The Military Chieftain Ever since 1800, Thomas Jefferson's

advertisement

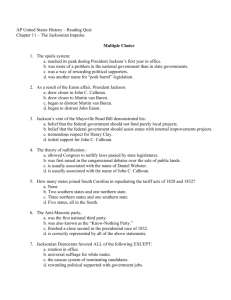

The Military Chieftain Ever since 1800, Thomas Jefferson’s Republicans had held a locked grip on the presidency. In fact, after the Federalists had committed political suicide in convening the Hartford Convention in the midst of the War of 1812, the Republicans had been virtually the only functioning political party with anybody to elect. The election of 1824 represented a break in the normal presidential nominating process. As the reigning political organization, the Republicans chose their candidates by caucus. The president usually sent in the name of his secretary of state as his successor. Under this plan, in 1824, James Monroe would nominate John Quincy Adams. The expansion of voting rights forced a change in this process in 1824. The caucus system seemed like an insider process. Divisions had grown up within the Republicans, with the National Republicans and the Democratic-Republicans sponsoring differing agendas. The likelihood of Adams’s succession to the nomination became clouded. Although he had substantial experience as a diplomat, he still resembled a Federalist. His father was the Federalists’ last president. He espoused the National Republican agenda. Adams had a challenger in Henry Clay. Clay represented the interests of the West. He was the Speaker of the House of Representatives and was in a position to obstruct an Adams nomination. He was also becoming the exponent of the “American System.” Republican Party regulars used the caucus to nominate William Crawford. Clay arranged for a rival nomination by the Kentucky legislature. Adams arranged for a counter-nomination by New England and New York. The split made it likely that the election would be thrown into the House of Representatives, where Clay was confident of victory. Clay had reckoned without the popular emergence of Andrew Jackson. Andrew Jackson had become the favorite of Western Republicans and an enemy of the National Republican agenda. He was a selfmade lawyer who rose to prominence and wealth in Tennessee. He was possessed of a volcanic temper and given to dueling. He established a reputation as a ruthless Indian fighter. He won the War of 1812’s greatest victory at New Orleans. He nearly triggered war with Great Britain again in 1818 by hanging two British subjects and occupying Florida. The Panic of 1819 pushed Jackson back into politics. He was an enemy of the banks. He was more of a Democrat than a classical Republican. Jackson became the favorite candidate of Republicans who liked neither Clay nor Adams. The Tennessee legislature nominated Jackson. In 1824, Jackson swept the popular vote but failed to garner sufficient electoral votes to beat Clay, Adams, and Crawford. 1. Did Clay have good reason to believe he could defeat Adams? 2. What made Jackson so much more attractive politically to American voters than Clay or Adams, with their wide experience in national government? The Politics of Distrust Clay was fairly certain that he would probably not win a majority of electoral votes the first time around. He was certain, however, that once the election was thrown into the House of Representatives, where he was, of course, the Speaker of the House, well, that was about as good as throwing it into his own lap. The stalled election of 1824 was thrown into the House of Representatives. Although Clay finished fourth in electoral votes, he used his position as Speaker of the House to recruit votes. Clay was rumored to have struck a corrupt bargain with Adams to permit an Adams election, after which Clay would become secretary of state. Adams was elected on the first ballot. The corrupt bargain besmirched the reputations of both Adams and Clay. Adams tried to prove his innocence by including Jackson’s supporters in his administration, only to have them sabotage it. Adams got no support for implementing the National Republican economic agenda. Jackson gathered his forces for the election of 1828. Jackson won an overwhelming victory, especially among new voters. He was supported by an alliance of anti-tax, anti-bank, and anti- corporate farmers and workers. Ironically, Jackson himself was a slaveholder and a wealthy man. But Jackson appeared as the enemy of great concentrations of power and the friend of territorial expansion. The election of 1828 marked a shift from republican politics to democratic politics. Democracy was the answer to distrust. In contrast to the private swearing-in ceremonies of previous presidents, thousands flooded unbidden into Washington. Jackson’s inaugural reception resembled a democratic bacchanal. Jackson instituted an internal administrative revolution. Nearly 1,000 officers, from the cabinet down to postmasters, were turned out. They were replaced by Jackson’s personal friends: Martin Van Buren, Samuel Ingham, John H. Eaton. Jackson insisted on conducting the appointment process by the spoils system. While Jackson worked to promote agricultural interests, he fought government support for manufacturing and commerce, although he allowed neither to threaten the permanence of the federal union. Jackson used his veto to strike down a number of congressionally funded projects. He vetoed the Maysville Road project. He signed a tariff bill in 1832, but only with the understanding that it would be used to permanently eliminate the national debt. Southern interests were aghast at Jackson’s approval of the tariff. John Calhoun wrote two major protests advocating state nullification of the tariff. Calhoun delegated defense of nullification in the Senate to Robert Hayne, who was out-argued by Daniel Webster. Calhoun failed to enlist Jackson’s endorsement of nullification at the 1830 Jefferson’s birthday dinner. Calhoun prompted South Carolina to challenge the tariff by nullifying it within state boundaries, only to be forced by Jackson to back down. 1. Was Calhoun or Jackson more attuned to the ideas of Thomas Jefferson? 2. How did Jackson align his promotion of southern interests with his hostility to South Carolina and nullification? The Monster Bank In times of prosperity, the demand for specie could keep banks from overextending themselves through excessive loans and excessive issues of paper currency. In harder economic times, the Bank of the United States could ease the strain by relaxing its demands for specie from the local banks. The Second Bank of the United States (BUS) had been the prime symbol of National Republicanism ever since its original chartering in 1816. It served to regulate the national money supply. All federal customs duties and taxes were payable to the BUS. It could demand repayment for bank notes from the original issuers in specie. This power restrained banks from overextending themselves by overprinting bank notes. The BUS provided resources for national investment. As a mixed public/private corporation, it could put government economic clout behind private enterprises. The constant inflow of government revenues gave it constant liquidity and vast financial reserves. The BUS could step in to fund development projects that Congress could not. The power of the BUS outraged Democratic-Republicans. The BUS did nothing to allay these suspicions. Its first president, William Jones, helped trigger the Panic of 1819. Its second president, Nicholas Biddle, used the BUS’s resources to protect the BUS politically. Jackson would have moved more dramatically against the bank in his first term but didn’t. He was restrained by other political problems, and the BUS had a 20- year charter. Biddle actually provoked a confrontation by appealing to Congress in 1832 for an early rechartering. Henry Clay advised in favor of rechartering. It would pass Congress without difficulty. If Jackson vetoed it, the veto would be overridden by Congress and alarm the electorate. If Jackson signed it, it would destroy his reputation with his own party. A rechartering petition was submitted by Clay in 1832. Jackson vetoed it. Accompanying the veto was a veto message that identified the BUS’s supporters as foreigners, financiers, and usurpers. The veto message was instantly popular. Clay called for an override of the veto. He warned of dire financial consequences if the BUS was shut down. Jackson’s logic in the veto was identical with nullification. However, the veto was not overridden. When Clay attempted to make the BUS an issue in the 1832 election, he was soundly defeated by Jackson. The veto inaugurated a bank war. The BUS still had four more years to run on its charter. Jackson went on the offensive and removed government deposits from the BUS. Two successive treasury secretaries refused to obey Jackson’s order. Finally, Jackson recruited Roger Taney to remove the deposits. Government funds were now deposited in seven “pet” state banks. The redeposit led Clay to ask Congress for a motion of censure against Jackson. Biddle retaliated by calling in loans. The result was a major financial panic in 1837. Jackson eventually increased the number of pet banks to more than 300. He used the pet banks to pay off the national debt. He parceled out government revenue surpluses to the states. He issued a Specie Circular, which required that payment for federal lands be made only in specie, thus nudging the country away from the use of bank notes. The bank war left Jackson with an even more secure grip on power. The BUS was reduced to seeking a state charter from Pennsylvania to keep operating. Jackson rewarded Taney by making him chief justice after the death of John Marshall. 1. What aspects of the economy were most likely to be hit by Jackson’s veto of the BUS charter? 2. Why was destroying the “monster bank” essential to Jackson’s political vision?