The origin of concepts and the nature of knowledge revision boo

advertisement

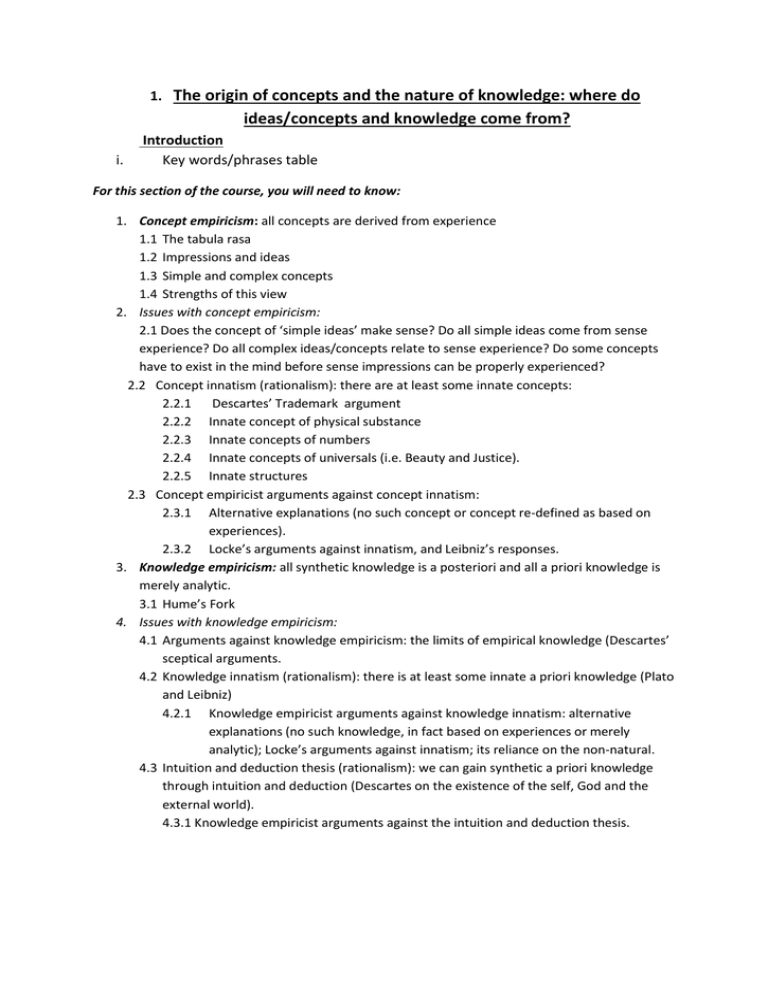

1. The origin of concepts and the nature of knowledge: where do ideas/concepts and knowledge come from? i. Introduction Key words/phrases table For this section of the course, you will need to know: 1. Concept empiricism: all concepts are derived from experience 1.1 The tabula rasa 1.2 Impressions and ideas 1.3 Simple and complex concepts 1.4 Strengths of this view 2. Issues with concept empiricism: 2.1 Does the concept of ‘simple ideas’ make sense? Do all simple ideas come from sense experience? Do all complex ideas/concepts relate to sense experience? Do some concepts have to exist in the mind before sense impressions can be properly experienced? 2.2 Concept innatism (rationalism): there are at least some innate concepts: 2.2.1 Descartes’ Trademark argument 2.2.2 Innate concept of physical substance 2.2.3 Innate concepts of numbers 2.2.4 Innate concepts of universals (i.e. Beauty and Justice). 2.2.5 Innate structures 2.3 Concept empiricist arguments against concept innatism: 2.3.1 Alternative explanations (no such concept or concept re-defined as based on experiences). 2.3.2 Locke’s arguments against innatism, and Leibniz’s responses. 3. Knowledge empiricism: all synthetic knowledge is a posteriori and all a priori knowledge is merely analytic. 3.1 Hume’s Fork 4. Issues with knowledge empiricism: 4.1 Arguments against knowledge empiricism: the limits of empirical knowledge (Descartes’ sceptical arguments. 4.2 Knowledge innatism (rationalism): there is at least some innate a priori knowledge (Plato and Leibniz) 4.2.1 Knowledge empiricist arguments against knowledge innatism: alternative explanations (no such knowledge, in fact based on experiences or merely analytic); Locke’s arguments against innatism; its reliance on the non-natural. 4.3 Intuition and deduction thesis (rationalism): we can gain synthetic a priori knowledge through intuition and deduction (Descartes on the existence of the self, God and the external world). 4.3.1 Knowledge empiricist arguments against the intuition and deduction thesis. Key words and phrases Ideas Ideas = concepts. Having a concept of something = being able to recognise it, think about it and distinguish it from other things. Simple Ideas Ideas that cannot be broken down into parts – e.g. ‘white’ and ‘cold’. Complex ideas Ideas that can be broken down into parts – e.g. ‘golden mountain’ and ‘unicorn’. Impressions Experiences/sensations, like the experience of seeing snow, or the sensation of pain. Outward impressions Experiences of the world outside us – e.g. from sight, hearing, touch, taste and smell. Inward impressions Experiences of things going on inside us – e.g. the experiences of pain, pleasure, happiness, sadness and anger. Propositions Sentences that make a claim about the way the world is – e.g. ‘There is a cat on the mat’ or ‘I am thinking about a dragon’. Analytic proposition Propositions that are true by definition – i.e. true just in virtue of the meaning of the words within them. E.g. ‘All bachelors are unmarried men’. Synthetic propositions Propositions that are not true by definition, but true or false depending on the way the world is. E.g. ‘all men are mortal.’ Necessary truths A truth that cannot be denied without contradiction. Examples: 2+2=4; triangles have three sides; all bachelors are unmarried men. Contingent truths A truth that can be denied without contraditiction. Examples: the sky is blue; grass is green; Winston Churchill was Prime Minister. Arguments An argument is a series of propositions intended to support a conclusion. The propositions offered in support of the concusion are called reasons or premises. Deductive arguments Arguments where the truth of the conclusion is guaranteed by the truths of the premises. For example: All men are mortal; Socrates is a man; so Socrates is mortal. Inductive arguments Arguments where the truth of the conclusion is not fully guaranteed by the truth of the premises. For example: The sun has always risen in the past, so the sun will continue to rise in the future. A priori knowledge Propositional knowledge that is acquired independently of experience (prior to it). Examples: the knowledge that 2+2=4 or that all bachelors are unmarried. A posteriori knowledge Propositional knowledge that is acquired from experience (after it). Examples: the knowledge that snow is white, or that the Atlantic is smaller than the Pacific. Innate knowledge Propositional knowledge that exists in the mind at birth, and so is not acquired by experience. Empiricism The philosophical position that all of our ideas, concepts, beliefs and knowledge are acquired from experience. Concept empiricism All concepts are derived from experience. There are no innate conepts. Knowledge empiricism The theory that there can be no a priori knowledge of synthetic propositions about the world (outside of my mind), i.e. all a priori knowledge is of analytic propositions, while all knowledge of synthetic propositions must be checked against sense experience. Rationalism The philosophical position that reason, rather than experience, is the most important source of ideas and knowledge. 1. Concept empiricism: all concepts are derived from experience 1.1 The tabula rasa: According to the empiricist John Locke, the mind is a ‘tabula rasa’ – a blank slate. Therefore all ideas/concepts are derived from experience – from impressions. There are two types of impressions: - Impressions of sensation: our experience of objects outside the mind, perceived through the senses. This gives us ideas of ‘sensible qualities’. - Impressions of reflection: our experience of ‘internal operations of our minds’, gained through introspection or an awareness of what the mind is doing. Locke uses the term ‘idea’ to cover sensations and concepts! ‘Let us then suppose the mind to have no ideas in it, to be like white paper with nothing written on it. How then does it come to be written on? From where does it get that vast store which the busy and boundless imagination of man has painted on it – all the materials of reason and knowledge? To this I answer, in one word, from experience. Our understandings derive all the materials of thinking from observations that we make of external objects that can be perceived through the senses, and of the internal operations of our minds, which we perceive by looking in at ourselves.’ (Locke, An Essay Concerning Human Understanding, II, 1, par.2) 1.2 Impressions and ideas Hume develops John Locke’s empiricist philosophy. Hume argues that what we are immediately and directly aware of are ‘perceptions’. ‘Perceptions’ are divided into ‘impressions’ and ‘ideas’, the difference between the two being marked by a difference of ‘forcefulness’ and ‘vivacity’, so that impressions relate roughly to ‘feeling’ (or ‘sensing’) and ideas to ‘thinking’. Hume argues that ideas are faint copies of original sense impressions (Hume’s Copy Principle). For example, my ideas of whiteness and coldness are copies of my sensation of the whiteness and coldness of snow. Because this sensation was forceful and vivid, it stamped a copy of itself on my mind. This copy is considerably fainter than the original sensation. If I create other ideas from it, they will be fainter still. All of our ideas are built up from copies of our impressions, by combining, separating, augmenting and diminishing them. Hume, following Locke, divides impressions into those of ‘sensation’ and those of ‘reflection’. Impressions of sensation derive from our senses, impressions of reflection derive from our experiences of our mind, including emotions for Hume. Impressions = the more lively sensations that we have when we see or hear or feel or love or hate. Ideas = the less lively sensations that we have when we think about seeing, hearing, feeling etc. 1.3 Simple and complex concepts ‘But although our thought seems to be so free, when we look more carefully, we’ll find that it is really confined within very narrow limits, and that all this creative power of the mind amounts merely to the ability to combine, transpose, enlarge or shrink the materials that the senses and experiences provide us with.’ Hume, Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding, Enquiry 1, section 2. Both Locke and Hume distinguish between simple and complex ideas. They argue that ideas which do not come directly from experience (e.g. the idea of a unicorn) are all built out of simpler ideas that do come from experience (the ideas of a horse and a horn). For example, I see a mountain and something golden, and combine the ideas generated by these impressions to form the idea of a golden mountain (Hume’s example). 1.4 Strengths of this view It fits with our experience of the acquisition of ideas – we acquire ideas of things as we experience them, and not before (Locke). It explains why people who lack certain kinds of sensation also lack the corresponding ideas – e.g. why blind people have no ideas of colours, and deaf people no idea of sounds (Hume). It gives us a way of resolving philosophical problems – clarify the ideas on which they are based and the problems will disappear. Hume applies this to philosophical problems about causation, God, morality and the self. Hume’s two arguments for concept empiricism: 1) When we analyse our thoughts or ideas—however complex or elevated they are—we always find them to be made up of simple ideas that were copied from earlier feelings or sensations. Even ideas that at first glance seem to be the furthest removed from that origin are found on closer examination to be derived from it. The idea of God—meaning an infinitely intelligent, wise, and good Being—comes from extending beyond all limits the qualities of goodness and wisdom that we find in our own minds. However far we push this enquiry, we shall find that every idea that we examine is copied from a similar impression. 2) If a man can’t have some kind of sensation because there is something wrong with his eyes, ears etc., he will never be found to have corresponding ideas. A blind man can’t form a notion of colours, or a deaf man a notion of sounds. Hume, An Enquiry Concerning Human understanding, Section 2, p.8 2. Issues with concept empiricism: 2.1 Does the concept of ‘simple ideas’ make sense? Do all simple ideas come from sense experience? Do all complex ideas/concepts relate to sense experience? Do some concepts have to exist in the mind before sense impressions can be properly experienced? (a) Does the concept of ‘simple ideas’ make sense? Simple concepts can be analysed further. For example the simple concept of a mountain can be further analysed into the concept of rock, the concept of snow, the concept of grass, etc. Although these collections of ideas do not necessarily add up to the complete concept of ‘mountain’. The question is, when does the analysis stop? When do we find a simple impression? This demonstrates a difficulty for the empiricist in working out the details of their theory of impressions and ideas. (b) Do all simple ideas come from sense experience? Hume’s missing shade of blue: if it is possible to form an idea without a corresponding impression (the idea of the missing shade of blue without the impression of this shade of blue) this goes against the principle that nothing can exist in the mind that has not come through the senses , undermining the most basic tenet of empiricism. ‘Can he fill the blank [shade] from his own imagination, calling up in his mind the idea of that particular shade, even though it has never been conveyed to him by the senses? Most people, I think, will agree that he can. This seems to show that simple ideas are not always, in every instance, derived from corresponding impressions. Still, the example is so singular that it’s hardly worth noticing, and on its own it isn’t a good enough reason for us to alter our general maxim.’ Hume, An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding, Enquiry 1, Section 2, Hume does not seem to adequately respond to the problem he poses, arguing that this is simply an exception to the general rule. However, if we can form this concept without having had an impression, why should we not be able to form others? One response is to say that missing shade of blue is a complex concept and can be formed from the idea of ‘blue in general’ and the concepts of ‘dark’ and ‘light’. However, then all ideas of colour would be complex concepts – how would we form the simple concept? The empiricist could also respond that we cannot actually form the concept of the missing shade of blue, but the implications of this would be that we would have to experience millions of different shades of colours to form the concepts of each colour. (c) Do all complex ideas/concepts relate to sense experience? We can have concepts of things we have never experienced; for example I can form the concept of Italy having never been there and I can form the concept of an atom without being able to see it. How do we acquire concepts of abstract concepts such as freedom or justice? We don’t seem to have sense impressions of these concepts. Empiricists might respond that with abstract concepts there will be a complex route back to experience, i.e. we can form the concept of justice from observing justice acts. Do relational concepts (e.g. ‘being near’, ‘being far’, ‘on’, below’, ‘behind’ etc.) derive from impressions? I can have a sense impression of a cat and a mat but I don’t seem to have a sense impression of ‘on-ness’ so, according to the empiricist, how would one form the concept of the cat on the mat? (d) Do some concepts have to exist in the mind before sense impressions can be properly experienced? Our brains must have some concepts or structures already in place for our sense experiences to make sense. For example, Condillac’s statue would experience a flow of sense data without being able to categorise this sense data. The statue would experience what William James has called ‘a blooming, buzzing confusion.’ Immanuel Kant argued that there must be conceptual schemes in place for us to categorise and understand our sense experiences. 2.2 Concept innatism (rationalism): there are at least some innate concepts. Locke (who denied the existence of innate ideas) defines innate ideas as: ‘[S]ome primary notions... Characters as it were stamped upon the Mind of Man, which the Soul receives in its very first Being; and brings into the world with it.’ Locke, An Essay Concerning Human Understanding, 1, 2, par. 1 2.2.1 Descartes’ Trademark argument Descartes tried to prove the existence of God in his Trademark argument by arguing that we have an innate idea of God that has been ‘stamped’ on our mind by God. Descartes argues that humans have an idea of a perfect and infinite being (God). However, as humans are finite and imperfect, we cannot have created this idea ourselves. The idea must come from an infinite and perfect being – God – therefore proving God’s existence. ‘But these attributes [of God’s] are so great and eminent that the more attentively I consider them, the less I am persuaded that the idea I have of them can originate in me alone. And consequently I must necessarily conclude from all I have said hitherto, that God exists; for, although the idea of substance is in me, for the very reason that I am a substance, I would not, nevertheless, have the idea of an infinite substance, since I am a finite being, unless the idea has been put into me by some substance which was truly infinite.’ Descartes, Meditations, page 124. Hayward, Jones and Cardinal give Descartes’ Trademark argument in a formal style: - Premise 1: The cause of anything must be at least as perfect as its effect [The Causal Principle] - Premise 2: My ideas must be caused by something. - Premise 3: I am an imperfect being. - Premise 4: I have the idea of God, which is that of a perfect being. - Intermediate conclusion 1: I cannot be the cause of my idea of God. (From premises 1,2,3 and 4). - Intermediate conclusion 2: Only a perfect being (that is, God) can be the cause of my idea of God. (From premise 1 and 4 and IC1). - Main conclusion: God must exist. (From premise 4 and IC2). Hayward, Jones and Cardinal, AQA AS Philosophy, p.126). Problems with Descartes’ Trademark argument: - There are problems with Descartes’ Causal Principle (that ‘there must be at least as much reality in the efficient and total cause as in its effect’ Meditations) because there seem to be examples of effects have more perfection or reality than their causes. Examples: a match causing a bonfire; a whisper causing an avalanche; the natural process of evolution. So the idea of God needn’t come from God. - Humans don’t have the idea of infinity (the most humans can have is the idea of the opposite of finite). So, if humans don’t have an idea of an infinite being then Descartes’ argument fails. - The idea of God is incoherent (e.g. the paradox of the stone). So the idea of God is unclear and would not be caused by God but could have been caused by Descartes himself. - The idea of an all-powerful God is not universal and therefore this idea may have arisen at one point in history rather than being innate. - Empiricists can explain how we have the idea of God through abstracting qualities and characteristics we observe in the world. For example, we experience wise, kind and strong people and abstract out these characteristics infinitely to form the idea of an omniscient, omnibenevolent and omnipotent being, God. 2.2.2 Innate concept of physical substance Descartes argues that the concept of a physical object does not derive from sense experience, but is innate. He argues this through using the example of a block of wax. When cold, the wax sounds, feels, looks and smells a certain way, for example it is hard and makes a sound when struck with a finger. However, when the block of wax is melted, it changes shape and colour, it feels and smells differently and it no longer makes a sound when struck by a finger. Therefore, all the original sensory qualities of the wax have changed. However, Descartes argues that we would still believe that this is the same block of wax. As our senses cannot tell us that this is the same block of was – because all the sensory qualities of the wax have changed – it is our understanding that tells us that this is the same wax. Therefore, our idea of physical objects belongs in the understanding and thus is innate. 2.2.3. Innate concepts of numbers Both Plato and Descartes argued that our concepts of numbers are innate. Plato argues that we cannot have sensory experiences of numbers – for example, we can have sensory experiences of pairs of things but never the number 2 itself – so our concepts of numbers must be innate. Plato argues that we encounter numbers in the World of Forms – a realm of pure thought – before birth. Empiricists can reply that we form the concepts of numbers from abstracting out from sensory experiences of collections of objects in the world. However, Descartes argues that we can form the concept of a shape with one thousand sides without being able to form a clear image of this shape. So, we can form concepts (we can understand) numbers and shapes that we have never encountered. So, the concepts of numbers and shapes are not acquired through sensory experience but exist in the innately in the mind. 2.2.4. Innate concepts of universals (i.e. Beauty and Justice). Plato argues that our concepts of universals such as beauty and justice are innate and we encounter these universals in the world of forms before birth. He argues that we cannot acquire these concepts through sensory experience because we only ever observe particular examples of beautiful or just things, never Beauty or Justice itself. Additionally, in order to be able to recognise when particular things are beautiful or particular actions are just, we must first possess the concepts of beauty and justice. If we did not possess these concepts, we wouldn’t be able to recognise or learn about beautiful or just things. 2.2.5. Innate structures. Kant believed that humans possess innate concepts in their minds in order to structure, categorise and make sense of their sensory experiences. ‘Thoughts without content are empty; intuitions [impressions] without concepts are blind.’ (Kant, Critique of Pure Reason). Therefore, rather than the human mind passively receiving sensory information, the human mind is active in shaping sensory experiences of the world. Examples of innate concepts for Kant include: causation; time and space, and unity. Noam Chomsky has also argued that humans innately posses the capacity to learn language – just hearing and experiencing language would not be enough for humans to learn language. 2.3 Concept empiricist arguments against concept innatism: 2.3.1 Alternative explanations (no such concept or concept re-defined as based on experiences). 2.3.2 Empiricist arguments against an innate idea of God: - Our concept of God comes from us abstracting qualities we observe in the world. For example, we experience wise, kind and strong people and abstract out these characteristics infinitely to form the idea of an omniscient, omnibenevolent and omnipotent being, God. - Some Empiricists might also argue that not all humans have the concept of God. They might also argue that we do not have the concept of an infinite being – we only have a negative concept of infinite as the opposite of finite. Empiricist arguments against an innate idea of physical substance: - we can form the concept of extension through abstracting from our changeable sensory experiences. Empiricist arguments against innate ideas of numbers: - We acquire the concepts of numbers from abstracting out from our experiences of collections of objects. For example, by having experiences of pairs of things, we can recognise what they have in common and abstract out the concept ‘two’. Empiricist arguments against innate ideas of universals such as beauty and justice: - We have many experiences of beautiful objects (e.g. paintings, sunsets) and we recognise what each of these experiences has in common and abstract out the concept of ‘beauty’ from these experiences. Similarly with justice; we abstract out the concept of justice from recognising similarities in our experiences of just acts. Locke’s arguments against innatism and Leibniz’s responses. In Locke’s Essay Concerning Human Understanding, he sets out to show that innate ideas do not exist (that the mind is indeed a Tabula Rasa). Locke’s arguments against the existence of innate ideas are: (a) Innate ideas are not necessary: ‘... men can get all the knowledge they have, and can arrive at certainty about some things, purely by using their natural faculties, without help from any innate notions or principles.’ Locke, An Essay Concerning Human Understanding,1,2, par.1 - Locke argues that innate ideas are unnecessary because the acquisition of all concepts can be explained with reference to sensory experience. For example, Locke argues that it is clear that we experience colours through our sight and therefore, why would God or nature also give us an innate idea of colour if we can also acquire this concept through experience? - Therefore, if all ideas can be explained with reference to experience, why should we suppose that we have innate ideas? Using Occam’s razor, we should go for the simpler explanation – that all ideas are acquired from experience. ‘Everyone will agree, presumably, that it would be absurd to suppose that the ideas of colours are innate in a creature to whom God has given eyesight, which is a power to get those ideas through the eyes from external objects. It would be equally unreasonable to explain our knowledge of various truths in terms of innate ‘imprinting’ if it could just as easily be explained(b) through abilities to come to know things.’ Thereour areordinary no universal ideas, so there are no innate ideas: Locke, An Essay Concerning Human Understanding,1,2, par.1 ‘Nothing is more commonly taken for granted than that certain principles ... are accepted by all mankind. Some people have argued that because these principles are (they think) universally accepted, they must have been stamped onto the souls of men from the outset.’ Locke, An Essay Concerning Human Understanding,1,2, par.2 - Locke argues that there are no innate ideas because there are no ideas which are universally held (held by everyone). - To demonstrate this, Locke uses two examples from logic: the law of identity, ‘Whatever is, is’ and the law of non-contradiction, ‘it is impossible for the same thing to be and not to be’. He argues that while these are accepted as strong contenders for innate ideas, they are not universally held because ‘children and idiots’ do not possess these concepts. ‘Children and idiots have no thought – not an inkling – of these principles, and that fact alone is enough to destroy the universal assent that any truth that was genuinely innate would have.’ Locke, An Essay Concerning Human Understanding,1,2, par.5 - Leibniz responds to this criticism by saying that ‘children and idiots’ do possess these concepts; however they are unable to fully articulate these concepts in words. He argues that they show they possess these concepts due to the ways in which they act. Therefore, these concepts could be universal. - Leibniz also responds by arguing that innate ideas do not need to be universal: (i) He argues firstly that not all universal ideas are innate; even if the whole world smoked, this would not mean that the desire to smoke was innate. (ii)Secondly, not all innate ideas need to be universal as God could choose to give certain ideas to only some people. (c) The transparency of our minds: - Some Innatists argue that innate ideas exist in the mind but people are not always aware of them until later in life. -However, Locke argues that if the mind has certain ideas imprinted on it then the person would be aware of these ideas – the mind is transparent. - If we do not know we have an idea of something/we have never thought about it, then how can the idea be ‘in’ our minds? ‘To imprint anything on the mind without the mind’s perceiving it seems to me hardly intelligible. So if children and idiots have souls, minds, with those principles imprinted on them they can’t help perceiving them and assenting to them.’ Locke, An Essay Concerning Human Understanding,1,2, par.5 - Leibniz’s responds by arguing that we can acquire a concept without being conscious of doing so, for example ‘absorbing’ the tune of a song playing in the background without being aware of doing so. Therefore, if we can possess ideas subconsciously, then this undermines Locke’s argument that the mind is transparent. (d) It would not be possible to distinguish innate ideas from ideas acquired through experience. - If some Innatists claim that innate ideas exist but people may not become conscious of them until later in life then how can we distinguish between innate ideas and ideas gained through experience? - Leibniz replies by saying that we can distinguish between innate ideas and ideas acquired through experience because innate ideas are necessary, such as the truths of mathematics, geometry and logic. Because these types of truths are eternal, they cannot have been acquired from experience but only through reason. (e) Innatism relies on the supernatural. - Many Innatists claim that our innate ideas are imprinted on our minds before birth by God. - Locke argues that because empiricism can explain how we acquire ideas naturally, with no need for God/ the supernatural, it is a more plausible theory of the origin of our ideas. - However, some Innatists claim that we have innate ideas due to the way our brains have evolved, so innatism does not have to rely on the supernatural. 3. Knowledge empiricism All synthetic knowledge is a posteriori and all a priori knowledge is merely analytic. 3.1 Hume’s Fork ‘All the objects of human reason or enquiry fall naturally into two kinds, namely relations of ideas and matters of fact.’ (Hume, An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding, Enquiry 1, section 4.) - Hume divides all objects of enquiry into two types – relations of ideas and matters of fact. - Relations of ideas are analytic truths. As such, they are necessarily true, and can be known a priori (deductively) and with certainty. - Matters of fact are synthetic truths. As such, they are only contingently true, and can only be known a posteriori (inductively), without certainty. - So, Hume’s empiricism about knowledge is that: The only truths that we can know independently of experience are analytic truths (i.e. relations of ideas – trivial tautologies that tell us nothing about the world and what exists). All substantive (synthetic) truths about the world, and what exists in it, must be known by experience. So, all synthetic knowledge is a posteriori and all a priori knowledge is merely analytic. Strengths of Hume’s empiricism: - It is supported by the plausible scientific idea that we need to use observation and experiment to find out about the world outside of us. - It explains how we acquire some knowledge independently of experience, by saying that all such knowledge is about things which are internal to us (namely; ideas). - It explains why there always seem to be problems with a priori arguments for substantive truths about the world (e.g. the ontological argument, the trademark argument, Plato’s arguments for the Forms, arguments for the existence of the soul, etc.) 4. Issues with knowledge empiricism 4.1 Arguments against knowledge empiricism: the limits of empirical knowledge (Descartes’ sceptical arguments. As our synthetic knowledge is acquired solely a posteriori, through a process of induction and generalising from experiences (for example, the sun has risen in the past so the sun will rise in the future) it is not certain. Because this knowledge is not certain it can be challenged by scepticism. While we may be certain that we are having sensory impressions we cannot be certain in moving from these impressions to beliefs about the world. Descartes highlights the uncertainty of information gained through the senses in the sceptical argument he uses within his Meditations. Using his ‘three waves of doubt’ he attempts to doubt all of his beliefs in order to find a set of infallible beliefs from which to build a system of certain knowledge. ‘Some years ago I was struck by how many false things I had believed, and by how doubtful was the structure of beliefs that I had based on them. I realised that if I wanted to establish anything in the sciences that was stable and likely to last, I needed – just once in my life – to demolish everything completely and start again from the foundations.’ Descartes, Meditations on First Philosophy, Meditation 1. Descartes’ first wave of doubt (the argument from illusion) involves him doubting his senses because they have fooled him before. For example, he might believe he sees a friend walking on the other side of the road, only then to find out it wasn’t actually his friend. However, he realises that under normal conditions (for example up close and in normal lighting) he can trust his senses. His second wave of doubt (the argument from dreaming) involves him doubting his senses because he could be dreaming. He argues that while he is experiencing sitting in front of a fire writing a book, he has often dreamed about this, so how can he tell apart dreaming and waking reality? However, he recognises that the materials of his dreams must be formed from reality. Therefore, there must be a real external world from which the ideas in his dreams can be built. His third and final wave of doubt (the argument from the evil demon) involves him suggesting that there could be an evil demon deceiving him about everything. This demon might trick Descartes into believing there is an external world or of mathematical truths such as 2+2=4. (The matrix is a contemporary example of the evil demon problem – that we are deceived about the external world). ‘So I shall suppose that some malicious, powerful, cunning demon has done all he can to deceive me... I shall think that the sky, the air, the earth, shapes, and all external things are only merely dreams that the After usingcolours, the three wavessounds of doubt, Descartes finds that the belief that he can bedemon certainhas contrived as traps my judgement. I shall consider having no hands eyeshis or flesh, or blood or senses, but of for is that he – as a thinking being myself exists –asbecause even to or doubt existence involves as having falselythinking. believedDescartes that I had concludes, all these things.’ on FirstIPhilosophy, Meditation ‘CogitoDescartes, ergo sum’Meditations – ‘I think therefore am.’ It is from this belief1. that Descartes builds his system of knowledge. Thus Descartes critiques the empiricist ideology of knowing about the world through the senses. Additionally, if all knowledge of synthetic propositions can only be gained from sensory experience then it would follow that to know that God or morality existed you would have to have sensory experiences of God or morality and many argue that this is not possible. 4.2 Knowledge innatism (rationalism): there is at least some innate a priori knowledge (Plato and Leibniz) (a) Plato’s knowledge innatism: Plato believes that we have immortal souls which before birth encounter the world of forms – a realm of pure thought and perfect concepts in their pure state, for example ‘Beauty itself’, ‘Justice itself’ and truths of mathematics and geometry. When our souls are born into our bodies we forget most of these forms; however, through a process of reasoning to prompt our memories we can access this innate knowledge in our minds. Therefore, learning is a form of remembering. The famous example Plato gives to demonstrate this is the dialogue between Socrates and the slave boy in his Meno. Socrates asks the slave boy a series of questions on a geometrical theory. Through the discussion and the series of questions, Socrates draws out the answer from the slave boy. Plato argues that the boy innately possessed this knowledge but it needed to be drawn out through reason – Socrates’ questions triggered the knowledge the boy already possessed. For Plato, this knowledge of the geometrical theorem could not have been acquired through sense experience because as soon as we recognise the truth we realise that it has a universal application (it does not just apply to one square but all squares); however, through the senses we only ever experience particular examples of things. A criticism of Plato’s argument for innate ideas is that it rests on the metaphysical assumption that a realm of forms exists and that we experience it before birth. A further criticism of Plato’s argument for innate ideas is that, in his slave boy example, Socrates implicitly teaches the boy the geometrical theorem through his questioning and thus his knowledge his acquired a posteriori and is not innate. Locke’s criticisms of innate knowledge: (As Locke defines an idea as any ‘immediate object of perception, thought, or understanding’ also see section 2.3.2 on Locke’s criticisms of innate ideas). (i) If there was innate knowledge then it would be universal. However, there is no idea/piece of knowledge that is universally held. For example, ‘children and idiots’ do not know the law of identity or the law of non-contradiction. Therefore, if no idea/piece of knowledge is universal, no knowledge is innate. (ii) Locke argues that the most we can say is that the capacity for knowledge is innate. This means that we are born with the ability to know things; however, this is not the same as being born possessing innate knowledge. As Lacewing puts it, ‘the capacity to see (vision) is innate, but that doesn’t mean that what we see is innate as well!’ (Philosophy for AS, p.121). (iii) (iv) If we have to ‘discover’ innate knowledge through reasoning, then how can we know it is innate and not actually gained through experience? Not everyone agrees on moral principles, so morality cannot be innate because if it was, it would be self-evident to people. (b) Leibniz’s knowledge innatism (responding to Locke): Leibniz wrote his New Essays on Human Understanding as a response to Locke, arguing that we do indeed possess innate knowledge. Leibniz responds to Locke’s argument that there is no innate knowledge because there are no universally held ideas (for example children don’t know the law of identity and the law of non-contradiction) by arguing that children do possess this knowledge ‘without explicitly attending to it’. So, whilst children cannot articulate this knowledge in words, they still possess it and use this knowledge all of the time. Therefore, knowledge can be unconscious – critiquing Locke’s claim that our minds are fully aware of all the ideas we possess. Leibniz argues that all necessary truths are innate because experience is not able to give us the knowledge of necessary truths. Leibniz does argue that sense experience might be needed to trigger our innate knowledge; however, sense experience is not enough to give us necessary knowledge. For example, we might gain knowledge of God through experience and teaching but our knowledge of God as a necessary being goes further than this and therefore must be known innately. Leibniz responds to Locke’s claim that innate knowledge is only the capacity for knowledge by arguing that, while innate knowledge is not ‘fully formed’ it is more than just a capacity for knowledge. Innate knowledge exists as potential knowledge in our minds, needing to be fully formed. An analogy Leibniz gives for this is a block of marble; ‘the veins of the marble outline a shape that is in the marble before they are uncovered by the sculptor’ (New Essays on Human Understanding).So innate knowledge exists as potential knowledge and dispositions in the minds of humans that needs to be uncovered (through reason and experience). 4.2.1 Knowledge empiricist arguments against knowledge innatism: alternative explanations (no such knowledge, in fact based on experiences or merely analytic); Locke’s arguments against innatism; its reliance on the non-natural. Alternative explanations: - Empiricists argue that necessary truths such as 2+2=4 are a priori but analytic. They argue that we acquire the concept from experiencing, and then, in understanding the concept, we come to know necessary truths. Therefore these truths (or the potential knowledge of these truths) do not need to exist already in the mind. - While it is easier to show how the truths of logic and mathematics are analytic, it is more difficult for moral truths. However, Locke argues that moral truths are analytic and can be deduced from other analytic truths. On the other hand, Hume argues that there is no moral knowledge because moral claims are actually just expressions of emotions and feelings; they cannot be true or false because they are not propositions. Locke’s arguments against innatism (see above). Innate knowledge’s reliance on the non-natural: - Plato’s argument that the mind/soul exists before birth in the realm of the forms. - Leibniz’s theory depended on the existence of a God. - Descartes argued that our innate knowledge depends on it being planted there by God. - All three philosophers appeal to God and the supernatural to explain why they think we have innate knowledge. Innate knowledge therefore requires a more complicated explanation for its existence than knowledge acquired through experience, and thus could be objected to by using Occam’s razor. - However, some modern philosophers have argued that we possess this innate knowledge due to evolution and therefore there is no need to appeal to the supernatural. 4.3 Intuition and deduction thesis (rationalism): we can gain synthetic a priori knowledge through intuition and deduction (Descartes on the existence of the self, God and the external world). Empiricists claim that all knowledge of synthetic propositions is a posteriori, while all a priori knowledge is of analytic propositions. So, anything we know that is not true by definition or logic alone, we must learn and test through the senses. Rationalists deny this, claiming that there is some a priori knowledge of synthetic propositions. According to rationalists there are two key ways in which we gain such knowledge: (i) The knowledge is innate (already in our minds at birth). (This was discussed in section 4.2) (ii) Rational ‘intuition’ and deduction together help us to acquire certain truths intellectually. We will now be focussing on (ii). Rationalists argue that we can deduce synthetic knowledge about the world from our rational intuition a priori (without experiencing/observing the world). Rational intuition involves discovering the truth of a claim just by thinking about it. Descartes argued that we can establish knowledge of the existence of the self, God and physical objects through rational intuition and deduction. (a) Descartes on the existence of the self. - After using his three waves of doubt, Descartes concluded that ‘cogito ergo sum’ – ‘I think therefore I am’ – was the only piece of knowledge he could be certain of. He thought this because, even if he doubts his own existence, he is still thinking and thus he cannot doubt that a thinking thing exists: ‘he [the evil demon] will never bring it about that I am nothing while I think I am something.’ - From this truth, Descartes hope to build his system of infallible beliefs. Descartes, Meditations on First Philosophy, Meditation II. - At this point, Descartes does not know whether or not he has a body; he can only know that he is a thinking thing: ‘a thing that doubts, understands, affirms, denies, wants, refuses, and also imagines and senses’ Descartes, Meditations on First Philosophy, Meditation II. - Descartes knows what type of thought he is engaging in; for example ‘affirming’, ‘sensing’, ‘imagining’, etc. and he cannot be wrong about this – he can’t mistakenly think he is affirming when he is actually imagining. - Descartes defines his idea of the cogito (the existence of a thinking thing) as clear and distinct. - He then argues that, whatever he can perceive clearly and distinctly is true. - Descartes defines a clear idea as: ‘ present and accessible to the attentive mind – just as we say that we see something clearly when it is present to the eye’s gaze and stimulates it with a sufficient degree of strength and accessibility.’ - He defines a distinct idea as: ‘so sharply separated from all other ideas that every part of it is clear.’ - For Descartes, our rational intuition is knowing that clear and distinct ideas are true. - Therefore, Descartes has shown how, through a process of rational intuition and deduction, he can know the synthetic truth that the self exists. -However, Descartes questions that, while we must consider that a clear and distinct thought is true when we consider it, how do we know that it is true when we are not focussing on it? - In order to know whether clear and distinct thoughts are true when we are not focussing on them, Descartes argued that we need to know that we are not being deceived by God or an evil demon. - Therefore, Descartes sets out to prove that we are not being deceived in order to establish the truthfulness of clear and distinct ideas and, from that, the existence of an external world. (b) Descartes on the existence of God. - Descartes offers two a priori arguments to prove the existence of God: His Trademark Argument and his Ontological argument. - Both of these arguments move from an idea of an omnipotent and perfect being to the existence of this being. - In addition to proving God’s existence, Descartes needs to show that this God would not let us be deceived. - It is a clear and distinct idea that God’s perfection is not compatible with deception. - Therefore, God would not deceive us or let us be deceived by an evil demon. (c) Descartes on the existence of the external world. - Descartes argues that he has a clear and distinct idea of what a physical object is. - He also argues that his perceptions of physical objects are involuntary and ‘much more lively and vivid’ than imagination or memory. - As his perceptions are involuntary they cannot be caused by himself (otherwise he would know about the cause of them) so they must be caused by something external to him. - As God exists and is perfect and not a deceiver, Descartes’ perception of physical objects must be caused by physical objects themselves. - Therefore, there is an external world of physical objects causing our perceptual experiences. Therefore, according to Descartes, he is able to prove the existence of the self, God and an external world through a process of rational intuition and deduction rather than sensory experience. (d) Geometry Geometry is another proposed example of how we can gain substantive knowledge of the world independently of the senses. For example, the Greek mathematician Euclid started with a set of self-evident axioms and definitions (e.g. All right angles equal each other) and moved from these to prove a further set of propositions. Through the careful use of reason, Euclid was able to establish a large and systematic body of truths all derived from his initial axioms and definitions. It is argued that the truths established through reason are synthetic rather than merely analytic because they can be applied to the world (for example we are able to construct buildings and bridges using geometrical propositions). Geometry seems to be telling us new facts about the nature of physical space, facts that have genuine application and are not just true by definition. 4.3.1 Knowledge empiricist arguments against the intuition and deduction thesis: Mathematical and geometrical knowledge is a priori but analytic (rather than synthetic) according to the knowledge empiricist – in order to know mathematical truths we simply need to analyse the concepts involved. Additionally, if the mathematical/geometrical initial assumptions are derived from experience, then the whole system is grounded in experience anyway and we are not gaining any new knowledge a priori. Descartes has not managed to prove that he knows he is a thinking thing; it could be argued that there is simply a collection and succession of thoughts, but there needn’t be any single thing that persists between these thoughts. Perhaps Descartes should say ‘thoughts exist’ rather than assuming a self behind these thoughts. Empiricists might also argue that Descartes’ knowledge that a thinking thing exists isn’t synthetic knowledge because it derives solely from our knowledge of ourselves and the debate between the rationalists and empiricists centres on synthetic knowledge of the world outside one’s mind. Descartes’ arguments for the existence of God have also been strongly critiqued (see section 2.2.1 of The Definition of Knowledge section for criticisms of Descartes’ Trademark Argument and see Philosophy of Religion notes for criticisms of Descartes’ Ontological Argument). Descartes’ argument for the existence of physical objects and the external world depends upon the existence of God. Therefore, if his arguments for the existence of God fail, then so too does his argument for the existence of an external world. Descartes’ arguments for God and physical objects have also been criticised for being circular – known as, ‘The Cartesian Circle’. Descartes relies on clear and distinct ideas in order to prove the existence of God; however, he relies on the existence of God to know that clear and distinct ideas are true (that he is not being deceived).