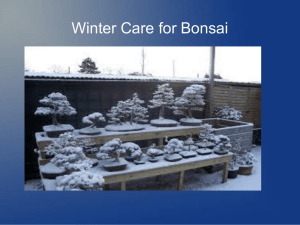

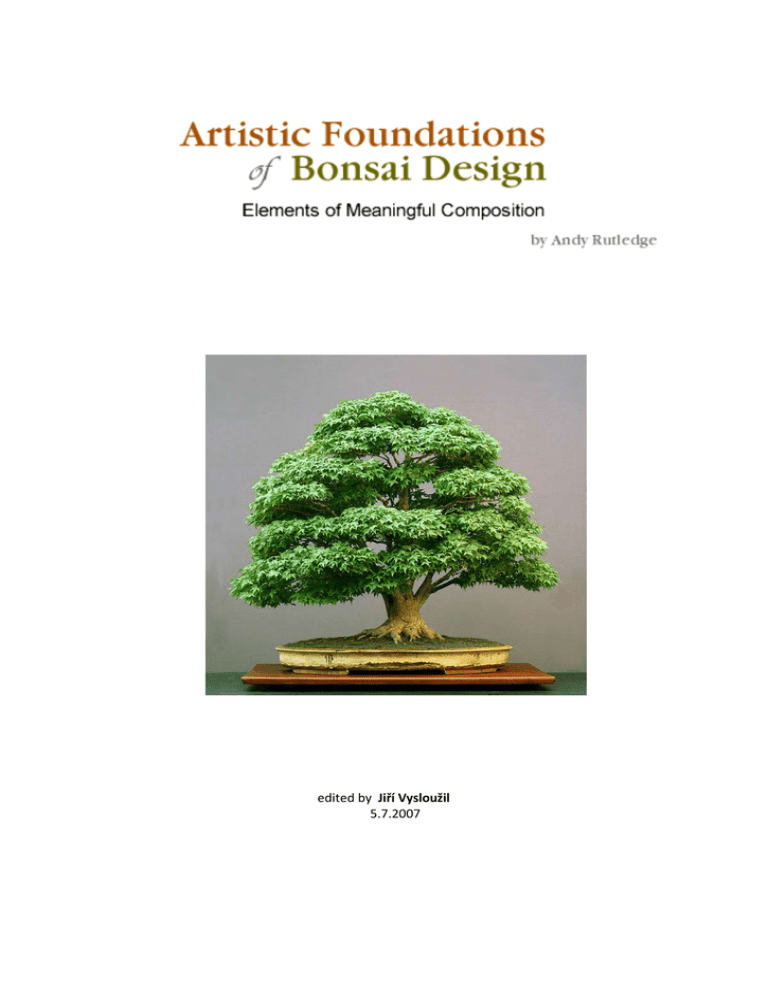

In order to imbue your bonsai with artistic design and composition

advertisement