Wind Turbine Noise - Department of Environment and Local

advertisement

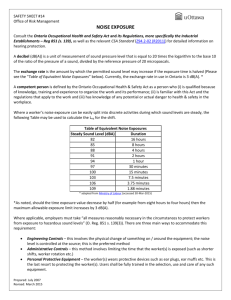

Date: 20th Feb 2013 Killucan- Raharney Wind Information Group Co. Westmeath Planning Section Department of the Environment, Community and Local Government Custom House Dublin 1 Email: windsubmissions@environ.ie Dear Sir/Madam, Killucan-Raharney Wind Information Group represents a community of very concerned citizens in Westmeath. The community is specifically concerned with the unprecedented rush to develop Industrial scale Wind Energy development through our community. The present (2006) guidelines facilitate Industrial-scale wind development through our rural residential area, in close proximity (500m) to people’s homes and we will not accept this irresponsible approach. Evidence of the facilitation of these proposed wind developments through our community is in the form of the 100’s of local landowners/farmers who have signed binding option contracts with Wind Energy companies, initially without community knowledge and consultation and subsequently against the stated wishes of 90% of our community. We wish to make the following submission to the Department of the Environment, Community and Local Government on the Wind Energy Development Guidelines 2006 Focused Review and the current Draft of the Statutory Wind Energy Development Guidelines (WEDG). 1. Overview of the WEDG Focused Review Due to the failure of the State to consult appropriately with the public, I was until Q2 2013, unaware of both the Focused Review of the Wind Energy Guidelines 2006 and the National Policy and plans for wind farms nationally and in the Midlands Region. As a consequence, in February 2013 I was prejudiced from making an informed submission and was in effect excluded from phase 1 of this review. The short period given for Phase 1 Submissions (31st January 2013 to 15th February 2013, or 10 working days) was wholly inadequate and further prejudiced the Public’s rights under the Public Consultation (Aarhus Convention) Directive. It is apparent from the above that the intention by the Government was to keep the Public uninformed and excluded from the process, and the right to adequate time to make researched and evidenced based submissions was entirely suppressed. With respect to the scope of the WEDG Review it too should have been subjected to public consultation. In this regard I note the position of the Irish Planning Institute which states; “these technical guidelines cannot take key strategic issues on the future location of renewable energy projects into account” and it called for “a national strategy for wind energy alongside a national landscape strategy”. In addition to the process and scope, what is of equal concern is that those evidence based submissions which were made by the public, such as those made by CREWE and independent 1|Page experts including the world leading Acoustician Dick Bowdler, and indeed by the State (the Deputy Chief Medical Officer) have been entirely ignored by the Government in the current draft. It is of concern that these submissions were not published, particularly given the lack of public confidence in the SEAI’s oversight of the guideline review process. The lack of transparency in relation to the formulation of the draft WEDG is compounded by the failure to include the Best Practice Guidance to be contained in Appendix 1. It is also deeply regrettable that the Department has considered it appropriate to consider only 3 aspects of the Guidelines, while there are firm proposals in place to develop 28,000MW and beyond, of wind-derived electricity in Ireland over coming years. This corresponds to almost 10,000 turbines (at 3MW capacity). The current level of turbines installed in Ireland at this point in time is approximately 1000. The entire Guideline as it currently stands, promotes irresponsible on-shore Wind development. It should, at the very least, set out up front, in a very transparent manner, the costbenefit analysis for wind-derived electricity; this analysis requires a clear and honest evaluation of the net impact on Carbon emissions, as a result of wind development, taking a 15 year usage horizon into account. The revised Guideline states that it “seeks to achieve a balance between the protection of residential amenity of neighbouring communities in the vicinity of wind energy developments, and facilitate the meeting of national renewable energy targets”. It is my view, thus far, that the balance is firmly in favour of the developments and significantly removed from community concerns. Significant mistrust of Government Departments (Environment & Energy in particular) has been created through the review process to date, in relation to Wind Energy Guidelines, initially by the extremely short initial consultation window, secondly through the narrow focus of the review, thirdly through the disingenuous approach to noise limit changes and finally through the unstated, but apparently obvious, approach to facilitate relatively unlimited Wind Energy Development without consideration for communities, environment or cost. 2. Wind Turbine Noise Noise is not simply an “unwanted sound”. As the UK Health Protection Agency has highlighted: “noise is sound that is perceived as unwanted, annoying or disturbing.”1 Contrary to the assertion in the draft WEDG “that given the ‘unwanted’ component it can have a strong subjective aspect” there is a wealth of evidence outlining the noise characteristics, social and environmental factors that contribute to the perception of sound as noise, with obvious implications for human health.2 1 UK Health Protection Agency, Environmental Noise and Health in the UK (2010). See, for example, World Health Organization, Guidelines for Community Noise (1999); Stansfeld and Matheson, Noise pollution: non-auditory effects on health (British Medical Bulletin); National Academy of Engineering of the National Academies, Committee on Technology for a Quieter America, Technology for a Quieter America (Washington DC, 2010); van den Berg, “Effects of wind turbine noise on people” in Bowdler 2 2|Page This issue was addressed by the Department of Health’s Deputy Chief Medical Officer in her response to the Department’s request for feedback on the targeted review of WEDG06, with specific reference to the risk that industrial wind turbines pose for certain people. The Draft WEDG must take account of the Deputy Chief Medical Officer’s advice given by the Department of Health in relation to the: “consistent cluster of symptoms related to wind turbine syndrome which occurs in a number of people in the vicinity of industrial wind turbines. There are specific risk factors for this syndrome and people with these risk factors experience symptoms.” • It is submitted that given this assessment by one of the State’s chief public health experts, it is critical that the Draft WEDG take seriously the objective health effects of wind turbines rather than treating people’s response to wind turbine noise as a subjective reaction to unwanted noise. The Marshall Day Report highlighted the need to deal with the following special audible characteristics of wind turbine noise3, including: Amplitude modulation Impulsiveness Infrasound Low frequency noise Tonality It is of significant concern that though the Minister purports to take an evidence approach to the WEDG Review, they have ignored an evidenced approach where their experts have suggested same. • It is imperative that the WEDG Review includes an evidenced based approach to dealing with Amplitude modulation, Impulsiveness, Infrasound, Low frequency noise and Tonality as recommended by Marshall Day. Furthermore, the failure to include the Best Practice Guidance to be contained in Appendix 1 reflects the inadequacy of the Draft WEDG and prompts the need for a further round of public consultation to determine the public response to the environmental protection measures proposed in this guidance. 3. Noise – insignificant exceedance of existing levels at homes In terms of noise assessment, best practice on the assessment of noise requires consideration of the following issues: Sensitivity of location (e.g. existing land uses, Noise Management Areas, Quiet Areas); and Leventhall (eds) Wind Turbine Noise: How it is produced, propagated, measured and received (MultiScience Publishing Co. Ltd, 2011); Driscoll, Stewart and Anderson “Community Noise” in Berger (ed) The Noise Manual (American Industrial Hygiene Association, 2003), pp.602-636; and Fields “Effect of personal and situational variables on noise annoyance in residential areas” (1993) 93(5) Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, pp.2753-2763. 3 Marshall Day, SEAI Report, p.111. 3|Page Existing noise level and predicted change in noise level; Character (tonal, impulsivity etc), duration, the number of occurrences and time of day of the noise that is likely to be generated; Absolute level and possible dose-response relationships e.g. health effects. The draft WEDG propose an absolute limit for wind turbine noise. While this approach does offer some clarity on the maximum acceptable level of wind turbine noise, the application of a ‘one size fits all’ limit to all environments, including Quiet Areas, without consideration of background noise levels, is in conflict with the objectives of the EIA Directive, which are to protect both the environment and the quality of life of individuals. The proposed application of an absolute noise limit for wind turbine noise, irrespective of background noise levels, is also in conflict with the EPA Guidelines on the Information to be Contained in Environmental Impact Statements (2002).4 These statutory guidelines set: “statutory criteria for the presentation of the characteristics of potential impacts” These include an assessment of the magnitude and complexity of the impact of any development (p.23) including in the case of threshold wind farms, noise. It is internationally accepted that an increase of 5dB in background noise levels arising from any development is significant and may have the potential to have a substantial adverse impact.5 It is worth noting that in the case of Strategic Infrastructure, such as the proposed DART underground project, the following comment was made in relation to noise impact:6 “The emphasis – at night – should be mainly on the pre-existing ambient levels outside people’s bedrooms. Internal noise ambient levels, at night, in many houses, both rural and suburban around Dublin are of the order of 18-25LA90, and even in daytime are not much higher. External levels of 32-35 LA90 are commonplace, in calm weather. Since the proposed fixed plant will operate for many years to come, it is very important that the noise due to the plant does not cause undue discomfort or any significant sleep disturbance. It is clear that due cognisance is to be taken of the existing ambient noise levels and that the increase in this is to be minimised. Our recommendation is that a maximum increase of 3dBA, on the lowest reoccurring LA90 5mins, should be the objective.” [emphasis added] The draft WEDG fail to take due account of existing ambient noise levels. This inconsistency in approach in relation to wind energy projects, by contrast with comparable projects such as the DART underground project, must be addressed if a balance is to be achieved between protection of residential amenity and facilitating national renewable energy targets. The assertion of the draft Guidelines that “Generally the reduction in noise levels between the outside of a dwelling and the inside would be approximately 10dBA or more” needs to be evaluated 4 Available at http://www.epa.ie/pubs/advice/ea/guidelines/epa_guidelines_eis_2002.pdf. Tecnhical Advice Note Assessment of Noise, available at http://www.scotland.gov.uk/Resource/Doc/343341/0114220.pdf. 6 A study of the Airborne Noise Aspects of the Proposed Dart Underground Railway Development, available at www.pleanala.ie/news/NA0005/Inspector's_Report.pdf. 5 4|Page on a case by case basis i.e. each and every home with 2km of turbines greater 50m in height, as part of the EIS. This is critical as homes of differing manufacturing material specifications and ages will allow more of less outside noise penetrate the home. In addition, due consideration must be given to homes where the residents prefer to sleep with bedroom windows open. • It is submitted that the WEDG Review must take account of existing background noise levels (to include character, magnitude and complexity) and sensitivity of locations (sensitive receptors and Quiet areas) and in accordance with comparable projects such as the DART underground, set “a maximum increase of 3dBA, on the lowest reoccurring LA90 5mins”. Under no circumstances should the “substantial adverse impact” threshold of a 5dB (or greater) increase in background noise be permitted. It is also submitted that background noise measurements must also be taken inside homes, in the event that the building fabrics of particular homes do not reduce noise limits by 10dB and /or where the residents wish to sleep during summer months with bedroom windows open. 4. Noise Sensitive Properties & “Quiet Areas” The omission of commercial premises from the definition of noise sensitive properties in the draft WEDG needs to be addressed. In terms of areas of special amenity value, the 2002 END Directive 2002/49/EC requires measures to be put in place to protect the amenity value of Quiet Areas in Open Country. These areas, identified in the EPA and SWS Noise in Quiet Areas Report (2000),7 have not been considered in the draft WEDG. This EPA report titled; “Environmental RTDI Programme 2000–2006 ENVIRONMENTAL QUALITY OBJECTIVES, Noise in Quiet Areas” was undertaken to comply with the Environmental Noise Directive. The Executive Summary identifies the status of this report: “The European Commission has adopted a Directive relating to the Assessment and Management of Environmental Noise (EU, 2002). Member States, including Ireland, are required to implement the Directive and to adopt action plans to meet its objective. The purpose of the directive is to protect the quality of our acoustic environment, control and manage environmental noise in built-up areas, in public parks or other acoustically valued soundscapes (Quiet Areas) in an agglomeration and in Quiet Areas in open country. Establishing the location and determining the quality of Quiet Areas is the first step towards implementation of this directive. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in association with SWS Environmental Services developed this research project to meet the requirements of this directive … The information produced by the project will make a significant contribution to the implementation of the Environmental Noise Directive and will greatly assist Ireland and other Member States in introducing accountable noise abatement development programmes and related monitoring systems for reducing and managing noise pollution.” (pg. vii – Executive Summary) (emphasis added) “This research provided comprehensive baseline data for Quiet Areas (as defined in the proposed EU Environmental Noise Directive) throughout Ireland.” (pg. 11) 7 http://www.epa.ie/pubs/reports/research/land/EPA_noise_in_quiet_areas_ERTDI17_synthesis.pdf 5|Page The EPA Environmental RTDI Programme identifies the base line data and location of “Quiet Areas” throughout Ireland together with mapping of Quiet Areas which included “in excess of 170,000 environmental measurements.” (“RQA”): The EPA Environmental RTDI Programme defines the Environmental Quality Objectives for how “Quiet Areas” are to be protected in Ireland to comply with the EU Noise Directive: “The noise from anthropogenic sources should not be clearly audible at any point within Quiet Areas and the noise levels when measured in wind speeds of less than 2 m/s in the absence of significant environmental (geophonic or biophonic) sounds, should not exceed an LA90,1h of 30 dB by day or an LA90,1h of 27 dB by night. (The natural baseline sound level is regarded as the LA90,1h in the absence of anthropogenic noise.” (pg. 20) (emphasis added) “Considering that the Directive defines a Quiet Area in open country as an area that is undisturbed by noise from traffic, industry or recreational activities, it is proposed to define a Quiet Area as an area in open country, substantially unaffected by anthropogenic noise. The overall objective should, 6|Page therefore, be set in such a way as to prevent the degradation of the acoustic quality by the sources of noise listed.” (pg. 17: Environmental Quality Objectives) (emphasis added) For the avoidance of doubt, Wind Farm noise is one of the six anthropogenic noise types listed by the EPA. (pg 13, 6.1). The Draft WEDG has entirely ignored the protection of Quiet Areas, and the overarching Environmental Noise Directive. • It is imperative that the WEDG Review provides the protection specified by the EPA pursuant the Environmental Noise Directive for Quiet Areas, and that anthropogenic wind farm noise “should not exceed an LA90, 1h of 30 dB by day or an LA90, 1h of 27 dB by night” so as “to prevent the degradation of the acoustic quality”. The EPA identifies the appropriate noise measurement indicator for both environmental background noise and anthropogenic wind farm noise and specify assessment is required: “Where natural environmental sounds dominate, the LA90 is a very good indicator, while the LAeq is a good indicator when quantifying anthropogenic noise.” (pg. 19). (emphasis added) “Approval for any proposed development related to commercial or industrial activity or transportation, within or within such distance of a Quiet Area(s) as would be likely to be audible should be subject to the production of an impact statement of noise within the Quiet Area(s) from the development.” (pg. 19) “Where an impact statement of noise is to be produced, noise modelling and prediction of noise levels should be undertaken to illustrate the impact of noise levels within the Quiet Area(s) using appropriate GIS/noise-modelling methodologies.” • It is imperative that the WEDG Review uses the appropriate LAeq Noise measurement for anthropogenic Wind Farm noise as specified by the EPA Environmental RTDI Programme pursuant to the Environmental Noise Directive. It is submitted that evidence based assessment (Noise Impact Statement) together with noise modelling must be undertaken as part of an application which illustrates in accordance with the Directive that Quiet Areas will not degraded. The EPA Environmental RTDI Programme identifies that protection of Quiet Areas under the Environmental Noise Directive should be integrated with other EU Directives and that Quiet Areas should also be protected in conjunction with sites of inter alia, national, regional, local, heritage and cultural importance and environmentally sensitive areas: “Implementation of the Environmental Noise Directive and the identification and management of Quiet Areas should be integrated with other relevant EU Directives such as the Habitats and Birds Directives.” (pg. 17) “Criteria for selection and identification of Quiet Areas should be linked with sites of national, regional or local importance with regard to landscape, cultural or historical sites, amenity areas or environmentally sensitive areas such as RAMSAR or SPA.” (pg. 17) 7|Page There is a non-coincidental, direct correlation between the EPA Quiet Areas and those areas which are rich in Biodiversity and recorded EU protected species. Westmeath has significant sites of National, Regional, and Local importance. For example, the Ancient Royal site “The Hill of Uisneach” and it’s integral surrounding landscape has been submitted by the State in 2010 for Unesco World Heritage Site Status: “The Hill of Uisneach” is an ancient ceremonial site of National importance and renown (National Monument Number 155) which, in Irish mythology was the centre of Ireland. Such is the importance of this site, that along with Cashel, Dún Ailinne, the Rathcroghan Complex, and the Tara Complex, it was submitted by Ireland as a ‘tentative’ World Heritage Site to UNESCO in 2010 under the title “The Royal Sites of Ireland”. UNESCO is responsible for the designation of World Heritage Sites and individual States are accountable to it for the subsequent management of all Sites. The deserved designation of the Royal Sites as a World Heritage Site would be of significant importance for Ireland and particularly Westmeath, given the competition globally for such designation. It would bring with it considerable tourism interest and the associated economic spin-offs to the area. For instance, the Giant's Causeway is a must see for international tourists visiting Northern Ireland, as is the Great Wall of China when visiting China. That is the potential of these ancient "Royal Sites" should they attain Unesco World Heritage Status. One of the key considerations in deciding on whether the Royal Sites of Ireland become a World Heritage Site will be that the integrity of the sites themselves and their integrity within the landscape in which they are sited have both been maintained. In this respect, the submission document from the Department in 2010 stated with regard to the visual integrity of these sites “based on preliminary observation the sites appear largely intact and to have retained their original attributes. Overall the sites are well preserved and retain high visual landscape qualities.” Furthermore, with ‘evocative’ sites, with little in the way of built or natural structures, integrity with and within the landscape is critical. Should wind energy development (which includes Wind Turbines and Pylons and cabling and related infrastructure), be built within a 25km radius of The Hill Uisneach, it will visually dominate and oppressively impose on this sensitive landscape. The Royal Site of Uisneach is located along the EPA Quiet Area belt which includes the Ancient Path for travellers along Irelands’ main thoroughfare, the Shannon, en route to Uisneach where Ballymore’s Lough Swedy (Protected view to Uisneach) contains and ancient bronze man-made island which hosted an ancient hostelry for travellers to the Royal Site of Uisneach. Both this ancient path and the Quiet Area belt overlap and run continuously from the Longford border to Ballymore (Lough Swedy), Shinglis, Moyvore, Rathconrath, Mount Dalton to Uisneach and beyond. Other significant areas in Westmeath which host both EPA Quiet Areas and areas of significant importance include, inter alia, Lough Derravaragh (Children of Lir), Lough Ennell and its surrounding lands (sanctuary to the High King Malachi II ) and substantial areas of North Westmeath which includes the areas from Fore (Fore Abbey and the Seven Wonders of Fore). This Quiet Area extends to and beyond Loughcrew’s Megalithic Tombs (3200 BC.), where the Meath County Development Plan objective is to seek Unesco World Heritage Status for Loughcrew. The Quiet Areas from Fore to 8|Page Loughcrew extend down the County in an inverted cruciform to an area just north of Raharney (Bracklyn, Westmeath), in which area itself hosts one of Westmeath’s 13 National Monuments: an important Ringfort. (Note, the above list of important sites and Quiet Area is not intended to be exhaustive.) Please see map below for EPA Quiet Areas superimposed at County Level for Westmeath. • It is submitted that in addition to Noise Assessment, that Visibility Modelling be carried out to ensure development is not visible from Quiet Areas and sensitive sites of national, regional and local importance. The EPA Environmental RTDI Programme pursuant to Environmental Noise Directive, identifies the importance of Quiet Areas to human wellbeing: “Ireland has a considerable number of large, open places of astonishing beauty and relative wildness. Each area can have a distinct and powerful aura, fully dependent upon the landscape, natural sounds and natural quiet. As such, these areas afford unique opportunities for undisrupted respite, solitude, contemplative recreation, inspiration, and education. Further, these areas also provide scarce refuges and undisturbed natural habitats for animals. This project has identified a significant number of Quiet Areas in rural Ireland, still largely unaffected by anthropogenic noise. In these areas, tranquillity can be achieved to the fullest extent in relation to not only sound but also the other senses of the body. The results of this research demonstrate that the quality of the natural soundscape in many areas is excellent; however, monitoring also identified how societal changes and human activity are impacting on Quiet Areas and the extent to which natural tranquillity or quietness can be disturbed by the introduction of man-made noise from transportation, industry and other activities. (pg. 22) 9|Page Noise should be included in environmental quality criteria and quality of life indices. A subsidiary EQO (Environmental Quality Objective) will be to protect selected Quiet Areas from the adverse effects of anthropogenic noise.” (pg. 17) There are many vulnerable sectors to noise within our community such as the elderly, children, persons suffering from vertigo and those within the autism spectrum. These sectors cannot tolerate increased noise levels. Quiet Areas are chosen for respite, and for instance the “Learning Difficulty Analyst Centre” which is a center for inter alia, screening for Dyslexia, Visual Perception difficulties and Neuro Development Therapy” is located in EPA Quiet Area just south of Delvin. The impact Wind Turbine Noise and Shadow Flicker on sensitive receptors vis a vis an evidenced based solution is particularised in detail in Section 4 to 10 below. • It is imperative that Quiet Areas and areas with sensitive receptors are fully protected from the introduction of anthropogenic wind farm noise pollution in the WEDG Focused Review so as to “to prevent the degradation of the acoustic quality.” 5. Absolute noise limit chosen / noise measurement indicators used. The adoption of an upper limit for wind turbine noise is appropriate and consistent with the approach adopted internationally for wind energy developments. I also support the application of a single appropriate upper limit for both day and night time noise, to protect residential amenity. However, the choice of a noise limit of 40dB LA90 10 min is not acceptable. As Dick Bowdler notes in his submission to the current WEDG submission phase,8 this proposed limit is actually significantly higher than most other jurisdictions, contrary to the statement in the draft WEDG (p.7) that this proposed limit is “in the lower end of the range of limits applied internationally”. Furthermore, there is no basis for the assertion that the draft WEDG limit of 40dBA LA90 10 min : “takes into account World Health Organisation findings in relation to night time noise.” In fact, the use of the LA90 10 min indicator, which is adopted primarily in Commonwealth countries to measure wind turbine noise, cannot be compared to the LAeq based indicator used by the World Health Organization and most other EU member States (and recommended by the EPA) for wind turbine noise unless the correct minus 2dB correction is made. To achieve an LA90 night noise level equivalent to the WHO night noise limit of 40dB would require a 38dB LA90 10 min limit. There is no evidence suggested or provided in either the Marshall Day report or the Draft WEDG to support the use of the LA90 indicator for the measurement of wind turbine noise. LA90 is essentially a determinate of the minimum noise level in the receiving environment and is commonly used to measure background noise or minimum environmental noise levels. As Marshall Day highlight in 8 http://www.environ.ie/en/DevelopmentHousing/PlanningDevelopment/Planning/PublicConsultations/Submis sions-WindEnergy/Unspecified/FileDownLoad,35130,en.pdf 10 | P a g e their report, the measured LA90 noise level reflects the noise level that is exceeded for 90% of the measurement survey period. Neither is there any evidence that the 40dB LA90 10min limit meets WHO standards or provides reasonable protection for residential amenity. On the contrary, there is mounting evidence that the use of the LA90 10 min indicator may not be appropriate for the measurement wind turbine noise.910 The AECOM Report for Defra on Wind Farm Noise (2011) confirms that “there are few if any standards that set noise limits using this index. Additionally it is argued that because the LA90 10 min index focuses on the quietest periods in the measurement period it is relatively insensitive to rapid fluctuations in noise level where the noise varies rapidly over a short periods e.g. as with aerodynamic/amplitude modulation, and the impact of such characteristics can be underestimated using the LA90,t noise index” [emphasis added]. This view is supported by the University of Salford Report on Health Impacts of Wind Turbines study which states (p.19) that: “the LAeq, t index is more sensitive to the modulating (time varying) nature of WT noise”). There is also sufficient evidence to show that wind turbine noise is more noticeable, annoying and disturbing than other industrial noise sources, such as rail, airway and road traffic noise due to its 9 https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/69222/pb-13584windfarm-noise-statutory-nuisance.pdf 10 http://usir.salford.ac.uk/29183/1/HealthEffects_Final_IQ1-2013_20130410.pdf 11 | P a g e duration, modulation and low frequency noise content.11 As the most recent JRC and WHO report for European authorities12 notes (p.46) wind farms are among: “a growing list of noise sources which fall into the scope of the END and may have a substantial health impact, but for which exposure reporting to the European Commission is not required.” Health Impact studies in relation to the impact of wind turbine are currently being undertaken in Canada, Denmark, Germany, while a further study of low frequency noise from wind farms was recently announced in Australia. Research from the ongoing Japanese study into the health impact of wind turbines undertaken by Seong et al (2013)13 suggests that the most appropriate indicator to measure wind turbine noise in the context of health impact is the LAmax noise parameter. This is consistent with the approach suggested by the WHO (1999) for modulating noise sources. Specifically, as far back as 1999, the WHO Guidelines for Community Noise (1999) state (p.58) that: “If the noise is not continuous, LAmax or SEL are used to indicate the probability of noiseinduced awakenings. Effects have been observed at individual LAmax exposures of 45dB or less. Consequently, it is important to limit the number of noise events with a LAmax exceeding 45dB. Therefore, the guidelines should be based on a combination of values of 30dB LAeq, 8h and 45 dB LAmax. To protect sensitive persons, a still lower guideline value would be preferred when the background level is low. Sleep disturbance from intermittent noise events increases with the maximum noise level. Even if the total equivalent noise level is fairly low, a small number of noise events with a high maximum sound pressure level will affect sleep.” Given the growing body of evidence in relation to the adverse impact of wind turbine noise14 the lack of any evidence-based approach in the draft WEDG to the setting or assessment of wind turbine noise limits is of concern. 11 See, for example, World Health Organization, Night Noise Guidelines for Europe (2009); Pedersen “Health aspects associated with wind turbine noise - results from three field studies” 59(1) Journal of Noise Control Engineering (2011) pp. 47-53; Pedersen et al “Response to noise from modern wind farms in The Netherlands” 126(2) Journal of the Acoustical Society of America (2009) pp. 634-643; Shepherd et al “Evaluating the impact of wind turbine noise on health-related quality of life” 13(54) Noise and Health (2011) pp.333-339; Moeller and Pedersen “Low-frequency noise from large turbines” 129(6) Journal of the Acoustical Society of America (2011) pp. 3727-3744; Janssen et al “A comparison between exposure-response relationships for wind turbine”; Suter Noise and Its Effects, Administrative Conference of the United States, 1991; http://www.cfp.ca/content/59/5/473.full; BMJ 2012;344:e1527 doi: 10.1136/bmj.e1527 (published 8 March 2012). 12 http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0008/179117/Methodological-guidance-for-estimatingthe-burden-of-disease-from-environmental-noise-ver-2.pdf 13 http://docs.wind-watch.org/internoise-2013-0595.pdf 14 Bakker RH, Pedersen E, van den Berg GP, Stewart RD, Lok W, Bouma J. Impact of wind turbine sound on annoyance, self-reported sleep disturbance and psychological distress. Science of the Total Environment 2012 May 15;425:42-51; Janssen SA, Vos H, Eisses AR, Pedersen E. A comparison between exposure-response relationships for wind turbine annoyance and annoyance due to other sources. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 2011; 130(6):3746-53; Krogh C, Gillis L, Kouwen N, Aramini J. WindVOiCe, a self-reporting survey: adverse health effects, industrial wind turbines, and the need for vigilance monitoring. Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society 2011;31:334-9; Møller M, Pedersen C. Low frequency noise from large wind turbines. Journal of the Acoustic Society of America 2010; Nissenbaum M, Aramini J, Hanning C. Effects of 12 | P a g e • It is imperative that the LAeq noise indicator be used by WEDG as it is by Europe, WHO and as recommended by the EPA and AECOM Report for Defra in the UK. In accordance with the World Health Organisation, “the guidelines should be based on a combination of values of 30dB LAeq”. “To protect sensitive persons, a still lower guideline value would be preferred when the background level is low.” Furthermore and as submitted at section 2 above, the WEDG Review must take account of existing background noise levels (to include character, magnitude and complexity) and sensitivity of locations (sensitive receptors and Quiet areas) and in accordance with comparable projects such as the DART underground, set “a maximum increase of 3dBA, on the lowest reoccurring LA90 5mins”. Under no circumstances should the substantial adverse impact threshold of a 5dB (or greater) increase in background noise be permitted. 6. Shadow Flicker Control We agree that no existing dwelling or other accepted property should have to endure shadow flicker. We accept that at distances greater than 10 rotor diameters, the potential for shadow flicker is extremely low in flat terrain, but this is not the case where wind turbines are sited on elevated hills and ridges. Incidences of shadow flicker are occurring at dwellings further than 10 rotor diameters from large turbines. This issue needs to be addressed in the draft WEDG. While modern wind turbines have the facility to reduce or stop turbine rotation when shadow flicker is likely to occur, these mechanisms are currently not being employed at many locations. Unless industrial wind turbine noise on sleep and health. Noise & Health 2012 September-October;14:237-43; Nissenbaum M, Aramini J, Hanning C. Adverse health effects of industrial wind turbines: a preliminary report. Proceedings of 10th International Congress on Noise as a Public Health Problem (ICBEN), 2011, London, UK. Curran Associates, 2011; Pedersen E. Effects of wind turbine noise on humans. Proceedings of the Third International Meeting on Wind Turbine Noise, Aalborg, Denmark, 17-19 June 2009; Pedersen E. Health aspects associated with wind turbine noise — results from three field studies. Noise Control Engineering Journal 2011;59:47–53; Pedersen E, Larsman P. The impact of visual factors on noise annoyance among people living in the vicinity of wind turbines. Journal of Environmental Psychology2008;28(4):379–89; Pedersen E, Persson Waye K. Perception and annoyance due to wind turbine noise — a dose-response relationship. Journal of the Acoustic Society of America 2004;116:3460–70; Pedersen E, Persson Waye K. Perception and annoyance due to wind turbine noise — a dose-response relationship. Journal of the Acoustic Society of America 2004;116:3460– 70; Pedersen E, Persson Waye K. Wind turbine noise, annoyance and self-reported health and well-being in different living environments. Occupational and Environmental Medicine 2007 Jul;64(7):480-6; Pedersen E, Persson Waye K. Wind turbines – low level noise sources interfering with restoration? Environmental Research Letters 2008;3:015002; Pedersen E, van den Berg F, Bakker R, Bouma J. Can road traffic mask sound from wind turbines? Response to wind turbine sound at different levels of road traffic sound. Energy Policy 2010;38:25207; Phillips C. Properly interpreting the epidemiologic evidence about the health effects of industrial wind turbines on nearby residents. Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society 2011;31:303-8; Salt AN, Hullar TE. Responses of the ear to low frequency sounds, infrasound and wind turbines. Hearing Research 2010; 268:12– 21; Salt A, Kaltenbach J. Infrasound from wind turbines could affect humans. Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society 2011;31:296–303; Shepherd D, McBride D, Welch D, Dirks K, Hill E. Evaluating the impact of wind turbine noise on health related quality of life. Noise & Health 2011;13:333–9; van den Berg GP. Effects of the wind profile at night on wind turbine sound. Journal of Sound and Vibration 2003;277:955–70; van den Berg G, Pedersen E, Bouma J, Bakker R. Project WINDFARMperception. Visual and acoustic impact of wind turbine farms on residents. FP6–2005-Science-and-Society-20. Specific support action project no 044628, 2008. 13 | P a g e there is a mandatory provision in the draft WEDG to prevent shadow flicker from occurring at nearby homes, we believe that wind turbines will continue to cause considerable distress to those in close proximity to these developments. • It is imperative that a mandatory provision be provided in the WEDG to prevent shadow flicker from occurring at nearby homes. Use definitive language only e.g. use the words “must” instead of “should”. 7. Setback Distance from Homes We concur with the finding of the Marshall Day report that setback distance is not an appropriate approach to take solely as a means of noise control. As noted in the Draft WEDG, setback distance is also required: “in order to provide for other amenity considerations e.g. visual obtrusion.” Recent independent studies on the impact of wind turbines on property values confirm the on-theground experience of property auctioneers and valuers that wind turbines adversely impact property values.15 The most recent independent study undertaken over a 12 year period by the London School of Economics (which is due to be published in March 2014)16 looked at over one million sales of properties within close proximity of 150 wind farm sites in England and Wales. The results of this survey confirm that homes within 2km of wind turbines will experience the greatest devaluation, on average 11%, but the study also finds that homes 4km from a wind farm site also experience a diminution in property value of 3%. Sunak and Madlener (Rev. March 2013: The Impact of Wind Farms on Property Values: A Geographically Weighted Hedonic Pricing Model), demonstrated through a comprehensive study of Wind Farm effects on house sales in Germany that a house price reduction of between 21.9 and 28% can be expected within 2km. The Marshall Day report highlighted that a significant number of the 550 submissions received during public consultation on the Wind Energy Guidelines Focused Review supported mandatory setbacks that were: “generally significantly higher than the 500 m separation referenced in WEDG06” (p.99). Despite this, the draft WEDG have maintained a setback distance of 500m: “because of the lack of correlation between separation distance and wind turbine sound levels.” This approach is in conflict with the requirements of the EIA Directive, which as the EU Court of Justice confirmed in Case C-420/11, EU Jutta Leth v Republik Österreich 15 http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2114216 16 http://www.telegraph.co.uk/earth/energy/10597785/Wind-farms-proven-to-cut-house-prices-by-11-saysLSE-report.html 14 | P a g e “the prevention of pecuniary damage, in so far as that damage is the direct economic consequence of the environmental effects of a public or private project, is covered by the objective of protection pursued by Directive 85/337”. When considering setback, the Draft WEDG have failed to consider or assess the relationship between proximity to wind energy developments and diminution of residential amenity and property values. The draft WEDG also ignore the findings of the Marshall Day Report that setbacks: “may be required for other reasons, such as occupational health and safety buffer zones” (p.61). Separation distances are not only required to avoid adverse noise and shadow flicker impacts, but because of the enhanced safety risk arising from blade failure or turbine collapse. The throw distances of debris from a falling turbine can be confirmed by calculation, but debris is documented as travelling distances of over 1km. Evidence of the throw distance from the turbine collapse in Donegal in March 2013 should be considered in the context of appropriate setback distances, to ensure the public safety of those living in close proximity to wind energy developments. I also note the Irish Thoroughbred Breeders Association (and Thoroughbred Trainers & Jockeys Associations) position on a mandatory setback from registered Stud Farms and Equine centres to fully protect the health and safety of their industry (staff and horses). Finally, a number of recent critical studies advocated setback distances of 1.5km – 2km, on the basis of noise and associated sleep disruption: Dr Chris Hanning1, Consultant in Sleep Disorders, UK who discusses adverse impacts on sleep at distances of up to 2km and greater, based on a turbine height of 125m. Yano etc al, discuss levels of Severe Annoyance experienced by residents in close proximity to Wind Farms in Japan (North to South), showing that a set-back distance of minimum 1.5km is required from homes to minimise sever annoyance for rural residents. Dose-response relationships for wind turbine noise in Japan - Yano, Kuwano, Kageyama, Sueoka and Tachibana), presented at InterNoise (Noise Control for Quality of Life conference), Innsbruck, Austria, September 2013. • It is imperative that the WEDG Review, in accordance with the EIA Directive, and the EU Court of Justice ruling Case C-420/11, consider and assess the relationship between proximity to wind energy developments and diminution of residential amenity and property values and that occupational health and safety buffer zones be incorporated. Notwithstanding all of the above, a set-back distance of 10 times Turbine height (from base to blade tip) must be a mandatory limit set within the Guidelines in order to be future-proof and protect rural communities from noise pollution. i.e. to be able to cater for the planned significant increase in turbine heights and turbine capacity in coming years. This set-back distance rule is particularly relevant due to the lack of trust created by the Department of Energy and Dept of the Environment in relation to responsible planning considerations and Guidelines, specific to Industrial Wind Development. 15 | P a g e Yours Sincerely, Killucan-Raharney Wind Information Group Committee: Daryl Kennedy, Lucy Looby, Seamus Goonery, Catherine Doyle, Tom Mockler, Jimmy Duffy, Mary Tifft, Vincent Cunningham, Maddie Dineen, Ray Oliver, Richard O’Keeffe, Tony Collins -on behalf of the above community. 16 | P a g e