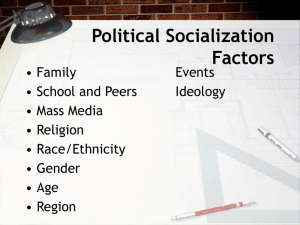

Lecture notes for agents of socialization

advertisement

(primarily drawn from “American Government” by James Q. Wilson and John J. DiIulio) Family is probably the primary influence on political affiliation 1- among high school seniors only 9 percent belong to members of the opposite party of their parents 2- In adults 60 percent are the same party and the rest are mostly independents, few are opposite party Do see more difference in policy areas Especially in areas of civil liberties and race in today’s young (note: if family is highly political then the communication of those norms is more effective and longstanding) Elementary school – give sense of national pride, idealized notion of gov., introduction of authority figures outside the family, gov. seen often as the president High school – Greater knowledge of system, can see erosion in trust of gov (especially among urban youth), most knowledgeable about current events than past history College – (important because about 25 % receive college degrees) Students usually become more liberal -- longer they are in college the more liberal they become 1. 2. 3. WHY? People who go to college may be prone to liberalism People are exposed to a wider variety of materials (possibly produced by a liberal cultural elite) College teaches liberalism (because of a belief in consistent idealism that leads to contempt for pragmatic compromises, institutions, and public opinion) Exception – The higher education level = more socially liberal (personal freedom), but more fiscally conservative (economic freedom) – possibly a reflection of class College kids today are entering college slightly more conservative than their predecessors in the 1970s How long do you stay liberal? Depends on: did you marry liberal? are your friends liberal? level of education, level of activism during college We usually have seen blue collar, or unskilled workers embrace Democratic and liberal views on economic policy Professionals tend to be more conservative on econ. policy But the electoral division between the classes seems to be narrowing many people vote on social, moral and foreign policy and not econ. Issues 2. education is liberalizing 1. African-Americans Hispanic Mostly Democratic (54%) but can have crossover (George W. Bush as governor) – Mexican American = Democratic, CubanAmerican = Republican Asian Heavily democratic (78%) (though younger Blacks more willing to vote Republican) Slim majority who are Republican (38 % Repub, 35% Dem) – Japanese = more conservative, Korean = more liberal White More likely to be Republican (35% Repub, 37% Dem) than Black or Hispanic (but not Asian) Since the 1960s – more men have been becoming Republicans creating a gender gap (is a pattern seen throughout the world) Main reason seems to be men’s conservatism on social issues like gay rights, abortion, gun control and size of government About 58% of women identify as Democrats Generally Protestants more conservative than Catholics who are more conservative than Jews Why? Class – Jews and Catholics were immigrants who saw more support with Liberals Religious tradition – Protestants – individual salvation Jews – social justice The difference is fading with time – tend not to see a lot of diff on economic issues, more difference on social issues South – more conservative socially Northeast – more liberal socially Midwest – more conservative socially West – More liberal socially Take out discussion questions on KEY… If you do not have some, prepare them…. A basic inquiry into American politics would show that some elections appear to matter more than others. To be sure, the amount of people, intensity of attitudes, nature of expected consequences, and impacts all vary. However, periodically a "critical" election comes along and creates durable new groupings of voters, revealing a sharp alteration in a pre-existing cleavage in the electorate. Critical election: An election that creates durable new groupings of voters, revealing a sharp alteration in a 'pre-existing' cleavage in the electorate. Key wishes to explain what he means by examining two elections: 1896 and 1928. He argues that 1928 was a realigning election due to the candidacy of Al Smith. Smith, who was of immigrant stock and Catholic, garnered support from fellow Catholics and recent immigrant groups. This set up the Roosevelt revolution (which is a bit ironic since Smith and Roosevelt did not like each other much). Key looks at two towns, Somerville (a Boston suburb with a significant Catholic and urban population) and Ashfield (which is quite the opposite). The towns show a sharp contrast, where Somerville began to support the Democrats quite sharply while Ashfield's support for Democrats was largely attenuated. Key supports this finding further by examining towns across Massachusetts, Connecticut, New Hampshire, Maine, Rhode Island, and Vermont (not presented). Towns that had the largest gains for Democrats remained Democratic. Those that lost support became Republican. These effects, Key notes, differ across states and are sometimes ephemeral. Moreover, enduring partisan shifts might have resulted only from the depression (i.e. they may have happened regardless of 1928). Key also analyzes the 1892-1896 period. His findings are a bit different than common knowledge. First, he finds that changes were in full swing by 1894. Second, changes in the electorate appear to not be along class lines (as common wisdom suggests that this was a "have vs. have-nots" battle) but rather regional (East vs. West). Whatever the cause and time frame, Key argues that both are critical elections since they, in some fashion, made realignments in the electorate that were sharp, visible, and relatively long lasting. Key's findings, as he admits, are very tentative. For instance, if the changes were in full swing in 1894, I would think that there is something we are missing. What happened in 1894? New Hampshire is fuzzy--when we are given Figure C (on page 8) we are presented with 22 Least Gain towns and 25 Most Gain towns. In Figure D (on page 10) we see New Hampshire now has 29 and 24 towns, respectively