Parallel Lines Design Construction Pty Ltd v Bevins [2014]

advertisement

![Parallel Lines Design Construction Pty Ltd v Bevins [2014]](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/010045030_1-88251b7511455f9cc95a1bc932a22d49-768x994.png)

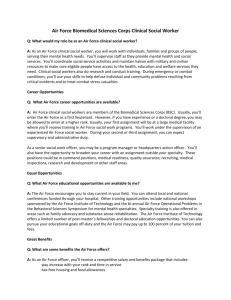

Issue 8: August 2014 On Appeal Welcome to the 8th issue of ‘On Appeal’ for 2014. Issue 8 – August 2014 includes a summary of the July 2014 decisions. These summaries are prepared by the Presidential Unit and are designed to provide a brief overview of, and introduction to, the most recent Presidential and Court of Appeal decisions. They are not intended to be a substitute for reading the decisions in full, nor are they a substitute for a decision maker’s independent research. Please note that the following abbreviations are used throughout these summaries: ADP AMS Commission DP MAC Reply 1987 Act 1998 Act 2003 Regulation 2010 Regulation 2010 Rules 2011 Rules Acting Deputy President Approved Medical Specialist Workers Compensation Commission Deputy President Medical Assessment Certificate Reply to Application to Resolve a Dispute Workers Compensation Act 1987 Workplace Injury Management and Workers Compensation Act 1998 Workers Compensation Regulation 2003 Workers Compensation Regulation 2010 Workers Compensation Commission Rules 2010 Workers Compensation Commission Rules 2011 Level 21 1 Oxford Street Darlinghurst NSW 2010 PO Box 594 Darlinghurst 1300 Australia Ph 1300 368018 TTY 02 9261 3334 www.wcc.nsw.gov.au 1 Table of Contents Court of Appeal Decision: Inghams Enterprises Pty Ltd v Sok [2014] NSWCA 217 ................................................... 3 WORKERS' COMPENSATION - appeal to Deputy President - errors of fact alleged against arbitrator - appeal limited to any error of fact, law or discretion - whether Deputy President failed to exercise appellate jurisdiction by restricting inquiry to errors of law whether Deputy President failed to engage with the evidence to determine whether there were any errors of fact – 1998 Act, s 352 .......................................................................... 3 WORKERS' COMPENSATION - jurisdiction of Workers Compensation Commission dispute over liability for weekly payments of compensation - no determination of a dispute over a "work capacity decision" by an insurer permitted - decision by insurer to dispute liability not a "work capacity decision" - whether jurisdiction excluded over matters which fall within the description of a "work capacity decision" - effect of transitional provisions – 1987 Act, ss 43, 44, Sch 6 Pt 19H cl 3, cl 14 - 2010 Regulation Sch 8 cl 3........................ 3 Presidential Decisions: Hills v Pioneer Studios Pty Limited (No 2) [2014] NSWWCCPD 42 .................................. 6 Section 4 of the 1987 Act; injury arising out of or in the course of employment; injury received during interval between discrete periods of work; employer’s inducement or encouragement of worker to be at a particular place during such interval; injury received at that place and by reference to that place; employment caused or to some material extent contributed to injury; injury arose out of and in the course of employment; s 9A of the 1987 Act; employment a substantial contributing factor to injury ................................................ 6 Trustees of the Society of St Vincent de Paul (NSW) v Maxwell James Kear as administrator of the estate of Anthony John Kear [2014] NSWWCCPD 47 ................... 10 Subarachnoid haemorrhage suffered at work after “near miss” riding a motor scooter to work; whether worker received a personal injury on a journey to which s 10 of the 1987 Act applies; meaning of “personal injury”; whether “shock” is a personal injury; whether elevated blood pressure is a personal injury; absence of evidence ................................. 10 Rodger W Harrison and Peter L Siepen t/as Harrison and Siepen v Craig [2014] NSWWCCPD 48 ................................................................................................................. 13 Drawing of inferences on injury in the absence of expert medical evidence; judicial obligation to make findings of fact on proved evidence; circumstances in which the Commission’s members may rely on general knowledge acquired in their capacity as members of a specialist tribunal; interlocutory decisions ................................................. 13 Boral Recycling Pty Ltd v Figueira [2014] NSWWCCPD 41 ............................................ 16 Finding of no current work capacity; weight of evidence; relevance of worker’s applications for full-time employment; assessment of medical evidence; s 32A of the 1987 Act; application of principles in Hancock v East Coast Timber Products Pty Ltd [2011] NSWCA 11; 80 NSWLR 43; alleged failure to give reasons .......................................................... 16 Iqbal v Hotel Operations Solutions Pty Ltd [2014] NSWWCCPD 45 .............................. 19 Interlocutory orders; leave to appeal; dismissal of proceedings by Arbitrator for want of prosecution pursuant to s 354(7A)(c) of the 1998 Act; failure to comply with an Arbitrator’s directions; failure to properly particularise a claim for permanent impairment compensation ........................................................................................................................................ 19 Secretary, Department of Family and Community Services v Victoire [2014] NSWWCCPD 44 ................................................................................................................. 21 Challenge to factual findings in respect of injury; weight of evidence; assessment of evidence; failure to comply with Practice Direction No 6.................................................. 21 Parallel Lines Design Construction Pty Ltd v Bevins [2014] NSWWCCPD 46 .............. 25 Challenge to factual findings founded upon findings as to credibility of witnesses; procedural fairness.......................................................................................................... 25 2 Inghams Enterprises Pty Ltd v Sok [2014] NSWCA 217 WORKERS' COMPENSATION - appeal to Deputy President - errors of fact alleged against arbitrator - appeal limited to any error of fact, law or discretion - whether Deputy President failed to exercise appellate jurisdiction by restricting inquiry to errors of law - whether Deputy President failed to engage with the evidence to determine whether there were any errors of fact – 1998 Act, s 352 WORKERS' COMPENSATION - jurisdiction of Workers Compensation Commission dispute over liability for weekly payments of compensation - no determination of a dispute over a "work capacity decision" by an insurer permitted - decision by insurer to dispute liability not a "work capacity decision" - whether jurisdiction excluded over matters which fall within the description of a "work capacity decision" - effect of transitional provisions – 1987 Act, ss 43, 44, Sch 6 Pt 19H cl 3, cl 14 - 2010 Regulation Sch 8 cl 3 Court of Appeal 7 July 2014 Facts: The worker alleged that she received injury to her lumbar spine in the course of her employment with Integrated Parramatta Services Pty Ltd (Integrated) and Inghams Enterprises Pty Ltd (Inghams). The worker was employed by Integrated to perform work at Inghams’ premises between mid-2001 and November 2002. On 18 November 2002, the worker commenced employment at the same premises with Inghams. It was alleged against Integrated that a frank injury occurred on 21 October 2002 and further injury occurred due to arduous duties performed between 21 October 2002 and 17 November 2002. The allegation of injury against Inghams was, as a result of the nature and conditions of employment between 18 November 2002 and 15 June 2004, the worker received injury to her lumbar spine, with her employment terminated on 15 June 2004. The worker remained unemployed until she commenced work at Dick Smith Enterprises, a position arranged by Integrated, performing light duties in September 2004. Up until then she had been paid weekly compensation by Integrated. Employment at Dick Smith Enterprises ended in February 2005. The worker did not receive any further weekly payments from Integrated or its insurer. In June 2005, a lump sum compensation claim brought by the worker against Integrated was the subject of agreement, and payment was made in the sum of $10,000 in respect of eight per cent whole person impairment pursuant to s 66 of the 1987 Act. The worker was unemployed until 2007 when her husband purchased a takeaway food business. The business was conducted by the worker’s family between May 2007 and December 2010. The worker assisted for four or five hours per day, five days per week. Following the sale of the business, the worker remained unemployed. The worker continued to experience pain and disability in her lower back and her left leg. In May 2011, the worker was examined by Dr Charles H New, orthopaedic and spinal surgeon. In February 2012, Dr New recommended that the worker undergo surgical treatment being left L4/5 and L5/S1 decompression, laminotomy and neurolysis. Liability in respect of the cost of such treatment was declined by Integrated. 3 Claims in respect of weekly payments of compensation and the expenses to be incurred in respect of the surgery proposed by Dr New were declined by both Integrated and Inghams. A Commission Arbitrator upheld the worker’s claim and apportioned liability equally between Integrated and Inghams. Inghams and Integrated appealed to a Deputy President of the Commission under s 352 of the 1998 Act, which provides that the subject matter of an appeal is limited to a determination of any error of fact, law or discretion and that the appeal does not constitute a review or new hearing. The challenge before the Deputy President was initially confined to the factual findings made by the Arbitrator regarding the nature of the worker’s injury. A further challenge was made to the jurisdiction of the Commission to award weekly compensation payments after 1 January 2013. The basis for this challenge was that s 43 of the 1987 Act, which had effect under a transitional regulation from 1 January 2013, precluded the Commission from determining a dispute about weekly compensation payments when payments were subject to a work capacity decision. While no work capacity decision had been made, it was argued the prohibition in s 43 extended to matters that could be the subject of a work capacity decision. The Deputy President, dismissing the appeal, held that the challenge to the findings of fact demonstrated no relevant error and that, in the absence of a work capacity decision, s 43 was not an obstacle to the Commission rewarding weekly payments after 1 January 2013. The issues in dispute on appeal before the Court of Appeal were: (a) whether the Deputy President failed to exercise his appellate function by misconceiving it as being limited to errors of law and by failing to determine whether any of the errors of fact alleged should be accepted, and (b) whether the proper interpretation of s 43 precluded the Commission from determining, after 1 January 2013, matters that could be subject to a work capacity decision. Held: Appeal dismissed. Basten JA (Barrett JA and Sackville AJA agreeing) Whether the Deputy President erred in limiting the appeal to errors of law and failing to determine whether any of the errors of fact alleged should be accepted 1. Whilst the distinction between error of law and error of fact is accepted, the boundary is by no means easy to establish in any particular circumstances. Thus, whilst it is convenient to say that assessment of the weight of evidence did not raise a question of law, whereas an allegation of "no evidence" did, to classify specific reasoning by reference to that distinction is a fallible process [23]. 2. The proper conclusion was that identification of error by the Deputy President in the exercise of his appellate function must depend upon a consideration of his reasons taken as a whole, and not be limited to the use of particular words or phrases. Errors of approach are not identified by reference to linguistic niceties, particularly where the language used had no precise meaning [27]. 3. The requirement that a decision-maker give reasons is based on the need for a person affected to understand how a particular conclusion was reached. The reasons given may be persuasive or they may reveal error. For the appellate body to have said that 4 the reasons are persuasive or demonstrate no error may be sufficient to establish, at least on one basis, that there was no legal or factual error. For an appellate judge simply to adopt the reasoning of the first instance decision-maker may indicate a failure to address adequately the grounds of appeal. So long as that does not happen, there would be no necessary error in an appellate body accepting the reasons of the first instance decision-maker as a basis for dismissing a claim of factual error [28]. 4. The exercise necessary to establish that the Deputy President neither misunderstood his function, nor failed to carry it out, required reference to a number of further aspects of his reasons. It was not necessary to be comprehensive with respect to each ground of appeal, nor to repeat the process with respect to all grounds, as there was significant overlap [29]. 5. Once language used by the Deputy President was placed in context (both legal and factual) in the reasons, the submission that the Deputy President failed to understand his proper function or to exercise it to its full extent had to be rejected [42]. (ii) Whether the proper interpretation of s 43 precluded the Commission from determining, after 1 January 2013, matters that could be subject to a work capacity decision 6. The amendments to the Act came into operation on 1 October 2012. The operation of those amendments is regulated, in part, by transitional provisions found in Sch 6 Pt 19H cl 3(1) and (2). Those provisions were varied by the 2010 Regulation, Sch 8 cl 3(1) [44]. 7. It was argued that error had been made in holding that the Commission has jurisdiction to determine a dispute about matters that are properly the subject of a ‘work capacity decision’ within the meaning of s 43 of the 1987 Act in respect of the worker’s entitlement to weekly benefits from 1 January 2013. Error in making orders for payment of weekly benefits beyond 1 January 2013 was asserted [45]. 8. It was found that the relevant provisions for a determination of this question were not the transitional provisions but rather the substantive provisions as amended [48]. 9. Submissions put on behalf of the WorkCover Authority, which had intervened in the proceedings, were accepted and it was found that s 43 of the 1987 Act does not exclude jurisdiction with respect to matters that could be, but had not been, the subject of a work capacity decision. The Commission did not exceed its jurisdiction in making orders as to weekly payments after 1 January 2013 [54]–[58]. 5 Hills v Pioneer Studios Pty Limited (No 2) [2014] NSWWCCPD 42 Section 4 of the 1987 Act; injury arising out of or in the course of employment; injury received during interval between discrete periods of work; employer’s inducement or encouragement of worker to be at a particular place during such interval; injury received at that place and by reference to that place; employment caused or to some material extent contributed to injury; injury arose out of and in the course of employment; s 9A of the 1987 Act; employment a substantial contributing factor to injury O’Grady DP 10 July 2014 Facts: This appeal came before the Commission pursuant to an order of remitter made by the Court of Appeal on 26 September 2012. These proceedings were instituted in the Commission by Ms Kathryn Hills in August 2010. Ms Hills claimed medical expenses and lump sum compensation. The respondent to the application, Pioneer Studios Pty Limited (the respondent), Ms Hills’ former employer, had at first paid compensation benefits but had subsequently disputed Ms Hills’ entitlement to such benefits, following receipt by her of serious head and brain injuries in the early hours of the morning of 14 March 2004. Ms Hills had fallen over a balustrade at the respondent’s premises where she was attending a party which had commenced on the night of 13 March 2004. The respondent denied that the injury was a compensable injury in terms of ss 4, 9 and 9A of the 1987 Act. The Application came before a Senior Arbitrator for arbitration on 10 December 2010. On 13 January 2011, a Certificate of Determination, accompanied by reasons, was issued. An award in favour of the respondent was entered. Ms Hills brought an appeal against the Senior Arbitrator’s decision as permitted by s 352 of the 1998 Act, as it stood before operation of the 2011 amendments made to relevant legislation. Deputy President Roche delivered his decision on 1 June 2011. An order was made that the Senior Arbitrator’s determination be revoked. That order followed findings by the Deputy President that the subject injury arose out of Ms Hills’ employment and her employment was a substantial contributing factor to the injury. The respondent brought an appeal against the Deputy President’s decision pursuant to s 353 of the 1998 Act. The appeal was heard by the Court of Appeal on 26 September 2012. That appeal was upheld and the Court delivered its reasons extempore on that day. Ms Hills subsequently made application to the High Court of Australia seeking special leave to appeal against the whole of the judgment of the Court of Appeal. That Application was refused by the High Court on 2 April 2014 (Hayne and Crennan JJ). In accordance with the order made by the Court of Appeal, this matter then came before the Commission for consideration according to law. A preliminary telephone conference was conducted on 9 May 2014 at which time each party was represented. The reasons stated by the Court of Appeal were the subject of consideration and discussion at that conference. Mr Gross QC, appearing on behalf of Ms Hills, advised the Commission that, having regard to the reasons stated by the Court of Appeal, it was proposed to argue on the present appeal that the injury received by Ms Hills was one which had arisen in the course of her 6 employment in terms of s 4 of the 1987 Act. That argument had not been advanced before the Senior Arbitrator. The allegation made at that time had been expressly limited to an allegation that the injury had arisen out of Ms Hills’ employment within the meaning of that last mentioned section. No objection to Ms Hills’ proposal to raise a new argument on appeal was taken by Mr Silva, solicitor for the respondent. The grounds of appeal raised by the appellant contended that the Senior Arbitrator erred: (a) by applying the wrong test, namely the test concerning the question as to whether the injury arose in the course of employment, when determining whether the injury arose out of Ms Hills’ employment; (b) in failing to address submissions put by Ms Hills that Ms Martel: (i) had actual and ostensible authority on behalf of the respondent to encourage Ms Hills to attend the party for work purposes, and (ii) did exercise that authority by encouraging Ms Hills to attend the party. (iii) in her “consideration of the evidence and misapprehending the effect of the whole of the evidence”. Error is alleged in respect of suggested misapprehension of evidence given by Ms Martel including suggested concessions made by that witness in cross examination. (iv) in her apparent conclusion that Ms Hills’ employment was not a substantial contributing factor to her injury, and (v) in failing to find that the injury arose out of and in the course of employment and that Ms Hills’ claim is not defeated by s 9A. Held: The decision of the Senior Arbitrator and orders made as found in the Certificate of Determination dated 13 January 2011 were revoked. The injury received by Ms Hills on 14 March 2004 was found to be an injury within the meaning of s 4 of the 1987 Act and the respondent was ordered to pay Ms Hills’ reasonably necessary hospital and medical expenses under s 60 of the 1987 Act. Did Ms Hills’ injury arise in the course of her employment? 1. The High Court in Hatzimanolis v ANI Corporation Ltd [1992] HCA 21; (1992) 173 CLR 473 (Hatzimanolis) and Comcare v PVYW [2013] HCA 41; 303 ALR 1 (PVYW) were concerned with injury occurring during an interval or interlude in an overall period of work. The facts here concerned injury received at the respondent’s premises during an interval between discreet periods of work. Notwithstanding that distinction, the injury here may have occurred in the course of employment if it was established that the respondent expressly or impliedly induced or encouraged Ms Hills to spend that interval at a particular place, or in a particular way. Whilst it was stated in Hatzimanolis that “an injury is more readily seen as occurring in the course of employment when it has been sustained in an interval or interlude occurring within an overall period or episode of work, than when it has been sustained in the interval between two discreet periods of work”, the occurrence of compensable injury may nonetheless be found as having occurred in the latter circumstance [70]. 2. Ms Hills’ evidence was not specific concerning the identity of the person who informed her of the farewell party at the business premises and that it would be good if she attended the party. Whilst the evidence of Ms Hills failed to establish on the balance of probabilities that Mr Ludbrook, sole director and manager of the respondent, had spoken to Ms Hills in these terms, the probability was that Mr Ludbrook had enquired of her as to whether she was going to attend the farewell party, and the Deputy President found accordingly [74]. 7 3. The Deputy President reached the view that, on the probabilities, not only was Ms Hills spoken to with regard to attending the party, but that it was Ms Martel who spoke to her as described. Ms Hills’ inability to be more precise about the identity of the individual, that is, that it was either Mr Ludbrook or Ms Martel, may be explained having regard to the neurological effects of her injury upon her memory [79]. 4. The exchanges that took place between Ms Martel and Ms Hills also constituted relevant inducement or encouragement to attend the party. It was correct, as argued, that Ms Martel’s evidence in cross-examination suggested she had limited “authority”, however the actual and implied authority with which Ms Martel was invested must be assessed having regard to Mr Ludbrook’s evidence of “stepping back” and delegating the training of Ms Hills to his staff. It was plain on the evidence that it was Ms Martel who assumed the role of trainer and supervisor. The evidence accepted by the Deputy President was that Ms Martel spoke to Ms Hills about attendance at a “farewell party here for [Mr Buchanan, a fellow employee] on Saturday night”. Having regard to her role as supervisor and the fact that the party was described by her in terms similar to those used by Mr Ludbrook, that is, as a “farewell”, the Deputy President concluded that Ms Martel was acting within her actual or implied authority granted by Mr Ludbrook in so inducing or encouraging Ms Hills’ attendance [87]. 5. The relevant circumstances of Ms Hills’ injury were that: (a) it occurred during an interval between periods of employment; (b) the respondent, through Mr Ludbrook and Ms Martel, had encouraged or induced Ms Hills to be present during that interval at a particular place, namely the business premises in Broadway Sydney; (c) a purpose of Ms Hills’ presence was employment related, being a farewell party for a fellow employee; (d) the “factual association or connection” with Ms Hills’ employment, which matter is considered in PVYW, concerned the respondent’s inducement or encouragement to be at that place, and (e) the injury was received at the place (the business premises) and by reference to that place (Ms Hills fell on the stairs) [88]. 6. The matters enumerated above established that the subject injury was suffered at and by reference to a place where the respondent had induced or encouraged Ms Hills to be (PVYW). The respondent did not place reliance upon any argument as to misconduct in terms of s 14 of the 1987 Act. The Deputy President found on review that the subject injury was received in the course of Ms Hills’ employment [89]. 7. Where an injury occurs in the course of employment, it will almost invariably be found to have arisen out of that employment. Such was the case in the present circumstances. Ms Hills’ presence at the party came about by reason of the matters earlier discussed and concerned her participation in a farewell of a fellow worker. Her unchallenged evidence was that she knew nothing concerning any other purpose for the holding of the party other than that farewell. The evidence suggested no reason other than employment related reasons for her presence upon the premises at the time of injury. In such circumstances the employment caused or to some material extent contributed to the subject injury. Having regard to that fact and to the decision in Nunan v Cockatoo Docks and Engineering Co Pty Ltd [1941] NSWStRp 23, the Deputy President found that the subject injury, being causally related to her 8 employment, arose out of that employment within the meaning of s 4 of the 1987 Act [90]. 8. Ms Hills argued that the requirements of s 9A of the 1987 Act were satisfied and her submissions on this appeal adopted the reasoning expressed by Roche DP in his earlier decision in this matter. Whilst one must immediately acknowledge that the Deputy President’s findings and orders were set aside by the Court of Appeal, it should be noted that the reasoning of the Court drew attention to the need to consider the matters raised by s 9A by reference to the decision of Mercer v ANZ Banking Group Ltd [2000] NSWCA 138; (2000) 48 NSWLR 740 [91]. 9. What Ms Hills was doing in her employment as discussed earlier was causally related to her injury, and the strength of such causal linkage was real and of substance. In reaching that conclusion, the Deputy President took into account and adopted the reasoning of Roche DP in Hills v Pioneer Studios Pty Ltd [2011] NSWWCCPD 30 concerning matters raised by s 9A(2). The Deputy President, in the present appeal on remitter, found that Ms Hills’ employment was a substantial contributing factor to the injury [92]. 9 Trustees of the Society of St Vincent de Paul (NSW) v Maxwell James Kear as administrator of the estate of Anthony John Kear [2014] NSWWCCPD 47 Subarachnoid haemorrhage suffered at work after “near miss” riding a motor scooter to work; whether worker received a personal injury on a journey to which s 10 of the 1987 Act applies; meaning of “personal injury”; whether “shock” is a personal injury; whether elevated blood pressure is a personal injury; absence of evidence Roche DP 28 July 2014 Facts: On 8 February 2009, the worker, Anthony Kear, was riding his Vespa motor scooter to the Matthew Talbot Hostel, his place of employment with the respondent, when a car suddenly pulled out in front of him. Though he avoided a collision, and did not fall from his scooter, he said that he was in a state of shock, very upset and thought that he may have been killed. For convenience, this incident was referred to as “the near miss”. The worker continued on his journey to work, where he was rostered to work the night shift at 10 pm. Shortly after arriving at about 10 pm, his boss noticed the worker was upset and called him into his office. Though the worker had no further recollection, it was accepted he collapsed in the office and was taken by ambulance to hospital. It was accepted that the worker suffered an aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage (the haemorrhage) at work on the evening of 8 February 2009. It was not argued that the haemorrhage occurred while the worker was on his journey to work. Both the worker’s supervisor, Brett Macklin, and one of his colleagues, Anne Brown, were witnesses. The accident report form dated 9 February 2009, completed by Mr Macklin, described the events at work on 8 February 2009 as follows: “Came to work after nearly being hit by a car, he was (appeared to be in shock)[.] He became faint and fell and became unconscious.” Under “Details of Incident” the time “2130” is recorded. It appeared it was assumed that this was the time when the worker collapsed, rather than the time of the near miss. The worker claimed lump sum compensation of $35,750 in respect of a 22 per cent whole person impairment for impairments that resulted from the haemorrhage, plus $33,000 for pain and suffering. The appellant’s insurer disputed liability on various grounds, most misconceived. The appellant did not dispute that, at the time of the near miss, the worker was on a daily or other periodic journey between his abode and place of employment (s 10(3)(a)) but whether he received a personal injury on the journey. The worker died on 3 June 2013. His brother, Maxwell Kear, as administrator of his estate, was substituted as the applicant under Pt 18 r 18.4 of the 2011 Rules. It was agreed at the arbitration that, to establish that he had received a personal injury on a journey, the worker had to establish that he suffered a sudden identifiable pathological change on his journey to work (North Coast Area Health Service v Felstead [2011] NSWWCCPD 51 (Felstead), applying Kennedy Cleaning Services Pty Ltd v Petkoska [2000] HCA 45; 200 CLR 286 (Petkoska)). 10 The Arbitrator delivered an extempore decision, finding that the worker established that he suffered a personal injury because he suffered shock and upset causing an elevation in his blood pressure, which satisfied the test of a sudden identifiable pathological change. The appellant challenged the Arbitrator’s finding that the worker received a personal injury on a journey to work on 8 February 2009. The issues in dispute in the appeal were whether the Arbitrator erred in: (a) finding that the worker suffered a personal injury on a journey to which s 10(1) applies in the form of “a medical condition of shock”; (b) determining that the evidence permitted a finding that the worker’s blood pressure was raised following the near miss, and (c) finding that the worker suffered a personal injury because of the “considerably elevated blood pressure as shown in the clinical notes”. Held: The appeal was successful. The worker did not receive a personal injury on a journey to which s 10 of the 1987 Act applies. Discussion and findings 1. A “personal injury” is “a sudden and ascertainable or dramatic physiological change or disturbance of the normal physiological state” (Petkoska). That is “a sudden identifiable pathological change” (Felstead). While the Arbitrator purported to apply that test, his conclusion was not open on the evidence [38]. 2. The nature of a personal injury is well illustrated in the authorities, where the following have been held to be personal injuries: a sudden rupture of blood vessels and consequent cerebral haemorrhage arising from a congenital weakness (Accident Compensation Commission v McIntosh [1991] VicRp 65); a coronary occlusion caused by a piece of lining of an artery having loosened (Hume Steel Ltd v Peart [1947] HCA 34; (Peart)); the rupture of an aneurysm (Clover, Clayton & Co Ltd v Hughes (1910) AC 242), and the rupture of the oesophagus (held to be a personal injury by accident) (Kavanagh v The Commonwealth [1960] HCA 25) [39]. 3. Consistent with these authorities, where the alleged condition is “shock”, for a worker to have received a personal injury, it is necessary that the event or events complained of had a physiological effect, not a mere emotional impulse (Yates v South Kirkby Collieries Ltd [1910] 2 KB 538; Anderson Meat Packing Co Pty Ltd v Giacomantonio [1973] 47 WCR 3; Thazine-Aye v WorkCover Authority (NSW) (1995) 12 NSWCCR 304; Zinc Corporation Ltd v Scarce (1995) 12 NSWCCR 566). Whether a worker has suffered a physiological effect will depend on the nature and severity of symptoms [40]. 3. There was no evidence that established that the worker received a personal injury, in the sense of a sudden and ascertainable or dramatic physiological change, on his journey to work on 8 February 2009. As “shock” is a medical diagnosis, it was appropriate to consider expert evidence before making such a diagnosis. There was no such expert or lay evidence from which to infer such a condition [41]. 4. There was no evidence explaining what it was about the worker’s appearance that led Mr Macklin and Ms Brown to conclude that he was in shock. As their observations were made immediately before the worker collapsed, it was possible that, rather than describing “shock”, they were describing the early effects of the subarachnoid haemorrhage. In any event, there was no evidence that Mr Macklin or Ms Brown had 11 any medical qualifications or training. Their opinions did not support a finding that the worker suffered “shock”, in the medical sense, on his journey to work [43]. 5. The evidence of Professor Fearnside, neurological surgeon qualified on behalf of the worker, addressing whether the haemorrhage resulted from the near miss, did not support the Arbitrator’s conclusion that the worker suffered a personal injury of shock. The only physiological event that satisfied the test of a personal injury in the present case was the subarachnoid haemorrhage which occurred at work, not “on” a journey. It followed that, if the “shock” was not a personal injury, and as there was no evidence that it was, the Arbitrator’s decision could not stand [46]. 6. The Arbitrator approached the issue on a completely wrong basis. He said that the overall impression was that the claim form was completed almost contemporaneously with the event in question. There were two problems with this statement. First, as the claim form was dated 9 February 2009, the day after the worker collapsed, it could not be described having been completed almost contemporaneously. Second, the Arbitrator’s statement suggested that he thought the “event in question” was the collapse. The “event in question” was the near miss that occurred when the worker was riding from his home to his place of employment. The issue was whether the worker received a personal injury on that journey [52]. 7. There were a number of difficulties with the Arbitrator’s statements that he believed the test of whether the worker had received a personal injury was satisfied and that he was easily persuaded that the worker suffered shock and upset causing an elevation in his blood pressure and that satisfied the test of a sudden identifiable pathological change [53]–[55]. 8. First, the worker’s description of the events was particularly brief and consisted only of him saying that he was in a state of shock, that he was very upset and that he thought he could have been killed. There was nothing in that description that supported a finding that the worker received a personal injury on the journey [56]. 9. Second, the history of considerably elevated blood pressure in the clinical notes only established the worker had high blood pressure, both before and after the near miss. It did not establish that the near miss caused an increase in his blood pressure. Professor Fearnside merely said that if the experience was sufficient to raise the worker’s blood pressure, raised blood pressure can be a causal factor in a subarachnoid haemorrhage. Similarly, Professor Kiernan, neurologist qualified by the appellant, noted that an aneurysm may burst due to high blood pressure. Neither statement supported the Arbitrator’s conclusions [57]–[58]. 10. Given the limited evidence tendered before the Arbitrator, this was not a case in which the Commission could infer that, because of a stressful event, there had been an increase in blood pressure. In any event, the authorities did not support the proposition that, on its own, an elevation in blood pressure is a personal injury [59]. 11. Third, neither the worker’s “state”, as recorded in the form, nor Ms Brown’s description, established that the worker received a personal injury on a journey [62]. 12. Last, there was no basis for the Arbitrator’s statement that the worker’s condition went “well beyond the general terms of shock and upset” [63]. 12 Rodger W Harrison and Peter L Siepen t/as Harrison and Siepen v Craig [2014] NSWWCCPD 48 Drawing of inferences on injury in the absence of expert medical evidence; judicial obligation to make findings of fact on proved evidence; circumstances in which the Commission’s members may rely on general knowledge acquired in their capacity as members of a specialist tribunal; interlocutory decisions Keating P 29 July 2014 Facts: The worker was employed by the appellant as an office assistant. On 8 June 2004, whilst descending a staircase at the appellant’s premises, the worker slipped and fell, landing on her tailbone and left leg. She also injured her right arm. The worker was unfit for work for two days. In early 2006, the worker trained to become an assistant in nursing (AIN). On 20 November 2006, the worker obtained employment as an AIN at a retirement village. After working only three shifts she developed severe pain in her lower back and shooting pain in her left leg and as a result ceased work, never returning again to that type of employment. On 20 October 2009, the worker made a claim for lump sum compensation for five per cent whole person impairment with respect to the lumbosacral spine. That claim was denied by the appellant’s insurer. The insurer alleged that at the time of the injury on 8 June 2004, the worker reported injuries to her sacral/coccygeal area and the right forearm. It was alleged that it was not until November 2006 that the worker complained of pain in her lower back. Further, it was alleged that any injury to the lower back was the result of the work in 2006 as an AIN. On 8 February 2013, the worker lodged an Application to Resolve a Dispute in the Commission. She claimed lump sum compensation in respect of the injury to her “lumbar spine” on 8 June 2004. On 1 April 2014, a Commission Arbitrator found that the worker suffered an injury to her lumbar spine on 8 June 2004 arising out of or in the course of her employment with the appellants, or, to which the employment was a substantial contributing factor. He ordered that the matter be referred to the Registrar for referral to an AMS in respect of an assessment of the worker’s whole person impairment relating to the injury to the lumbar spine. The issue in dispute on appeal was whether the Arbitrator erred in finding that the worker injured her lumbar spine when there was no sound evidentiary basis for the finding and/or it was against the weight of the evidence. (It was alleged that the symptoms experienced by the worker were referable either to a subsequent event or the underlying degenerative processes.) Held: Leave to appeal was granted. The Arbitrator’s orders were revoked and an award was entered for the employers. 13 Interlocutory Decision 1. The Arbitrator’s referral of the matter to the Registrar for referral to an AMS does not finally dispose of the rights of the parties and is interlocutory: Licul v Corney [1976] HCA 6; 180 CLR 213; 8 ALR 437 [18]. 2. If leave to appeal was permitted and the appeal was successful, that would finally determine the issue between the parties and it would obviate the necessity of an assessment by an AMS and unnecessary utilisation of the Commission’s resources. For those reasons it was desirable for the proper and effective determination of the dispute that leave to appeal be granted (s 352(3A) of the 1998 Act) [19]–[21]. Discussion and Findings 3. The Arbitrator’s conclusion that the worker’s disc pathology at L4/5 was unrelated to the fall in 2004 was, for the reasons expressed by the Arbitrator, correct and was not challenged on appeal [72]. 4. Following that finding, the Arbitrator considered whether the developmental abnormality (“pseudoarthrosis”) referred to in the 2004 radiology was aggravated by the injury in 2004. Without the assistance of any expert medical evidence on that point, the Arbitrator concluded, by way of inference, that the pseudoarthrosis was aggravated by the injury in 2004. That finding was not open to the Arbitrator on the available evidence, was contrary to the evidence and constituted an error [73]–[74]. 5. Neither of the specialist doctors specifically addressed the question of whether the worker suffered from an aggravation of the congenital pseudoarthrosis as a result of the 2004 injury [75]. 6. The Arbitrator appeared to be stating that, notwithstanding an absence of specific medical evidence on the question of aggravation, the Commission may rely upon on its own medial expertise to draw medical inferences (Belmont Night Patrol Pty Ltd v Woolworths Ltd [2004] NSWCA 235 (Belmont)). He noted however that there must be some evidence to support the inference (Hevi Lift (PNG) Ltd v Etherington [2005] NSWCA 42) [76]. 7. The Arbitrator identified the basis for his inference as follows: (a) the worker suffered a significant fall on her buttocks involving her full weight with consequent forces being applied from the point of contact (tailbone) upward throughout her body; (b) the effect was sufficient for her to attend her general practitioner and complain of pain in the sacrum; (c) x-rays revealed evidence of the congenital pseudoarthrosis, and (d) the histories provided by the specialist doctors included a complaint of pain in the buttocks, in addition to the coccyx symptoms [77]. 8. Based on those facts, the Arbitrator concluded that the symptoms were consistent with an aggravation of the early “degenerative change” to a person so young. The worker was 18 years of age in June 2004 [78]. 14 9. It is a fundamental judicial obligation to make findings of fact on proved evidence (not being matters of common knowledge or judicial knowledge (Strinic v Singh [2009] NSWCA 15)). Even if a judge is experienced in adjudicating in medical matters “that experience does not replace the requirement to base findings on the evidence” (at [64]). A party is not afforded procedural fairness where a trial judge makes a finding of fact based on the judge’s own purported knowledge, or understanding of matters that do not form part of the evidence [79]. 10. It may be open to an Arbitrator to make a finding of causation and/or injury by inference supported by appropriate lay and/or expert evidence. However, it is not open to an Arbitrator to make a finding that is inconsistent with the lay evidence and is unsupported by expert medical opinion [85]. 11. The worker’s submissions depended upon an acceptance of the proposition that an Arbitrator may make a finding of injury without specific medical evidence based on the Commission’s knowledge as a specialist tribunal and may draw inferences based on evidence, relying on the authority in Belmont (in considering MMI Workers Compensation (NSW) v Kennedy [1993] NSWCC26; [1993] NSWCC 26; 9 NSWCCR 482 (Kennedy)). However, the respondent was unable to draw any assistance from that authority [86]. 12. The facts in Kennedy were distinguished. First, not only was there no evidence that the worker in the present case suffered pain in her lumbar spine as a result of the incident in 2004, her evidence was to the contrary. The worker only complained of some discomfort in her tailbone to the general practitioner following the injury on 8 June 2004. Secondly, on close questioning by one of the specialist doctors, the worker denied having suffered any pain in her lower back between 2004 and 2006. Thirdly, the history obtained by another general practitioner suggested that the worker attributed the pain in her low back and leg to a fall in 2006 [89]. 13. It followed that the Arbitrator’s inferential finding of aggravation of a congenital condition, in the absence of expert medical evidence, involved an error of law [91]. 15 Boral Recycling Pty Ltd v Figueira [2014] NSWWCCPD 41 Finding of no current work capacity; weight of evidence; relevance of worker’s applications for full-time employment; assessment of medical evidence; s 32A of the 1987 Act; application of principles in Hancock v East Coast Timber Products Pty Ltd [2011] NSWCA 11; 80 NSWLR 43; alleged failure to give reasons Roche DP 4 July 2014 Facts: The respondent worker worked for the appellant employer, Boral Recycling Pty Ltd (Boral), as a personal assistant from January 2010 until being made redundant on 28 February 2013. She stopped work, due to her injury, on 8 December 2012. She had previously worked for one of Boral’s related companies between 2003 and 2010. The worker alleged that she suffered a psychological injury as a result of having been harassed, criticised and victimised by her managers and work colleagues from August 2010 until February 2013. By letter dated 31 October 2012, the worker notified Boral’s insurer, QBE Workers Compensation (NSW) Ltd (QBE), of her claim for compensation and gave a date of injury of 8 October 2012. QBE disputed liability for the claim. The worker claimed weekly compensation from 15 October 2012 to 26 October 2012, from 9 December to date and continuing and a general order for the payment of hospital and medical expenses, as a result of her psychiatric injury. At arbitration, Boral disputed injury, whether employment was the main contributing factor to any disease injury, whether the injury had been wholly or predominantly caused by reasonable action with respect to performance appraisal, incapacity, entitlement to hospital and medical expenses and the Commission’s jurisdiction to determine a claim for weekly compensation in accordance with the 1987 Act as amended by the Workers Compensation Legislation Amendment Act 2012. In respect of the claim for weekly compensation beyond 1 March 2013, Boral argued that, as the worker made numerous applications for full-time employment between March and July 2013 for work similar to her pre-injury employment with Boral, she had no incapacity from that time. The Arbitrator found against Boral on all issues. He found that the worker suffered from a Major Depressive Disorder and/or Adjustment Disorder, a disease, which she contracted in the course of her employment and to which her employment was the main contributing factor. Dealing with the period from 1 March 2013, the Arbitrator said that the worker’s job applications did not necessarily mean she considered herself fit for that work. The Arbitrator found, relying on evidence from her general practitioner, Dr Gunawardena, and other evidence, that the worker had no current work capacity from 15 October 2012 to 26 October 2012 and 9 December 2012 to 30 June 2013. He found that from 1 July 2013, she was fit to work in suitable employment for 21 hours per week earning $630. The issues in dispute on appeal were whether the Arbitrator erred in: (a) determining that the job applications the worker made from March 2013 did not necessarily mean that she considered she was fit to perform the jobs for which she applied and in giving insufficient weight to those applications, and 16 (b) relying on the certificates of capacity from the worker's general practitioner, Dr Gunawardena, as being a satisfactory basis on which to determine her capacity for work and in placing undue weight on certification of work capacity in the certificates. Held: The Arbitrator’s determination of 10 March 2014 was confirmed. Discussion and findings 10. As the worker did not directly address her fitness for work in her statements, the submission that, in her view, she was fit for full-time work was an inference from her having made several job applications in the period concerned. That inference may or may not have been correct. In his report of 25 November 2013, Dr Roberts, the psychiatrist qualified by QBE, stated that the worker would need to discuss with her doctor if she were offered a full-time position. That history supported the conclusion that the worker clearly did not think she was fit for full-time work without first checking with her doctor. Her doctor was of the view that she was not fit for such work, or, in the period up to 30 June 2013, fit for part-time work [37]. 11. Even if it were accepted that the worker thought she was fit for full-time work, and as the Arbitrator (correctly) did not believe that that was her view, that would not have been determinative. First, a worker’s subjective view of fitness for work will not normally be determinative, especially in a case involving a psychological injury, and the Arbitrator was not bound to accept the job applications as evidence of a capacity to work. He had to consider the whole of the evidence, including the medical evidence, and make an assessment based on that evidence, which was what he did [38]. 12. Second, at its highest, the worker’s alleged view of her capacity was no more than an informal out-of-court admission or concession that may be contradicted by other evidence. As held in Damberg v Damberg [2001] NSWCA 87; 52 NSWLR 492, a court (or tribunal) can choose between the admission and the other evidence and is not bound to accept the admission as correct, even if it is not contradicted. In the present case, the worker’s admission was contradicted by a substantial body of medical evidence, which the Arbitrator considered in reaching his conclusion. He therefore did not err in not accepting the worker’s alleged admission [39]. 13. The appellant relied on the observation in Jackson v Cement Australia (Kandos) Ltd [2012] NSWWCCPD 67 (Jackson) that the worker’s efforts to obtain work as a receptionist strongly suggested it was not her view that, despite her injury, such work was beyond her. The medical evidence, and the worker’s evidence that she had been looking for suitable duties, provided evidence that it was not her view that she was totally unfit for work. It followed that, on the whole of the evidence in that case, the Arbitrator had not erred in not finding the worker to be totally unfit. There was no valid comparison between Jackson and the present claim. Contrary to Jackson, in this claim, the medical evidence in the period concerned was that the worker had no capacity for work. Contrary to the appellant’s submission, Jackson did not “demonstrate how the Arbitrator should have approached and considered the making of the job applications in the present matter”. It was decided on its own facts and provided no assistance at all in the present matter [41]–[42]. 14. Moreover, even if the worker had considered herself fit for those jobs, even part-time, her subjective view was not determinative but had to be weighed against the other evidence in the case, which included evidence of the nature of the injury, its consequences, and the medical evidence. The Arbitrator weighed the relevance of the job applications against the other evidence. That approach was appropriate [44]. 17 15. In assessing whether the worker had “no current work capacity” between 1 March 2013 and 30 June 2013, the Arbitrator had to consider if, arising from her injury, the worker was “not able to return to work, either in pre-injury employment or in suitable employment” (s 32A). Applying s 32A, the first matter to which the Arbitrator had to have regard was the nature of incapacity and details provided in medical information including, but not limited to, any certificate/s of capacity supplied by the worker. The certificates of capacity in the matter were from Dr Gunawardena [45]-[46]. 16. Given the medical evidence, save for Dr Roberts’s evidence, the appellant’s criticism of the Arbitrator for relying on Dr Gunawardena’s medical certificates was surprising. The Arbitrator was not only entitled to have regard to Dr Gunawardena’s certificates, he was required to do so [61]. 17. The submission that the Arbitrator should have placed little, if any, weight on Dr Gunawardena’s certificates, because there was no evidence he was aware the worker applied for positions similar to her pre-injury role, was unsustainable. That submission was not made at the arbitration; instead it was submitted that no weight could be given to the certificates because the doctor had not explained why the worker had no capacity prior to 1 August 2013 and was only fit for 21 hours per week thereafter, in light of the worker’s job search in that period. It is not an error for an Arbitrator not to deal with a point not argued (Brambles Industries Ltd v Bell [2010] NSWCA 162) [62]. 18. The second attack on the Arbitrator’s acceptance of Dr Gunawardena’s certificates was based on the Arbitrator’s alleged criticism of the doctor’s opinion on causation. That attack was baseless. The Arbitrator was not critical of Dr Gunawardena’s opinion on causation. He merely observed, quite properly, that it would have been prudent if the worker’s solicitors had obtained copies of the doctor’s clinical notes and a detailed report. The Arbitrator accepted Dr Gunawardena’s opinion on causation, which was supported by other evidence [64]–[65]. 19. When considered on the background of the evidence from Mr Jupp (the treating psychologist), Dr Henson (the treating psychiatrist) and Dr Canaris (the worker’s qualified psychiatrist), the acceptance of Dr Gunawardena’s evidence complied with the principles in Hancock v East Coast Timber Products Pty Ltd [2011] NSWCA 11; 80 NSWLR 43 and involved no error. If there were errors, they made no difference to the outcome because the full histories from the worker’s medical experts were even more supportive of her case on incapacity than the Arbitrator had allowed [80]. 20. The appellant’s submissions raised an additional ground of appeal, namely that the Arbitrator erred in failing to give reasons for his findings on incapacity. The complaint was without merit. A tribunal must give reasons for its decision, not the sub-set of reasons why it accepted or rejected individual prices of evidence (Re Minister for Immigration and Multicultural Affairs; ex parte Durairajasingham [2000] HCA 1; 74 ALJR 405; applied in Twynam Agricultural Group Pty Ltd v Williams [2012] NSWCA 326)) [84]. 21. The Arbitrator exposed his reasoning on the critical issue in dispute (the worker’s work capacity) and articulated the essential ground on which he based his decision (Soulemezis v Dudley (Holdings) Pty Ltd (1987) 10 NSWLR 247). That ground was based on his acceptance of Dr Gunawardena’s evidence, on a background of evidence from Mr Jupp and Drs Henson and Canaris, and the worker’s age, education, skills, work experience and the other matters in the definition of suitable employment. His reasons were adequate in the circumstances. 18 Iqbal v Hotel Operations Solutions Pty Ltd [2014] NSWWCCPD 45 Interlocutory orders; leave to appeal; dismissal of proceedings by Arbitrator for want of prosecution pursuant to s 354(7A)(c) of the 1998 Act; failure to comply with an Arbitrator’s directions; failure to properly particularise a claim for permanent impairment compensation Keating P 22 July 2014 Facts: The worker was employed by the respondent as a room attendant. His duties involved cleaning hotel rooms. He alleged that as a result of pushing, pulling and twisting of his body, whilst cleaning hotel rooms, he suffered a serious spinal injury and is incapacitated for work. The worker’s claim for weekly payments of compensation was denied by the respondent’s insurer. On 27 December 2012, the worker lodged in the Commission an Application to Resolve a Dispute (the Application) claiming weekly payments of compensation and lump sum compensation. On 13 September 2013, the matter was listed for a telephone conference before a Commission Arbitrator. The respondent sought to have the matter struck out on the basis that the evidence filed with the Application failed to support the claims made. The Arbitrator refused that application at that time and made a series of orders, which included an order that by 29 November 2013, the worker serve on the respondent a claim for permanent impairment benefits supported by appropriate medical evidence. The telephone conference scheduled for 31 January 2013 was rescheduled, to 20 March 2014, at the request of the worker to rectify deficiencies in the Application. The worker sought a further adjournment at the telephone conference listed on 20 March 2014. That application was refused. The Arbitrator found that the worker had failed to comply with the orders made on 13 September 2013, and that the matter was not in a fit state to proceed, and could not be made ready within 14 days. The Application was struck out for failure to prosecute the claim with due dispatch, pursuant to s 354(7A)(c) of the 1998 Act and r 15.8 of the 2011 Rules. Held: Leave to appeal was refused. Consideration 1. There was no dispute that the Arbitrator’s determination and orders appealed against were interlocutory and that leave to appeal was required pursuant to s 352(3A) of the 1998 Act [43]. 2. The President found that granting leave to appeal was neither necessary nor desirable for the proper and effective determination of the dispute. If leave to appeal were granted, the matter, which was clearly inadequately prepared, would simply be referred to another Arbitrator and would still not be in a position to proceed [44]. 19 3. The Arbitrator made no determination on the merits of the claim. The worker’s rights can be fully protected by filing a fresh application when the matter is in a fit state to proceed [45]. 4. Accordingly, leave to appeal was refused [46]. 5. Despite refusing to grant leave to appeal, the President made the following observations. The worker failed to provide proper particulars of his claim for permanent impairment compensation. In particular the purported claim for permanent impairment was not supported by a medical report completed in accordance with the “WorkCover Guidelines for Claiming Compensation Benefits” by a medical specialist with qualifications and training in the relevant body systems claimed [48]. 6. It appeared that the “amended claim for permanent impairment benefits” was prepared either by the worker or his solicitor based on an assessment of the worker’s entitlements from their own assessment of the evidence. That did not comply with the guidelines for claiming permanent impairment compensation and it was improper to attempt to support a claim for permanent impairment compensation in that way [49]. 7. It is not until the claim is properly particularised in accordance with the legislation and the guidelines that the respondent will be in a position to respond to the claim. This was the very issue that was central to the Arbitrator’s decision to strike the matter out [50]. 8. Because the worker had failed to comply with the requirements to make a valid claim for lump sum compensation, the respondent had not been given an opportunity to either deny liability or to make an offer of settlement. Therefore there was a question about whether a dispute had arisen and whether there was anything that can be referred to the Commission (Shams v Venue Services Group Pty Ltd [2013] NSWWCCPD 57) [51]. 20 Secretary, Department of Family and Community Services v Victoire [2014] NSWWCCPD 44 Challenge to factual findings in respect of injury; weight of evidence; assessment of evidence; failure to comply with Practice Direction No 6 Roche DP 22 July 2014 Facts: At the time of injury, the worker worked as a disability support worker at Cabramatta Respite, a centre for disabled persons suffering physical, intellectual and borderline psychiatric disabilities. On 28 February 2004, one of the clients absconded by jumping over a fence. The worker followed to direct him to return. The agitated client grabbed the worker’s left arm, twisted it, and pushed the worker back forcibly into a fence with at least two powerful impacts. The patient then let go and the worker escorted him back. The worker was in considerable pain and an ice pack was applied to his left shoulder. He attended Liverpool Hospital for treatment and was off work for three days. He saw his general practitioner, Dr Chung, who, because of ongoing symptoms, referred the worker for x-rays of his cervical spine and lower thoracic spine on 2 March 2004. On 1 June 2004, the same patient assaulted the worker again by grabbing his left arm and dragging him towards a wall while the worker was sitting on a chair. The worker felt an electric shock-like sensation into his left arm. By letter dated 15 June 2009, the worker claimed lump sum compensation of $17,000 with respect to a 13 per cent whole person impairment as a result of injuries to his cervical spine, thoracic spine and left shoulder on 28 February 2004 and 1 June 2004. The claim was supported by a report from Dr Patrick, orthopaedic surgeon, dated 21 April 2009, where he assessed the worker to have the following impairments due to the work incidents after deductions for pre-existing conditions: six per cent due to his cervical spine injury (seven per cent without deduction); four per cent due to his thoracic spine injury (five per cent without deduction), and three per cent due to the injury to his left upper extremity. The worker settled a claim on 25 September 2009 for lump sum compensation for the injury to his left upper extremity for $2,500, representing a two per cent whole person impairment. On 30 January 2013, the worker commenced proceedings in the Commission in which he claimed lump sum compensation of $13,000 ($15,500 less the $2,500 previously paid for the left upper extremity) in respect of a 12 per cent whole person impairment, plus $20,000 for pain and suffering. The 12 per cent was arrived at by combining the impairments for the cervical spine (seven per cent) and the thoracic spine (five per cent) without allowing for any pre-existing conditions. The appellant disputed liability on the ground that the worker did not injure his thoracic spine on either 28 February 2004 or 1 June 2004, it being conceded that he had injured his cervical spine on 28 February 2004. The Arbitrator found that the worker injured his thoracic spine on 28 February 2004. The Commission issued a Certificate of Determination on 25 March 2014 stating that the matter was to be remitted to the Registrar for referral to an AMS for assessment of permanent impairment as a result of injuries to the cervical spine and thoracic spine on 28 February 2004. 21 The appellant’s counsel asserted that the Arbitrator erred in finding that the worker injured his thoracic spine on 28 February 2004, because he: (a) failed to consider and place due weight on the relevant contemporaneous evidence and consequent medical evidence; (b) relied on an x-ray dated 2 March 2004 as evidence in support of the worker’s claim; (c) relied on a finding by Dr Dalton, the worker’s treating specialist, of symptoms in the worker’s thoracic spine as evidence in support of the claim; (d) found that, because the incident on 28 February 2004 was capable of causing injury to the cervical spine, it also caused injury to the thoracic spine, and (e) found that the mechanism of injury was capable of causing injury to the worker’s thoracic spine. Both parties incorrectly asserted that the appeal was not an appeal against interlocutory orders. Though the worker’s impairments had been assessed by an AMS, as the Commission had not made any formal orders finally determining the parties’ rights, the Arbitrator’s orders were interlocutory (Licul v Corney [1976] HCA 6; 180 CLR 213) and the appellant required leave to appeal (s 352(3A) of the 1998 Act). Held: Leave to appeal was granted. The Arbitrator’s determination was confirmed and the matter remitted to the same Arbitrator for determination of all outstanding issues. Discussion and findings Contemporaneous evidence 1. The Arbitrator was not bound to reject the claim, and did not err in not finding against the worker, because of a lack of contemporaneous complaint in the medical evidence, the claim form and the Incident Report form of an injury to the thoracic spine. The Arbitrator’s task was to decide, on the basis of the whole of the evidence, what evidence he or she accepts (Chanaa v Zarour [2011] NSWCA 199). The Arbitrator assessed the whole of the evidence and accepted the worker injured his thoracic spine on 28 February 2004. That finding was open to him and disclosed no error [28]. The March 2004 x-ray 2. The worker’s complaints clearly encompassed the lower thoracic spine, which is part of what a layperson would describe as the mid-back. It was therefore of no consequence that the x-ray was of the lower thoracic spine. The referral for the x-ray of the lower thoracic spine was a matter the Arbitrator was entitled to consider in his overall assessment of the claim. However, it was not determinative and the Arbitrator did not treat it as such. Thus, if the Arbitrator did err in relying on the x-ray of the lower thoracic spine, it made no difference to the result. The relevance of the submission that the x-ray did not reveal any injury was unclear. The worker never alleged that it did. He relied on the evidence of Dr Patrick, orthopaedic surgeon, which was that he suffered an “upper/mid thoracic facet injury” [32]–[33]. 22 Dr Dalton’s evidence 3. When read in its proper context, Dr Dalton’s failure to state expressly that the worker injured his thoracic spine on 28 February 2004, or that the stiffness in the thoracic spine was a result of that incident, was of no consequence. The doctor had a clear and consistent history of the incident and of continuing left-sided neck and shoulder girdle pain, and thoracic spine stiffness. In the absence of any other potential cause of that stiffness, the Arbitrator was entitled to rely on Dr Dalton’s evidence in his assessment of whether the worker injured his thoracic spine [40]. 4. When the whole of the evidence is considered, Dr Dalton’s failure to refer to pain in the thoracic spine was also of no consequence. Moreover, the submission that there was no evidence of pain in that area was incorrect. The evidence of pain in the thoracic spine was found in the evidence from the worker’s treating psychologist, Stephen Whyte, and in the worker’s statement (where he said he had upper-mid back pain). Though he did not expressly say he accepted it, reading the Arbitrator’s decision as a whole, it was tolerably clear that he took Mr Whyte’s history into account in his ultimate finding in favour of the worker [41]–[42]. The cervical spine injury and the mechanism of injury 5. The Arbitrator dealt with the mechanism of the injury on 28 February 2004 when he referred to the worker’s evidence, the evidence in the medical histories, the Incident Report form of 28 February 2004 and a hand written statement by a Mr Nairn (presumably a work colleague), attached to the Incident Report form. In explaining why he thought it significant, the Arbitrator accepted the worker was grabbed by John, twisted and slammed a couple of times, with some force, into a fence [45]. 6. The Arbitrator’s analysis of the expert evidence demonstrated that, contrary to the appellant’s submission, the Arbitrator did not find that because the incident was capable of causing injury to the cervical spine it also caused injury to the thoracic spine. He found that it was “extremely possible” that the worker also injured his thoracic spine in the same way he injured his neck, namely, by being slammed a couple of times, with some force, into a fence. The Arbitrator found, on the balance of probabilities, consistent with the first finding, that the mechanism of injury and the concession that the worker injured his cervical spine in the incident, supported the conclusion the worker also injured his thoracic spine in that incident [53]. 7. In circumstances where there was no dispute that the incident was particularly violent, or that the worker was slammed backwards into a fence, or that that incident caused injury to his neck and pain in his left shoulder girdle/blade region, the Arbitrator’s reasoning process, and conclusions based on it, disclosed no error [54]. 8. The submission that there was no medical evidence to support the proposition that the mechanism of injury was capable of causing injury to the worker’s thoracic spine ignored the medical evidence and was plainly wrong [55]. 9. An opinion by a suitably qualified expert that it was probable that the worker sustained injury in the manner alleged, when considered with all the other evidence in the case, provided sound support for a finding in the worker’s favour. Even without direct evidence, the inference of causation may be drawn from all of the evidence, including expert evidence as to the possibility that the causal relationship exists (Seltsam Pty Ltd v McGuiness [2000] NSWCA 29) [59]. 23 Alleged failure to find the worker sustained an injury on the balance of probabilities 10. This complaint related to the Arbitrator’s statement that it was extremely possible the worker injured his thoracic spine on 28 February 2004. The complaint was without substance and involved a significant misreading of the Arbitrator’s reasons. The Arbitrator held, on the balance of probabilities, the worker, on 28 February 2004, also suffered an injury to his thoracic spine. The finding demonstrated an application of the correct standard of proof and disclosed no error [63]–[64]. Alleged failure to determine what the injury was and how it was sustained 11. The submission that the Arbitrator failed to determine how the injury was sustained was incorrect. As previously explained, he determined that the injury to the thoracic spine was caused by the mechanism of the injury. In this sense, the Arbitrator was clearly referring to the mechanism of the injurious event or incident. An “incident” is only a mechanism and not itself a s 4 injury (Wyong Shire Council v Paterson [2005] NSWCA 74) [69]. 12. The mechanism of the incident was that John pushed the worker back forcibly into a fence with at least two powerful impacts on two occasions. The trauma and violence of the incident was sufficient to, and did, cause injury to the thoracic spine. That provided a clear and succinct explanation of how the worker injured his thoracic spine. It accorded with both commonsense and logic and clearly satisfied the commonsense test of causation in workers compensation matters (Kooragang Cement Pty Ltd v Bates (1994) 35 NSWLR 452 [70]). 24 Parallel Lines Design Construction Pty Ltd v Bevins [2014] NSWWCCPD 46 Challenge to factual findings founded upon findings as to credibility of witnesses; procedural fairness O’Grady DP 7 July 2014 Facts: This appeal concerned a challenge brought by the appellant to certain findings and orders made by the Arbitrator in proceedings commenced against the appellant by Mr Bevins. Mr Bevins alleged he received injury in the course of his employment with the appellant on 8 April 2011. It was not disputed that at relevant times the appellant was not a holder of a policy of insurance in respect of liability under the 1987 Act and the 1998 Act as is required by the provisions of s 155(1) of the 1987 Act. By reason of the appellant’s non-insurance, the second respondent, the Workers Compensation Nominal Insurer (WorkCover New South Wales) (the Nominal Insurer) was joined to the proceedings as permitted by s 140(1)(a) of the 1987 Act. The injury alleged by Mr Bevins was said to have occurred at a building site located at Mosman. The appellant was the building contractor which had, through its principal and sole director, Mr Walters, contracted with the owners of the property with respect to construction of a new residence. At relevant times Mr Bevins was employed by the appellant as an adult apprentice. Mr Bevins alleged injury to his lower back as a result of lifting a large metal beam from ground level onto the tines or forks of a hoist. It was further alleged that the back injury was caused by the general nature and conditions of his employment with the appellant, involving repetitive bending, twisting and lifting. The principal matter in dispute concerned the question of the occurrence of injury on 8 April 2011. A finding was made that Mr Bevins suffered an injury to his lumbar spine on 8 April 2011 in the course of his employment with the appellant. On appeal, the appellant did not have legal representation. The appellant provided primary submissions as well as a written response to the opposition to the appeal filed on behalf of Mr Bevins and the Nominal Insurer. On 22 May 2014 the appellant filed a document headed “Extra Submission” which addressed the findings on the physical movement of the steel beam on 8 April 2011 and the question of costs. The submissions provided represented an analysis of the Arbitrator’s findings and detailed criticism of the reasoning expressed and conclusions reached by him. It was ascertained at a telephone conference that the fundamental challenge raised on appeal concerned the Arbitrator’s finding of the occurrence of injury. The issue raised was whether the Arbitrator erred concerning his factual finding that Mr Bevins suffered injury as alleged on 8 April 2011. The appellant also asserted that it had been denied procedural fairness and challenged the quantum of weekly payments awarded. Held: The appeal was dismissed. Submissions, discussion and findings 1. The appellant’s submissions directed attention to particular matters found in the reasons as expressed by the Arbitrator and criticism was made founded upon what was stated to 25 be relevant evidence. It is not necessary to repeat the alleged errors. No persuasive argument was advanced in support of the proposition that the Arbitrator’s factual conclusion so affected his reasoning process that any relevant impact upon his orders had occurred. Additionally, the further submissions constituted repetition of argument as put before the Arbitrator and did not establish relevant error [61]–[82]. Quantum of the award 2. The appellant challenged the quantum of weekly compensation awarded by the Arbitrator and asserted that any entitlement would be limited to an hourly rate relevant to payment of adult apprentices. The difficulty with that submission was that there was unchallenged evidence before the Arbitrator as to the quantum of Mr Bevins’ pre-injury earnings, and that evidence was relied upon by the Arbitrator when the quantum of compensation was determined. The award entered by the Arbitrator reflected the finding made as to current weekly wage rate which was based on that evidence. No relevant error was made out [83]. Procedural fairness 3. The appellant emphatically argued that the Arbitrator’s finding that the evidence of the contractor, Mr Fagan, concerning the placement of the hoist was a “recent invention” constituted error. In so finding the Arbitrator accepted Mr Bevins’ submission concerning the credit of Mr Fagan and Mr Walters. In presenting its argument the appellant made reference to the decision of the High Court in Fox v Percy [2003] HCA 22 (Fox). Contrary to the submission advanced by the appellant, the Deputy President was not satisfied that any of the matters raised, either alone or in combination, demonstrated that the Arbitrator’s findings were against incontrovertible facts or uncontested testimony or that the Arbitrator’s decision was glaringly improbable as discussed by the majority in Fox [84]. 26