Chapter 7

advertisement

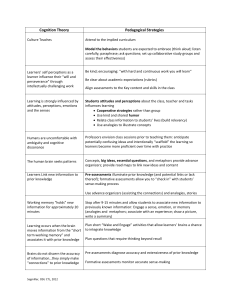

Chapter 7 Formal Group Assessment: Focus on Accountability Introduction • What Is the Context for Formal, Standardized Assessment? • Characteristics for Formal, Standardized Testing • Group Achievement Tests for Instructional Planning and Progress Monitoring • High-Stakes Testing • Formal Group Achievement Testing for Accountability • The NAEP and the NAAL • What do Group Norm-referenced Measures of Reading Look Like? • Special Considerations for Formal, Group Assessment of Adult and English Language Learners What Is the Context for Formal, Standardized Assessment? Tips for Administering and Scoring Formal and Group Tests • Refer to Text Box 6.5 for tips. • Follow scripted directions in manual to prevent error. • Refer to Figure 6.1 to understand how various scores relate to each other on the “normal curve.” • Group formal tests can be useful for gross progress monitoring, limited instructional planning, screening and whole class comparisons. • Primary purpose is accountability. Figure 6.1 Figure 7.1 Figure 7.2 Group Achievement Tests for Instructional Planning and Progress Monitoring Brief Assessments of Oral Reading Fluency • Test of Silent Word Reading Fluency-2 • Test of Silent Contextual Reading Fluency-2 • Can be individually or group administered (PRO-ED) Figure 7.4 Group Reading Tests: Some Examples • Gates-MacGinitie, 4th Edition (Riverside) • Gray Silent Reading Test (PRO-ED) • Nelson-Denny Reading Test (Riverside) Figure 7.5 Figure 7.6 Test of Adult Basic Education • Test of Adult Basic Education (TABE, 2014) • TABE is commonly used in adult education settings across the U.S. and provides a measure of reading. • Teachers are encouraged to first administer a locator test to help determine the most appropriate level of administration for entering students. High-Stakes Testing How did high-stakes testing originate? • 1946: U.S. Chamber of Commerce called for an assessment system to ensure that schools prepared well-qualified workers for the post-World War II era (Fine, 1947). • Cold War era of 1950s through 1970s: nonflattering international comparisons of student performance combined with the fear of losing U.S. scientific and military superiority fueled a frenzy of educational reform (Postlethwaite, 1985). Origins of high-stakes testing Two additional motivating influences: • In late 1960s and 1970s—the interest of state governments to provide evidence of teacher accountability • A growing number of lawsuits brought by parents of semiliterate graduates against school systems for not properly educating their children (Conley, 2005) Guidelines for High-Stakes Testing • Elliott, Braden, & White (2001) provide suggestions for highstakes testing: • Tie assessment to predetermined goals • Rely on multiple measures • Create reliable and valid tests for purposes intended Standards for Testing • Table 7.1 • Sample Standards from AERA, APA and NCME’s Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing (2014) Should we Teach to the Test? Popham’s Categories of Test Preparation Practices • 1. Previous-form preparation allows students to practice test taking with items from old out-of-print versions of a test that is currently used. • 2. Current-form preparation allows students to practice on items taken directly from a currently used version of a test. (Popham, 2002) Popham’s Categories con’td • 3. Generalized test-taking preparation allows simulation of test administration using a variety of test-preparation strategies to fit a variety of test formats (e.g., helping students schedule time optimally, modeling good calculated guessing strategies, and encouraging students to read the stem carefully before looking at the options of multiple-choice questions). Popham’s Categories cont’d • 4. Same-format preparation allows students to practice responding only to items that represent the content of the actual test and mirror the format of the items from the test. • 5. Varied-format preparation allows students to practice responding to items that represent directly the content of the actual test using a variety of item formats. Popham’s Recommendations Which of the above are appropriate (i.e., educationally defensible and ethical)? • #3 (Generalized test-taking preparation) • and #5 (Varied-format preparation) Controversies and Criticisms of Group Testing • Table 7.2 • External Testing Programs: Criticisms and Solutions (Payne, 2003) High-stakes testing of students with disabilities and English language learners • Most take same group achievement tests as students without disabilities and/or whose first language is English. • Students with disabilities may have accommodations if documented in Individual Education Plans (IEP) or Section 504 Plans. Typical Accommodations for Students with Disabilities • • • • • • • • (a) large print (b) oral instructions (c) calculators/mathematical tables (c) flexible setting (e.g., individual versus small group versus study carrel) (d) visual/tactile aids (e) multiple testing sessions (within the same day) (f) flexible scheduling (g) use of a scribe/recording device Typical Accommodations • (h) test booklet marking • (i) oral self-reading • Other accommodations, sometimes referred to as “special accommodations,” include: (a) extended time; (b) read aloud internal test instructions/items; (c) prompting, upon request; (d) use of an interpreter; (e) use of manipulatives for math tests; and (f) use of assistive technology. Formal Group Achievement Testing for Accountability Two Well-Known Examples: National Assessment for Educational Progress (NAEP) The National Assessment of Adult Literacy (NAAL) NAEP • http://nces.ed.gov/nationsreportcard/ • Table 7.4 • National Association of Educational Progress Performance Descriptions • Basic • Proficient • Advanced • Grades 4, 8, 12 Trends in NAEP Performance • National averages were 2 points higher in 2005 than in 1992 and 4 points higher in 2013 than 2005 at grade 4. • Similar trends for students in grade 8 • Scores for 4th grade Asian/Pacific Islanders, Blacks, Hispanics, and Whites increased between 1992 and 2013. Students within all four groups improved slightly from 2011 to 2013 and all improved significantly from 1992 to 2013 • Gains by White and Black 8th grade students parallel 4th grade; however, 8th grade Hispanic students gained 15 points from 1992 to 2013 versus a 10 point gain for 4th grade; 8th grade Asian/Pacific Islander students gained 12 points versus 19 points for 4th grade. • In spite of these gains for 8th grade, Asian/Pacific Islander students scored highest in 2013 (280 points), followed by White (276 points), Hispanic (256 points), and Black students (250 points). Trends in NAEP Performance • Males seem to be closing the reading gap slowly. • 25% and 32% of 4th grade males earned Proficient or better scores in reading in 1992 and 2013, respectively. • 32% and 38% of 4th grade females earned Proficient or better scores in reading in 1992 and 2013, respectively . • The same trend is observed for 8th grade students. • Percentage of Proficient or Above 12th grade students decreased slightly from 1992 to 2013. • Consequence of more students staying in school? Table 7.3 Achievement Level Results* from the National Assessment on Education Progress Fourth Grade Eighth Grade Year Below Basic Basic Proficient Advanced Below Basic Basic Proficient Advanced 1992 38 34 22 6 31 40 26 3 2011 33 34 26 8 24 42 30 3 2013 32 33 27 8 22 42 32 4 * in percentages NAAL • www.nces.ed.gov • Some gains from 1993 to 2003 were noted in adults’ quantitative literacy and document literacy. • But in 2003: • 30 million adults (14%) performed at Below Basic level (answered either none or only the most simple and concrete items); • 63 million (29%) were able to answer simple and everyday literacy-based questions; • 95 million (44%) were able to participate in moderately challenging literacy activities; • 28 million (13%) could perform complex and challenging literacy activities. Common Core State Standards Assessment • In 2010, as part of the Race to the Top initiative, the U.S. Department of Education awarded $330 million to two entities to develop valid, fair, “next generation” assessments in English/Language Arts (ELA) and Mathematics that would yield faster results than traditional group tests: • Partnership for Assessment of Readiness for College and Careers (PARCC) • http://www.parcconline.org/ • Smarter Balanced Assessment Consortium • http://www.smarterbalanced.org/ Common Core Assessments • Both have summative and formative assessments • Goal is to assess via computer technology • Smarter Balanced assessments are computer-adaptive What do Group Norm-Referenced Measures of Reading Look Like? Typical Group Achievement Test • Table 7.5 • Scope and Sequence Chart from Stanford Achievement Test Figure 7.6 Figure 7.7 Assessment at a Glance: Formal, Group Assessment • Tables 7.6 and 7.7 • Characteristics of Formal, Group and Norm-Referenced Assessments of Reading • Psychometric Properties of Formal, Group, Norm-Referenced Assessment of Reading Special Considerations for Adults and English Language Learners Special Considerations for Group Assessment of Adults • See Text Box 7.1 • Assess adult learners’ educational histories, background experiences, and interests, as well as specific reading skills. • For those who score below 8th grade level on the Test of Adult Basic Education, further skill assessment is needed. • Multiple measures will likely be needed to gain a complete assessment of adult learners’ strengths and weaknesses. • Ensure that tests used for adults are normed for adults. • Adult learners may feel particularly conscious of their performance in a group testing situation; take special care to put them at ease and ensure confidentiality of scores. • Refer to the Adult Reading Components website to plug in scores and get educational recommendations for adult learners: https://lincs.ed.gov/readingprofiles/ Special Considerations for Group Assessment of ELLs • See Text Box 7.2. • NCLB requires that ELL students participate in group achievement testing for accountability purposes. Be familiar with the accommodations allowed in your state and school district. For example, some states allow directions to be read in the students’ native language; some allow for flexible grouping, etc. • Prepare ELL students for group assessment by providing practice sessions. Address their questions or concerns to relieve anxiety. (We like what one of our children’s teachers told her class—“This test is to show if I did a good job this year as your teacher. Just do your best and don’t worry about it.”) • Work with bilingual and English as Second Language instructors to inform parents about the purposes of group achievement testing to relieve anxiety and to ensure parental support. • Be aware of the limitations of testing students in a second language when interpreting assessment results. Assessment at a Glance: Formal, Group Assessment • Tables 7.6 and 7.7 • Characteristics of Formal, Group and Norm-Referenced Assessments of Reading • Psychometric Properties of Formal, Group and NormReferenced Assessments of Reading Summary • What is the Context for Formal, Standardized Assessment? • Characteristics for Formal, Standardized Testing • Group Achievement Tests for Instructional Planning and Progress Monitoring • High-Stakes Testing • Formal Group Achievement Testing for Accountability • The NAEP and the NAAL • What do Group Norm-Referenced Measures of Reading Look Like? • Special Considerations for Formal, Group Assessment of Adult and English Language Learners