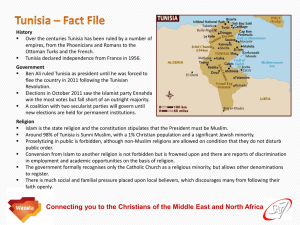

EU Policies and Democracy in Tunisia

advertisement