Critical & Post-structuralist IR

advertisement

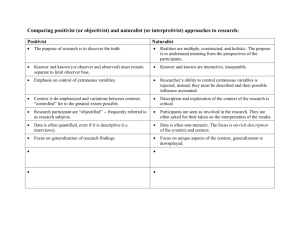

Jevgenia Viktorova University of St Andrews E-mail: jv2 [ät] st-and.ac.uk Critical theory Post-structuralist IR Philosophical underpinnings: ◦ ◦ positivism vs. anti-/post-positivism; foundationalism vs. anti-foundationalism Marxism and structuralism Feminist IR Defining characteristics of critical and poststructuralist theories: (1) do not consider IR as a free-standing discipline in its own right, but rather seek to place it into a broader context of social thought; (2) hold that the purpose of theory is to ‘unsettle’ established categories and ‘disconcert the reader’ (Brown 2005) Robert Cox (1981) ‘Social Forces, States and World Orders: Beyond International Relations Theory’: ◦ a distinction between ‘problem-solving’ and ‘critical’ theory ◦ theory is ‘always for someone and for some purpose’ ◦ it is always an expression of a perspective ◦ and situated in space and time (historically specific) Theory can serve two distinct purposes: (1) to offer a ‘direct response’ to help solve problems posed within the terms of a particular perspective (2) to reflect upon the process of theorising itself: on the perspective which gave rise to it and its relations with other perspectives on possibilities of ‘choosing a different valid perspective from which the problematic becomes one of creating an alternative world’ (Cox 1981) The first purpose gives rise to conventional, ‘problem-solving’ theory: ◦ accepts the prevailing definition of a particular situation as ‘given’ ◦ is geared towards solving the problem that this particular definition generates The majority of IR theories (such as liberalism and realism) The second purpose leads to critical theory: ◦ does not view the definitions of social reality as given; ◦ always seeks to elucidate: how a particular definition serves certain interests how it closes down particular sorts of arguments ◦ ‘directed toward an appraisal of the very framework for action, or problematic, which problem-solving theory accepts as its parameters’ (Cox 1981) ◦ concerned with the process of historical change: its object is continually changing critical theorising is never complete Critical theory lacks precision of problemsolving theory The precision of problem-solving theories is ‘costly’: ◦ by representing the social and political orders as fixed they are ideologically biased to ignore evidence (and possibility) of change ◦ serve particular interests (e.g. national, class etc.) invested in the status quo. ◦ conservative orientation ◦ not value-free Critical theory is emancipatory: ◦ ‘approaches practice from a perspective that transcends that of existing order’ and ‘allows for a normative choice in favour’ of a different political order (Cox 1981) Antonio Gramsci; Frankfurt School Horkheimer’s inaugural lecture on ‘Traditional vs. Critical theory’ Critical theory: ◦ should investigate how the world in which the theorist finds him- or herself has got to be this way ◦ asks historical questions ◦ emancipatory: exposes the existing world order as non-arbitrary enquires into interests and forces that shaped its movement along a particular historical trajectory uncovers other possible routes ◦ ‘constructivist’ since it views the given reality as a construct – a result of human action in all its guises Richard Ashley: ‘The Poverty of Neorealism’ in Robert Keohane, Neorealism and Its Critics (1986) Based on: A Foucauldian account of social process: R.B.J. Walker; James Der Derian; David Campbell ◦ Habermas’s critical account of social sciences ◦ French post-structuralism (Foucault, Derrida ◦ a focus on power-knowledge nexus (interplay between ‘systems of power’ and ‘systems of knowledge’) ◦ different historical periods are characterised by different structures of power-knowledge relations Habermas – a successor of Frankfurt School ◦ Adorno’s PhD student ◦ inherited Horkheimer’s chair Habermas’s works include: ◦ Knowledge and Human Interest ◦ Legitimation Crisis ◦ Theory of Communicative Action (a rethinking of social sciences in 2 vols., 1981-2): A mission to re-energise an independent public sphere to counterbalance spoon-fed ‘truths’ about reality from those in power Critical theory’s boarder intellectual origins in Marxism Marx formulated the global-level ‘emancipation project’: ◦ political emancipation ◦ elimination of economic inequality Historical emphasis: ◦ ‘historical materialism’ ◦ mostly, historic change has been un-emancipatory Recognition that a given order serves particular interests ◦ e.g. class; or the ‘developed countries of the West’ Representation of the existing order as ‘natural’: ◦ Gramsci: ‘hegemony’ John Ruggie in IPE A reaction to Waltz: ◦ Neorealist view of international system does not account for historic change ◦ Realism as a mode of reasoning is not genuinely historical even where its ‘material’ is derived from history ◦ Dictates that with regard to the ‘essentials’, the future will always be like the past: ◦ Realist IR theory is a status quo theory: not ‘emancipatory’ Liberalism was originally seen as emancipatory: ◦ In the context of the Enlightenment, its function was to free humanity ‘from self-imposed immaturity’ (Kant) Liberalism ceased to be emancipatory Critical theorists: there is need for a different kind of theorising to ‘rescue’ the emancipation project Post-structuralists (drawing on Nietzsche, Foucault, Derrida): emancipation project is doomed Possibility of emancipation premised on ontological and epistemological assumptions: ◦ Positivism vs. anti- or post-positivism; ◦ Foundationalism vs. anti-foundationalism the ‘scientific’ = positivist method for social sciences: 1. make a conjecture about causality; 2. formulate that conjecture as a hypothesis consistent with established theory; 3. specify the observable implications of the hypothesis; 4. test for whether those implications obtain in the real world; 5. and report one’s findings, ensuring that one’s procedures are publicly known and hence replicable to other members of a particular scientific community that he identified as the IR community of scholars (e.g. Keohane) Following this method, one will a positivist methodological framework assumes that: ◦ attain ‘objective’ truth about the social reality? ◦ contribute to a wider agreement on descriptive facts and causal relationships, based on transparent and replicable methods ◦ the social world is amenable to the kinds of regularities that can be explained by using causal analysis with tools borrowed from the natural sciences ◦ the way to determine the truth of statements is by appealing to neutral facts established by Hume; summarised, e.g., by Kolakowski (Positivist Philosophy (1972)): (1) the rule of phenomenalism: only phenomena that can be directly experienced can generate knowledge of the real nature of the world (2) the rule of nominalism: proposes that general statements about the world that do not have their reference in independent, observable, atomized objects should not be afforded real knowledge status 3) value judgements are not part of science: values cannot be observed or verified and thus are ‘metaphysical’ categories, not facts; (4) unity of scientific method: the methods of natural sciences are applicable to social and political analysis Observance of positivist rules restricts possible objects for scientific enquiry Enticement of ‘scientific’ status? One can question ◦ possibility of adhering to the rules of positivism ◦ the validity of the rules themselves Critique of positivism How to account for differences in direct sensory experiences? Natural sciences: ◦ objective verifiable measurements, repeated experimentation etc. Social sciences: problematic ◦ Observable reality does not neatly fall into predefined clear categories ◦ e.g. assigning a case to a category involves a value judgement Hume’s philosophical position is predicated on the distinction between: ◦ an objectively existing sphere of reality ‘out there’ ◦ a thinking subject who (passively) receives: sense ‘impressions’ and constructs ‘theoretical’ images of the facts (‘ideas’) Sense ‘impressions’ are fundamentally different from the retrospective/theoretical realm of ‘ideas’: ◦ ‘idea’ realm does not correspond with reality per se ◦ because an abstract category does not correspond with what actually (physically) exists in the universe Hume’s conclusion: ◦ because we never directly experience external bodies ◦ we cannot experience a correlation between those bodies and the impressions they cause Therefore, empiricist based claims for real knowledge cannot be defended except in metaphysical terms (i.e. something beyond the immediate physical reality): ◦ ‘The implication of this position is clear enough: there is no logical basis, even in positivism’s own terms, for the proposition that knowledge of reality is directly derived from an independent world “out there”.’ (George, 1994) Has to make use of language: This potentially introduces: Does not ask the question of ends of theorising: ◦ Natural language is imprecise, open to multiple understandings ◦ Positivism counters this with establishing special languages of science and abstract terminologies, but: ◦ Terms still need to be defined through natural language ◦ uncontrollable variance in understandings of what one or another term implies and value-laden connotations ◦ does not problematise its impact on the world ◦ irresponsible: ‘Treating the feelings as mere effects of causal processes takes them out of our hands, and relieves us of responsibility’ (Toulmin 1990) The foundation of positivist science rests on infallibility of logico-mathematical procedures of thought: ◦ Universal and unbiased by sensory input ◦ Descartes: ‘cogito ergo sum’ ◦ Belief that whoever follows these procedures of reasoning is bound to arrive at the same conclusions about what is knowable in the world: ◦ Oakeshott (1962): a rationalist finds ‘it difficult to believe that anyone who can think honestly and clearly will think differently from himself’ The rational dichotomy of reason vs. sensual experience a separation into subjects that can be studied scientifically and those that cannot: ◦ Despite the alleged universality and timelessness of the rational method, it deliberately confines itself to a narrow selection of subjects and kinds of knowledge that can be achieved with regard to them ‘Certainty’ of science is achieved at the expense of a vast expanse of the unknown beyond its limits Embrace Wittgenstein’s realisation that This position is called anti-foundationalism: ◦ ‘no independent or objective sources of support’ can exist ‘outside of our language and actions’ ◦ ‘the facts of the world (e.g., historical, political, social) are always intrinsically bound up with the way we give meaning to them and accord them “real” status. This is an interpretive process grounded in historico-philosophical, cultural, and linguistic complexity, not in some Archimedean point of ultimate reference beyond history and society’ (George 1994) Deny the possibility of an independent, value-free perspective that could produce universally valid knowledge Positivist social theory insists that ◦ unless there is certain knowledge there can be no real knowledge at all ◦ ‘either there is some support for our being, a fixed foundation for our knowledge, or we cannot escape the forces of darkness that envelop us with madness, with intellectual and moral chaos’ (Bernstein) ◦ any approach that refuses to privilege a single perspective (as corresponding to reality) is guilty of relativism and is unable to make judgements about everyday life and political conflict Post-positivists argue that although there may be no ‘absolute’ knowledge, this does not undermine one’s ability to make decisions in the world: ◦ this ‘allows for a decision-making regime based on personal and social responsibility’ which is not relegated ‘to objectified sources “out there” (e.g., the system, the government, science, the party, the state, history, human nature)’ (George, 1994) Post-positivist methods: ◦ Discourse analysis - a ‘language turn’ (e.g. Foucault; Milliken) ◦ Analysis of practices (Neumann 2002) ◦ Shift from ‘mimetic’ approaches (that attempt to model reality) to aesthetic ones (aimed to relive reality in unique creative ways (Bleiker 2001) Natural sciences also have moved on: ◦ New approaches: chaos theory, complexity theory, quantum theory, discoveries in life sciences ◦ This changed the outlook of natural sciences and affected their methodology Social science positivists out of touch with these developments? Constructivist scholars differ in the extent to which they view their approach as antithetic to positivism Predominantly, do not emphasise their antipositivistic stance Most IR constructivists share following features: ◦ Interpretive understanding as an intrinsic (albeit not necessarily exclusive) part of any causal explanation ◦ Preference for middle-range theorising as opposed to ‘grand theory’ ◦ Recognition that social scientists are part of the social world which they are trying to analyse (‘double hermeneutics’) Thomas Risse: ‘is anybody still a positivist?’ Although positivist scholars reject normative issues, they agree with critical theorists on this: ◦ theory has a direct impact on the world: ◦ ‘good theory’ should inform (and change) practice Post-structural theorists are doubtful of this impact ◦ do not purport to create emancipatory theories ◦ that would simply substitute one view of reality informed by particular interests with another view – or one discourse with another ◦ concerned with exposing the terms on which one or another description of reality hangs together IR structuralism: ◦ IPE (International Political Economy): e.g. Wallenstein's world-systems approach (cores, peripheries and semiperipheries); dependency relations between North and South (e.g. Dependencia theory) ◦ peace studies (the view of structural inequalities as a major source of conflict and unrest (e.g. Johan Galtung) structuralism in semiotics and linguistics: ◦ influenced the development of French post-structuralist philosophy (Derrida, Foucault, Deleuze and Guattari etc.) ◦ and through it the more ‘radical’ IR post-structuralists impact on social theory at large viewed the structure of language (‘alphabet’ and ‘grammar’ broadly defined) as the generator of meaning The 1968 political unrest (student demonstrations etc.) in France signified a major turn in this thinking: ◦ exposed its etatisme and excessive stress on continuity ◦ failure to account for the dynamics of change ◦ questioned the Saussurean emphasis on ‘langue’ (language) as opposed to ‘parole’ (‘speech’) - i.e. the uses of language produced from the deeprooted structures of language ◦ speech – or rather writing – came into a spotlight (e.g. Derrida) Discourse analysis and genealogical enquiries Deconstruction: seeks to unsettle stable concepts and demonstrate the effects and costs of the settled concepts and oppositions, to disclose the ‘parasitical relationships between opposed terms and to attempt a displacement of them Double reading: ◦ The first reading is a commentary on the dominant interpretation demonstrating how it achieves its stability. ◦ The second reading applies pressure to the points of instability within a text, with the purpose of exposing how any story depends on suppression of internal tensions in order to achieve homogeneity and continuity. David Campbell (1992) Writing Security: ◦ a critique of the US foreign policy ◦ its reliance on radical ‘othering’ ◦ Search for a new ‘enemy’ image after the Cold War William Connolly’s work on ‘Culture Wars’ of the present-day US ◦ its categorising and alienating effects. Neither has abandoned ‘critical’ emancipation James Der Derian: ◦ Foucault-inspired analyses of diplomatic practice ◦ Paul Virilio-inspired post-modern enquiries about how the virtual reality, increased speed of life and interactions are affecting our understanding of the international IR represents a gendered view of reality, that is premised on ‘masculine’ interests Not necessarily ‘post-structural’ or ‘critical’ in their methods; nor is feminism confined to IR Issues: In Gramsci’s terms: ◦ Women’s equality and greater visibility in politics ◦ Critique of the Enlightenment as premised on a voice that is ‘European, rationalist and male’ (and ‘white’). ◦ the ‘hegemony’ of the existing world order and the bulk of IR theorising has naturalised masculine interests ◦ women’s voices are consistently marginalised and silenced to challenge the often unseen androcentric/ masculine biases in the way that knowledge is constructed to develop accounts of the social world that trace the influence of gender in all our discursive categories, and especially ‘the international’ to question/ ‘dislocate’ what we accept as normal: E.g. Cynthia Weber (1999) Faking It: US Hegemony in a ‘Post-Phallic’ Era reject commitment to ‘scientific’ methodology claim no single standard of methodological correctness feminist knowledge has emerged from a deep scepticism about the claims of ‘universal’ knowledge, which, in reality, are based primarily on masculine experiences and perspectives regard knowledge-building is an ongoing process describe knowledge-building as emerging through ‘conversation’ with texts, research subjects, or data research focus is not only on the subordination of women, but also other disempowered people agree with positivists that research should pose questions that are ‘important’ in the ‘real world’ (King et al. 1994; Van Evera, 1997) disagree with the positivist definitions of ‘important’ and the ‘real world’ ◦ Conventionally, scientific progress is judged not on the merit of the questions that are asked but on how questions are answered ◦ Feminists find that the questions that are asked – and also questions that are not asked – are more important for judging knowledge. ◦ The questions that feminists ask are typically not answerable within a conventional social ‘science’ challenge the core assumptions of the discipline and deconstruct its central concepts E.g. ‘Why have wars predominantly been fought by men and how do gendered structures of masculinity and femininity legitimate war and militarism for both women and men? To answer such a question: ◦ challenge the separation of ‘public’ and ‘private’ ◦ seek to uncover continuities between disempowerment of women in the domestic sphere and in the public – political and international – life ◦ E.g. investigate military prostitution and rape as tools of war and instruments of state policy Knowledge based on the standpoint of women’s lives leads to more robust objectivity: ◦ broadens the base from which we derive knowledge ◦ the perspectives of marginalised people may reveal aspects of reality obscured by more orthodox approaches to knowledge-building Emphasis on sociological analyses that begin with individuals and the hierarchical social relations in which their lives are situated Reject the conventional separation between subject and object of research: ◦ acknowledging the subjective element in one’s analysis increases the objectivity of research Cynthia Enloe (2000) Bananas, Beaches and Jean Bethke Elshtain (1987) Women and War Base: Making Feminist Sense of International Politics Jill Steans (1998) Gender and International Relations: An Introduction (a textbook)