Judith Butler

advertisement

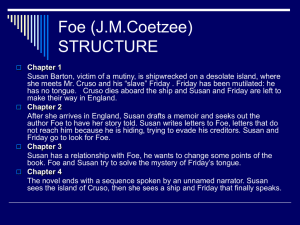

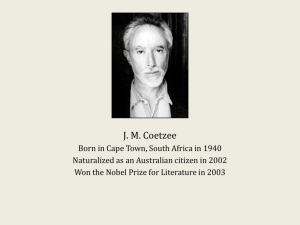

John Coetzee Foe Daniel Defoe - 1650-1731 John Coetzee The Text Coetzee's Foe has as intertext Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe written in 1719. (p. 134) Coetzee writes a minimalist text, highly palimsestic, which confronts the past (colonization and slavery) and the present of South Africa (the result of colonization and slavery). At the same time Foe parodies the XVIII century travel and adventure genre, which included castaways, abductions, piracy, legends of cannibals and the city of the Amazon, etc. John Coetzee There is also marked metafictionality and selfreflexivity in the text which deals with questions of language, writing, reality and fiction. John Coetzee Although Foe does not deal directly with the South African situation, it is clear that the relation of colonizer-colonized is in Cruso and Friday, and also the great divide of race, inscribed by Susan Barton and Friday. “He desires to be liberated.... all his life?” (Foe p. 148) Colonial powers have thus expressed this contradiction since the very start of colonization over 500 years ago, until this very day. John Coetzee The text it is clearly a postmodern/postcolonial text, and this is reflected in highly ambiguous plots, time is also ambiguous (1702:?75), there are several modes of narrations (letters, diary, oral narration), plus numerous intertextual allusions (Morrison’s “spoken the unspoken” Foe 141 or Derrida on writing and speech: Foe 142-143) The very title of the text is already an intertextual and ambiguous play of meanings. Coetzee diverges considerably from the original text (some fragments during part I of the text), and invites the reader to an intertextual activity (the double coding). John Coetzee A fundamental alteration of the original story consist in making Cruso a secondary figure by the introduction of Susan Barton: he does not tell the story, as it is the case in the original, but Susan Barton is the narrator who brings the story to Foe (Foe 7, 9, 11, 14, 26, 38, 40, 45: Mr. Foe) The introduction of Susan Barton dissolves the centre of masculinity of Robinson Crusoe Friday is another substantial alteration: he is not an aboriginal but African, and mute. John Coetzee By Friday being an African allows us to see Foe as a reflexion on England in the XVIII century and as a metaphor for contemporary South Africa. Friday is reduced to animality, and his story cannot be told by proxy. He reflects the unbearable oppression undergone by all oppressed people who are prevented from giving the other side of the story. John Coetzee Foe is a tissue of other texts (genres)which attempts to deconstruct the grand narratives of the past (civilazation, progress, etc.) At the same time, Coetzee’s text depends, substantially on the reader’s recognition of the intertext, which has been radically transformed and therefore difficult to decode. This is why the text introduces formal markers which help the reader to find various genres present in the text. Coetzee, in a very Borgesian manner, is only the editor of a book invented and narrated by Susan Barton. John Coetzee Foe, because of these formal characteristics represent a reflexion on form, since the various ‘documents’ and genres which constitutes the narration, hardly allow to call this text a novel. What we have is a highly palimsestic text which at the same time that it reflects on form and language, it also reflects on colonization, slavery and silence. John Coetzee One of the most important formal genre markers used by Coetzee is the epistolary genre so typical in the XVIII. The first two parts are written in an epistolary style, being intended for Foe who was expected to write the whole story. The third part is a direct account of Susan Barton’s life and confrontation with Foe. The fourth part, a real narrative relay, is meant to solve the mysteries surrounding Friday, but it does not. John Coetzee This last part has two endings, both narrate Friday’s death. There is an ambiguity regarding time and space, it seems a mixture of Foe’s home, the ship wreck, and the island. Friday dies because there is no return: no country, no identity, no language. His death symbolizes the death of a whole people dispossessed and silenced. John Coetzee This goes back to a European epistolary novel tradition where the story, in order to pass as true events, must be written as a personal story, address directly the reader, and placing the reader in a very close proximity to the text. In part I, we have Susan Barton's account where she addresses a ‘you’, which at first we believe it is addressed to the reader, but later becomes Mr. Foe (Foe 7, 9, 11, 14,26, 38, 40, 45: Mr. Foe) John Coetzee She does this by parodying her intent in part II, where she writes on the road to Bristol (Foe 99), and earlier it is stated that the letters have never been sent, (Foe 72) and again, in part III it is stated that "those letters that were never read by you" (Foe 133), thus undermining the writing of the story and leaving only the narrative by Susan Barton. Parts of the novel engages in metafictional comments on writing and on the nature of storytelling in general (7, 12, 17, 40, 47, 51, 58, 67, 81-83, 86, 88-89, 99, 116122, 131, 133, 134, 140-143 (142-143). John Coetzee But the book also offers a hypothesis on the possible genesis of Robinson Crusoe, and that tackles questions of gender and race and destabilizes this famous narrative by foregrounding the masculine, white colonial discourse that shaped it, and in turn was to shape future historical events. Susan Barton’s story is from 1702, and Robinson Crusoe was written in 1719, and this suggest an interesting play of intertextuality, where Foe becomes the intertext for Daniel De Foe, and at the same time, Robinson Crusoe becomes the intertext for Coetzee.X John Coetzee Susan Barton and writing Susan Barton has a story to tell, but she cannot write it and make it public since she does not have a voice, that is why she needs Foe. Susan is the narrator of the story transmitted to us, but this story never gets written by Foe who is the only one who can provide her with a substance: “When I reflect on my story I seem to exist ....it doesn't give the substance of the truth.” (Foe 51) John Coetzee Susan and Friday represent Coetzee’s desire to tell a story without being ‘present’ in it. In the third part the correspondence is replaced by speech: Susan doubts to whom she is speaking to. (Foe 133) By speaking to him she takes control of the narrative but also doubts about her own existence if she enters into langue: “But now my all my life grows to be story and there is nothing of my own left for me. […] But now I am full of doubt. Nothing is left to me but doubt. I am doubt itself. Who is speaking me? (Foe 133) John Coetzee In part III Susan Barton refers to part I and II of the text referring to the letters that Foe never read: “‘In the letters you did not read,’ I said, ‘I told you of my conviction that, if the story seems stupid, that is only because it so doggedly holds its silence” (Foe 117). Near the end of the novel, Foe states: “In every story there is silence, some sight concealed, some word unspoken, I believe” (Foe 141). These quotations are from passages of metafictional commentary in which Susan Barton and Foe try to “make sense” of the story of the island and of Friday. John Coetzee These attempts by the characters in the novel to “make sense” of Friday reflect the reader's attempts to “make sense” of the novel as well. The interest of the story does not lie in Susan's negotiations with the author, whom she quickly suspects of thinking it is 'better without the woman' (Foe 72), nor in the tension between the historical text of Robinson Crusoe and what is presented here as the original narrative, but in the concepts of the subject that are explored, and the relation between power and language, where Susan Barton is central. John Coetzee The novel presents two opposites poles of the linguistic constitution of the subject. At one extreme we have Susan, the female castaway who is ‘silenced’ by history but who speaks and writes almost the entire novel. At the other we have the forceful presence and absence, speech versus silence, or writing as opposed to the void or blank, represented by Friday. John Coetzee Susan Barton attaches a great importance to language, nothing is more understandable than her wish to communicate her story of the island to Foe. And despite the signs she picks up that herself is disappearing from the story she is telling, that she is becoming merely a linguistic element (133) or, as she herself says, ‘a being without substance, a ghost beside the true body of Cruso’ (p. 51), she also believes to the end that she is ‘a free woman who asserts her freedom by telling her story according to her own desire’ (Foe 131). John Coetzee She starts to worry, that the powers of language, the constrains of narrative, will suppress her, but Foe dismisses this fear of the powers of language with the familiar disclaimer that words as such are merely empty signs. What matters is who possesses the voice to speak. The paradox of being a subject constituted in language is, in Barton’s case, her desire to exist in language and take possession of her own personal history, and this leads to a loss of a sense of self, and ultimately, in the world outside this particular text, to her complete suppression. John Coetzee Language is treacherous: once you truly become a subject in language it betrays and silences you, and this is why she says: “Be attentive to yourself as you write and you will mark there are times when the words form themselves on the paper de novo, as Romans use to say, out of the deepest of inner silences”. (Foe 142-143) Earlier in the text she says: “But now my life grows to be a story and there is nothing of my own left to me. […]. Nothing is left to me but doubt. I am doubt itself. Who is speaking me? (Foe 133) John Coetzee The text demonstrates that becoming a subject in language involves a subjection to discourse. It highlights the dangers that lie in speaking ‘for’ the ‘other’ instead of letting him or her speak, as the language used for representing ‘other’ constantly seems to betray intended meanings and is an instrument of power rather than an innocent mediator of truths. It quietly but insistingly tells us that he who does not speak is not ‘dumb’. John Coetzee Friday’s Silence Is the most obvious link that conveys an almost unbridgeable gap between races and cultures. The failure of communication is conveyed most clearly by Coetzee through the language of music. Friday’s silence makes us aware that language, although an instrument of self-expression, is also a tool of oppression when that language is the language of the oppressor. John Coetzee Coetzee does not deprive Friday of expression, since his silence is expression, or rather the impossibility to have a voice both in history and in the present. Coetzee cannot speak for Friday, and this is yet another reason why Friday does not speak, and if Coetzee would have chosen to make him speak he would have engaged in a representation which he, Coetzee, refuses to provide. John Coetzee Language is identity, and this is why also Friday refuses to speak, since speaking the language of the oppressor does not allow him to express his identity and that of his story, which would remain untold. Susan Barton states: “All my efforts to bring Friday to speech, or to bring speech to Friday, have failed”. (Foe 142) John Coetzee The only power Friday has is his silence and Foe is fully aware of his resistance: “Friday has no command of words and therefore no defence against being re-shaped day by day in conformity with the desires of others […]. No matter what he is to himself... what he is to the world is what I make of him.” (Foe 121-22) John Coetzee The silence is a refusal to be represented, but because of its silence he can be represented at will. (Foe 121122) Friday's refusal to acquire language can be read as a metaphor for the fact that white colonialists never listened to the people they subjected. Friday is merely a sytlistic ‘double’ to Susan’s gender; both are speechless because they are not heard. John Coetzee The fact that Coetzee takes his cue from feminist discourse and includes the possibility that Friday’s missing tongue is perhaps only a metaphor for ‘a more atrocious mutilation’, leaving us to wonder whether ‘by a dumb slave [we are] to understand a slave unmanned’ (Foe 119), only reinforces that impression. How can the privileged white writer give voice to the black person without falling into the trap of speaking ‘for’ him? Would not that be perfectly in line with the old colonial maxim that ‘they cannot represent that themselves, they must be represented?’ (Said, 1978: 21). John Coetzee Friday’s silence is a deliberate act in the text, which comes from a white writer who realizes that any voice he will give to the Black man will necessarily sound false. John Coetzee Difference and Alterity Foe, the very title of the of the text suggests issued related to post-colonial aspects of difference and alterity. It exposes the the difficulties in reconciling the idea of belonging to a nation with the wish to express singular cultural identities and differences. In rewriting Foe Coetzee cast light on the deep forces that have driven a voice from the ‘periphery’ or ‘edge’ of the imperial world to engage in open and dialectic conflict with the voice of the ‘centre’. John Coetzee By reworking Robinson Crusoe it becomes the battle ground for the conquest of identity and difference. It is a place where the struggle between the I and the Other is ignited. For instance, Susan Barton manages to find a voice, an outlook, a way of her own to tell her story. When this happens, Foe leaves the scene and in the end it is Susan who writes of her adventures on Cruso’s island. John Coetzee In this way, the old Subject (Defoe, the Western novel, the myths of the cultural supremacy of the white race, the male, power-based relationships between mater and slave) is displaced by the Other. However, it would be disingenuous to think that the question of alterity and difference is to be resolved by substituting the ‘centre’ with the ‘periphery’ or the ‘margin’. It is not this what happens in Foe. Here, there is an attempt to create a notion of marginality (and thus of alterity) that differs from then prevailing one. John Coetzee The ‘margin’ in Foe’s characters is not a space of marginalisation but, rather, one of resistance; a space for creativity in which the binary ‘colonised/coloniser’ is put under erasure and overwritten by a plurality of multiple subjects. The idea of marginality constructed from an ‘uscentred’ vision disappears. With it disappears the image of a ‘them’ solely considered as food and sustenance for the identity and integrity of ‘us’. John Coetzee To choose the margin is a political act. As bell hooks, the African American writer, points out, to speak, write and place oneself in the margin does not mean to withdraw into marginality. Hooks: I am located in the margin. I make a definite distinction between that marginality which is imposed by oppressive structures and the marginality one chooses as site of resistance – as location of radical openness and possibility. This site of resistance is continually formed in that segregated culture of opposition that is our response to domination. John Coetzee We come to this space through suffering and pain, through struggle. We know struggle to be that which gives pleasures, delights, and fulfils desire. We are transformed, individually, collectively, as we make radical creative space which affirms and sustains our subjectivity, which gives us a new location from which to articulate our sense of the world.