Courage

advertisement

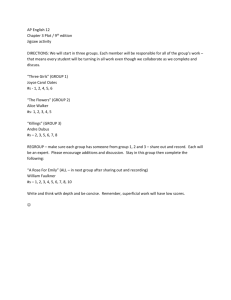

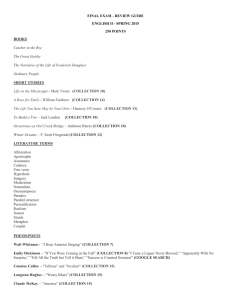

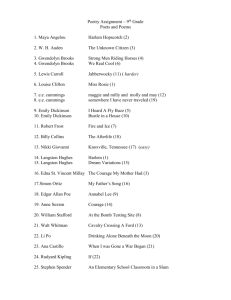

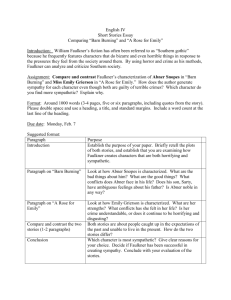

English III 2014 Spring Semester Review I. Short Story Analysis – you will read a contemporary short story and answer questions. Be sure to know the following terms for literary analysis: conflict tone metaphor simile allegory irony climax theme II. Poetry Analysis – “Courage” on p. 1212 of your textbook and attached to this review. Be sure to know the following terms for analysis: internal rhyme blank verse approximate rhyme free verse simile metaphor allusion personification mood III. Speech Analysis – you will analyze Faulkner’s Nobel Prize acceptance speech found on p. 904 of your textbook. A copy of the speech is attached to this review. purpose tone IV. Literary Movements & Authors Movements: Realism Regionalism Naturalism Harlem Renaissance Modernism Lost Generation Imagism Contemporary Authors: Mark Twain Stephen Crane Ambrose Bierce John Steinbeck Ernest Hemingway William Faulkner Robert Frost Willa Cather Flannery O’Connor Kate Chopin Amy Tan Langston Hughes ee cummings Toni Morrison V. Literature – Realism, Harlem Renaissance, Modernism, Contemporary “I Hear America Singing” by Walt Whitman – p. 424 – Poem will be on the exam. free verse slant rhyme parallelism repetition “I Too” by Langston Hughes – p. 832 – Poem will be on the exam. symbolism “A Rose for Emily” by William Faulkner – p. 896 – The story will NOT be on the exam. Describe the main character, Emily Grierson. How does the small-town setting affect the story? What does the house represent? What is its condition at the end of the story? Describe Emily’s relationship with her father. What were the expectations for women during this time period? How does Emily react to the town’s request for her to pay her taxes? How does Emily react to her father’s death? Why does Emily go to the druggist? How does Emily get what she wants? What happens to Homer Barron? What happens at the end of the story? What does the strand of gray hair display at the end of the story? Crossover War Selections – pp. 1191-1198 – The selections will NOT be on the exam. Why does the narrator in “Ambush” throw the grenade? How does the narrator in “Ambush” feel about his actions? What is discussed in “The Gift of Wartime”? In Stay Alive, My Son, what decision does Pin Yathay make about his son? Why? In Stay Alive, My Son, how does Any feel about Pin’s decision? What is the tone of “Camouflaging the Chimera” and how does the tone affect the poem’s message? VI. SAT Vocabulary – Units 10 – 12 – The words from units 10 – 12 of the fourth nine weeks will be used in sentences. VII. Research: Be able to apply the research skills you gained through your research project. Some terms/skills needed: Works Cited page – how is it organized? MLA parenthetical citations – How do you punctuate parenthetical citations? What information is included in parenthetical citations? Research sources – How do you know which sources are best for a particular topic? What is plagiarism? What is the role of an editor? An author? A translator? Why is documentation important? VIII. Grammar: Be apply to revise and edit selections, especially sentence combining. Be able to identify and create: simple sentence compound sentence complex sentence periodic sentence interrogatory sentence imperative sentence declarative sentence exclamatory sentence Courage by Anne Sexton It is in the small things we see it. The child’s first step, as awesome as an earthquake. The first time you rode a bike, wallowing up the sidewalk. The first spanking when your heart went on a journey all alone. When they called you crybaby or poor or fatty or crazy and made you into an alien, you drank their acid and concealed it. Later, if you faced the death of bombs and bullets you did not do it with a banner, you did it with only a hat to cover your heart. You did not fondle the weakness inside you though it was there. Your courage was a small coal that you kept swallowing. If a buddy saved you and died himself in so doing, then his courage was not courage, it was love: love as simple as shaving soap. Later, if you have endured a great despair, then you did it alone, getting a transfusion from the fire, picking the scabs off your heart, then wringing it out like a sock. Next, my kinsman, you powdered your sorrow, you gave it a back rub and then you covered it with a blanket and after it had slept a while it woke to the wings of the roses and was transformed. Later, when you face old age and its natural conclusion your courage will still be shown in the little ways, each spring will be a sword you’ll sharpen, those you love will live in a fever of love, and you’ll bargain with the calendar and at the last moment when death opens the back door you’ll put on your carpet slippers and stride out. 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 40 45 William Faulkner, probably the most important American novelist of the twentieth century, made this Nobel Prize acceptance speech in Stockholm, Sweden, on December 10, 1950. 1 I feel that this award was not made to me as a man, but to my work – a life’s work in the agony and sweat of the human spirit, not for glory and least of all for profit, but to create out of the materials of the human spirit something which did not exist before. So this award is only mine in trust. It will not be difficult to find a dedication for the money part of it commensurate with the purpose and significance of its origin. But I would like to do the same with the acclaim too, by using this moment as a pinnacle from which I might be listened to by the young men and women already dedicated to the same anguish and travail, among whom is already that one who will someday stand here where I am standing. 2 Our tragedy today is a general and universal physical fear so long sustained by now that we can even bear it. There are no longer problems of the spirit. There is only one question: When will I be blown up? Because of this, the young man or woman writing today has forgotten the problems of the human heart in conflict with itself which alone can make good writing because only that is worth writing about, worth the agony and the sweat. 3 He must learn them again. He must teach himself that the basest of all things is to be afraid; and, teaching himself that, forget it forever, leaving no room in his workshop for anything but the old verities and truths of the heart, the old universal truths lacking which any story is ephemeral and doomed – love and honor and pity and pride and compassion and sacrifice. Until he does so, he labors under a curse. He writes not of love but of lust, of defeats in which nobody loses anything of value, of victories without hope and worst of all, without pity or compassion. His griefs grieve on no universal bones, leaving no scars. He writes not of the heart but of the glands. 4 Until he relearns these things, he will write as though he stood among and watched the end of man. I decline to accept the end of man. It is easy enough to say that man is immortal simply because he will endure: that when the last ding-dong of doom has clanged and faded from the last worthless rock hanging tideless in the last red and dying evening, that even then there will still be one more sound: that of his puny inexhaustible voice, still talking. I refuse to accept this. I believe that man will not merely endure: he will prevail. He is immortal, not because he alone among creatures has an inexhaustible voice, but because he has a soul, a spirit capable of compassion and sacrifice and endurance. The poet’s, the writer’s, duty is to write about these things. It is his privilege to help man endure by lifting his heart, by reminding him of the courage and honor and hope and pride and compassion and pity and sacrifice which have been the glory of his past. The poet’s voice need not merely be the record of man, it can be one of the props, the pillars to help him endure and prevail.