A Hard Shove for a 'Nation on the Brink'

advertisement

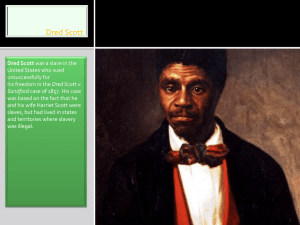

A Hard Shove for a “Nation on the Brink”—The Impact of the Dred Scott Case by Lisa Cozzens America in 1857 was, as Kenneth Stampp put it, "a Nation on the Brink." Relationships between the Northern and Southern states had been strained for decades, but during the 1840's and especially the 1850's, the situation exploded. The Compromise of 1850 served as a clear warning that the slavery issue, relatively dormant since the Missouri Compromise of 1820, had returned. As territories carved out of the Mexican cessions of 1848 applied for statehood, they stirred a passionate and often violent debate over the expansion of the South's "peculiar institution." Proslavery and antislavery forces clashed frequently and fatally in "Bleeding Kansas," while the presidential election of 1856 turned ugly when southern states threatened secession if a candidate from the antislavery Republican party won. Into this charged atmosphere stepped a black slave from Missouri named Dred Scott. Scott's beginnings were quite humble. Born somewhere in Virginia, he moved to St. Louis, Missouri, with his owners in 1830 and was sold to Dr. John Emerson sometime between 1831 and 1833. Emerson, as an Army doctor, was a frequent traveler, so between his sale to Emerson and Emerson's death in late 1843, Scott lived for extended periods of time in Fort Armstrong, Illinois, Fort Snelling, Wisconsin Territory, Fort Jessup, Louisiana, and in St. Louis. During his travels, Scott lived for a total of seven years in areas closed to slavery; Illinois was a free state and the Missouri Compromise of 1820 had closed the Wisconsin Territory to slavery. When Scott's decade-long fight for freedom began on April 6, 1846, he lived in St. Louis and was the property of Emerson's wife. The famous Scott v. Sandford case, like its plaintiff, had relatively insignificant origins. Scott filed a declaration on April 6, 1846, stating that on April 4, Mrs. Emerson had "beat, bruised, and ill-treated him" before imprisoning him for twelve hours. Scott also declared that he was free by virtue of his residence at Fort Armstrong and Fort Snelling. He had strong legal backing for this declaration; the Supreme Court of Missouri had freed many slaves who had traveled with their masters in free states. In the Missouri Supreme Court's 1836 Rachel v. Walker ruling, it decided that Rachel, a slave taken to Fort Snelling and to Prairie du Chien in Illinois, was free. Despite these precedents, Mrs. Emerson won the first Scott v. Emerson trial by slipping through a technical loophole; Scott took the second trial by closing the loophole. In 1850, the case reached the Missouri Supreme Court, the same court that had freed Rachel just fourteen years earlier. Unfortunately for Scott, the intervening fourteen years had been important ones in terms of sectional conflict. The precedents in his favor were the work of "liberal-minded judges who were predisposed to favor freedom and whose opinions seemed to reflect the older view of enlightened southerners that slavery was, at best, a necessary evil." By the early 1850's, however, sectional conflict had arisen again and uglier than ever, and most Missourians did not encourage the freeing of slaves. Even judicially Scott was at a disadvantage; the United States Supreme Court's Strader v. Graham decision (1851) set some precedents that were unfavorable to Scott, and two of the three justices who made the final decision in Scott's appearance before the Missouri Supreme Court were proslavery. As would be expected, they ruled against Scott in 1852, with the third judge dissenting. Scott's next step was to take his case out of the state judicial system and into the federal judicial system by bringing it to the U.S. Circuit Court for the District of Missouri. In entering the federal judicial system, the Scott case underwent a metamorphosis that would prove to be very important at the conclusion of the case. Most evident was the change in the defendant. Mrs. Emerson had moved to Massachusetts and remarried, leaving Scott and his case to her brother, John F.A. Sanford, still living in St. Louis. Also, the Scott v. Emerson case in the state judicial system was clearly a genuine suit between two parties; each side's purpose was to win the case. The same cannot be said of Scott v. Sandford. "Dred Scott v. Sandford," wrote Don Fehrenbacher, "was either a genuine suit, or a counterfeit designed for abolitionist purposes, or part of a proslavery plot that succeeded." This uncertainty over the true purpose of the case later made Republican charges that the case was a conspiracy designed to help the expansion of slavery even easier to believe. Whatever the true intents of the two parties were, they met in 1854 in the United States Circuit Court. Judge Robert W. Wells, "a slaveholder who nevertheless regarded slavery as a barrier to progress," presided over the trial. Sanford's first strategy was to prove that Scott was not a citizen of Missouri because he was the descendant of African slaves, but Wells ruled that because he resided in Missouri, Scott was enough of a citizen to be able to bring suit in a federal court. Sanford then used the same line of reasoning that had worked in front of the Missouri Supreme Court, arguing that even if Scott had gained his freedom while residing in Illinois, he had regained his slave status upon returning to Missouri. This defense proved successful once again, and the jury decided in favor of Sanford. The next step for Scott was to take his case to the highest tribunal in the country, the United States Supreme Court. Before he did so, however, he needed to find a suitable attorney. Fortunately, Montgomery Blair--a Missourian himself, a highly respected lawyer in Washington, and a supporter of the Free Soil party--agreed to take Scott's case without expecting payment. The Supreme Court first heard the case of Scott v. Sandford in early 1856, but ordered a reargument for the next term, perhaps because a decision would have come on the eve of the 1856 presidential election and would have forced each candidate to agree or disagree with the Court on a highly volatile issue. This would not be the last time politics intruded on the Dred Scott case. Until it came before the Supreme Court, Scott's case had not attracted much attention, either public or within the other branches of government. By early 1856, however, Congress had renewed the debate over Congressional power to regulate slavery in the territories in light of the bloody conflicts in Kansas. Both sides began to view the issue as a decision for the Supreme Court, and not for Congress, to make. As Senator Albert G. Brown, a Democrat from Mississippi, said on July 2, 1856: My friend from Michigan [Senator Lewis Cass] and myself differ very widely as to what are the powers of a Territorial Legislature - he believing that they can exercise sovereign rights, and I believing no such thing; he contending that they have a right to exclude slavery, and I not admitting the proposition; but both of us concurring in the opinion that it is a question to be decided by the courts, and not by Congress. A few weeks later, Abraham Lincoln, a Republican from Illinois agreed: I grant you that an unconstitutional act is not a law; but I do not ask, and will not take your [Democrats'] construction of the Constitution. The Supreme Court of the United States is the tribunal to decide such questions, and we will submit to its decisions; and if you do also, there will be an end of the matter. "When reargument [of the case] before the Court began on December 15," wrote Kenneth Stampp, "the potentially broad political significance of the case had become evident, and public interest in it had increased considerably." Indeed, "by Christmas 1856, Dred Scott's name was probably familiar to most Americans who followed the course of national affairs." When the Court met for the first time since the reargument to discuss the case on February 14, 1857, it favored a moderate decision that ruled in favor of Sanford but did not consider the larger issues of Negro citizenship and the constitutionality of the Missouri Compromise. The majority chose Justice Nelson as the writer of a decision that avoided these important but highly controversial issues, and Nelson went to work on it. When Nelson presented his opinion to the majority, however, he discovered that his "majority" opinion turned out to be the opinion of only himself. The Court elected to throw out Nelson's decision and instead chose Chief Justice Roger B. Taney as the writer of the true majority opinion for the court, an opinion that would include everything under consideration in the case, including Negro citizenship and the constitutionality of the Missouri Compromise. According to Justice Catron, one of the members of the majority, "the court majority. . .had been `forced up' to its change of plan by the determination of [Justices] Curtis and McLean to present extensive dissenting opinions discussing all aspects of the case." The majority decided that if the dissenters covered all the issues, they must also. Ironically, the two most antislavery justices may have forced a more proslavery opinion than what the majority originally planned to decide. By mid-February 1857, many well-informed Americans were aware that the conclusion of the Scott v. Sandford case was close at hand. President-elect James Buchanan contacted some of his friends on the Supreme Court starting in early February; he asked if the Court had reached a decision in the case, for he needed to know what he should say about the territorial issue in his inaugural address on March 4. By inauguration day 1857, Buchanan knew what the outcome of the Supreme Court's decision would be and took the opportunity to throw his support to the Court in his inaugural address: A difference of opinion has arisen in regard to the point of time when the people of a Territory shall decide this question [of slavery] for themselves. This is, happily, a matter of but little practical importance. Besides, it is a judicial question, which legitimately belongs to the Supreme Court of the United States, before whom it is now pending, and will, it is understood, be speedily and finally settled. To their decision, in common with all good citizens, I shall cheerfully submit, whatever this may be. Just two days after Buchanan's inauguration, on March 6, 1857, the nine justices filed into the courtroom in the basement of the U.S. Capitol, led by Chief Justice Taney. Taney was almost 80 years old, always physically feeble, and even weaker as a result of the effort he had put forth to write the two-hour-long opinion; therefore, he spoke in a low voice that Republicans deemed appropriate for such a "shameful decision." He first addressed the question of Negro citizenship, not only that of slaves but also that of free blacks: Can a Negro, whose ancestors were imported into this country, and sold as slaves, become a member of the political community formed and brought into existence by the Constitution of the United States, and as such become entitled to all the rights, and privileges, and immunities, guaranteed by that instrument to the citizen? One of the privileges reserved for citizens by the Constitution, argued Taney, was the "privilege of suing in a court of the United States in the cases specified by the Constitution." Taney's opinion stated that Negroes, even free Negroes, were not citizens of the United States, and that therefore Scott, as a Negro, did not even have the privilege of being able to sue in a federal court. Taney then turned to the question of the constitutionality of the Missouri Compromise. The territories acquired from France in the Louisiana Purchase of 1803, Taney stated, were dependent upon the national government, and the government could not act outside its framework as set forth in the Constitution. Congress, for example, could not deny the citizens of the new territory freedom of speech. Similarly, Congress could not deprive the citizens of the territory of "life, liberty, or property without due process of law," according to the Fifth Amendment. Taney continued: And an act of Congress which deprives a citizen of the United States of his liberty or property, merely because he came himself or brought his property into a particular territory of the United States, and who had committed no offense against the laws, could hardly be dignified with the name of due process of law. The Constitution made no distinction between slaves and other types of property. Taney reasoned that the Missouri Compromise deprived slaveholding citizens of their property in the form of slaves and that therefore the Missouri Compromise was unconstitutional. Scott's case had one last hope: the Chief Justice could decide that Scott was free because of his stay in the free state of Illinois. Taney made no such decision, instead stating that "the status of slaves who had been taken to free States or territories and who had afterwards returned depended on the law of the State where they resided when they brought suit." Scott had brought suit in Missouri and hence he was still a slave because Missouri was a slave state. Taney ruled that the case be dismissed for lack of jurisdiction and sent back to the lower court with instructions for that court to dismiss the case for the same reason, therefore upholding the Missouri Supreme Court's ruling in favor of Sanford. The next day, Justices McLean and Curtis read their dissenting opinions, both of which ruled in favor of Scott. They immediately released the text of their decisions for publication in print, but Taney withheld his for revising until late May; the only record the public had of the majority opinion was a short Associated Press article. This gave the Republicans a decided advantage over the Democrats in the "war of words," because the Republicans had the full text of the two pro-Scott dissents, while the Democrats had to rely on simply a paragraph not even written by one of the Court's justices. The "Republican assault" began as early as March 7, the day after Taney read the majority opinion, when the New York Tribune pronounced that "The decision, we need hardly say, is entitled to just as much moral weight as would be the judgment of a majority of those congregated in any Washington bar-room." The Chicago Tribune added on March 12: We must confess we are shocked at the violence and servility of the Judicial Revolution caused by the decision of the Supreme Court of the United States. We scarcely know how to express our detestation of its inhuman dicta or fathom the wicked consequences which may flow from it . . . . To say or suppose, that a Free People can respect or will obey a decision so fraught with disastrous consequences to the People and their Liberties, is to dream of impossibilities. Democratic newspapers were as quick to defend the decision as Republicans were to assault it. On March 12, the (Washington DC) Daily Union urged the country to respect the decision and unite under it: We cherish a most ardent and confident expectation that this decision will meet a proper reception from the great mass of our intelligent countrymen; that it will be regarded with soberness and not with passion; and that it will thereby exert a mighty influence in diffusing sound opinions and restoring harmony and fraternal concord throughout the country . . . . It would be fortunate, indeed, if the opinion of that court on this important subject could receive the candid and respectful acquiescence which it merits. The Cincinnati Daily Enquirer of March 8 was not as optimistic about how the antislavery public would receive the decision: While thus anticipating a general acquiescence in the decision of the Supreme Court, it would be too much to expect that it will escape attack and censure from disappointed and embittered partisans, whose political capital and hope of office will wither before it. The withholding of Taney's decision created two major other problems. First, it created a schism between Taney and Justice Curtis, one of the dissenters. Curtis had the misfortune of being one of the youngest members of the Court, as well as a native of Massachusetts, a state Taney detested because it epitomized Northern hypocrisy over the issue of slavery. Curtis further angered Taney by requesting to see his majority decision as soon as he released it. Curtis wanted to see the text of Taney's majority opinion because many parts of his dissent tied into it. During the spring and the summer of 1857, Curtis and Taney exchanged angry letters, and by September Curtis found the situation so uncomfortable that he handed in his resignation from the Court. The second problem that the withholding of Taney's decision produced was that when he released it, he had obviously added parts that were direct replies to the dissents of McLean and Curtis. Curtis estimated that Taney had appended "upwards of eighteen pages" since he had read the decision in court and added that "No one can read them without perceiving that they are in reply to my opinion." Relationships between Northerners and Southerners were already tense, but the withholding of Taney's opinion served to further polarize the two sides. Many northerners felt that parts of Taney's decision, specifically the invalidation of the Missouri Compromise on constitutional grounds, were extrajudicial because they were not necessary for arriving at a decision in the case. They charged that after Taney had shown that Scott, as a Negro, had no right to bring a case into a federal court, he should have ended his decision, instead of going on to declare that the Missouri Compromise was unconstitutional. Taney defended his decision by saying that the Supreme Court had the right to correct all the errors committed during the Circuit Court trial, including the constitutionality of the Missouri Compromise and the question of Negro citizenship: It has been said, that as this court has decided against the jurisdiction of the Circuit Court on the plea in abatement [which decided whether or not the Court would consider the question of Scott's citizenship], it has no right to examine any question presented by the exception; and that anything it may say upon that part of the case will be extra-judicial, and mere obiter dicta. This is a manifest mistake; there can be no doubt as to the jurisdiction of this court to revise the judgment of the Circuit Court, and to reverse it for any error apparent on the record, whether it be the error of giving judgment in a case over which it had no jurisdiction, or any other material error; and this, too, whether there is a plea in abatement or not. This explanation was not satisfactory for many northerners, who became angry because Taney, by extending his opinion to include issues that did not have much of a bearing on the case, had unjustly set new precedents. Southerners, of course, stood firmly by the decision of the Court, refusing to concede that any part of Taney's decision had been extrajudicial. This disagreement led to further division between North and South. The decision placed the anti-slavery Republicans in a very difficult situation. They had the choice of either agreeing to honor the decision, implying an acceptance of slavery, or refusing to respect it, which would go against the Constitution's definition of Supreme Court's decisions as the "law of the land." Not surprisingly, Republicans found ways to discount the opinion without disrespecting it outright, usually by reasoning that the declaration of the unconstitutionality of the Missouri Compromise was not law. One of their main arguments was that after Taney, speaking for the Court's majority, had decided that Scott was not a citizen and therefore did not have the right to be in a federal court, anything else he said was obiter dictum and therefore not law. Although this conceded the Democrats a small victory in upholding the non-citizenship of Negroes, this argument threw out the Court's ruling that the Missouri Compromise was unconstitutional, a major victory for the Republicans. One writer of the time declared that "the members of the most ultra school of that [Republican] party . . . admit, that the question of the citizenship of persons of African descent was the only question authoritatively decided, in the case of Scott." Following a similar line of reasoning, Republicans also argued that a judicial majority had not decided on the unconstitutionality of the Missouri Compromise and that therefore it was not law. George Curtis, one of Scott's attorneys, argued that” . . . it appears that six of the nine judges expressed the opinion that the [Missouri] Compromise Act was unconstitutional. But, in order to determine whether this concurrence of six in that opinion constitutes a judicial decision or precedent, it is necessary to see how the majority is formed . . . . If . . . the judicial function of each judge who held that the Circuit Court was without jurisdiction [because Scott, as a Negro, was could not be a citizen of the United States] . . . was discharged as soon as he had announced that conclusion, and given his voice for a dismissal of the case on that grounds, then all that he said on the question involved in the merits was extrajudicial, and the so-called "decision" is no precedent. Republicans also attempted to portray the decision as a proslavery conspiracy, one that included members of the Supreme Court. J.T. Brooke noted in his analysis of the case that "it has been repeatedly alleged that the Dred Scott decision was a `got-up case,' contrived by interested politicians to secure a judicial decision of a political question." Many Republicans noticed a brief intercourse at Buchanan's inauguration between the President and the Chief Justice, who administered the oath of office, and took that as a sign of a conspiracy between the executive and judicial branches. Senator William H. Seward, a New York Republican, noted in a widely distributed speech that Scott "had played the hand of a dummy in this interesting political game." Senator William Pitt Fessenden, a Republican from Maine, declared that” . . . what I consider this original scheme to have been, was to assert popular sovereignty in the first place with a view of rendering the repeal of the Missouri compromise in some way palatable; then to deny it and avow the establishment of slavery; then to legalize this by a decision of the Supreme Court of the United States, and claim that it had become established. I sincerely believe that decision of the Supreme Court of the United States was a part of the programme. Some more radical Republicans simply invalidated the entire decision. One writer went so far as to say after the case had been decided that the question of Negro citizenship "never has been judicially decided by any court of competent jurisdiction." Statements such as this, however, generally "surprise[d] even Republicans." Democrats, unwilling to let these Republican proclamations go unchallenged, mounted a strong defense of their own, especially in response to the conspiracy charges. Senator Judah P. Benjamin of Louisiana refuted Senator Fessenden's argument in a speech to President Buchanan: Senator [Fessenden] . . . says the Constitution does not recognize slaves as property, nor protect them as property, and his reasoning, a little further on, is somewhat curious . . . . Nothing but my respect for the logical intellect of the Senator from Maine [Fessenden] could make me treat this argument as serious, and nothing but having heard it myself would make me believe that he ever uttered it. As for Senator Seward's cries of conspiracy, Senator Benjamin simply asked to see the facts that proved these charges: This man [Taney] has been charged by the Senator from New York [Mr. Seward] with a corrupt coalition with the Chief Magistrate of the Union. He charges in fact . . . that the Supreme Magistrate of the land and the judges of our highest court, and the parties to the Dred Scott case, got up a mock trial; that they were all in common collusion to cheat the country . . . . What are the facts? Men should be a little careful in making such accusations as these; unless, indeed they care not whether they be true or false . . . . Democrats also sought to depict Republicans as anti-Constitutional because they refused to completely submit to the decision of the Supreme Court, even though the Court's decision, according to the Democrats, had been entirely within their jurisdiction as defined in the Constitution. Stephen Douglas especially used this technique to vilify Abraham Lincoln during their debates in Illinois in 1858: Mr. Lincoln goes for a warfare upon the Supreme Court of the United States, because of their judicial decision in the Dred Scott case. I yield obedience to the decisions in that court--to the final determination of the highest judicial tribunal known to our constitution. The Dred Scott decision served as an eye-opener to Northerners who believed that slavery was tolerable as long as it stayed in the South. If the decision took away any power Congress once had to regulate slavery in new territories, these once-skeptics reasoned, slavery could quickly expand into much of the western United States. And once slavery expanded into the territories, it could spread quickly into the once-free states. Lincoln addressed this growing fear during a speech in Springfield, Illinois on June 17, 1858: Put this and that together, and we have another nice little niche, which we may, ere long, see filled with another Supreme Court decision, declaring that the Constitution of the United States does not permit a State to exclude slavery from its limits. . . . We shall lie down pleasantly dreaming that the people of Missouri are on the verge of making their State free, and we shall awake to the reality instead, that the Supreme Court has made Illinois a slave State. For many Northerners who had remained silent on the issue, this very real possibility was too scary to ignore. Suddenly many Northerners who had not previously been against the South and against slavery began to realize that if they did not stop slavery now, they might never again have the chance. This growing fear in the North helped further contribute to the Civil War. Four years after Chief Justice Taney read his infamous Scott v. Sandford decision, parts of the proslavery half of the Union had seceded and the nation was engaged in civil war. Because of the passions it aroused on both sides, Taney's decision certainly accelerated the start of this conflict. Even in 1865, as the long and bloody war drew to a close with the Northern, antislavery side on top, a mere mention of the decision struck a nerve in the Northern Congress. A simple and customary request for a commemorative bust of Taney, to be placed in a hall with busts of all former Supreme Court Chief Justices, was blocked by the Republican-controlled Congress. Charles Sumner, the leader of those who blocked the request, had strong words on the late Chief Justice and his most notorious decision: I speak what cannot be denied when I declare that the opinion of the Chief Justice in the case of Dred Scott was more thoroughly abominable than anything of the kind in the history of courts. Judicial baseness reached its lowest point on that occasion. You have not forgotten that terrible decision where a most unrighteous judgment was sustained by a falsification of history. Of course, the Constitution of the United States and every principle of Liberty was falsified, but historical truth was falsified also. . . . Clearly Scott v. Sandford was not an easily forgotten case. That it still raised such strong emotions well into the Civil War shows that it helped bring on the war by hardening the positions of each side to the point where both were willing to fight over the issue of slavery. The North realized that if it did not act swiftly, the Southern states might take the precedent of the Scott case as a justification for expanding slavery into new territories and free states alike. The South recognized the threat of the Republican party and knew that the party had gained a considerable amount of support as a result of the Northern paranoia in the aftermath of the decision. In the years following the case, Americans realized that these two mindsets, both quick to defend their side, both distrustful of the other side, could not coexist in the same nation. The country realized that, as Abraham Lincoln stated, "`A house divided against itself cannot stand.' . . . This government cannot endure, permanently half slave and half free." Scott's case left America in "shocks and throes and convulsions" that only the complete eradication of slavery through war could cure.