Chapter 29 EXCHANGE RATES AND MACROECONOMIC POLICY

advertisement

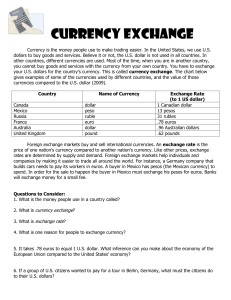

CHAPTER 29 EXCHANGE RATES AND MACROECONOMIC POLICY EVEN NUMBER ANSWERS, SOLUTIONS, AND EXERCISES ANSWERS TO ONLINE REVIEW QUESTIONS 2. Foreigners supply foreign currency (say, in the market where their currency is exchanged for U.S. dollars) because they want to buy U.S. goods and services or U.S. assets. In general economists believe that the supply curve for foreign currency is upward sloping. As the price of foreign currency increases, U.S. goods and services become cheaper. Foreigners buy more U.S. goods and services, and supply more foreign currency to get the dollars with which to buy the goods. The following shift the supply of foreign currency schedule to the right: an increase in foreign GDP, an increase in the relative interest rate in the United States, a change in tastes that makes U.S. goods more desirable to foreigners, a relative decrease in prices in the United States, and an expectation that the foreign currency will depreciate. The following shift the supply of foreign currency curve to the left: a decrease in foreign GDP, a decrease in the relative interest rate in the United States, a change in tastes that makes U.S. goods less desirable to foreigners, a relative increase in prices in the United States, and an expectation that the foreign currency will appreciate. 4. In the very short run, exchange rates move mainly due to changes in interest rates and expectations of future exchanges rates since these forces drive hot money. In the short run, business cycles account for most of the change in exchange rates. Countries with higher relative GDPs demand more foreign currency, causing their own currencies to depreciate. 6. Purchasing power parity says that the exchange rate between two countries should adjust until the average price of goods is approximately the same in the two countries. Exchange rates might deviate from purchasing power parity because of high transportation costs, barriers to trade, and the inherent difficulty in trading some goods. 8. A managed float is when the central bank intervenes in the foreign currency market to prevent an appreciation or depreciation of its currency. Governments use a managed float to help their export-oriented industries, to keep costs down for firms that import inputs, or to decrease the risks of international trade that arise from exchange rate changes. 10. During the 1980s interest rates rose due to the rising budget deficit, a burst of investment spending, and a drop in the private saving rate. All of these contributed to a higher U.S. interest rate, and a capital inflow, as foreigners purchased more U.S. assets than Americans purchased of foreign assets. The dollar appreciated making American goods more expensive to foreigners, and foreign goods cheaper to Americans, and a trade deficit resulted. The trade deficit persisted in the 1990s because of the continuing budget deficit, strong investment spending, and relatively low private savings. PROBLEM SET 2. a. Setting the quantity of pounds demanded equal to the quantity supplied, we have 10 – 2e = 4 + 3e 6 = 5e e = 6/5, or 1.2 dollars per pound. b. After the U.S. government intervenes, the demand for pounds equation becomes 12 – 2e. Resolving for equilibrium, the exchange rate climbs to 1.6 dollars per pound, a depreciation of the dollar. The U.S. government might intervene in this way if it wanted to help its export-oriented industries. 4. Dollars per Peso S1 pesos pesos S2 e1 D1 e2 D2 pesos pesos Quantity of pesos a. As the U.S. interest rate rises, causing a and I to fall, U.S. GDP decreases. The interest rate increase also makes U.S. assets more attractive to Americans and to Mexicans. This, combined with the fall in U.S. GDP, causes the demand curve for Mexican pesos to shift leftward and the supply curve for pesos to shift rightward. The U.S. dollar appreciates. b. The U.S. dollar appreciation causes net exports to fall, further shrinking equilibrium GDP in the U.S. c. If the Mexican central bank raised its interest rates just as much as the United States, then the dollar would not appreciate as much. (It might still appreciate somewhat, depending on the relative decline in U.S. and Mexican GDP, and the impact of these declines on U.S. net exports). While U.S. output would still fall, it would not fall as much as in the initial analysis. 6. a. b. A fixed rate of 1.41 dinars per dollar is the equivalent of $0.71 per dinar. Since this is higher than the market equilibrium price of $0.50 per dinar, Jordan’s central bank must buy dinars to keep the dinar from depreciating. c. Jordan would eventually run out of foreign reserves, and so could not buy dinars forever. d. An expected fall in the dinar causes the supply curve for dinars to shift rightward from S 1 to S2and the demand curve to shift leftward D1 to D2. e. The end result is that Jordan’s central bank must buy even more dinars to maintain the fixed rate. 8. Since Country B has the higher inflation rate, its relative price level is rising. As its basket of goods becomes relatively more expensive, only a depreciation of its currency 10. can restore purchasing power parity. Traders would buy Country A’s currency in order to buy its goods for resale in Country B. Country A’s currency will appreciate relative to Country B’s (alternately stated: Country B’s currency will depreciate relative to Country A’s). Since the trade deficit at point B equals 2,000 billion yen, and since the exchange rate is $0.01 per yen, the trade deficit measured in dollars is 2,000 billion x $0.01 = $20 billion. MORE CHALLENGING 12. More spending by the U.S. government causes U.S. interest rates to rise. This makes U.S. assets more attractive, increasing the supply and decreasing the demand for foreign currency. The dollar appreciates, causing net exports to fall, thus reducing real GDP. This makes fiscal policy less effective in changing equilibrium GDP than it would be if the effects on exchange rates were excluded.