Adaptations for Digging & Burrowing

advertisement

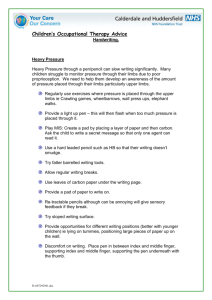

Adaptations for Digging & Burrowing Ch. 17 Digging/Burrowing Common widespread behavior For finding food, storing food, hiding eggs/young, temporary/long-term shelter Performed with hands, feet, head or some combination; occasionally with the mouth or neck (Pituophis sp.) Salamanders Least specialized diggers of amphibians Many use pre-existing burrows or Enlarge natural crevasses w/ shovel-like head motions or lateral undulations Tiger salamanders apparently best diggers Survival in arid environments Dig w/ muscular forelimbs, alternating every 3-10 strokes No apparent morphological adaptations Feet-First Burrowing Fogs Vast majority of frogs burrow hindfeet first Head raised, 1 leg fully flexed, then soil immediately beneath & behind feet thrown posteriorly or onto frog’s back Enlargement of inner metatarsal tubercle (integumentary projection on ventromedial surface of foot) Increased size & robusticity of prehallux (skeletal support of inner metatarsal tubercle) Feet-First Burrowing Frogs Relatively short hindlimbs where tibiofibula is shorter than femur Mexican burrowing frogs (Rhinophrynus dorsalis) loses a phalanx from 1st digit & remaining phalanx morphologically converges on distal prehallux Thickened, rasp-like skin beneath spade-like elements No apparent burrowingmorphologies of pelvises Head-First Burrowing Frogs Most information comes from Hemisus marmoratus & Arenophryne rotunda Frog thrust snout into ground, then uses forelimbs to excavate around head Forelimbs may be used alternately, synchronously, or unilaterally Once buried, hindlimbs may be used to propel frog forward Head-First Burrowing Frogs Humerus, radioulna, & fingers short & robust Increased area of attachment for muscles on humerus (ventral humeral crest) Decreased mobility in finger due to changes in shape & number of phalanges & intercalary cartilage (where present) Coracoids longer & more robust (provide greater surface area for muscle attachment), and are more obliquely positioned relative to long axis of body Caecilians Most highly adapted amphibian burrowers, but are poorly studied All lack limbs (facilitates burrowing) Fossorial taxa burrow w/ their heads Rigid, heavily ossified skulls Turtles Digging is common among turtles especially tortoises, also underwater Daily shelter, hibernation, nesting Burrows usually dug w/ forelimbs, egg pits dug w/ alternating scooping w/ hindlimbs Body pits prior to egg pits dug w/ forelimbs (alternating or synchronous), hindlimbs (alternating), all 4 limbs (diagonally alternating) or some sequential combination Turtles Following based on Gopherus, an extensive tunneler Distal phalanges enlarged to support large, flat nails Forefeet short, broad & stiff Reduced length & number of phalanges except distal phalanges Close-packed, cuboidal carpal elements Crocodilians All bury eggs on land & some dig young out upon hatching, some burrow underground during extreme cold or drought, & one (Crocodylus palustris) may bury surplus food May dig w/ hindlimbs (main method for egg chambers), forelimbs (main method for excavating hatchlings), snout, & jaws (in grassy areas) No obvious morphological adaptations All features seem plesiomorphic or evolved for other purposes Lepidosauria More digging & burrowing taxa than any other major clade of vertebrates, & almost all at least somewhat capable of digging Most quadrupedal species scratch w/ forelimbs alternating after several strokes Some may use head (weak forelimbs or burrowing into soft sand) Lepidosauria Morphological specializations for limbdigging rare Most specialized species: Strongly webbed hand/feet Palmatogecko rangei Likely evolved for locomotion over loose sand Cartilaginous paraphalanges strengthen webbing more proximal than nonburrowing species Lepidosauria: Amphisbaenians Head-burrowers; all but 3 species of Bipes completely limbless Limbed species use large forelimbs (no external hindlimbs) to dig when initially entering ground; afterwards burrow w/ head Lepidosauria: Amphisbaenians Forelimbs are short, wide, & large relative to body Zeugopodium short relative to stylopodium Digits stout & roughly same length Loss of phalanges + gain of phalanx in 1st digit for some sp. Hand is broad w/ large claws Pectoral girdle positioned unusually close to head Loss of limbs helpful for burrowing, but apparently evolved as a result of body elongation Mammalian Scratch-Diggers Most common form of digging in mammals Variable degrees of morphological adaptations (many have none) Rapid, alternating strokes of clawed forelimbs in predominantly parasagittal plane Many rodents use large incisors to help loosen soil, & some may use head & feet to move loosened soil Mammalian Scratch-Diggers Enlarged sites of attachment for forelimb muscles used in digging Sites of attachment shifted, length of elements changed to increase mechanical advantage Deltoid tubercle of humerus positioned far from shoulder, long olecranon process (sometimes accompanied by shortening of radius), shortened manus Articulations may be altered to stabilize joints posteroventral portion of scapula, acromion process long?, deltoid tubercle of humerus, median epicondyle, long olecranon process Long acromion may limit lateral rotation of humerus, vertically oriented keel-&-groove articulations in digits limit lateral movements Some bones shorter/stouter/more robust Short & stout humerus w/ thicker cortical bone around diaphysis, shortened metacarpals & phalanges, large & robust distal phalanges/claws Mammalian Scratch-Diggers Burrowers may brace themselves by pushing hindlegs out laterally against burrow walls Pelvis roughly horizontally oriented, nearly parallel w/ vertebral column, & acetabula positioned high – prevents torsion when bracing Elongated sacrum – increased stability for pelvis = greater forces generated by hindlimbs? Hook-&-Pull Diggers Used exclusively by anteaters to open ant/termite nest during foraging Large claws on 2nd & 3rd digits hooked into crack/hole, then fingers are strongly flexed & the arm is pulled towards body Hook-&-Pull Diggers Sites of muscle attachment enlarged to accommodate larger muscles: postscapular fossa (limb retractor), median epicondyle (3rd digit flexor) Distal tendon of largest head of the triceps muscle merges w/ tendon of M. flexor digitorum profundus, changing function to flex the 3rd digit Shape of bones changed to provide mechanical advantage: larger median epicondyle, notch in median epicondyle acts as a pulley for medial triceps tendon Hooking digits large & robust Keel-&-groove articulations in digits limit lateral & torsional movement Possible Theropod Analog Mononykus Cretaceous Mongolia Single large functional claw Palms face ventrally Joints of manus limit movement to parasagittal plane All apparently convergent w/ mammalian hook-&-pull diggers Senter (2005) Humeral Rotation Diggers Best known in moles & shrew moles, may also be used by monotremes Lateral thrusts of forefeet almost entirely through long-axis rotational movements of humeri Both arms may be used synchronously (loose soil) or one at a time Humeral Rotation Diggers Scapula oriented almost horizontally = anterior displacement of forelimbs, and humerus oriented obliquely = forefoot positioned laterally Increased area of attachment for enlarged muscles Area of origin on scapula for M. teres major Manubrium long & ventrally keeled for pectoral muscles Processes & articulations reoriented for mechanical advantage & passive flexion/rotation Increased distance between humeral head & teres tubercle Deflection of tendon of M. biceps brachii through tunnel = passive rotation of humerus during recovery Fossa at distal end of medial epicondyle far lateral to axis of rotation = passive flexion of manus Humeral Rotation Diggers Glenoid has elliptical articulation w/ humerus to stabilize joint Radius, ulna, metacarpals, & proximal phalanges shortened (mechanical advantage) & robust Distal phalanges enlarged to support large broad claws Large radial “sesamoid” on inner edge of forefoot increases width of hand Humeral Rotation Diggers Hindlimbs used for kicking back loose soil in deep burrows & for bracing against burrow walls as in scratch-diggers Pelvis elongated & nearly parallel to vertebral column, acetabula raised Pelvis fused to sacrum in up to 3 places Hindlimbs shorter (shorter tibiofibula & pes) = increased force generated + presumed increased efficiency in tunnel locomotion Aquatic Adaptations in the Limbs of Amniotes Ch. 18 Aquatic/Amphibious Amniotes Many different taxa independently evolved aquatic or semi-aquatic lifestyles Multiple types of land-to-water transitions are easy to make & readily advantageous (as opposed to land-to-air transition) Many animals may be good swimmers &/or spend much of their time in the water & have little/no aquatic adaptations Mammals May primarily wade or swim May swim w/ forelimbs, hindlimbs/tail, or both Limbs/tail may move in vertical plane or horizontal plane Limbs may provide forward thrust through drag-based paddling or by generating lift (fin shaped like hydrofoil) Mammals: Few Swimming Adaptations Shallow waders: walk in shallows, generally w/o submerging Deep waders: walk on substrate beneath surface of water Tapirs, moose, etc. Little or no limb adaptations Hippopotamus May have larger &/or denser bones to counter buoyancy Quadrupedal paddlers Most terrestrial species May have webbed feet Mammals: Pelvic Swimming I Alternating pelvic paddling (beaver): alternating flexion & extension of hindlimbs in vertical plane Alternate pelvic rowing (muskrat): alternating flexion & extension of hindlimbs in horizontal plane Both may have large feet w/ webbing (or long hairs) Muskrat also has feet shifted to be perpendicular to plane of motion Lateral pelvic & caudal undulation (giant otter shrew) propelled mainly by sinuous movements of tail & adjacent vertebra Hindfeet play secondary role Fewer limb specializations than rowers/paddlers; tail may be mediolaterally flattened Mammals: Pelvic Swimming II Pelvic oscillation (phocids): Feet move in horizontal plane w/ plane of feet held vertically, & most power provided by vertebral column Ilium is short & anterior part is laterally deflected where propulsive muscles in back attach; ischium & pubis are long Femur is short, but robust where muscles attach Tibia & fibula are long often w/ a synostosis proximally Feet are symmetrical w/ 1st & 5th toes relatively large Forelimb morphology reflect terrestrial locomotion Mammals: Pelvic Swimming III Simultaneous pelvic paddling (otters) Dorsoventral pelvic undulation (sea otter) Synchronous movement of hindlimbs in vertical plane Similar limb morphology to APP: large, webbed feet Tail & back muscles also participate Feet are asymmetrical hydrofoils (digit 5 longest) thrust provided during upstroke & downstroke Femur, tibia, & fibula short Dorsoventral caudal undulation (giant otter) Flattened tail + webbed fingers/toes Limbs generalized since tail is used to swim Mammals: Pelvic Swimming IV Caudal oscillation (Cetacea & Sirenia) All propulsion by paddle/fluke shaped tails, no external hindlimbs Forelimbs in cetaceans used for steering & stabilizing Elbow, wrist, & fingers immobile Fingers asymmetrical w/ leading edge longest, displaying hyperphalangy Mammals: Pectoral Swimming I Alternating pectoral paddling (polar bears) Alternating movement of forelimbs in vertical plane Morphology same as for terrestrial bears Alternating pectoral rowing (platypus) Alternating movement of forelimbs in horizontal plane Presumably swim by humeral rotation as in walking Forelimb of Ornithorhynchus resembles that of moles (humeral rotation diggers) w/ webbed feet Mammals: Pectoral Swimming II Pectoral oscillation (Otariidae) Forelimbs provide lift during upstroke & downstroke Forelimbs are powerful & far back on body Humerus, radius, & ulna short Hand long, asymmetrical (thumb longer & more robust) flipper Cartilaginous elements on distal phalanges lengthen fingers beyond nails Hindlimbs used in steering & terrestrial locomotion Femurs are short Feet are long, symmetrical (large 1st & 5th digits) & webbed Birds Many species of birds evolved to live in & around water Three functionally distinct regions (“locomotor modules”): pectoral, pelvic, & caudal Aquatic adaptations involve either pelvic or pectoral regions w/out significantly affecting the other region Bird: Pelvic Swimming I Wading A large number of birds live in close association w/ water, but don’t swim May have longer, broader toes to distribute weight &/or long legs to wade deeper Alternating pelvic surface paddling (ducks) Float on surface & paddle w/ webbed feet Some may do limited diving – short, laterally held femur, tibiotarsus long & parallel to vertebra, knee extensions limited, & ankle joint at level of tail Birds: Pelvic Swimming II Alternating pelvic submerged paddling (loons, hesperornithiformes) Lateral pelvic undulation (grebes) Paddle backwards underwater Webbed feet are reoriented far back on body Feet provide lift; toes are asymmetric & each has a hydrofoil cross-section Quadrupedal surface paddling (flightless steamer ducks) Combine simultaneous beats of wings w/ alternating beats of hindlimbs on the surface Birds: Pectoral Swimming Simultaneous pectoral undulation (auks, penguins, etc.) Underwater flying: movement of wings similar in air & water Combining aquatic & aerial flight reduces efficiency for both Reduced wing area (shorter) = high wing loading Flightless birds maximize efficiency for swimming Reduced range of motion in joints; reduced internal wing musculature Wing bones are short, stiff, flattened, & skeleton is dense Wings positioned near midbody Head, tail, & feet used for steering = feet placed more posteriorly Reptiles Nonmammalian & nonavian amniotes Most obligatorily aquatic taxa are extinct & have relatively poorly understood evolutionary histories Most extant taxa & probably basal amniotes are/were facultatively aquatic Reptiles: Primitive Aquatic Locomotion Wading/bottom walking: many reptiles wade into water to feed w/o swimming Some species w/ dense bodies may walk underwater such as some freshwater chelonians & apparently some placodonts Lateral axial undulation & oscillation (crocodiles & squamates) Propulsion provided by tail & to a lesser extent body In slow swimming limbs are mainly used for maneuvering; fast swimming limbs are generally held immobile against body More amphibious forms (crocodilians, phytosaurs) may have shorter, broader limbs Reptiles: Obligatorily Aquatic Taxa Lateral axial undulation & oscillation Mosasaur & ichthyosaur limbs evolved into fins w/ shortened long bones, reduced flexibility & hyperphalangy Ichthyosaurs caudal fins convergent w/ cetaceans & sharks limbs may show change in number of digits & loss of digit distinction bones lightweight = buoyancy control or energy conservation (less inertia) Sea snakes live entire lives in water Limblessness advantageous for streamlining Evidence that snakes evolved from aquatic taxa: fossils w/ aquatic morphologies (pachyostotic ribs, flattened tail), presumed close relatives that are aquatic (mosasaurs) Reptiles: Limb-Propulsion I Rowing Freshwater turtles row w/ 4 limbs w/ webbed feet in alternating diagonal strokes Pachypleurosaurs also apparently used this method & added tail undulations Nothosaurs had relatively long (hyperphalangy), broad (long bones widened, space between radius & ulna), & stiffened forelimbs Reptiles: Limb-Propulsion II Quadrupedal undulation (plesiosaurs) Lift-based thrust of all limbs w/ comparable size & structure Laterally projecting hydrofoil limbs Massive femur/humerus; reduced zeugopod & wrist/ankle elements, loss of elbow/knee & wrist/ankle joints, & hyperphalangy Pectoral undulation (sea turtles) Lift-based propulsion w/ strong synchronous beats of long hydrofoil forelimbs Hindlimbs used for steering & locomotion on land Sesamoids & Ossicles in the Appendicular Skeleton Ch. 19 Sesamoids & Ossicles Ossicles: any overlooked appendicular skeletal elements Highly variable size, shape, & position within & between taxa Often overlooked by anatomists, but important for pathology & biomechanical issues Intratendinous element: initially develop within a tendon or ligament (including sesamoids) Periarticular element: adjacent to a joint/articulation but not initially within a tendon or ligament Sesamoids ‘Sesamoid’ often used as a wastebasket for any small & unusual skeletal elements Sesamoid: skeletal elements that develop within tendon or ligament adjacent to an articulation or joint Relatively small & ovoid in shape Frequently have an inconstant distribution Sesamoid Diversity & Distribution Oldest known example (Permian) next to digit joints on palmar side of manus in captorhinids Oldest example (late Triassic) on a turtle (generally extant taxa don’t have them) on dorsal side of manus & pes Similar sesamoids also known in pterosaurs, a dinosaur (Saichania), lizards, birds, mammals & some anurans Ulnar patellas found in some pipid anurans, birds, mammals & most squamates Oldest knee sesamoid (mid-Triassic) found in Macrocnemius bassanii Tends to replace olecranon process in birds & lateral epicondyle in tree shrews & a bat (Rousettus) Also found in an anuran, some lizards, mammals & birds Tarsal sesamoids found in anurans, birds, lizards & primates Patella & Patelloid Patella: relatively large, well-ossified sesamoid cranially adjacent to distal end of femur Predominant sesamoid for study: biomechanical, orthopedic, pathological & evolutionary Constant in most lizards, birds, & mammals Absent in nonavian archosaurs, turtles & most marsupials Patelloid: more proximally positioned sesamoid of fibrocartilage Found in some marsupials, various placental mammals, a crocodilian & a turtle May co-occur w/ patella Patella/Patelloid Histology Mature patella consists of lamellar cortex and a trabeculated core w/ hyaline cartilage lined articular surfaces Chondrocyte-like cells of patelloid more disorderly than in the patella Patella Development Most true sesamoids develop through endochondral ossification The patella presumably starts as a cluster of cells w/in quadriceps-patellar tendon, then undergoes chondrification to form hyaline cartilage mass Unlike other sesamoids, patellas ossify early in ontogeny and develop in absence of mechanical stimuli Though mechanical stimuli necessary for regeneration (dogs) & to stimulate underdeveloped patellas in humans Recent research suggest LMXIB plays a role in patella development & dorso-ventral limb patterning Hoxa9/Hoxd9 and Hoxd9/Hoxd10 mutants result in misshapen & displaced patellas Traction Epiphyses Bony projections of insertion for a tendon/ligament that develop independently of the limb element Proposed to be sesamoids incorporated into long bones, or sesamoids are disarticulated traction epiphyses, or that both ossicles are completely separate Evidence in favor of the 1st hypothesis: In some mammals & birds the tibial tuberosity is derived from an independent condensation originating from w/in patellar ligament In some birds the patella is also incorporated into the hypertrophic cnemial crest Mineralized Tendons & Ligaments Found in various tetrapods, most notably birds Tend to be slender, elongate & terminate in advance of joints Development based off of studies of the domestic turkey Tenocytes (fibroblasts) of tendons hypertrophy & adopt a stellate morphology followed by hypertrophic tenocytes producing vesicles containing calcium & phosphorus = associated w/ earliest appearance of mineralization Lunulae Periarticular ossicles of the knee & other synovial joints, nested within the menisci They form osseous wedges w/ a crescentic morphology May serve protective & biomechanical roles, such as resisting compressive forces or acting as a fulcrum Lunulae Diversity & Distribution Best known in knee, though also found in other joints such as the wrist & ankle Reported in lissamphibians, squamates, birds, & a variety of mammals Very common in nonophidian squamates; up to 5 elements in an individual Knee lunulae very common in rodents Lunulae Development & Histology All exists as hyaline cartilaginous precursors & ossify after birth/hatching In humans, lunulae most often a result of injury or pathology Experiments w/ chick embryos suggest that development of menisci (& therefore lunulae) is dependent on movement of limbs & may result from biomechanical induction Haines (1942) hypothesized that lunulae form when menisci reach surpass a threshold size Outer layer made of lamellar bone & inner layer is cancellous bone with or without marrow Problematic Sesamoids & Ossicles Definitions of sesamoid & lunulae require knowledge of where the elements form during skeletogenesis; many ossicles only known from mature individuals The panda’s “thumb” may be a true sesamoid, a remodeled periarticular ossicle, or a neomorphic derivitive of the carpal series Other examples include: the “panda’s toe” (enlarged tibial “sesamoid”) “sesamoids” associated w/ digits in human manus (tendons & ligaments attach secondarily) Rods & extensions that support wings/membranes of bats, gliding mammals & pterosaurs (pteroid) Biomechanics Most explanations for sesamoids emphasis potential current or past biomechanical function Sesamoids & ossicles are most common in areas subject to friction, compression or torsion Known to sometimes occur in response to injury Connective tissue known to respond to compression/tension by altering ECM composition, fiber orientation, cellular morphology & cellular orientation Osteogenic index developed to predict the likelihood & position of sesamoid formation under different stress regimes