Rawls* Theory of Justice

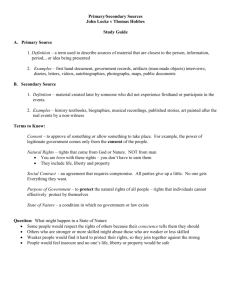

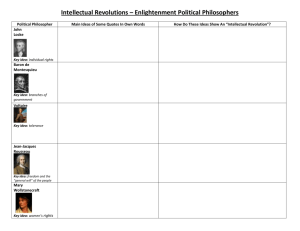

advertisement

January 20, 2011 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. Liberalism Social Contract Theory Locke, Liberalims Social Contract and Natural Law Locke on Property Utilitarianism and Intuitionism Justice as Fairness – general conception Principles of Justice, Rules of Priority John Locke, John Rawls and Robert Nozick are liberal theorists, they thus present liberal theories of justice. Liberalism describes a continuum of views ranging from libertarianism to welfare liberalism. Liberalism is a political philosophy, it is connected to a moral outlook and a particular take on justice. In its common or every day use the term means different things in different contexts – many in Australia think about the Liberal Party (the right of our political spectrum), in the US they often associate liberal outlooks with the Democrat party, the Left of the political spectrum. We are using it in a technical sense, it describes a broad political theory that has been central to mainstream politics in the US, Britain and Australia since (at least) the Declaration of Independence. Liberalism, as the name implies, is a political view based around liberty or freedom (N.B. here freedom does not imply metaphysical freedom but rather liberty). The good/just society is one that maximises freedom, unnecessary infringements on liberty are always require moral justification – political acts have a moral limit. For many the political negation of freedom is only ever justified if it is done in the name of a greater freedom than that which is negated (e.g., hate speech). Liberalism is also concerned with equality: freedom is something all are equally entitled to. There is an intersection between the values of freedom and equality in liberal philosophy (N.B., Dworkin puts great emphasis on equality) But both values, liberty and equality, can be understood in different ways: Is liberty a freedom from oppression, in which case the state might have no duty to ensure liberty can be meaningfully used (such as a society with freedom of press but where the majority of people are illiterate due to a lack of public education). Or is there a duty for the state to provide both freedom from oppression and facilitate its meaningful use (such as a society with both freedom of press and good public education ensuring the literacy through which people could meaningfully benefit from it). What about equality, is this equality of opportunity, establishing the ground rules for fair competition, without correcting for disadvantages within the competition or worrying about its outcomes; or does equality require some consideration, over and above rules, of the resources the players have at their disposal and of the way the outcomes impact on the players? How can political authority be seen as compatible with the fundamental value of freedom and equality? Any legitimate political authority must derive from the free consent of the governed, such consent is best understood as being derived from the idea of a contract or mutual agreement between free and equal contractors, whereby the governed freely surrender certain freedoms so as to gain the benefits of mutual cooperation. We restrict a volatile natural freedom in the name of a more stable civil and political freedom. Political authority is born of the contract, it is the authority to compel us to do as we have already rationally agreed we ought to do in order to enjoy a more stable form of freedom and equality. There are two elements to social contract theories: 1. they begin with an account of an ‘initial situation’, this is a description of a pre-contract situation, this situation is generally either overtly hostile (such as with Hobbes) or fraught with various inconveniences (such as with Locke), these constitute a problem that will be resolved through a contract. The type of institutional structures that appear justified will depend on the features of the initial situation that we seek to alleviate: 2. social contract theories offer a description of the contractors which emphasises that these contractors are: a) self-interested and b) rational. So, we start with rational and self-interested agents in a position, the initial situation, that is either hostile or inconvenient. a) b) c) Political authority legitimately curtails freedom because: Such curtailment is the product of consent - we freely agree to it; It is rationally limited to what is necessary to alleviate us from the problems of the ‘initial situation’ and there is reciprocity between the contractors, no sacrifices more than their peers and no one gains any more than their peers. Thus the coercive authority of the state is just. Locke is a liberal thinker whose political theory is based in social contract theory. Locke understands political power as the power of making laws (regulations that limit freedom) and executing penalties. This is done to preserve the life, liberty and property of the members of the polity. Thus political power is used for the public good. Locke begins with a conception of an ‘initial condition’ a pre-contract condition out of which the ‘social contract’ emerges. Locke terms this the “state of nature”. The earth has been given to all mankind, it is a common good that, in its untouched state, all of us have an equal claim on (equality 1). In this condition there exists a perfect equality (equality 2) derived from our freedom to do as we please without reference to the will of any other person (liberty 1) – note our equality is based in our equal freedom to do what we please. We are all equally endowed with reason (equality 3) and from this we derive the rational understanding not only that we have a right to life, liberty and property but that we may not harm our neighbours, we may not deprive them of liberty nor interfere with their possessions. Furthermore we understand that we have a right or liberty to punish (liberty 2) those who transgress our life, liberty or possessions In the state of nature we might be pre-political but we are not pre-moral – what would the status of law be in such a state? Well, if we are positivists we might suggest that without political authority there can be no law, we might say being pre-political the state of nature is also pre-legal. On the other hand, and from the perspective of a natural lawyer (closer to Locke) we might say that because the condition is not pre-moral, because we can identify clear moral imperatives vis-à-vis liberty, life and property, then there is a natural law in such a condition. Locke realises that in the state of nature law is a difficult matter – we can recognise a natural law but how do we implement it, how do we hold one another to it, who judges its breach and the penalties for its breach. The state of nature is a state of inconvenience: without an impartial arbiter (magistrate) disputes can never really be settled and so become a source of social discord. This means that our life, liberty and property are never secure. Thus we are inclined to form into political societies and institutional structures with the power to make laws and settle matters where there is some contestation over issues of right – particularly as regards life, liberty and property – in a manner that is fair to both parties. Our natural rights might be based on moral principles that are pre-political, but the fair application of those moral principles requires political institutions. The exact nature of Locke’s position in regard to property is subject to debate. Here I will initially stick with the general account found in the work of James Tully. If, as Locke claims, the earth and all things on it have been given by God to all equally, then this would seem to require that all property should be held in common. Private property seems to deny equal access to a good that is held in common. The question is: how does Locke move from the assertion that the earth is given to all equally to a justified claim to private property? While the earth is given to all in common there is a certain class of objects that are subject to an exemption - the rational human being. Locke argues that “every man has a Property in his own Person” each human being is a self-proprietor, they own themselves. Furthermore each human being not only owns their body but also, because they own their bodies, they own the productive capacities of their body (labour). When a person mixes their productive capacities, or labour, which they own, with things that are un-owned (common) these things become their property – e.g. picking an apple. There are some rational limits to this process: I can only proceed to appropriate nature (the great common) to myself as properly “at least where there is enough, and as good left in common for others”. Robert Nozick rejects Tully’s interpretation of Locke on property, he rejects the idea that property is had by mixing. When we mix what we own with what we do not, why should we think we gain property instead of losing it? For Nozick this model is not the right way to understand Locke, the proper understanding or Lockean property must be based on a “workmanship model.” We gain property because we transform nature in accordance with a rational plan. Damaging my property damages my plan and frustrates my goal. Utilitarianism: justice is best served by taking that course of action which creates the greatest overall utility or the greatest sum of utility. Intuitionism: for properly constituted human beings their intuitions tell them where the moral good lies. 1. 2. 3. “all social primary goods – liberty and opportunity, income and wealth, and the bases of self-respect – are to be distributed equally unless an unequal distribution of any or all of these goods is to the advantage of the least favoured”. Has the structure of an imperative Links justice to fair distribution of social goods Systematic conception of priorities. Principle 1: Each person is to have an equal right to the most extensive total system of equal basic liberties compatible with a similar system of liberty for all. Principle 2: Social and economic inequalities are to be arranged so that they are both – a) to the greatest benefit of the least advantaged, and b) attached to offices and positions open to all under conditions of fair equality of opportunity. Priority rule 1 (The Priority of Liberty): The principles of justice are to be ranked in lexical order (that is, the first principle takes priority over the second principle) and therefore liberty can only be restricted for the sake of liberty. Priority rule 2 (The Priority of Justice Over Efficiency and Welfare): The second principle of justice is lexically prior to the principle of efficiency and to that of maximizing the sum of advantages; and fair opportunity is prior to the difference principle.