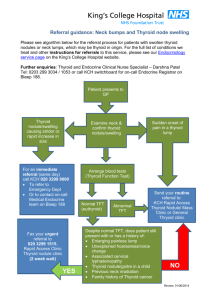

Medical Journal - Engish 2100 Project 1

advertisement

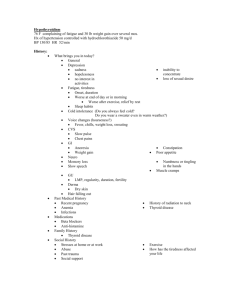

Medical Journal Sample Article Outline I. Presentation II. Assessment III. Diagnosis IV. Management V. Acknowledgments VI. References Presentation A palpable firm mass in the neck could suggest malignancy, but fortunately, that was not the ultimate diagnosis for a 50-year-old woman with a 2-month history of anterior neck pain. When she presented to the emergency department, she reported constant pain that did not worsen with swallowing, mastication, or neck movement. She had no dyspnea or hoarseness. Assessment On physical examination, the patient's neck was supple, and she had a normal range of motion. With palpation, a hard, mobile, nontender mass could be felt on the left side of the neck. No tracheal midline deviation was evident. Similarly, she had no skin abnormalities, such as dimpling or retraction of the overlying skin. Otherwise, her examination was normal. Lateral and anteroposterior neck radiography showed a large calcified mass in the left anterior neck. Neck sonography demonstrated a 5 cm by 7 cm anechoic mass with a posterior shadow in the left lobe of the thyroid gland. This finding corresponded with the calcified mass seen on plain x-ray. The patient had a palpable mass. (A) A lateral radiograph of the patient's neck showed a large calcified mass in the left anterior neck. (B) The mass was evident in another radiograph; this is an anteroposterior view. Laboratory studies, including a thyroid function test and an antithyroid antibody level, produced normal results. Fine-needle aspiration cytology of the thyroid revealed colloid and follicular cells with coarse calcified material. Diagnosis The patient received a diagnosis of nodular goiter with dystrophic calcification. Calcification within the thyroid gland can occur in both benign and malignant thyroid diseases. It is not uncommon, having been reported in up to 21% of plain x-rays.1 The most frequent occurrence among benign disorders is in the setting of multinodular hyperplasia.2 Three distinct patterns of intrathyroidal calcification have been described. Eggshell calcification, which might be misinterpreted as a calcified lymph node, usually indicates benign disease. In contrast, psammomatous calcification, found after fine-needle aspiration, is one of the most important diagnostic criteria of papillary thyroid cancer.3 This form is marked by the presence of psammoma bodies, microscopic rounded bodies with concentric rings and radial striations. Dystrophic calcification, the most common type, has a coarse, dense, and nodular appearance.1 It forms a nonspecific pattern and is caused by calcium deposition in abnormal thyroid tissue, as in necrosis and inflammation. In this regard, dystrophic calcification can be seen in both malignant and benign conditions.1 Management Because of ongoing neck pain, the patient underwent thyroidectomy. She is being treated with thyroid hormone replacement and has experienced no complications. Acknowledgments The authors would like to thank Professor Hossein Gharib, MD, from the Department of Endocrinology, Mayo Clinic College of Medicine, Rochester, MN, for his scientific comments and revision. References 1. Komolafe F. Radiological patterns and significance of thyroid calcification. Clin Radiol. 1981;32:571–575 2. Khoo ML, Asa SL, Witterick IJ, Freeman JL. Thyroid calcification and its association with thyroid carcinoma. Head Neck.2002;24:651–655 3. Das DK, Mallik MK, Haji BE, et al. Psammoma body and its precursors in papillary thyroid carcinoma: a study by fine-needle aspiration cytology. Diagn Cytopathol. 2004;31:380–386