Aquinas on Law --- [1]

advertisement

![Aquinas on Law --- [1]](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/010047693_1-8d6425a04d51173c29dbb2807de1644b-768x994.png)

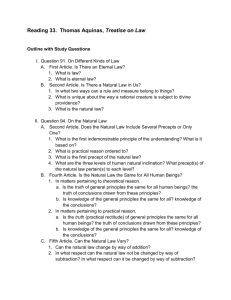

Aquinas Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274) -born to a noble family, but didn’t go for it... - became a prelate at age 17 -spent the rest of his life in study and writing... - incredibly influential.... [1] Aquinas - On Kingship • • • [2] General note on Aquinas: We have to finesse his biases as a servant of the RC church I will (try to) note when this matters and when it doesn’t... His official position is: • “God Governs the Universe by his Providence” [from summa contra gentiles] • • • - which might seem to commit him to Theocracy It doesn’t (cf. Augustine) - but it does bias him in that direction Obviously the question of how theology is related to political philosophy will be a main one. Stand by ... • “On Kingship” • Here Aquinas is giving advice to an actual ruler (the king of Cyprus) • Both his theological bias and his connection with the ruler in question might bias him in his argument... just something to bear in mind. Aquinas - on Kingship [3] • “Men in Society Must Be under Rulers” • So: why must men be under rulers? • 1. “A ship must have a helmsman” • [“a ship wouldn’t get to its destination if not guided by a helsman] • • • • • • • Q: is society a ship?? - reasons why we should not think so: - society is a whole lot of people - each is going various places - they’re not all going the same place - But ships necessarily go one way at a time... - society doesn’t have a unified set of sails, oars, etc. Aquinas • [4] “man has an end toward which all his actions are directed, being an intelligent being” • “So man needs someone to direct him” • • • • • • • [Problems: - back to the Aristotelian mistake: each man has “an end” (or a lot of ends) toward which he directs his actions not: we all have the same end toward which one super-ruler can direct us... “man is by nature a political and social animal” “he cannot provide for his life alone” [Agreed. That argues for social order of some sort - but why Political? Not so obvious ...!] Aquinas • • • • • • • • • • [5] “Community Breakup” 2. “If each provides only what is convenient for himself, the group “would break up” unless one had responsibility for the whole.” - so? “Private good and the common good are not the same” Aquinas: private good divides the community, whereas common concerns unite it. - does he mean “private goods” such as fried eggs and scuba diving? - or murder and arson? i) the first sort don’t seem to be a problem - we do have a common interest in getting our separate private goods achieved - market exchange, e.g., forwards this Aquinas [6] • “Community Breakup” • • • • • • ii) criminal action is indeed a problem, but privacy is not the source of it! - (murder is an interpersonal evil, not a good. Or does he mean, the murderer thinks it’s good for himself? True: but “public murder” (say, war) is even worse! - b) and, so what? - the “breakup” which is just different people doing different things is arguably good, not bad] Aquinas • • • • • • [7] 3. “The proper end of a group of free men is different from that of a group of slaves” That is because, as he notes, the free determine their own actions, whereas a slave, qua slave, belongs to another.” Where, then, do we go from here? Aquinas now proposes that “If a ruler directs his subjects to the common good, that is “right because appropriate” whereas if he aims at his own good, that is tyranny - unjust and perverse. (He astutely notes that tyranny by a few, or by many, for that matter, is also possible.) Aquinas [8] • • • • • 4. The Difference between Just and Unjust Rulers: If a ruler directs his subjects to the common good, that is right because appropriate, whereas if he aims at his own good, that is tyranny - unjust and perverse. [recall Thrasymachus] [note: Tyranny by a few, or by the mob, is also possible. But for the same (Aristotelian) reason: the ruler or rulers seeks his or their own good at the expense of the ruled.] • [Question: is he simply assuming the above? Or is he arguing for it?] Aquinas • • • • • • • [9] Government is “Natural”: 1) Whatever accords with nature is best 2) by nature government is by one - as the heart moves body (other cases: Queen* bees, and God, the Maker and Ruler of all) [Aquinas does not mention herds of cows, colonies of birds, and so on - where’s the “leader” there? [In any case, why should it matter what “nature” does? Aquinas • [10] 5. The problem of Tyranny [?] What if this one ruler is a bad one? (a tyrant...) • • The tyrant uses force to oppress instead of justice to rule. (as we’ve noted already, “ People can be oppressed also by a few, as in oligarchy, or by the mob, using the force of numbers to oppress the rich - thus even the whole people can be guilty of tyranny.” • [right: that’s a caution to democrats...] • • • • • • • • What to do about Tyranny? “A community must do its best to avoid giving the rule to one who will become a tyrant. But what do we do if he does become one? “If the tyranny is not extreme, it is better to tolerate it” [why? Because Taking action may be even worse (1) Even if opposition to the tyrant prevails, there tend to be deep divisions in the populace - which divides into rival groups. (2) And the one who aids the community in overthrowing the tyrant, very often, becomes himself a still worse one. Aquinas - on Kingship [11] • • • • • • What if the tyranny is unbearable? the best solution is not by private action of a few but by proceeding through public authority. The community together may depose the king or restrict his power; even if it agreed to obey him forever, this does not bind them if he abuses his power by becoming a tyrant Q: where does this leave us?? [Trouble is, the tyrant is the “public authority”! - there’s a problem here ....!] Aquinas [12] • 6. What is required for the good life of a group: • First, peace • Second “acting well by the community” • Third a sufficiency of necessities • Questions: • (a) are these in the right order? • [A suggestion: First, Third, Second [on the ground that wealth for all supports peace and enables acting well by the community ... ] Aquinas [13] • Peace • • • • • -> but perhaps peace is necessary and sufficient for “sufficiency” (1) Peace allows men to engage in work and exchange this promotes prosperity (2) - Also to form clubs, associations, churches, etc. (3) and enables them to work and become wealthier ... Aquinas • • • • • • • • • • • • [14] (2) “Acting well by the community”? what is that? [Isn’t this direction to peace??] [not reproduced in our anthology: the example of “community festivals” And: tennis clubs, symphony concerts, marathon runs .... Question: mightn’t NGOs do a better job at that? Question: is centralized community direction necessary for this? - that’s the question... Note: it’s easy to see why governments would want to get into the act - but should they?? Aquinas’ arguments don’t prove it at any rate - not yet! Aquinas on Law --- [15] Aquinas on LAW [from his Treatise on Law] • • 1. The Essence of Law: a measure of action by which one is led to act or refrain > Reason commands what is to be done to reach desired ends -> To be a law, a directive must be guided by reason • • • • 2. - and Community Parts ordered to wholes. Individual is a part (of the community). -> law must concern itself with the happiness of the community [Note that this doesn’t actually follow - ] • • • • No one person can make law - that is the responsibility of the whole people, - or of someone who represents the whole people. Private people give advice - which has no power of compulsion >> Law, however, compels. - That’s the difference! • Aquinas [16] • • 3. Aquinas’ famous “definition” of Law: Law is A Directive of Reason for the Common Good, promulgated and enforced by those “in charge of the community” • • • • • • (1) a Directive [or ‘ordination’] (2) of Reason (3) for the Common Good (4) Promulgated (5) and Enforced by (6) the Rulers of the Community • • [Comment: Ingenious and, in essentials, right] - The big question: what’s the Common Good? ... Aquinas • • • • • • • • [17] (3.1) a Directive tells somebody to do something When it’s a law, it tells everybody (in the community) to do something And it purports to stand above their individual desires But it “tells” rather than, say, pushing example: A tells B to go downstairs nonexample: A pushes B downstairs But A might tell B to go downstairs and threaten to push him if he doesn’t. • That would be how government “directs” Aquinas [18] • (3. 2) of Reason • • • • • • • [question: in what sense is law a directive “of reason”? - distinguish, for the present, between (1) “Laws of thought” [logic ] (2) “Laws of Nature” [Newtonian physics,e.g.] and (3) “human laws” - the question concerns the latter in the first instance. But, what about human laws? .... Aquinas • • • • • • • • • • [19] But, what about human laws? .... (i) If we mean that the laws are passed for good and excellent reason, and work to achieve their ends, then obviously not all human laws are rational (ii) Do we mean that the people who make them are highly rational? - Hah! (iii) But we could mean that we can ask, Is this law reasonable? - and expect a decent answer (which we often won’t get...) (iv) Or we might mean that there is reason why humans should have things like ‘laws’ -- if so, that’s important and might be true (but is surely discussable) - perhaps it’s a presupposition of legal institutions that there is good reason for them - but in that case, if there isn’t, then they flunk! (Whereas, the point of all this was to show that they pass!... wasn’t it?) Aquinas • • • • • • [20] 3.3. “for the common good” Q1. What is the status of this clause? [how “must” Law be “For” the Common Good? Suggested answer: It couldn’t be justified otherwise. [- which is normative -but it is intrinsic to the idea of law that this is the criterion to invoke.] Aquinas • • • • • • • • • • [21] (Q2) - Further Question: what is the “Common Good”? a. The sum of individual goods? or only b. A special subset of people’s goods -if so, which one?? Major question: - Good, according to whom? - The king? The Church? Or, Everybody? Suggestion: common good is what is in common - the same for all. But is there any such thing? That is a $640 billion question! And: why we should care about it? the fact that it’s “common” may help to answer that: if it’s common, we all care about it (don’t we??), because we each have a stake in it Aquinas • • • • • • • • [22] (3.4) Promulgated - Why promulgated? [because the point of laws is to direct the actions of beings who presumably need the direction i.e., they wouldn’t necessarily do what the laws direct them to do, on their own It would be irrational to expect Jones to do x if (1) he wouldn’t do it on his own hook, and (2) he had no information from anyone else to the effect that they expected him to do it [discussion question: how much promulgation?? Aquinas • • • • • • • • • • • • [23] Promulgation (continued) [discussion question: how much promulgation?? - page 1 in the Globe and Mail? - page 32, section H? - billboards? [discussion question: is ignorance of the law an excuse? [answer: if it’s the government’s fault, then YES] so, when is it the government’s fault?? [discussion item: Canada has several thousand laws on the books Nobody knows them all, including the legislators and lawyers - should we say that the promulgation criterion has been met? Or not? [lame conclusion: OK, this is an issue!] Aquinas • • • • • • • • • • • • • [24] (3.5) Enforced [discussion question: how much force? applied when? Applied how and by whom? * The Theory of Punishment now comes up Is punishment to visit retribution on offenders? Is it for deterrence? [that is: Is its purpose to reduce crime as much as possible? [what about execution for overtime parking?] Again: this is a big subject, brought up by Aquinas’ specification An issue: Is it a law if it’s not enforced? Suppose the average speed on road x is 120, the posted limit is 100, and the police arrest Miss Jones for doing 110? Does she have a complaint? note: at least, it’s an open issue whether a given law should be enforced as prescribed on a given occasion..... Aquinas [25] • (3.6) by the Rulers of the Community • Legal or moral? (or what?) • 6.1 Aquinas’ definition is legal in the first instance - most communities have governments ... • 6.2 But, it can be adapted [This is my proposal: • Moral law: the “rulers of the community” are everybody • [kings cannot “make” moral law...] • The tennis club might have a “rules committee” ... • Its results are the “laws” for members of that club • (but nobody else - which is why they aren’t “laws” in the full sense of the term) • [what about where Jones promises Smith that he will do x at time t?] [26] Aquinas’ Theory of Law (continued) • • • [distinguish from definition: A theory goes beyond definitions. It tells us how the thing works. In normative matters, it tells us what we should be doing...] • Four Kinds of Law: • 1. Eternal: governs “the whole community of the universe” (by • divine reason - which is not subject to time, hence Eternal • 2. Natural: Everything participates in (1) - is “imprinted • upon them” for rational creatures this is called the Natural law. • 3. Human: Human reason must proceed from the precepts of • natural law, to particular cases. These are called Human laws. • 4. Divine: [the source of this would be the deity himself... See next... • [note: shouldn’t the order be 4-1-2-3?] Aquinas • • • • • [27] [JN’s] Interpretation of the types of law in modern terms: Divine = from God Eternal = ‘Scientific’ [Physical (etc.) “Laws of Nature”] Natural = Moral Human = Legal • Aquinas’s Theory : • -> Each comes from the previous level • • • • • • [numbered in order of philosophical fundamentality] -> 1. Divine (From God )[in the first (a) of our two senses] -> 2. Eternal [“scientific”] -> 3. Natural [Moral] -> 4. Human [Legal] So there are three steps: 1->2; 2->3; 3->4 Aquinas [28] • • • • • • • 1. (1->2) Divine to Eternal: Divine = from God Eternal = ‘Scientific’ [Physical (etc.) “Laws of Nature”] Aquinas’ Thesis (1): Eternal Law is derived from Divine Law Q1: In what sense are the laws of nature laws? Do y need “decreeing”? Answer: Logically, No • • • • • But according to Theism, Yes [the point is that theism is not self-evidently correct here...] It makes no sense to talk of rocks - or anything - “disobeying” the Law of Gravity But moral and legal laws can be disobeyed (we wouldn’t need them if they couldn’t) • • • - Is it intelligible that some deity would “pass” the laws of nature?? not obviously . ... In general: God couldn’t both create the universe the way it is, and then • [but we haven’t time to go into this] “pass” some quite different set of “laws” for it Aquinas • • • [29] - How you would “prove” a Religious Theory of Things is an interesting question... [which, alas! - we don’t have time to discuss But the most important step in his theory is the next one: • Step 2: from Science to Morals • i.e., from (type 2) Eternal [laws of nature] to (type 3) • claim: “Natural” [i.e. Moral] Law is “founded on” the facts of the world (including facts about us) • -NOTE: the theory is not that God “passes” the Moral Law, directly (That is known as the “Divine Command” theory • Aquinas is not a Divine Command theorist • Agenda: • (a) why the Divine Command theory won’t do • (b) what’s involved in the Natural Law idea.... Aquinas [30] • (a) why the Divine Command theory won’t do • Discussion: ‘Moral’ • Can “moral laws” be “passed” (legislated)?? • Legislation (normally) happens at some time • [presumably God’s “legislation” would have happened “at the beginning”] - Aquinas [31] • • • • • Can “moral laws” be “passed” (legislated)?? No. Legislation: happens at some time So, is the following scenario possible? 1. murder is right up until Tuesday afternoon, March 4, -10,000 b.c. at 4:00? (and nothing else changes at that time) • 2. Then the Divine Legislature decrees that as of that time, it’s wrong! • (2a) Note: we are supposing that nothing else changes • • • • - i.e., people and the facts of life are the same before and after Does that make sense? [consider Moses bringing down the stone tablets with the “Ten commandments” on them...] answer: No. God would forbid murder because it’s wrong Aquinas [32] • • • • Divine Commands: the Euthyphro thesis [Plato’s dialogue Euthyphro discusses this... it’s not in our readings] Question: does God’s command make things right?? Or: does God command x because x is already right? • • Note: if the first is correct, presumably just any old thing could have been moral. God gets a nasty headache, so he decides to make daily somersaults morally obligatory! That picture makes no sense.... Thus the 2nd option is correct - and theological ethics is impossible • • • which amounts to saying that his laws are “eternal” - he just always wills them and that’s that. • BUT the question is whether God’s “will” has anything to do with it Aquinas [33] • Back to Aquinas’ theory: • (3) Moral laws are founded on Eternal Law [laws of nature] • I.e.: moral law is “founded on” the facts of the world • (including us) • A’s picture : • God creates the world • The world, being the way it is, is such that rational people, being the way they are, end up equipped with the Natural Law • [The Big Question: How?] Aquinas [34] • Step 2: Eternal to Natural [Moral] (continued) • • • • Options: (1) moral laws are simply laws of psychology (2) people have “native moral software” (3) ... what else... ? • • • • (1) Problem : you can’t “disobey” the Law of Gravity - If moral rules were like that, nobody could do anything wrong! - which is crazy. [morals are not intended to be useless!] (2) Aquinas leans toward (2): he says that moral laws are “promulgated” in that they are “written on all hearts”) • Problem: but (a) some “hearts” seem rather devoid of them; and • (b) people seem to differ about them! Aquinas • • [35] • • • - What to do? Aquinas’ idea: We can just “see” that things are right or wrong by looking at them and grasping their “essences” - e.g., 1. man’s organs have purposes P 2. therefore, pursuing P is morally what they ought to do... • • Requires “Natural Teleology” - things comes with purposes built in Does this work? No. Aquinas • • [36] Our nature tells us what we can do. But does it tell us what we ought to do? [Example: sex organs are “for” reproduction but they also work fine for entertainment... so, Why must we prefer the former to the latter??] Thomists say we ought not to use them for the latter unless we intend the former • Why would that be?? • -- suppose nature “tells us” to do x. • (a) does that make sense? • (b) Why should we listen to it?? • [Are appendectomies “unnatural”? • The fact that they achieve good ends can be taken to show either that they are natural after all ... or, that “unnaturalness” is irrelevant Aquinas • • • • • • • • • • [37] The right theory (according to me...) General idea: if “moral law” L is right, then there are facts about ourselves and our environments such that acting on L is the best response to this [question: best how? What makes it “best”? [rough answer: to promote the interests of those concerned (i.e., us....) In the case of moral law, we add: given that we are members of society.... But Aquinas has the bull by the horns in pointing to the difference between men and slaves.... Further interesting questions: [alas, no time to explore adequately] [example: Is Natural Law the Same for All? [his answer: basically, yes - but no in details ... So: as far as general principles go, they are the same for all, but for particular conclusions, we will have variability and exceptions. Aquinas on Law.2 -- (38) • (3->4) Human law: How and why derived from Natural law? [i.e., Step 3 in Aquinas’ program: = [Moral] to [Legal] • The thesis that legal laws are derived from moral laws can’t be that all human laws are morally right • - unless you play fast and loose with the definition • which Aquinas maybe does, when he says this: • “an unjust law is no law at all” [Aquinas got that from Augustine] • • “Every human law that is adopted has the quality of law to the extent that it is derived from natural law; insofar as it diverges, it is a corruption, not a real law.” Aquinas on Law (2) -- (39) • [Immoral laws]: • What is the significance of a legislated law’s being wrong? • - that it’s immoral? [obviously, yes. The question is, so what?] • Aquinas (remember) says we should put up with a LOT from our government (so does Socrates) • - put up with, how?? • [1] by not mounting a revolution: at what point do we start killing officials?? • [Aquinas maybe thinks: none....] • Or [2] is obeying the law, no matter what it’s like, morally obligatory?? [A. thinks not -- but makes the wrong exceptions: religious ones] Aquinas on Law (2) -- (40) • • • • • • • • • “An unjust law is no law” (continued) General conclusion: If we take ‘law’ to have normative impact, then “unjust laws are no laws” means that the unjust ones lack normative authority Note: It might still be prudent to obey them, even though they’re bad [But how bad may they be? And for how long must we put up with them?] Meanwhile: The thesis means that - If there is no valid reason to forbid people from doing x, then the Law should not forbid them - and, thus: (1) legislatures do wrong in passing them in the first place (2) people prima facie do no wrong if they disobey them Aquinas on Law (2) -- (41) • “An unjust law is no law” (continued) • • • • • • • • • Aquinas asks: Does Human Law Oblige in Conscience? and replies: “A law may be unjust in two ways: First by being contrary to human good; second, by being contrary to Divine good. “Laws of the first kind do not bind in conscience, but should be obeyed “in order to avoid scandal or disorder” But the second sort may “on no account” be obeyed. [comment: oh-oh! [obvious question: why would God allow people to do what’s contrary to “Divine” good in the first place??...] [and, who will judge this? (evidently: the priesthood...) • Aquinas on Law (2) -- (42) • Why human law at all? (continued) • • [that is: if the moral law is natural and self-evident, why do we then need a further body of legislated government-imposed law?] A’s answers: • [1]: “Some people are dissolute and prone to vice, and are not easily moved by words. They have to • • • • • • • • • be restrained from doing evil by force and fear. [note: this is Aristotle again ....] “That is the discipline of law, and laws that [restrain people from evil] are “adopted to bring about peace and virtue.” Two questions: (1) Why would this be a further accretion to natural law as it is? [Aquinas has said that the Natural law is “self-evident” - so why would it need “promulgating” by publishing it in the government’s law books??] (2) And why would government be necessary to do the punishing? [Why couldn’t just anyone participate in the enforcement of morals? - parents and friends, for example....] Aquinas on Law (2) -- (43) • Why human law at all? • • [that is: if the moral law is natural and self-evident, why do we then need a further body of legislated government-imposed law?] One possible answer: Co-ordination • • • • • • • Pure Coordination (ordinal utilities) B x y x 0, 0 1, 1 A y 1, 1 0, 0 Example: let x be “keep left”; y is “keep right” • • -> One way to resolve them is with a central decision-maker such as a king ... [But is it the only way??] Aquinas on Law (2) -- (44) • • • • • • • • • • When (and what) do we punish? Should Law “repress all vices”? “Human law is framed for the mass of men. “So it cannot prohibit every vice from which the perfectly virtuous abstain but only the more serious ones from which the majority can abstain” especially those that result in harm to others, such as homicide and theft [Question: are there any that don’t result in harm to others??] [and: what about the minority who can not “abstain”?] Evidently: the law prohibits all from doing x because x is harmful to others; and it applies its punishments to the few who can’t manage to refrain on their own [The good will abstain without threat of punishments; the bad will not] Aquinas on Law (2) -- (45) • The Letter of the Law: Is it binding? • Case of the “City Gates” • • Suppose a city under siege has a law that the gates be kept closed But suppose “the enemy is pursuing citizens on whom the city depends: it would be very harmful if the gates were not opened to them, even if that violates the letter of the law; Then the gatekeeper should open the gates, for it protects the common interest, as the legislator intended.” • • • • • • Aquinas thinks this really is exceptional: if there is no immediate danger, then it is not up to the individual to decide what is or isn’t useful to the city. That is the sole responsibility of the ruler, who has the authority. But The legislator cannot foresee every individual case. [..... interesting! [Question: why should it only be emergency or matters of extreme danger that make for exceptions?? How about jay-walking? (One of my favorite subjects!] Aquinas on Law (2) -- (46) • • Change in the Law Should Human Laws Ever be Changed? • • • • • Changing the law is a nuisance So law should be changed only when the common welfare is compensated for that harm. This happens either when (1) a substantial and obvious benefit is in sight, or (2) when there is urgent necessity because the old law produces manifest injustice or proves very harmful. [note: isn’t that a “substantial and obvious benefit”?] Aquinas on Law (2) -- (47) • - Religion, Again - • • • • • • • • • • • “The establishment of new dominion by unbelievers can in no way be permitted, for it endangers the faith.” (Dominion is a matter of human law; but the distinction of believers and unbelievers is a matter of divine law - which does not abolish human law (which is based on reason - not faith) > So, it is permissible for the Church to take unbelievers’ political power away, but it does not always do so. (?!) [No freedom of speech in this area!] Are the Rites of Unbelievers to be Tolerated? God, who is omnipotent and supremely good, yet permits some evils he could have prevented - when, if he did, a still greater good might be taken away, or still worse evils follow [This gets him into the age-old theological Problem of Evil: how can the above work?] • Should we tolerate Heretics? • • Heresy “deserves not only excommunication by the church, but indeed, death” But “the church is merciful and desires the conversion of those who are in error” • • But stubborn ones? No way! [they [comment: uh, huh ....] • may even be put to death] Aquinas on Law (2) -- (48) • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • This returns us to the subject of the Common Good - is there a good in common to believers and unbelievers? [Yes! - But A., who is biased by his religion, doeosn’t see it.] Political Issues about Religion: Conservative vs. Liberal 1. Religion is Publicly unprovable (i.e., not, in Aquinas’ sense, Rational) 2. There are lots of different religions, and many people have no religion. 3. But these people are all in “the community” (e.g. Canada) Therefore 4. Aquinas’ objections to “heresy” should be regarded as contrary to the idea of the COMMON Good. To say what Aquinas does is to ask for Religious Wars: Each religion will try to exterminate members of the others as “heretics”. [or are heretics only apostates? Now the question is: May the state allow a sect to compel its own members to remain members indefinitely, against their will?] Our Answer: No way! The proper solution is RELIGIOUS LIBERTY: Nobody is allowed to exterminate anybody for religious reasons. (More general principle: the Separation of Church and State: NO public laws may be made for religious reasons) Aquinas on Law (2) -- (49) • War • “Whatever natural reason has established among men is observed by all • • • • • • • • • • • nations and is called the law of nations. “jus ad bellum”[When does jusice permit war?] “Three conditions for a just war. First: the ruler must have authority to make war. No private person has this right, but only him to whom the commonwealth is entrusted. Second: a just cause is required. examples: “to avenge injuries, or secure the return of what has been unjustly taken.” Third: those making the war must have right intention, to achieve some good or avoid some evil. Even if a war is initiated justly by legitimate authority, it can become unjust by evil intentions. Aquinas on Law (2) -- (50) • • • • • • • • • • [Our text does not have this further part of Just War theory, but introduces this at 64.7 on self-defense] [The “double effect”: suppose you pursue a good cause but, without intending them, some evils befall others in the process? - double effect says that as long as the bad effects aren’t too bad, you may proceed] [There are also restrictions on what you can do in fighting a war: “jus in bello” (justice in the conduct of war) 1. Noncombatants are not to be targeted 2. Soldiers not to be sacrificed for hopeless causes 3. Minimum force: “proportionality” 4. The object is always a subsequent just peace -- so, no killing for the sake of killing, or out of malice Aquinas on Law (2) -- (51) • • • • Sedition against Peace - Is opposed both to justice and to the common good However, tyrannical government is unjust for the same reason: it is directed not to the common good but to the private good of the ruler. • note on sedition: “organizing or encouraging opposition to government in a manner (such as in speech or writing) that falls short of the more dangerous offenses constituting treason.” • To overthrow tyrannical government is not sedition, • - unless done so badly that society suffers more from the disorder than it did from the tyrant. • It is the tyrant who is guilty of sedition: • he spreads discord and division in order to bring people under his evil control more readily • And that harms the community. Aquinas on Law (2) -- (52) • • • • • • • • • Self-Defense and “Double Effect”: Defending oneself has two effects: (1) saving one’s own life, (2) killing the attacker. (1) is clearly right - but not if the force used was not proportionate to the end (Moderation required) . But (2) it is not lawful for a private person to intend to kill another -- only those in public authority may do that. Soldiers fighting enemies, officers combating robbers, yes - though not if motivated by private hatred. [the important distinction between morality as inner control of the soul, and as external public control....] Aquinas on Law (2) -- (53) • • • • • • • Can a Private Person kill a Criminal? (Aquinas on Gun Control) It is permissible to kill a criminal, if this is necessary for the welfare of the community. But only rulers have this right, not private persons. [note: Is this credible? If somebody threatens my life, I have to wait till the police arrive? [“Kindly wait with your proposed murder while I phone 911, OK?”] - a VERY large issue is raised here. Aquinas on Law (2) -- (54) • • • • • • • • • • • • • Suicide “is always totally wrong.” argument: (1) everything loves itself, and so should naturally seek to preserve itself; (2) man is part of community: if he kills himself, he harms the community (3) Life is a gift of God to man, and subject to his power alone. [replies: (1) they kill themselves because they “love themselves” (2) does the community own its members? (3) if A gives x to B, as a gift, doesn’t B get to decide what he wants to do with x? ... [in any case, is he talking personal morals, or public law??] Aquinas on Law (2) -- (55) • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • Private Property > From their nature, external goods are subject only to God But from the point of view of use, we have a natural property right - reason and will make such things beneficial. - Natural dominion over the rest of creation - “image of God” ... Two capacities re externals. First, to care for and dispose of them. In this interest, private property is obviously legitimate, for three reasons. 1. Everyone is more concerned to take care of what belongs only to him than of what belongs to everyone or to many .. 2. Human affairs are more efficiently organised if care of each thing is an individual responsibility 3. Peace is better preserved if each has his own - quarrels arise among common owners We should make use of external things for the community good and be ready to share them with others in cases of necessity. [note that his three conditions are got from Aristotle....] Aquinas on Law (2) -- (56) • • • • • • • • • • • • The “Needy” (Aquinas on the Welfare State) In cases of necessity, everything is common property. Then it is not a sin to take the property of another. “Lower ranking things are meant to supply the necessities of men. So division and appropriation of property by human law does not prevent its being used for the needs of man. “what anyone has in superabundance ought to be used to support the poor” But if the needy are many and cannot all be supplied from the same source, the decision is left to each individual as to how to manage his property so as to supply those in need. If there is urgent and clear need then a person may legitimately supply his need from the property of someone else. Strictly speaking, such a case won’t be theft. Aquinas on Law (2) -- (57) • • • • • • • • • • Profit Two sorts of business exchanges (1) “natural and necessary” - one commodity for another, or for money needed to buy what is in turn needed - praiseworthy, for it serves natural needs (2) money for money, or for goods to make money - rightly condemned trade in itself has “a certain quality of baseness” - “does not of its own nature involve an honorable or necessary end” [Aristotle again] Aquinas on Law (2) -- (58) • • • Drunkenness A sin to willingly and knowingly deprive oneself of the use of one’s reason (which “enables one to act virtuously and avoid sin”). • • • • • • • Virginity > Giving up material possessions to contemplate truth is O.K. > So, abstaining from bodily pleasures for similar purposes is O.K. [Example: “holy virginity” - in order to “contemplate the divine” >> We must all eat - but as regards procreation, it is sufficient if some do it, while others abstain to “devote themselves to the contemplation of the divine and the improvement and welfare of mankind”. • • • [Here Aquinas anticipates the idea of “Universalizability”: If act x is such that is everyone did x, that would be disastrous, can it be O.K. to do x? Answer: Yes, if Division of Labor will do the job.] Aquinas on Law (2) -- (59) • • • • • • • • • • • • • • Women - Intended by nature to be directed to the work of procreation (and, of course, “naturally subject to man because by nature man possesses more discernment of reason” - right? ....) [This brings up the subject of “natural intention” - which is nonsense (unless, of course, we read theology into it: God can have intentions regarding nature; but it itself cannot) Important Distinction: (a) “intended” by nature (requires Anthropomorphism) (b) “fitted” by nature - Makes perfectly good sense: one’s natural characteristics can be useful for some things more than others. Women are “fitted” for having children in a way that men obviously aren’t. But it doesn’t follow from the fact that you are able to do x that you therefore jolly well ought to!] Aquinas on Law (2) -- (60) • • • • • • • • • • • The “State of Innocence” [Biblical idea: The condition of people, depicted in the Book of Genesis, prior to the “Fall from Grace”] [Why mention this quaint “issue”? Because it gives A. an opportunity to consider the moral status of natural differences, independently of theology. Later writers will discuss a “state of nature”] Would we all have been equal there? (1) There have would have been many differences: of the sexes, in knowledge or goodness, strength, beauty, etc. (2) BUT, No master/slave Relation It is against nature for one rational being to have dominion over another. But, Unnatural things are appropriate as punishments slavery was introduced as a punishment for sin ... Aquinas summarized (61) • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • (1) Foundations of government: - not too good - appeals to a bad analogy (the “ship of state”) - to natural organization (doesn’t work) - and to the need for community (right, but doesn’t clearly imply government) (2) General Idea of Law: “directive of reason for the common good” - this is great! - but which idea of “common good” do we use? - here he’s guilty of religious bias Distinguish conservative from liberal view of common good: conservative: somebody else imposes it liberal: each person is the “authority” on what’s good for him. Aquinas is a conservative ... (3) Foundations of Morals: important progress -> morals is to be founded on the way things are -> but how is it so founded? What is “natural law” beyond the above claim? [Aquinas does not get into Social Contract - thinks that laws come directly from “things” - this won’t work] Aquinas summarized (62) • • • • • • • • • • • • • • (4) Human Law: to be founded on natural morals -> not clear what the implication is: --> that there can be bad laws --> but we can’t do much about them (he’s very conservative about this) - Introduces the question of obligations to the “needy” - his own view unclear -- does it support the “welfare state”? - not good on religious freedom - but improvable! (5) Civil Law: not too many civil rights - due to religious bias e.g. the government is to allow the church to execute heretics... allows prostitition and booze (?) doesn’t allow general free speech.... (6) International Law Just War theory... an important contribution In general: Sets the stage for modern political thinking....