Presentation

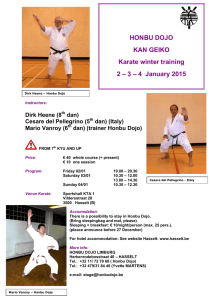

advertisement

Education as Dojo: Application of Aikido into Forming a Vision of a Just World Dianne R. Costanzo, Ph.D., Sensei “When the student is ready, the teacher will appear.” Zen Saying Like Most Zen sayings, this one teases us out of our usual way of perceiving things, providing us with a fresh way of seeing the world. To that end, I try to teach my classes in a slanted kind of way, creating a slight disturbance so that students cannot rely on the easy answer to get by. At Dominican University, I have had the extraordinary opportunity to offer a senior seminar called “Aikido as Contemplation.” It is an odd little class, which has been quite successful because it joins two apparently different worlds— academe and martial arts—and literally puts Aristotle’s idea of happiness in action. As someone who lives in these two worlds, I have come to believe that there is a nexus between thinking about the good and actually learning a martial art that emphasizes a harmonious engagement within inevitable conflict. By our practice, we learn how to choose our responses to the things that come into our lives, and by choosing harmony over harm, we cut a path within ourselves, so that ultimately what we do articulates who we are. 1 Students of this seminar spend one day a week in a traditional classroom where we discuss, among other texts, Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics. The other day students come to my dojo (school) to learn the basics of Aikido, a Japanese martial art that stresses leverage, timing, and body movement to neutralize another person’s attack without inflicting injury. While at the dojo, students become immersed in the culture of the dojo and the art of Aikido. It is a countercultural experience that calls students to act more intentionally and to begin to realize that the place of their learning provides a mirror in which to see themselves. One of the benefits of being in the dojo is that it makes students understand at a very deep level that the place itself is a kind of education. While many translate dojo as “school,” the literal meaning of the word is “place of enlightenment.” This realization of what dojo actually signifies demands students’ active participation in their own learning. From the time they enter the dojo, they are expected to take their shoes off and place them neatly near the door before bowing onto the mat. Once on the mat, students sit in a straight line and the teacher appears, sitting in front of them. Everyone bows to the shomen or front of the dojo where a picture of O Sensei, the founder of Aikido, is placed. This signifies that we honor all the teachers who have gone before us. The teacher then turns around, faces the students who bow, in this case, to me. The wonderful thing is that as they bow to me, I bow to them, recognizing one of the deepest truths of our practice: without a teacher, there is no student, but without the student, there is no teacher. Hence, even before students begin to learn any of the stretching or the techniques themselves, they have been given a model of behavior rooted in respect. 2 In fact, we bow all the time—when we enter the dojo, when we come on or off the mat, when we begin class, when students pair up to work with each other—lots of bowing. It is a simple yet profound act, which can take a lifetime actually to do with fullness and integrity. O Sensei once said, “When you bow to the universe, it bows back; when you call out the name of God, it echoes inside you” (The Art of Peace 123). It is all about the relationship people establish—within themselves, with another, with the place of their learning—sounds very Dominican, as we Dominicans believe that relationship is at the heart of ministry. The dojo itself is the place where aikidoka (Aikido students) practice their own self-realization, which is the entire point of Aikido. Because Aikido is non-competitive, those of us who practice believe that as we improve, we help others improve, and as others improve, they help us improve, creating a reciprocity within our training. Since the goal of our training is our own self-realization, the dojo is the furnace where ego softens up; the sensei is the one who stokes the fire, and the aikidoka are the iron that gets forged into steel. O Sensei said, “Iron is full of impurities that weaken it; through forging, it becomes steel and is transformed into a razorsharp sword. Human beings develop in the same fashion” (The Art of Peace 56). In the dojo, we are constantly throwing ourselves into what T.S. Eliot calls in Four Quartets “the refining fire.” Our training is not always pleasant, not usually easy, but always significant. Most people wish to improve, although not everyone wishes to do what is necessary to improve. Improvement requires effort and a profound willingness to give oneself to the practice. This exceeds simply mimicking what the teacher has demonstrated. To go back to the discussion on bowing, improvement begins as soon as one enters the dojo. 3 If the dojo is indeed the place of our enlightenment, it is an outer representation of what occurs internally; it is the place where we train the body and the soul. As O Sensei says, “From ancient times, deep learning and valor have been the two pillars of the Path: through the virtue of training, enlighten both body and soul” (The Art of Peace 57). I believe Aristotle would agree as he defines happiness as “an activity of soulfulness in accord with virtue” (Nicomachean Ethics 17). Cultivating virtue (hence happiness) is an activity, not a feeling. We learn our virtue by what we do and ultimately what we do articulates what we believe and shows who we are. If I want my students to make choices that are “good,” then they need to practice participating in the good. If they are to leave our Dominican colleges and universities on fire to create a more just and humane world, then they need to know how to choose the good. Their practice at the dojo can help them make their way as they physically learn not just a martial art, but the art of peace, a way of life: “The Art of Peace begins with you. Work on yourself and your appointed task in the Art of Peace. Everyone has a spirit that can be refined, a body that can be trained in some manner, a suitable path to follow. You are here for no other purpose than to realize your inner divinity and manifest your innate enlightenment. Forster peace in your own life and then apply the Art to all that you encounter.” (The Art of Peace 13) What they learn in the dojo is that Aikido is “the way of harmony through energy.” While certainly most students who take this seminar will not choose to study Aikido full time, they have nevertheless been introduced to a different 4 way of interacting with the world. They get a taste of what it means to be a warrior. We need warriors desperately—warriors, not fighters. To cite O Sensei once again, “Foster and polish the warrior spirit while serving in the world; Illuminate the Path according to your inner light (The Art of Peace 46). O Sensei himself stands as a wonderful example of what it means to give to his gift to the world as an offering of peace. Trained in many martial arts, Morihei Ueshiba (1883-1969), came to see war, competition, and the unjust power of the few over the many as defective and sinful. In 1942, he had the third of his visions into a deeper reality: “The Way of the Warrior has been misunderstood as a means to kill and destroy others. Those who seek competition are making a grave mistake. To smash, injure, or destroy is the worst sin a human being can commit. The real Way of a Warrior is to prevent slaughter—it is The Art of Peace, the power of love” (The Art of Peace 8). He called for a paradigmatic shift in understanding what the martial arts was for, and after the atrocities of World War II, O Sensei said that we must learn to wage peace. O Sensei’s understanding certainly underwent its own transformation. Originally called Aikijiutsu or harmonizing technique, the art of peace ultimately became Aikido, the way of harmony through energy. While one might argue semantics, it is imperative to note that O Sensei plunged more deeply into the essence of what he offered. He did not teach simply technique, but a way of life. In fact, he would dismiss students from his dojo if he felt that they did not possess the requisite character or virtue to study. 5 As Aikido grew in popularity, O Sensei was invited to teach in different dojo. O Sensei stepped into a dojo to teach as a guest instructor. Sensing that there was no proper spirit in that particular dojo, he walked out. Such is the power of place, if we actually can agree that a dojo or school holds the energy of those in it. If we can agree with that premise, then that creates a number of implications for us as teachers. One might infer that learning is more than transmitting information. While this is certainly important, it is the lowest level of learning—there is so much more. Learning has to be a formative event. It simply is insufficient that learning gets flattened out to trading factoids. Learning must be an active engagement between students and teachers, a kind of conversion process that can really turn iron into steel or, as the alchemists believed, lead into gold. Such an alchemical process cannot be perverted into specious snake oil sales people who trade on the insecurities, fears, and desires of the disenfranchised. Real alchemy does exist; we see it every day when we come into a class and a student “gets it.” That moment is sheer joy and cannot be necessarily predicted or manufactured, but it is made, crafted, created in the space or dojo that holds the student, the teacher, and the learning itself. Such deep learning takes time—not the tick tock time of the clock or even the semester, but time itself, a sinking into the learning, a sort of marinating and softening so that the learning can actually penetrate to the marrow. Ultimately, those of us who keep coming to the dojo and willingly place ourselves in the furnace to be purified and transformed get better, often in nearly imperceptible ways. But the learning is good, true, and beautiful; it becomes the gift we can 6 give to the world, whatever that gift may be. And by continuing to come to the dojo, we in fact create a dojo within ourselves. We call it education, a leading out of ignorance and an entrance into the world. As we go in, we also go out and find that both journeys are really the same. 7 8