantity supplied stems from their influence on the cost of production. 5 Price determination There are two fools in every market; one asks too little, one asks too much Russian proverb We now know what demand and supply curves look like, but when examining figures 1 or 2 we still do not know precisely at which price the maize will be traded on the market. To answer this question we have to combine our analysis of demand and supply to see how price is determined in a free market situation. The combining of demand and supply is an important principle. So far we have considered all prices to be possible, and we have considered the effects of demand and supply separately. What we have really said is: "If the price is such and such, the amount consumers will buy is so and so", and "If the price is such and such, the amount producers will sell will be so and so". But how high (or how low) can prices actually go? How much will then be produced and consumed? Table 3 shows us that when we combine the market forces of demand and supply, the two will come into equilibrium (balance) at a certain price. We call this price the equilibrium market price. Table 3: The market equilibrium schedule Price Quantity demanded Quantity supplied Excess dd/Excess ss (Rand per bag) (bags per month) (bags per month) Pressure on price Column 1 Column 2 Column 3 Column 4 A 5 9 000 18 000 Excess ss - Decrease B 4 10 000 16 000 Excess ss - Decrease C 3 12 000 12 000 Neutral D 2 15 000 7 000 Excess dd - Increase E 1 20000 0 Excess dd - Increase Let us look at situation A in table 3, where maize sells at a price of R5 per bag. Is it possible that this situation can last for very long? At R5, the producers supply 18 000 bags on the market each month, as can be seen from column 3. But at that price, the quantity demanded by consumers is only 9 000 bags per month, as shown in column 2. Obviously, the answer is that the situation cannot last. Each month, 9 000 bags of maize will remain unsold. As the stock of maize increases, some suppliers will drop their prices a little to try and sell some of their stock. In other words, suppliers will start competing with one another in order to sell more maize. Thus, as column 4 shows, the price will tend to decrease - but it will not fall to zero. Let us now look at point E, where the price is only R1 per bag of maize. Can this price persist? Once again, the answer is no. A comparison of columns 2 and 3 shows us that at that price demand will exceed production. The shops will sell their maize and there will still be customers who want to buy. Disappointed customers will offer to pay more to make sure they get some maize. In other words, consumers will compete with one another in order to satisfy their wants. This upward pressure on prices is shown in column 4. We could go on and analyse other prices, but by now the answer should be obvious. 6 The only price which can persist is the price at which the quantity voluntarily supplied and the quantity voluntarily demanded are equal. We call this the equilibrium price. Competitive equilibrium price must be at the point where the demand and supply curves are the same. Only at point C, at a price of R3, will the quantity demanded by the consumers (12 000 bags per month), be exactly equal to the quantity supplied by the producers (12 000 bags per month). Here the price is at equilibrium, just as a marble at the bottom of a wine glass is at equilibrium - there a no tendency to fall or rise. In practice, this equilibrium price is not reached immediately and prices fluctuate around the right level until equilibrium is finally reached and the quantity demanded is equal to the quantity supplied. We can represent table 3 graphically, as shown in figure 3, where the demand and supply curves are combined in one diagram. Figure 3: Market equilibrium Figure 3 shows the equilibrium situation. The demand and supply curves, which both appear in the diagram, intersect one another at only one point. This point represents the equilibrium price and quantity. The diagram shows that at a higher price supply exceeds demand. The arrows point downwards to show the direction in which price will move because of competition between sellers. At a price lower than equilibrium price of R3 the demand is greater than supply, as shown in the diagram. The eagerness of buyers to buy the product will put upward pressure on the price, as arrows show. Only at the equilibrium point were upward and downward forces be in balance. 7 Activity (1) The demand and supply schedules for wheat are as follows: Price Quantity demanded Quantity supplied (Rand per bag) (Bags per month) (Bags per month) 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 a) b) c) d) 200 180 160 140 120 100 80 60 40 0 30 60 90 120 140 160 180 200 What is the excess supply when the price of wheat is R80 per bag? Will there be excess demand for wheat at a price of R20 per bag? What is the equilibrium price of a bag of wheat? What will be the quantity sold at this equilibrium price? (2) Draw the demand and supply curves of the schedules provided for wheat in question 1. (3) Indicate whether the following statements are true or false a) b) c) d) e) f) g) h) Wants and demand are the same. The most important factor influencing the demand for product A is the price of A. Income also influences the demand for consumer goods. The law of demand only applies when the prices of other products remain unchanged. The demand curve is derived from the demand schedule. The supply curve has an upward slope from left to right. Prices can be determined only if the demand and the supply of products are known. Equilibrium implies that market forces are in harmony with each other. 8