TAP 32 Politics of Boom and Bust

advertisement

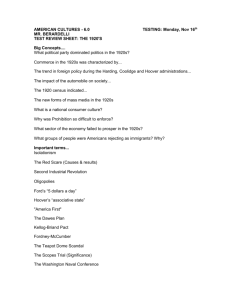

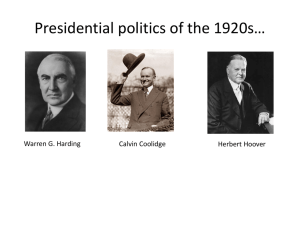

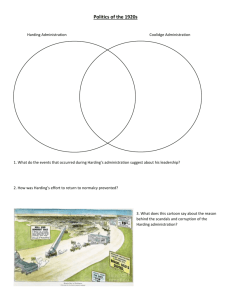

TAP Chapter 32: Politics of Boom and Bust Essential Questions: Why was the Republican platform attractive to Americans following World War I? How did economic policies of the 1920s set the stage for the crash and depression that followed? Harding’s Administration: Republican Conservatism Returns William G. Harding’s election in 1920 was a powerful referendum from the American people. Harding, an extremely popular but notoriously weak leader, used business, rather than government, to support the public good. His policies, then, represented an essential erasure of the progressive reforms of the Roosevelt, Taft, and Wilson administrations. As a president, Harding pushed for laissez-faire economic policies, and although he was in office for not even three full years, he made four Supreme Court appointments—staunch conservatives who favored business and wiped out the progressive legislation (namely anti-trust laws) of the preceding administrations. Reversing the nationalization of industry during World War I, Harding ended the War Industries Board and the nationalization of the railroads (a war-time measure implemented by Wilson). He immediately passed a high tariff (the Fordney-McCumber Tariff Law of 1922) in an effort to protect American industry, but caused international economic tensions. Furthermore, Harding’s administration sought to support fervently the veterans of World War I. Under his leadership, Congress created the Veteran’s Bureau and the American Legion. Other notable reversals of progressive legislation included: - Esch-Cummins Transportation Act of 1920 – returned the railroad industry to private hands after the war - Merchant Marine Act – regulated maritime commerce - Reversal of pro-union legislation Foreign policy of the 1920s represented a stark departure from the progressive era. Seeking to renew the resolve to remain unentangled from European conflicts, Harding reinstated an isolationist policy with regard to foreign affairs. The nation never even formally signed the Treaty of Versailles (instead, Congress signed a bill officially ending the war). Harding’s one foray into foreign affairs was his focus on disarmament, and he led the effort to sign the Nine-Power Treaty of 1922, which brought about disarmament measures in addition to affirming the Open Door policy with regard to China. The Kellog-Briand Pact, which followed in 1928 and was signed by the major powers involved in World War I, renounced aggressive war and affirmed American avoidance of European conflict. Yet, the loose morality and focus on get-rich-quick schemes in Harding’s administration led to scandal, the most famous of which was the Teapot Dome scandal in 1921, which led the American public to compare Harding to Ulysses S. Grant. “Silent Cal” Coolidge’s Administration Harding died suddenly during a trip to Alaska in 1923. President Harding’s death was a surprise to his vice president, Calvin Coolidge, who was sworn in to office by his father, a justice of the peace, in a cabin in New England during a family visit. As a president, Coolidge was ultimately a friend of business who once likened the factory to a temple of worship. He was personally thrifty, and such qualities led him to lower taxes, lower national debt, and usher in a period of prosperity for the American people. “The business of America is Business.” – President Calvin Coolidge Farmers did not profit from this prosperity in the 1920s, and as a result, they pushed aggressively for the McNary-Haugen Bill, which would have created government subsidies for crops. The bill was ultimately vetoed by Coolidge, who supported modernization of farming instead. Coolidge rode his popularity into a second term in the election of 1924. “Hoo but Hoover?” and the Crash of 1929 When Coolidge decided not to run for office in 1928, Republicans nominated Herbert Hoover of California, who ran against the Catholic Democrat Al Smith. Because Republicans were associated with the booming economy of the Roaring Twenties, Hoover, seen as the candidate of big business, won by a landslide in 1928. Hoover presided over about a year of profound prosperity, but was utterly surprised and devastated—along with the American people—when the Roaring Twenties crashed to a standstill in 1929. On October 29, 1929, the stock market, which had suffered a tumultuous four days, reached unthinkable lows. American fortunes collapsed overnight, tales of suicides abounded, and “regular” Americans plunged into poverty. Over the next few years, unemployment reached 18 percent and almost 10,000 banks failed, liquidating the savings inside. Historians have debated the causes of the crash and ensuing depression. Potential causes include: - Overproduction by farms and factories during the 1920s – the “plague of plenty” - Overexpansion of credit and installment-plan buying - A housing bubble that led to foreclosures throughout the country - Economic stagnation abroad, worsened by the Smoot-Hawley Tariff - Drought and dust bowl that worsened economic conditions Whatever the cause, Hoover’s response was seen as “too little, too late.” Certainly, the HawleySmoot Tariff, passed in 1930, which drove tariffs higher than ever before and essentially froze global commerce, did not help the American economy. While the American public was crying out for help, Hoover looked to businesses and individuals to practice volunteerism, rather than create public programs to relieve the people. As a result, Hoover bore a great deal of the blame for the depression, manifested by the “Hoovervilles” (shantytowns filled with Americans who had lost their homes) and “Hoover flags” (empty pockets) that were rampant during the late 1920s and early 1930s. He also dealt with an angry “Bonus Army” of veterans of World War I that descended on Washington in protest and to demand relief. Hoover finally did respond with the legislation below, but his “too little, too late” approach was considered inadequate, and the American public voted for sweeping change in the election of 1932. Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC) – gave loans to banks, railroads, and trusts to try to stimulate the economy Norris-La Guardia Anti-Injunction Act – banned courts from issuing injunctions against non-violent labor disputes Federal Home Loan Act – created banks to provide money to homeowners that needed loans National Credit Corporation – required the largest banks int eh country to give banks on the brink of foreclosure money to be used for loans Emergency Committee for Employment – tried to coordinate efforts between agencies to provide employment during early years of the Depression Hoover Dam – a project Hoover created to try to create jobs and provide flood control, electricity, and irrigation