Seniorseminar

advertisement

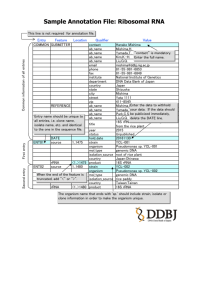

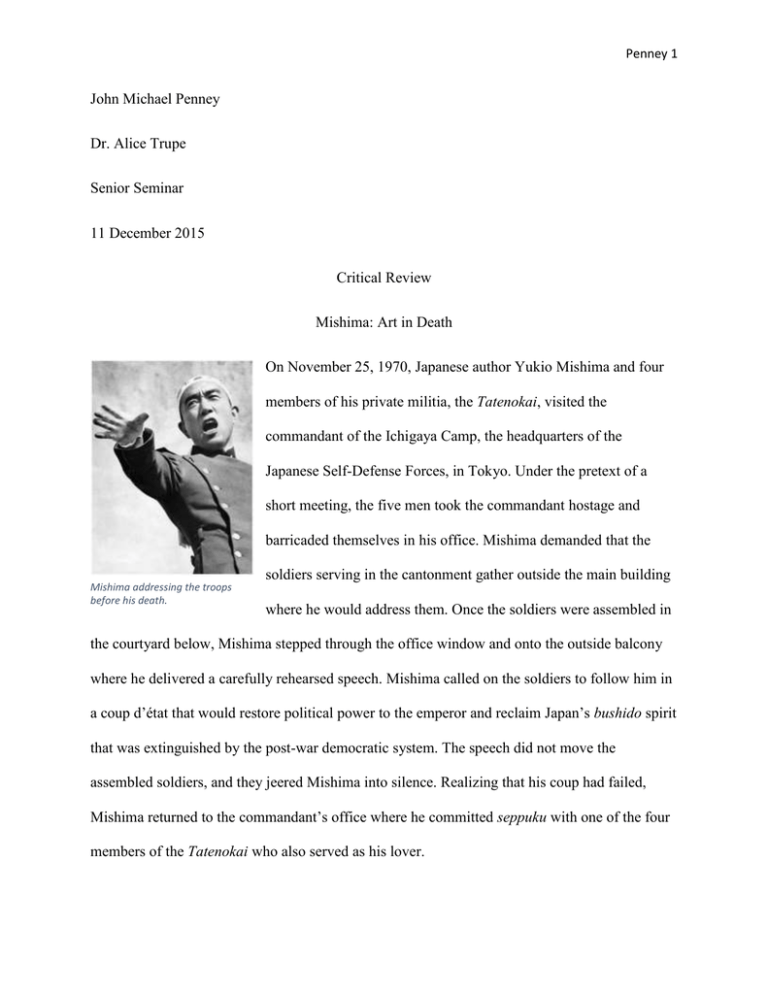

Penney 1 John Michael Penney Dr. Alice Trupe Senior Seminar 11 December 2015 Critical Review Mishima: Art in Death On November 25, 1970, Japanese author Yukio Mishima and four members of his private militia, the Tatenokai, visited the commandant of the Ichigaya Camp, the headquarters of the Japanese Self-Defense Forces, in Tokyo. Under the pretext of a short meeting, the five men took the commandant hostage and barricaded themselves in his office. Mishima demanded that the Mishima addressing the troops before his death. soldiers serving in the cantonment gather outside the main building where he would address them. Once the soldiers were assembled in the courtyard below, Mishima stepped through the office window and onto the outside balcony where he delivered a carefully rehearsed speech. Mishima called on the soldiers to follow him in a coup d’état that would restore political power to the emperor and reclaim Japan’s bushido spirit that was extinguished by the post-war democratic system. The speech did not move the assembled soldiers, and they jeered Mishima into silence. Realizing that his coup had failed, Mishima returned to the commandant’s office where he committed seppuku with one of the four members of the Tatenokai who also served as his lover. Penney 2 Yukio Mishima is a notorious and revered figure in Japan and around the world. Nominated three times for the Nobel Prize in Literature throughout his lifetime, Mishima was more than just a writer; he was also an actor, bodybuilder, director, political activist, and sportsman skilled at kendo, the martial art of Japanese sword fighting. Born Kimitake Hiraoka in 1925, Mishima grew up a sickly boy whose custody was split between an overbearing grandmother and doting parents. When he was drafted to fight in World War II, Mishima was misdiagnosed with tuberculosis and declared unfit for service. He would regret not serving in the war for the rest of his life. Millions of young men fought and died for the cause of Japanese imperialism, and Mishima himself openly longed for the missed opportunity to have died fighting, which is reflected in much of The Writer as actor in the 1960 Yakuza film, Afraid to Die. his writing. His longing for death would eventually evolve into an obsession with homoerotic, masochistic beauty that was embodied by the young soldier he never was. Many of Mishima’s books, such as Confessions of a Mask, The Temple of the Golden Pavilion, Forbidden Colors, and Sun and Steel, openly express the author’s taboo and avant-garde obsessions. Some have speculated that Mishima’s attempted coup in 1970 was not born from any deeply held nationalistic sentiments; instead, Mishima’s commitment to the far right was merely a ruse for the meticulously planned death that he always wanted. If Mishima’s death was truly an elaborate piece of public spectacle, then the end of his life is the final manifestation of his writing and his obsessions. Confessions of a Mask, published in 1949, was Mishima’s first big hit. It is also one of his most telling book,s because the story was highly autobiographical and honest about Mishima’s masked sexuality. Kochan, the protagonist, grows up during the height of Japanese Penney 3 militarism. He is a small and weak boy, shielded away from normal society by his family during his formative years, which implanted a feeling of isolation that evolved into obsessions with masochism and death. Kochan is a homosexual; but, as he grows up, he realizes that homosexuality is scandalous to his society’s sensibilities. Because he has to hide his identity as a homosexual in a highly conservative and militarized culture, his sexuality festers into dark fantasies. In a famous scene in the first chapter, Kochan experiences his sexual awakening while staring at a picture of St. Sebastian, an early Christian martyr. The picture shows the saint slung to a tree and shot with arrows. Kochan describes the morbid and mysteriously erotic picture as something “that had been lying in wait … for [him], for [his] sake” (Confessions 38). The description that follows the revelation is so Mishima as St. Sebastian -- the man fulfilling a childish fantasy. intimate in detail that it has to be autobiographical, although embellished for the purpose of drama. The image of St. Sebastian’s suffering for his faith surely made an impression on the young Mishima, an impression that persisted throughout his life and touched on many of his obsessions. The young, strong warrior suffering gracefully for a higher cause and, in doing so, becoming an idol, is the very thing that Mishima desired. Indeed, after taking up bodybuilding, he would stage photographs of himself as St. Sebastian. By the time Confessions of a Mask was published, Mishima was still a young man in his early twenties, and grappling with his desires. Although he had exposed himself through his novel through masochistically-charged homoeroticism, Mishima was not yet fully formed. His prose was lofty and crude whenever he described his fantasies and seminal sexual moments. Penney 4 The young Mishima had not fully grasped the sublime beauty that he wanted to struggle with, in his writing and in his life. The opportunity to grapple with beauty comes in 1956 when Mishima publishes his seminal book, The Temple of the Golden Pavilion. Considered by many to be his greatest novel, The Temple of the Golden Pavilion is based off of a true story. The novel’s protagonist, Mizoguchi, is a stuttering young man with an ugly face. Since his youth, Mizoguchi’s father has told him stories of the temple’s beauty and, over the course of the novel, Mizoguchi becomes hatefully obsessed with an image of the temple in his mind. He believes that the temple’s pristine beauty is mocking his own ugliness, which renders him impotent in everyday life and in sexual encounters. Mizoguchi wishes that American bombers will come to Kyoto and destroy the temple during the during the fire bombings; however, his grim fantasy never comes to pass. Years go by and Mizoguchi becomes more and more spiteful of himself, the temple, and everything around him. Eventually, he takes it upon himself to destroy the temple. He lights bales of hay on fire inside its chambers and, in the “For clearly it is impossible to touch eternity with one hand and life with the other” (Temple 220). hope of dying a beautiful death, he tries to gain access to the heart of the temple where he plans to give himself up to the flames; however, the door won’t open as smoke consumes everything around him. Feeling like a beautiful death has been denied him, the book ends with Mizoguchi forgoing suicide. He leaves the immolated building and finds a safe distance to watch it burn. Mishima used Mizoguchi as a mouthpiece for his obsession with unattainable beauty that must be destroyed by the observer in order to be freed from its haunting perfection. Mishima writes in The Temple of the Golden Pavilion that when “people concentrate on the idea of Penney 5 beauty, they are … confronted with the darkest thoughts that exist in this world” (Temple 48). While Confessions of a Mask revealed Mishima, the masochist homosexual, The Temple of the Golden Pavilion revealed Mishima, the nihilistic aesthete. Mishima’s homosexuality and nihilistic aestheticism is explored in an earlier novel, Forbidden Colors, published in 1951. Like Confessions of a Mask, there is autobiographical material to be found in the book. Shunsuke, an aging writer popular in post-war Japan meets Yuichi, a handsome young man, during a vacation. Yuichi is gorgeous and irresistible to women because of his good looks and simple character. He’s engaged to marry a young and beautiful woman who he feels nothing for. Yuichi confides in Shunsuke that he is actually a latent homosexual, much to Shunsuke’s devious delight. Shunsuke, who Mishima's marriage to Yoko in 1958 was a public spectacle used to mask his true nature. has been spurned by women and bad relationships all of his life, wants to use Yuichi as an affront against womanhood. He tells the young man to go through with the marriage and indulge in his homosexuality. By encouraging the irresistible young man to marry someone he doesn’t love while simultaneously diving into Japanese gay culture, Shunsuke believes that Yuichi will be denying women’s carnal interests and thus avenging Shunsuke’s failed love life. Forbidden Colors represents a multiplicity of Mishima’s personality. It connects his idea of homoerotic beauty to the physical male form that’s devoid of intellect as seen in the character of Yuichi. Yuichi’s character stands separate from Kochan from Confessions of a Mask. Kochan is a homosexual like Yuichi, but Kochan is endlessly intellectual and self-reflective while Yuichi is not. Yuichi’s marriage and homosexuality mirrors Mishima’s own to Yoko Sugiyama in 1958. Mishima specified that his bride should have no interest in his literary work; and, after the Penney 6 marriage, he kept his sordid love affairs with young men secret from her. For Mishima, beauty could only come from youth and from men. He feared aging and the old, which takes the form of Shunsuke. Mishima’s fear appears in Yuichi when the youth trolls a park and meets an older gay man, trying to appear younger: Silently, Yuichi handed him his cigarette. The youth turned his oval face. Seeing that face more distinctly, Yuichi shuddered. The veins in the man’s hand, the deep wrinkles at the corners of his eyes, were those of a person well past forty. The eyebrows were meticulously blackened; the ageing skin lay masked beneath the theatrical make-up. His unnaturally long eyelashes, too, could not possibly be genuine. (Forbidden Colors 64) Furthermore, Shunsuke is a character that would come to represent the archetypical villain in Mishima’s life—an old, ugly intellectual devoid of athleticism and strength. The characters lack of sex appeal, and the emphasis on the mind rather than the body, was everything that Mishima feared becoming as he grew older. The essay Sun and Steel is the natural conclusion to Mishima’s literary life. Published two years before his dramatic suicide, the subtitle for the personal essay—Art, Action and Ritual Death—captures all the themes that Mishima’s major works expounded on since the publication of Confessions of a Mask in 1949; however, it was also a work that denied his legacy as a writer. An ongoing theme that Mishima writes about in Sun and Steel is the power that words have had on his life Mishima as a man of action. since his childhood and how he detests their decaying power. Words, he writes, have a “corrosive power” like nitric acid upon a plate of copper used for etching (Sun and Steel 12). Penney 7 Furthermore, Mishima admits to suicidal ideations. He writes quite candidly that “[he] cherished a romantic impulse towards death, yet at the same time [he] required a strictly classic body as its vehicle; a peculiar sense of destiny made [him] believe that the reason … [his] impulse towards death remained unfulfilled in reality was the … fact that [he] lacked … the physical qualifications” (27). Mishima goes on to detail his lifetime hobby of bodybuilding, his time training alongside his private militia, and his desire to become a tragic man of action and remove himself from the world of words into the world of pure action—a world of sun and steel. Mishima’s frank admission towards a desire for a strong, classical body to use as a vehicle towards a romantic death in Sun and Steel seem to imply that his conversion to right wing politics in his later life was disingenuous. Demanding that political power be restored to the emperor while dressed as a modern day samurai was simply a means to an end; to accomplish the perfect death he always longed for,`` like in the picture of St. Sebastian from Confessions of a Mask. Similarly, the Tatenokai was an extension of his desire for homoerotic, youthful beauty embodied by the young soldier. At the age of 45, Mishima certainly thought that he could no longer be like the beautiful Yuichi from Forbidden Mishima's grave in Tama Cemetery. Colors and he was becoming someone like Shunsuke, no matter how many weights he lifted, and so he found good looking young men like Yuichi to follow him in his death wish. What Mishima wanted, like Mizoguchi in The Temple of the Golden Pavilion, was to stand before the eternal beauty and snuff it out. That meant committing the ultimate, heroic action and then dying in the process. Mishima never truly sought to change Japan’s political landscape, he only wanted to die and embody in death what he wrote about in life Penney 8 Work Cited Mishima, Yukio. Confessions of a Mask. Trans. Meredith Weatherby. New York: New Directions, 1958. Print. Mishima, Yukio. Forbidden Colors. Trans. Alfred H. Marks. New York: Knopf, 1968. Print. Mishima, Yukio. Sun and Steel. Trans. Bester John. Tokyo: Kodansha International, 1968. Print. Mishima, Yukio. The Temple of the Golden Pavilion. Trans. Ivan Morris. New York: Knopf, 1959. Print. Illustrations Juan. St. Sebastian. Digital image. 4ever&ever. Blogspot, 07 Feb. 2012. Web. 11 Dec. 2015. Kinkaku-ji. Digital image. Travelneu. Travelneu.com, 3 Mar. 2012. Web. 11 Dec. 2015. Lotosesser. Grave of Yukio Mishima on the Tama Cemetery. Digital image. Wikipedia Commons. Wikipedia, 2007. Web. 11 Dec. 2015. MadMonarchist. November 25, 1970. Digital image. The Mad Monarchist. Blogspot, 24 Jan. 2013. Web. 11 Dec. 2015. Movieposter-japan! Afraid to Die Poster. Digital image. EBay. Movieposter-japan!, 02 July 2015. Web. 11 Dec. 2015. Wheeler, Welcott. Yukio Mishima's "Patriotism": Japanese Fascism and Its Terrible Heritage. Digital image. The World of Welcott Wheeler: A Writer's Website. Welcott Wheeler, 13 Mar. 2007. Web. 11 Dec. 2015. Penney 9 John Michael Penney Dr. Alice Trupe Senior Seminar 13 December 2015 Creative Essay Memories that Ring from Brass Bridgewater, Virginia. 2015. December. My name is Michael Penney. I have in my possession a little brass cup and hammer. It was given to me by Japanese grandmother when I was sixteen years old. She received the cup from her father who purchased it in India while on a business trip. When she gave it to me, she told me that it was a special item used during Buddhist rituals. Whoever taps the edge of the cup with the hammer summons their ancestral spirits and wards off evil. At the time, I wasn’t impressed with the heavy, old cup whose bottom was greening with age. As I’ve grown older and more superstitious, the cup has grown on me. It’s a physical connection to a familial lineage I know very little about. The cup takes on mythical properties as it sits on my desk and collects dust. Sometimes when I’m alone and the house is empty, I go up to my room and pick up the bowl and hammer from off my desk. I blow off the dust and weigh the heavy brass in the palm of my hands. Every mark and scratch on its surface whispers a forgotten story in a language I do not understand. I meditate on whether I should clean the bowl with brass cleaner in order to Penney 10 restore it to some former glory, but my heart tells me to leave it as it is. To clean away the ancient grime would wash away some malleable memories that are better left intact. It would soil my family history. I am not a man that indulges in foolishness. While there is a hidden part of my secret soul that is superstitious, I do my best to ignore that romantic itch while I go about my day in the modern world. But when I hold the cup, the hairs on the back of my neck stand on end. By its very nature, it is a haunted item. More potent than an ouija board, the cup only needs a tap from the hammer in order to summon spirits. Sometimes I play along with myself and tap the edge. Sometimes I don’t. When I do, the cup sings with a subtle sound that vibrates the air around my ears. The sound lasts for several seconds before it fades away. In those seconds, I close my eyes and remember memories that are not mine. ~*~ Sydney, Australia. 1941. December. My name is Tomimori Seiko. I sat in the living room, reading between a thin beam of morning sunlight that shined through the drawn velvet curtains. It was Oscar Wilde’s The Importance of Being Earnest. I didn’t understand all of the words, but I wanted to challenge myself. Father had not let me attend university in over a week, and I had fallen behind in my studies. Being a diligent student, I had a friend, Samantha, bring me lesson notes and homework to the house, but Samantha hadn’t come by in three days. So I read and reread my English books, practicing the words out loud while trying to mask my Japanese accent. Penney 11 Maybe Samantha had stopped coming to see me because I was Japanese. My sister, Kimiko, and I had been listening to the radio earlier. The Imperial Navy had attacked America at Pearl Harbor. The Imperial Army had swept through Malaya and looked poised to take Singapore. Australia was tense. As a Commonwealth nation, people thought that maybe Australia would be attacked too. Even invaded. In the days since the attack on Pearl Harbor, a lot of students in my classes had given me ugly looks, but they never said anything. Father pulled me out of university soon afterwards. It was like Father knew something was going to happen. Days before the attacks, he told Kimiko and me to keep the curtains around the windows closed, to only turn on the electric lights if we needed to, and not to answer the phone or the door. It was like he wanted to pretend like we were ghosts. Like no one actually lived in the house on the busy street in the heart of Sydney. Only the butler was allowed to move around freely. It was bothersome for me because it made it hard to study. The living room door opened. Kimiko walked in while holding a newspaper. “Merry Christmas,” she said with a sardonic tone while carefully handing me the newspaper. “It’s Christmas?” I asked with surprise. “It was two days ago,” Kimiko replied while taking a seat next to me. She produced a comb from her high school uniform’s pocket and began to brush her hair while possessing a look of quiet intensity. “Seiko, read the newspaper.” I looked at the newspaper she had handed me. The headline read in big, bold letters: HONG KONG FALLS TO JAPAN! Without reading further, I set it on my lap and looked at my sister. “When did this happen?” Penney 12 “Two days ago,” she said. She furrowed her brow, which made her young face look ten years older. “On Christmas day.” “Oh.” I said dully, unsure what to make of the rapidly changing events. Kimiko and I split our time between Australia and Japan. We studied in Sydney and lived in Kobe. Father worked as the director of Kanematsu Ltd’s Australian branch, which shipped wool from Australia to Japan. Because of Father’s position, we had the privilege to study abroad, which wasn’t something that many young Japanese had the opportunity to do. When we were not in Sydney, we went home and lived with Mother and our younger sister, Yoko. Our time divided between Australia and Japan left Kimiko and me feeling strange. In Japan, we’re told to cheer the nation on as we expanded our empire throughout Asia. We’re told that we Japanese were a divine race that were destined to lead Asia out of Western imperialism. In Australia, we’re told that Japan was committing atrocities in China and Manchuria, and that we were just as bad as Hitler in Europe. Kimiko and I didn’t know what to believe, but Father advised us to keep our heads down and only worry about our studies. “Are you going to school?” I asked Kimiko while looking at her uniform. “No,” she said. “Father told me that I’d be staying home with you from now on.” “When did he tell you that?” “Three days ago.” “So before this?” I asked, gesturing to the newspaper on my lap. “Yes. I don’t know how he does it. I don’t know why he’s making us live like this.” Penney 13 I didn’t know either. Father was a businessman. He couldn’t possibly have known about what the government in Tokyo had planned or what the army and navy would do around the world. But it seemed like he was carefully responding to events before they occurred while trying to draw as little attention to himself and us as possible. “Do you think Father will send us back to Kobe?” “I don’t know,” Kimiko said while fiddling with brush. “Maybe. Maybe he thinks it will be safer there with Mother and Yoko. What about school?” “People in my classes didn’t like my Japanese face after Pearl Harbor,” I said gloomily. “Seiko!” Kimiko suddenly exclaimed, “What if Japan attacks Australia? What do you think will happen to us? Or Father?” “I don’t know.” “I don’t want to go back to Kobe. I like it better here. I have friends here. If we go to Japan, the government will make us work in factories making boots for the army!” Kimiko was a smart girl that kept up with the news more than me, but it was moments like this that made me remember she was five years younger. She was always being babied by our parents, and so she had a weak constitution when she was stressed. “It’ll be okay. I’m sure Father knows what needs to be done.” “Do you think we were right?” Kimiko asked, putting a hand to her mouth. “Right doing what?” “Do you think Japan was right attacking America and the British?” “Japan was foolish for attacking America,” came a voice from the hallway. Penney 14 Kimiko and I looked towards the door. Father was standing at the threshold, tying his necktie around his shirt collar. He looked put together and handsome as always, but he also looked stressed. I could smell his aftershave from across the living room, and I noticed that he had a small cut from shaving on his chin. “Father,” I stood up and exclaimed. “How long have you been standing there?” “For only a moment,” he replied, tucking his necktie into his waistcoat. “Only enough to answer your sister’s question.” Kimiko was quiet, bowing her head respectfully in Father’s direction. At that moment, I did not share her deference. “Father, you shouldn’t say such things out loud. What if the Kempeitai were to hear you saying Japan was foolish for doing anything?” Father walked into the living room, followed by the butler, Jae-suk, who was holding his suit jacket. “The Kempeitai do not operate in Sydney,” he said with a knowing smile. “We can speak freely here.” I watched Jae-suk silently hand Father his jacket. He slipped it on with a single, graceful motion. Jae-suk produced a handkerchief from his own jacket pocket and handed it to Father. Father dabbed the small cut on his chin and looked at it to make sure he wasn’t bleeding. After he was done, he turned to me and held out his hand. I knew instantly that he wanted the newspaper. I got up and handed it to him. He read the headline to himself and handed the newspaper to Jae-suk. “Are you going to send Kimiko and me back to Kobe?” “Why do you ask?” Penney 15 “Because you’re not letting us go to school. You’re not letting us leave the house or do anything. Why should we stay here?” Father locked eyes with me. His gaze embarrassed me, and I flinched. “Impetuous child,” he scolded. “Maybe.” “When will you tell us?” I asked, struggling to hold his gaze. “Tonight. Maybe tomorrow.” I continued to hold Father’s gaze. We both stood quietly next to each other. Jae-suk and Kimiko watched us without moving. In Father’s eyes, I sensed a feeling of unknown strain. Like there were matters in his heart and mind beyond family and work. In that moment, his eyes became my eyes. I bowed dutifully to him and sat back down next to Kimiko. ~*~ Sydney, Australia. 1941. December. My name is Tomimori Kenkichi. “I’m going to the office,” I said shortly. “I’ll be home later this evening. If you need anything, ask Jae-suk. Do not open the door. Do not answer the phone. Do not open the blinds. Be as quiet as you can.” “Yes, Father,” Kimiko and Seiko said at once, their heads bowed. I could sense their uneasiness. Pulling them out of school and keeping them locked away at home had made the girls tense. But it had to be done. They didn’t know what it meant to be Japanese right now. They also didn’t know what other people thought it meant to be Japanese. It Penney 16 was best to keep them at home where it was safe. “If you’re good, we’ll listen to the radio tonight after I get home. We’ll listen to some show tunes.” From outside the window, I heard the sound of a car pull up next to the house. “Your car, sir,” Jae-suk said slowly. “Has arrived.” I walked towards the hallway with Jae-suk in my wake. Before leaving, I turned and looked at my daughters. They were standing and bowing in my direction. I left the room without saying another word. At the door, Jae-suk handed me my silver pocket watch. I turned the crown a few times before plucking it into my waistcoat pocket. “Keep an eye on them,” I said to the butler. “Don’t let their womanly sullenness get the better of them.” “Yes, sir,” Jae-suk said. He opened the front door and I stepped out into the morning light. The street outside the house was busy with cars driving up and down the road. Lined with other houses that shared a drab uniformity, they reminded me of the newer buildings being built in Kobe. A young white man was standing at the curb next to a running black sedan. He was dressed in a drab brown suit and he was smoking a cigarette. When he saw me at the door, he dropped the cigarette and stamped it out with his foot. “Good morning, Tomimori-san,” the young man said. “I’m Joe. Joe O’Donnell. Greg’s son.” “Good morning,” I said in English with a measured voice. “Where is my usual driver?” Penney 17 “Called out sick, sir. Said he’d be out for a week. Didn’t say with what. My dad told me to come and get you. Told me to be here quick like seeing as how you’re a busy man.” I looked at Joe and then back up to my door where I met eyes with Jae-suk. Greg O’Donnell was my white Australian secretary. He normally called if something was the matter. Without looking at Joe, I said, “Thank you. I am busy. Let’s go now.” Joe opened up the door to the back of the car. I got in and he took his place in the driver’s seat. When he had gotten comfortable, Joe adjusted the rearview mirror and began driving down the road. “How long you been in Sydney, Tomimori-san?” “Five years,” I said, looking around the car. It was nicer than the car I usually rode. The leather upholstery was finer, and the car smelled newer. It wasn’t something that someone like Joe, much less his father Greg, could afford in this economy. “That’s a long time. Dad told me that the company went through a couple of heads before you came around. You get back home often? See family?” “On holidays,” I responded, narrowing my eyes. “Kobe? “Yes.” Joe drove in silence for the rest of the way. It wasn’t until we got to the heart of the business district did he say anything else. He got out of the car and opened the door for me. “It was good talking to you, Tomimori-san. See you this evening.” I got of the car without saying anything. I ascended the steps to the office entrance where a doorman opened the door for me. Once inside, I was instantly set upon by Greg O’Donnell. Penney 18 “Good morning, Mr. Director,” he said in a small voice that matched his small head. “You’re five minutes late. I have your schedule here. There’s a gentleman already waiting to see you.” “Good morning. Apparently my driver is sick. Your son picked me up. Why was I not informed?” “My son?” O’Donnell said, surprised, while we walked towards my office. “My son is in Europe, Mr. Director. Fighting Hitler.” I paused and turned to face O’Donnell, who looked perplexed. I smiled politely and said, “Maybe I misheard him. I’m sorry I forgot about your son. Who is waiting in my office?” “Hashimoto Akihiko from Yokohama Specie Bank.” I nodded. O’Donnell handed me my schedule. When we arrived at my office, he bowed and scampered off down the hallway to his desk. I opened my office door and walked in. Hashimoto was already inside, sitting in a chair in front of my desk. When he saw me, he stood up and bowed. I returned a lower bow. “Mr. Hashimoto,” I said in Japanese. “What brings you to my office today?” Hashimoto was a tall and thin man in a dark suit. His hair was short and the skin was sallow around his face. He wore a pair of pince nez glasses that gleamed in the sunlight shining in from the window behind my desk. When I took my seat in front of him, he tightly grinned with artificial amicability. “Spare me pleasantries, Mr. Director. I think you know why I’m here.” Penney 19 I raised my eyebrows dramatically. “Is there some business that needs to be done between your bank and my company?” I was being careful with my words. Hashimoto did not really work for Yokohama Specie Bank. He was an agent for the Kempeitai in Australia. “The money that was transferred to your company’s accounts in Yokohama from Tokyo,” Hashimoto said. “You will transfer the money to associates on this list.” He pulled an envelope from his pocket and slid it across my desk. “Make sure that everyone on that list is provided with the proper funds. Make no mistakes.” I opened a desk drawer and put the envelope inside. Hashimoto watched every motion of my hand with a vigilant eye. “I will see that it’s done.” “It must be done by the end of the week,” Hashimoto ordered. “I understand you’ve taken your daughters out of school. You’ve drawn your window curtains at home and you keep your houselights off. Why?” “I don’t know what you’re talking about.” “You do. You look suspicious. You could ruin our entire enterprise and draw the ire of Tokyo. You are an important businessman, Tomimori-san. It would be disappointing if the Australian government thought you were up to something.” “I have a new driver.” “We know. We do not know him.” “What would you have me do?” “Return home to Kobe. Take your daughters with you. Say you will return after New Year’s.” Penney 20 “And then what?” Hashimoto adjusted his pince nez glasses on the bridge of his nose. “You are a dutiful servant of the empire. A man like you can always be useful.” “I see,” I muttered, shifting in my chair. “Transfer the money to the associates on that list,” Hashimoto said, standing up from his seat. “I will check back with you at the end of the week and make sure everything is in order. Make arrangements to visit your wife and youngest daughter in Kobe in the meanwhile. Make sure to bring your other two daughters home with you.” I stood up and bowed. Hashimoto returned the bow and left me alone in my office. When he was gone, I took my seat and withdrew the envelope from the desk drawer. I opened it with a letter opener. There was a list of thirty names. Each man listed was spread out throughout Australia, New Zealand, and other places across Asia and the Pacific. There were even some names from Singapore and Hawaii. Next to each name was the amount of money that the named person requested from Tokyo. They were agents working for the Kempeitai. I had been transferring money from Tokyo to agents since I became the director of Kanematsu’s Australian branch. I can’t remember how exactly I was enlisted, but I knew that it was expected from someone of my rank to do their duty to the empire. I did the work obediently and with little thought. My company was merely a middleman between the government and its agents. In return, I was often made privy to significant events that were about to unfold. I knew about the southern advance into Malaya. I did not know about Pearl Harbor. Very few people that worked at Kanematsu were complicit in the intelligence ring. It was, after all, my responsibility. Penney 21 Cooperating with the Kempeitai had never bothered me, although I was careful with how I handled them. The month’s events had left me shaken. As any Japanese, I was proud of my country’s overseas empire and our modernizing accomplishments in Korea, Manchuria, and China. But I never foresaw that we would go to war with the British and the Americans. I had been to India and the Philippines. I knew what those great empires were and what they could do. While the government in Tokyo might feel proud now as our Imperial Army and Navy spread throughout the region, I was not sure a war against two of the world’s greatest powers could be sustained. I worried about my family. I put the opened envelope and letter back inside the desk drawer and closed it. I opened up another drawer and pulled out a little brass singing bowl and hammer I had purchased in India a year before. I planned to give it to Seiko for her birthday. The bowl was clean and heavy and shone in the light. Setting the bowl on the desk, I weighed it in my mind. Its beauty distracted me from thoughts of business and war. Surly whatever happened to me or Japan, the bowl would last. It would last years without losing its luster, past my death and Seiko’s. I wondered where the bowl would be in one hundred years and whose hands it would be in. I wondered if they would appreciate the bowl’s splendor and what it meant and where it came from. I looked around my office, making sure I was alone. I picked up the hammer and tapped the bowl’s edge. The bowl rang faintly and, as it sang, I closed my eyes. Absorbing the vibration, I attuned myself to the stillness of the air around me. I breathed slowly and thought of memories that were not mine. Penney 22