The Onliness of Strong Brands Bloomberg Business Week / Jessie

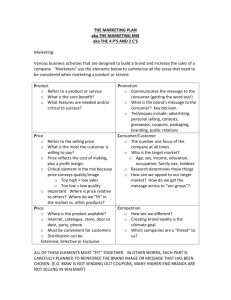

advertisement

The Onliness of Strong Brands Bloomberg Business Week / Jessie Scanlon / November 16, 2006 Marty Neumeier, author of Zag, talks about good vs. different, and zagging when others zig to make your brand stand out "Our brand is the only _____ that ______." Every company, in building a successful brand, should develop such an "onliness" statement, explains Marty Neumeier in his new book, Zag. If a company can't say briefly what makes its brand different from the competition, he advises, go back to the drawing board. So, who is Marty Neumeier? He's the founder and president of Neutron, a San Francisco-based brand consultancy. Better yet, he is the only design and brand expert who writes big-idea books filled with practical how-to advice designed to be read on a brief plane ride. (Actually, he would probably say that this onliness statement is too long.) In his book The Brand Gap, published in 2003, Neumeier addresses the wide gulf between business strategy and customer experience. Customers don't care about strategy, he argues, they care only about what your product, service, or company means in the context of their lives. And ultimately, "your brand isn't what you say it is—it's what they say it is" based on that experience. In fewer than 200 pages, Neumeier makes his case and proposes a complete system of brand-building based on the interaction of five disciplines: differentiation, collaboration, innovation, validation, and cultivation. Zag—a reference to the contrarian strategy of brand differentiation that is often attributed to John Hegarty, co-founder of ad firm BBH—takes a similar approach. It is part manifesto, part practical handbook, and you can read it between LaGuardia and Logan. In a series of e-mail exchanges, BusinessWeek.com editor Jessie Scanlon discussed trends, the challenge of the cluttered marketplace, and the key to zagging with Neumeier. An edited transcript of their conversation follows: With Zag, you delve into one piece of the unified theory of brand you laid out in The Brand Gap— differentiation, or as you call it "radical differentiation." What do you mean by that? Plain-old differentiation is beginning to fail in the face of increasing market clutter. Customers have so many choices today that they're beginning to shut down. Unless a brand, which I define as a customer's gut feeling about a product, service, or company, truly stands out from the clutter, it's doomed to incremental, evaporating profits as customers gravitate to the next, more meaningful brand. To build a real profit-making engine you need to start with radical differentiation. In other words, when everybody zigs, zag. That's easier said than done. One of the most thought-provoking elements in the book is a Good Versus Different graph, in which you plot products into four quadrants based on their performance along the two axes of good (high quality, workmanship, aesthetics, etc.) and different (surprising, fresh, offbeat, etc.). The surprise is that products in the Not Good and Not Different quadrant, obviously a bad place to be, tend to test well in market research, while products in the best quadrant of Good and Different tend to test poorly. That leaves companies in a bit of a quandary. It really does. How can a company bet on a winner, when the winner looks like a loser? Yet most of the great value-creating business ideas were initially rejected because the internal and external feedback was mixed or negative. Think of Post-It Notes—it took 3M (MMM) 11 years to imagine the product's potential. Or Herman Miller's Aeron chair, which customers said was the weirdest thing they'd ever sat in and would probably never buy. Or Cirque du Soleil, which people said would be boring without animals. If you apply straight-line metrics to ideas like these, you get a resounding "no-go". The trick is to evaluate ideas the way a designer would, by matching the customer reactions to previous success patterns. What you're looking for is not an idea that everybody believes is terrific, but an idea that gives people pause, yet that has undeniable benefits over existing alternatives. It takes intuition and experience to predict success this way, but I've found that the Good/Different tool gives companies more courage to greenlight the so-called "risky" ideas that create lasting profits. In the section on "finding your zag," you pass on some advice your mother gave you as a child:, "Find a parade and get in front of it." You use the story to illustrate the importance of finding and capitalizing on trends. What are your most valuable information sources or methods for trend-tracking? Other than Mom? Well, first I try to avoid getting hung up on specific predictions. You won't find the future in a book. Instead, I try to get my clients to look across the landscape of change with unfocused eyes, as it were. Powerful trends are easy to spot when you stand back far enough. For example, there's a big trend toward openness, shall we say, or transparency. There's a big trend toward democracy. There are trends toward green living, slow food, alternative energy. Toward a preference for experiences rather than products. Toward a sense of community. Toward DIY. Modernist design. Okay, but there are scores of trends, both mega and niche. Going back to your mother's advice, how does a company know which parade to get in front of? What is the right trend? The right trend is the one that aligns best with your brand. If I manage the Wheat Montana brand, for example, where I'm selling grind-it-yourself wheat in supermarkets, I'm probably not going to jump on the modern design trend. No, I'm going to ride the trends toward slow food, DIY gourmet cooking, healthy eating, and the kitchen as the center of home life. What can be really powerful is building your zag on several trends piled on top of each other. The iPod, for example, rides a bunch of trends—design, simplicity, miniaturization, widening broadband, return to community, and many others. These are all trends that are gaining, not waning. What do you recommend to a client who finds his brand riding a trend it never intended to ride? For instance, a few years ago Burberry, to its dismay, found itself riding the trend of hip hop/street chic. Live by the brand, die by the brand—or in Burberry's case, be embarrassed by the brand. It's a cruel world when customers own your brand. While you can't control the brand that customers build for you, you can influence it by giving them the right building materials. Burberry was blindsided because they didn't understand how their brand could be co-opted by another tribe. You write that "when you look under the hood of a high-performance brand, you almost always find it's powered by a trend." Trends are powerful, but they are also, well, trendy. They come and go. They're hot, they're stale. How should a brand relate to a trend that it surely wants to outlive? Let's not confuse a trend with a fad. Fads come and go quickly, and while they're here, they're in your face. Trends build slowly, and are so meek as to be almost invisible. The trend toward communicating by e-mail, for example, grew so slowly in the beginning that very few companies thought of building a business on it. Yet more and more people are shifting their business communications from voice to email. How many new opportunities are hidden in this fundamental change of behavior? You present the equation for a basic zag as "focus paired with differentiation supported by a trend and surrounded by compelling communications." Can you give a concrete example of this? All the high-performance brands do it. But let's take a truly great expression of this formula: Mini Cooper. The brand is completely focused on a single product, albeit with many possible flavors. It's differentiated, in that competing manufacturers were converging on the sport-utility vehicle market. It's riding multiple trends, including design (BMW styling), community ("Let's motor"), and green living (better gas mileage). And its communications are not only compelling, but in harmony with the brand's witty personality ("The last 3,000 pounds are the hardest to shed."). Zags shouldn't just happen at the product or service or company level, but at every level, including all the communications and company behaviors that surround the product or service or company. In helping a company find its zag, you suggest that it imagine that it has been wiped out in 25 years and it must write its own obituary. How is that useful? I was introduced to this exercise by my friends at C2, a firm that specializes in corporate storytelling. The idea is that you write your company's obituary the way you'd like it to read. What did you achieve? Why is the world a better place because you were in it? What this gets at is where the company's true passion lies. Passion is the beginning of an authentic brand—a brand that people will seek out because it gives more meaning to their lives. In looking at companies that have managed to zag—you mentioned 3M in the case of Post-Its or Herman Miller in the case of Aeron—do you see any common organizational structures or processes? Is there something in particular that allows these companies to navigate the Good/Different waters? My guess is that they succeeded mostly through the dogged persistence of one or two champions. But it doesn't have to be that way. When you understand that a breakthrough innovation exhibits a certain pattern in the early stages, seeing that pattern can instill the "group confidence" to go forward. You break down zagging into 17 steps. Of those, which is the most common point of failure? It depends on the company, but there's one point at which a lot of companies seem to fail—and when they fail here they have no real platform for building a brand. In the book it's checkpoint six, "What makes you the only?" The test for "onliness" can be found in this simple sentence: Our brand is the only _______ that ________. For example, Cirque du Soleil is the only circus that combines acrobatics with theatre. Unless you can fill in the blanks so that customers see your brand as both unique and compelling, you're starting in a hole. You'll have to scramble harder and spend more to get where you'd already be with a zag. In fact, you may never get there at all. Can you give an example of a company or product that failed at that point? All the world's me-too brands are busy failing, or at least not succeeding. Think about Burger King (BKC), Ford (F), Coldwater Creek (CWTR) clothing stores, Dasani water, Holiday Inn, Continental Airlines. You warn that "best practices" are usually "common practices" and as such are incompatible with zagging. Does zagging really mean abandoning all accepted best practices? You can't be a leader by following a leader. Period. Best practices are great for streamlining operations, but they won't catapult you ahead of the competition. In reality, best practices are just me-too practices, except for the companies that invented them. To compete in a fast-moving market you need "new practices"—inventive solutions that align with your onliness, that underscore your differentiation, and drive you forward. It would be an exhausting, not to mention wasteful, exercise to invent new practices in every part of your business, but a few new practices at the right leverage points can make all the difference. Do the fundamental principles of brand management need to change given the ever-increasing speed of the marketplace? The old fundamentals of brand management, demonstrated brilliantly by P&G in the last century, are no longer relevant. It was a top-down approach, and what we need today is a bottom-up approach. In the top-down days you could build a brand that lasted 25, 50, even 100 years. Today's brands are more likely to last only 5, 10, or 20 years. As P&G and others are realizing, we need new fundamentals that address the speed of the market, that create agile companies that can capitalize brands and quickly move on. If you're not zagging, you're lagging.