The “Ins and Outs” of Practice Models in Child Welfare

advertisement

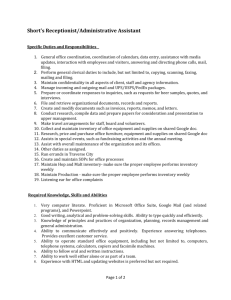

The “Practice” of Practice Models in Child Welfare Who We Are Anita P. Barbee, M.S.S.W., Ph.D. Professor University of Louisville Consultant, NRCOI and NCIC • • • • • • • • • • Kentucky Washington Florida New Hampshire New York City Kansas Oklahoma North Carolina Virginia Indiana Who We Are • Information service for the Children’s Bureau Christine Tappan • Experienced child Deputy Project Director welfare content and Child Welfare Information customer services Gateway team • Provide the information you need, when you need it www.childwelfare.gov Mission Promote the safety, permanency, and well-being of children, youth, and families by connecting professionals and the public to practical, timely, and essential information on: • • • • • • Programs Research Statistics Laws & policies Management & supervision Training resources Children’s Bureau’s Support of Practice Models Goals of Our Presentation • To be practical in how we share our experiences with you • To help you know how you can choose and create a Practice Model • To offer a roadmap to help you install and maintain a Practice Model Four Key Questions We will take you … • From “A” to “A” • Academic to Applied • Through our primary message, which is… • Be clear on what theories, values, and principles you want to guide practice • Make sure those theories, values, and principles are fully fleshed out across casework practice, the entire organization, and the system • Understand the complexity of implementing a Practice Model and the role that fidelity checking can have in installing and maintaining desired practice • Be clear on what the goals for your Practice Model are and what you want to accomplish before you begin the rollout “Start with the end in mind” Theory, research and evidence THE ACADEMIC LENS ON PRACTICE MODELS What Is a Practice Model? A practice model for casework management in child welfare should be theoretically and values based, as well as capable of being fully integrated into and supported by a child welfare system. The model should clearly articulate and operationalize specific casework skills and practices that child welfare workers must perform through all stages and aspects of child welfare casework in order to optimize the safety, permanency and well being of children who enter, move through and exit the child welfare system. Child Welfare Casework Practice Model Definition (Barbee, Christensen, Antle, Wandersman & Cahn, 2011) Keys to Intervention Success A theoretical base, including a theory of change A fully articulated set of actions and skills that can be observed for presence and strength System supports Evaluation results, including data benchmarks to monitor the efficacy of the model Wandersman (2009) Theory of Practice Delineates how to think about or conceptualize the practice with the population of focus. The theoretical foundation can respond to four areas: 1) The conceptualization of the problem (e.g., child maltreatment is embedded in the stage of a family’s life development) 2) The change theory that informs how that problem can be remediated (e.g., self-efficacy theory) 3) The theory that guides the critical contribution and influence of the relationship alliance or partnership (e.g., solution-focused theory) 4) The core practice values that underlie the approach to clients and the problem (e.g., family-centered or strengths-based) Integrated Framework from: Family Life Cycle Theory (Carter & McGoldrick, 1999) Cognitive Behavior Therapy Solution Focused Interviewing Family Life Cycle Theory Relapse Prevention (Cognitive Behavioral Theory) (Marlatt & Gordon, 1985; Pithers, 1990; Beck, 1993) Solution-Focused Therapy (Berg, 1994; DeShazer, 1988) All three models have their own well-documented evidence base. Justification Denial •Guilt and shame • Wild promises Triggering Events • Early Buildup • • • Negative thoughts “Poor me” Blaming others High Risk Situations for Abuse and Neglect Harmful Incident Late Buildup Physical abuse • Sexual abuse • Substance use • Lack of action • • Physical signs • Using fantasy • Building excuses What a Practice Model Is Not… • Simply a philosophy of practice or a series of philosophies or principles • Untethered from theory • A technique; thus, only focused on one piece of practice such as intake, assessments, or working with particular types of challenges • Executed without regard to organizational culture and climate Family-Centered, Strengths-Based, Culturally Competent Getting to Outcomes (GTO) • This framework is embedded in empowerment evaluation theory (Fetterman & Wandersman, 2005) and uses a social cognitive theory of behavioral change (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1977; Bandura, 2004). • It has the advantage of being a results-based accountability approach to change that has been used in smaller organizations to aid them in reaching desired outcomes for clients in such areas as preventing alcohol and substance abuse among teens as well as developing assets for youth (Fisher, et al., 2007) and preventing teen pregnancy (Lesesne et al., 2008). 1 8 GTO Effectiveness • Using a longitudinal, quasiexperimental design, Chinman et al. (2008) examined the impact of using GTO on (1) improvements in individual capacity to implement substance abuse interventions with fidelity and on (2) overall program performance in programs that did and did not utilize a GTO approach. • They found that the programs utilizing a GTO approach performed significantly better at both the individual and program levels than those that did not utilize the GTO approach. 1 9 Steps in GTO 1. 2. Identifying needs and resources Setting goals to meet the identified needs 3. Determining what science-based or evidence-based practices (EBPs) or evidence-informed practices or casework practice models exist to meet the needs 4. Assessing actions that need to be taken to ensure that the EBP fits the organizational or community context 5. Assessing what organizational capacities are needed to implement the practice or program 20 6. Creating and implementing a plan to develop organizational capacities in the current organizational and environmental context 7. Conducting a process evaluation to determine if the program is being implemented with fidelity 8. Conducting an outcome evaluation to determine if the program is working and producing the desired outcomes 9. Determining, through a continuous quality improvement (CQI) process, how the program can be improved 10. Taking steps to ensure sustainability of the program GTO Support System Model Tools + #2 Goals To Achieve Desired Outcomes #3 Best Practices Training + #4 Fit #1 Needs/ Resources Assessment Current Level of Capacity #5 Capacities = + #10 Sustain #6 Plan #9 Improve/ CQI QI/QA + #8 Outcome Evaluation #7 Implementation & Process Evaluation TA + Actual Outcomes Achieved GTO Steps 1-3: CHOOSING A PRACTICE MODEL GTO Steps 4-10: INSTALLATION OF A PRACTICE MODEL Assessing “Fit” and Capacity and Initiating Buy-in • In Step 4 of GTO, leadership support for the Practice Model (PM) is one of the first aspects of fit. In order to adopt a casework practice model, agency leadership must make a clear commitment to the model and express that commitment both inside the organization and outside with external community partners (e.g., Martin, et al., 2002). • In Step 5 of GTO, assessing organizational capacity for change and adoption of a PM is key. This includes identifying champions of change and engaging them to help build buy-in among staff and identify the resistors to change. Implementation Team Training & Coaching Establishing and Maintaining Fidelity • In Step 7 of GTO, part of the process or implementation evaluation should include creating and using several measures of fidelity, including: – A supervisor case consultation tool that guides discussion of practice on a regular basis, reinforcing key behaviors in the PM and serving as a measure to check implementation of the PM in daily work with children and families – An observational and case review measure to be used by a thirdparty evaluator to assess fidelity to the PM. The third-party evaluator could be: • The training evaluator to check on training transfer of PM skills covered in training • A coach checking on fidelity to help shape behavior to improve fidelity • Part of CQI or QA Evaluating PM Impact • In Step 8 of GTO, part of the outcome evaluation includes measuring and ensuring fidelity to the PM; otherwise, outcome effects can be attributed to other variables. • Build a chain of evidence by answering: – Does training of PM lead to attitude congruence with PM philosophy, values, and theories or attitude change? – Does training of PM lead to learning of concepts necessary to engage in the practices? – Do supervisors engage in case consultation and other training reinforcement behaviors to ensure fidelity to the PM? – Do coaches help staff practice with fidelity to the PM? – Do staff transfer what they learned in training about PM to field practice? – Do staff continue to improve and practice PM with fidelity? – Is there a link between adherence to PM and child outcomes? Role of Training and Evaluation in Workforce Development RECRUITMENT AND SELECTION People with best skills, abilities, values • B.S.W. students (e.g., PCWCP) • M.S.W. students (e.g., stipend) • Those with related degrees • Use of Realistic Job Previews (RJPs) • Use of resumes, interviews • Tests • Tasks TRAINING/TA SUPERVISION CQI/QA • Pre-Service • In class • Online • Field placement • In-Service • In class • Online • Reinforcement • On the job (OTJ) • Coaching and mentoring • Set expectations before training • Reinforce during & after training • Model/shadow • Observe • Coach/feedback • Educational supervision • Clinical supervision • SBC casework • Measure observable behaviors using behavioral anchor system while in learning mode to show progress • Conduct case reviews • Employee evaluation • Tie to organizational outcomes • Job performance • Retention • Tie to client outcomes • Safety, permanency, and well-being Using the CQI Process to Track and Ensure Fidelity • In Step 9 of GTO, fidelity measures should be incorporated into the CQI case review process to give additional feedback on individual fidelity and overall agency fidelity. • These data can be used to tie adherence to the PM with client outcomes, since both are measured in one tool. • The CQI/QA team can give feedback on training to enhance modules where practice in the field is weak. • The CQI/QA team can give feedback to leadership about the consequences of being slow in developing the infrastructure to support the PM. • The CQI/QA team can give feedback to supervisors about how their workers compare to State averages. • In Step 10 of GTO, sustainability can occur only if fidelity is maintained and outcomes affected; otherwise, there will be mutiny. Evaluation Research Seven major studies over 12 years • Study 1: Chart File Review (Martin, Barbee, Antle & Sar, 2002, Child Welfare) ─ To explore issues with implementation and short-term outcomes • Study 2: Qualitative Interviews With Workers and Clients ─ To explore client and worker experiences with the model (Antle, Christensen, Barbee, & Martin, 2008, Journal of Public Child Welfare) • Studies 3 & 4: Training Evaluation (Antle, Barbee, & van Zyl, 2008 Children and Youth Services Review; Antle, Sullivan, Barbee & Christensen, 2010 Child Welfare) ─ To identify the most effective strategies to promote transfer of the model Evaluation Research (continued) • Study 5: Management Data (van Zyl, Antle, & Barbee, 2010 chapter; Antle, Barbee, Sullivan, & Christensen, 2010, Children and Youth Services Review) ─ To examine the impact of general model use on safety, permanency, and well-being • Study 6: Continuous Quality Improvement Data (Antle, Christensen, van Zyl, & Barbee, 2012, Child Abuse and Neglect) ─ To examine the impact of specific model skills at various stages of the casework process on CFSR items and ASFA outcomes • Study 7: Particular practice behaviors that had the biggest impact on outcome achievement (van Zyl, Barbee, Antle & Christensen, in preparation) IMPACT OF SOLUTION BASED CASEWORK (SBC) ON CHILD WELFARE OUTCOMES Study 5: van Zyl, Antle, & Barbee, 2010, chapter; Antle, Barbee, Sullivan, & Christensen, 2010, Children and Youth Services Review Overview of Study Research Questions What is the impact of using SBC on child welfare outcomes of safety, permanency, and well-being? Sample Over 1,000 cases tracked for outcome data Design: Experimental-Control Pre-Post Experimental group received training in model Control group received NO training Data were collected 6 months post-training (and equivalent period for control group) and linked CFSR outcomes Procedure Outcome data on child safety, permanency, and well-being obtained through standardized State data reports and the Kentucky Foster Care Census Outcomes: Child Safety Positive impact of training on child safety. The SBC group had significantly fewer recidivism referrals for child maltreatment than the control group, F (2,112) = 18.63, p<.0001. SBC: n=350.00 Control: n=538.00 Outcomes: Permanency • There was no impact of training on permanency outcomes. • There is a significant negative correlation between number of placements and number of strengths identified, r (105) = -.199, p<.05. Outcomes: Well-Being There was a significantly longer period of time since the last dental visit for the control group than the training groups, t (30) = -18.45, p<.0001. SBC: x=1.53 Control: x=3.40 3.5 Number of Months 3 2.5 2 1.5 1 0.5 0 Time Since Visit with Parent Training Control There was a significantly longer period of time since the last visit with biological parents, t (30) = -5.48, p<.0001. SBC: x=1.17 Control: x=2.17 Summary of Study 5: Findings • Training had significant positive impact on child safety and well-being. ─ There were fewer recidivism referral reports for the SBC group. ─ The SBC group had more recent visits with biological parents and dental professionals. • There was no impact of training on permanency because training did not target these outcomes (although placement outcomes were significantly different in Study 1). • Limitations in research design led to the next study, through which implementation of specific elements of the SBC model were linked to Federal measures of outcomes. LINK BETWEEN MODEL AND CFSR OUTCOMES Study 6: Statewide Quality Assurance Data (Antle, Christensen, van Zyl, & Barbee, 2012, Child Abuse and Neglect) Overview of Study Research Questions • What is the relationship between SBC use and performance on CFSR items and outcomes? Sample • 4,559 cases over 4 years (2004-2008) Variables and Measurement • Solution Based Casework • Total, Intake/investigation, Case Planning, Case Management • Safety 1 and 2 • Permanency 1 and 2 • Well Being 1, 2, and 3 Procedure • CQI Review Process • Merged data across 4 years • Extracted SBC items from review tool • CFSR items and outcomes mapped onto CQI tool by CFSR/PIP team in KY SBC Items Intake/Investigation Is the documentation of the Sequence of Events thorough and rated correctly? Is the documentation of the Family Development Stages, including strengths, thorough and rated correctly? Is the documentation of the Family Choice of Discipline (including strengths) thorough and rated correctly? Is the documentation of Individual Adult Patterns of Behavior, including strengths, thorough and rated correctly? Is the documentation of Child/Youth Development (including strengths) thorough and rated correctly? Is the documentation of Family Support or Systems of Support, including strengths, thorough and rated correctly? Ongoing Same as above Was the parent involved when changes were made to any of the following: visitation plan, case plan, or placement? SBC Items Case Planning • Does the case plan reflect the needs identified in the assessment to protect family members and prevent maltreatment? • Were the individuals/family, child/ren, and foster parents/relatives/kinship caregivers engaged in the case planning and decision-making process? • Were noncustodial parents involved in the case planning process, if appropriate? • Were the community partners and/or others invited by the family engaged in the case planning process, or was there documentation that all efforts were made to engage the family in accepting community partners? • Are the primary Family Level Objective/s and Tasks appropriate and specific to the Maltreatment/Presenting Problem? • Have services been provided related to the primary Family Level Objective/s and Tasks? • Do the secondary Family Level Objective and Tasks address all well-being risk factors identified in the current CQA? • Have services been provided related to the secondary Family Level Objective and Tasks? • Are the Individual Level Objectives (ILO) based on the issues identified in the CQA? • Do the Individual(s) Level Objective and tasks address the perpetrator’s or status offender’s individual pattern of high-risk behavior? • Have services been provided related to the Individual Level Objective and Tasks? SBC Items Case Management • Is there documentation that the FSW has engaged the family and community partners in the decision-making process? • Is there ongoing documentation that comprehensive services were offered, provided, or arranged to reduce the overall risks to the children and family? • Is the progress or lack of progress toward achieving EACH objective (every FLO, ILO, and CYA objective) documented in contacts? • Is the need for continued comprehensive services documented at least monthly? • Has the SSW made home visits to both parents, including the noncustodial parent? • Did the SSW make the parental visits in the parents’ home, as defined by SOP 7E 3.3? • Prior to case closure, was an Aftercare Plan completed with the family/community partners? • Was the decision to close the case mutually agreed upon? Relationship Between SBC and Outcomes/Review Items There is a significant positive correlation between SBC scores (Total, Intake/Investigation, Ongoing, Case Planning, and Case Management) and all ASFA outcomes/CFSR items: The higher the SBC score (greater degree of implementation), the better were the safety, permanency, and well-being outcomes for each case. Impact of SBC on Compliance with Federal Standards for Safety There is a significant difference between high and low SBC groups for all Federal outcomes. There is a significant difference between high and low SBC groups for SAFETY 1, t (4,417)=-20.20, p<.0001. For SAFETY 1, the Federal goal was 83.7%. The mean % for the low SBC group was 76.50%, and the mean % for the high SBC group was 89.98% (exceeding the Federal standard). There is a significant difference between high and low SBC groups for SAFETY 2, t (4,405)=-23.40, p<.0001. For SAFETY 2, the Federal goal was 89%. The mean % for the low SBC group was 80.66%, and the mean % for the high SBC group was 95.53%. Impact of SBC on Compliance With Federal Standards for Permanency There is a significant difference between high and low SBC groups for PERMANENCY 1, t (3,513)=-24.62, p<.0001. For PERMANENCY 1, the Federal goal was 32%. The mean % for the low SBC group was 70.07%, and the mean % for the high SBC group was 92.72%. There is a significant difference between high and low SBC groups for PERMANENCY 2, t (1,533)=-14.54, p<.0001. For PERMANENCY 2, the Federal goal was 74%. The mean for the low SBC group was 66.89%, and the mean for the high SBC group was 89.57%. Impact of SBC on Well-Being There is a significant difference between high and low SBC groups for WELL-BEING 1, t (4,336)=-35.22,p<.0001. For WELL-BEING 1, the Federal goal was 67%. The mean for the low SBC group was 66.01%, and the mean for the high SBC group was 94.29%. 100.00% 90.00% 80.00% 70.00% There is a significant difference between high and low SBC groups for WELL-BEING 2, t (2,988)=-19.5, p<.0001. For WELL-BEING 2, the High SBC Federal goal was not established in the reports. The mean for the low SBC group was 61.59%, Federal and the mean for the high SBC group was Standard 90.58%. Low SBC 60.00% 50.00% 40.00% 30.00% 20.00% 10.00% 0.00% Well Well Well Being 1 Being 2 Being 3 There is a significant difference between high and low SBC groups for WELL-BEING 3, t (3,467)=-23.93,p<.0001. For WELL-BEING 3, the federal goal was 78%. The mean for the low SBC group was 60.38%, and the mean for the high SBC group was 88.81%. Summary of Study 6 Use of the SBC model is associated with significantly better scores on all 23 CFSR review items and the 7 outcomes of safety, permanency, and well-being. There are differential effects of SBC on outcomes based upon the stage of the case: The most critical points in a case for SBC use to promote safety outcomes are in the intake/investigation stages. The most critical points in a case for SBC use to promote permanency outcomes are in case management and case planning. The use of SBC during case planning, case management, and ongoing stages is important for well-being outcomes. The SBC scales account for very high percentages of the variance in these outcomes. Higher degree of use of the SBC model (across all stages of the case) results in exceeding Federal standards for each of the key outcomes of safety, permanency, and well-being. When the model is not used or used to a lesser degree, cases fail to meet these Federal standards for most outcomes. Practical, pragmatic, and poignant THE APPLIED SIDE OF PRACTICE MODELS Choosing and Installing a Practice Model • • • • • Kentucky Washington Florida New York City Kansas • New Hampshire NH’s Experience • Benefits of a Practice Model • Reasons to Create a Practice Model • Key Components of a Practice Model – Theoretical Framework – Core Values & Practice Principles – Casework Components – Practice Elements and Behaviors – Organization and System Standards Benefits • Promotes alignment – Statewide consistency in families’ experiences with child welfare – With Juvenile Justice – With Stakeholders • Addresses all aspects of the agency – Systemwide undertaking • Guides daily interactions without prescribing a specific program – “Super” clarity and articulation of beliefs and principles • Describes behaviors, activities, and strategies in significant detail – Sets the expectation for quality – a higher bar • Defines outcomes – Aligned with CFSR, CFSP/APSR • Address “initiative” fatigue – Creating a Practice Model MUST BE different “This is not a new initiative…it will be our way of life” Maggie Bishop, NH DCYF Director, May 2009 40 Reasons to Do a Practice Model • • • • Reform Legal mandates Improvement effort Address an identified problem • Proactive leadership • Something was missing • Go from good to great “New Hampshire’s Practice Model outlines the Division for Children, Youth and Families’ beliefs and guiding principles and creates a framework for decision making and a practice structure to guide work within all levels of the agency. The Practice Model does not dictate what our jobs are, rather it influences the way individuals do their jobs. It serves as a foundation designed to inspire the Divisions’ work and keep the focus on providing services that are consistent. Furthermore, this impact reaches far beyond the limits of DCYF. It extends to influence the work that is done by providers and others who offer services for children, youth, and families throughout the State of New Hampshire.” NH Practice Model Design Team February 2010 Beliefs and Guiding Principles Prevention reduces child abuse and neglect. All children/youth should be safe. Everyone deserves to be treated with courtesy and respect. All children/youth need and deserve permanency. All children, youth, and families deserve a life of well-being. All families have strengths. Theoretical Framework “New Hampshire has based our Practice Model on four theories. These theories are anchors that ground our Practice Model in a research-based framework. These theories are: • Family Development Theory • Solution Focused Theory • Restorative Justice Theory • Parallel Process Theory” NH Implementation Team, December 2010 Bringing It All Together • Casework Components • Practice Elements Family Engagement Toolkit Structured DecisionMaking Parent Partners SBC Family Meetings Youth Action Pool Trauma Informed Organization and System Standards Organizational Development Systemic alignment •Becoming a learning organization •Viewing training as a system intervention •Developing the capacity for change • Assessing and measuring organizational readiness •Adjusting supervisory standards •Using Appreciative Inquiry to strengthen capacity •Modifying organizational and practice policies and standards •Assessing workforce development approaches •Considering the impact on Information Technology •Reassessing budget priorities •Clarifying impact on contracting for services •Progressing to Continuous Quality Improvement Exploration & Installation Leadership Cross-functional project team Communication Resources Implementation Leadership Communication Cross-functional team Resources Coaching Sustainability Implementation plus Sustained Coaching Communication & “Ownership” Culture & climate monitoring Support & Resources Frequent monitoring and evaluation • • • • • • • • Sustainability starts from day 1 Leadership must live the Practice Model Practice Model can generate organizational credibility Creating a culture of learning is key Practice Model = PIP = Practice Model Communication: the Practice Model becomes the language of the system Time is a friend and a foe Culture and climate need constant, careful, and inspirational attention GETTING AND MAINTAINING BUY-IN • • • • • • • Transparency Feedback loops More is better Use varying approaches Go to the people Demonstrate passion! Youth, parents, and staff tell the story best • Partnerships are critical to success 6 3 Establish a strong infrastructure Cross-Functional Project Teams Communication Team Members & roles defined Evaluation Team Policy Team Training Workgroup Sustainability linkages identified from the beginning Project Team Design Team 6 4 5 Approach to Practice Model design Staff from across the agency Application and selection Monthly work sessions and homework in between Commitment to a decisionmaking process “Spread” leaders Sustained engagement Youth and parent team members 6 7 MAINTAINING FIDELITY Impact Practice Model = Program Improvement Plan = Practice Model Identified PIP target areas and matched PM strategies • Safety and assessment • Family engagement • Culture and climate Most significant gains Child and Family Well-Being Outcome 1: Families have enhanced capacity to provide for their children’s needs. • Item 17: Needs and Services of Child, Parents, and Foster Parents • Item 18: Child and Family Involvement in Case Planning • Tem 20: Caseworker visits with parents (s) Safety Outcome 2: Children are safely maintained in their homes whenever possible and appropriate. • Item 3: Services to Family to Protect Child(ren) in the Home and Prevent Removal or Re-entry Into Foster Care • Item 4: Risk Assessment and Safety Management More effective together… References Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (1977). Attitude–behavior relations: A theoretical analysis and review of empirical research. Psychological Bulletin, 84, 888-918. Antle, B. F., Barbee, A. P., Christensen, D. N., & Sullivan, D. (2010). The prevention of child maltreatment recidivism through the Solution-Based Casework model of child welfare practice. Children and Youth Services Review, 31, 1346-1351. Antle, B. F., Barbee, A. P., Sullivan, D. J., & Christensen, D. N. (2008). The effects of training reinforcement on training transfer. Child Welfare, 88, 5-26. Antle, B. F., Barbee, A. P., & van Zyl, M. A. (2008). A comprehensive model for child welfare training evaluation. Children and Youth Services Review, 30, 1063-1080. Antle, B. F., Christensen, D., Barbee, A. P., & Martin, M. (2008). Solution-based casework: A p paradigm shift to effective, strengths-based practice for child protection. Journal of Public Child Welfare, 2, 197-227. Antle, B. F., Christensen, D. J., van Zyl, M.A., & Barbee, A. P. (2012). The impact of the solution based casework (SBC) practice model on federal outcomes in public child welfare. Child Abuse and Neglect, 36, 342-353. References Bandura, A. (2004). Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Education & Behavior, 31, 143164. Barbee, A. P., Christensen, D., Antle, B. F., Wandersman, A., Cahn, K. (2011). System, organizational, team and individual changes that need to accompany adoption and implementation of a comprehensive practice model into a public child welfare agency. Children and Youth Services Review, 33, 622-633. Chinman, M., Hunter, S. B., Ebener, P., Paddock, S. M., Stillman, L., Imm, P., & Wandersman, A. (2008). The Getting to Outcomes demonstration and evaluation: An illustration of the prevention support system. American Journal of Community Psychology, 41, 206-224. Christensen, D. N., Todahl, J., & Barrett, W. G. (1999). Solution-based casework: An introduction to clinical and case management skills in casework practice. New York: Aldine DeGruyter. Fetterman, D. M., & Wandersman, A. (2005). Empowerment evaluation principles in practice. New York: Guilford Press. References Fisher, D., Imm, P., Chinman, M., & Wandersman, A. (2007). Getting to outcomes with developmental assets: Ten steps to measuring success in youth programs and communities. Minneapolis: Search Institute. Lesesne, C. A., Lewis, K. M., White, C. P., Green, D. C, Duffy, J. L., & Wandersman, A. (2008). Promoting science-based approaches to teen pregnancy prevention: Proactively engaging the three systems of the interactive systems framework. American Journal of Community Psychology, 41, 379-392. Martin, M. H., Barbee, A. P., Antle, B., Sar, B., & Hanna, S. (2002). Expedited Permanency planning: Evaluation of the Kentucky Adoptions Opportunities Project (KAOP). Child Welfare: Special Issue on Permanency Planning, 81, 203-224. van Zyl, M. A., Antle, B. F., & Barbee, A. P. (2010). Organizational change in child welfare agencies. In S. Fogel, & M. Roberts-DeGennero (Eds.), Empirically supported interventions for community and organizational change. New York: Lyceum Books. Wandersman, A. (2009). Four keys to success (theory, implementation, evaluation, and resource/system support): High hopes and challenges in participation. American Journal of Community Psychology, 43, 3-21.