Assessing Skills 1 - National Union of Teachers

advertisement

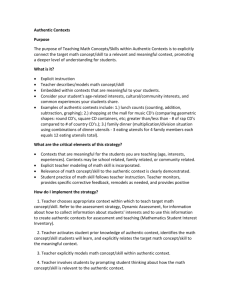

Section 3 Assessing Skills There are three key questions here: • How do we know whether or not a skill has been developed? • How do we know how well skills have been developed? • Against what measures can skills be assessed? © Curriculum Foundation 1 So, how do we assess skills? We suggested earlier that the best way was to observe them being deployed. Prof Laura Greenstein of the University of Connecticut advocates what she calls “authentic learning” that provides contexts within which assessments of “mastery” can take place. Assessing 21st Century Skills A Guide to Evaluating Mastery and Authentic Learning 2012 Corwin Books http://books.google.co.uk/books?hl=en&lr=&id=uHWu_pPEPiUC&oi=fnd&pg=PR1&dq=assessing+21st+century+skill s+laura+greenstein&ots=u2BGDqqkor&sig=yvSYadAxTsWMZpDOPn_kwrTn9M#v=onepage&q=assessing%2021st%20century%20skills%20laura%20greenstein&f=false © Curriculum Foundation 2 ‘Mastery Learning’ is often linked to a ‘competency’ approach, and Brian Male (In the two “Curriculum Design Handbooks” – see below for the reference) suggested that in this context a competency is “the ability to apply knowledge with confidence in a range of situations”. This implies the use of skills to apply knowledge, so progression to the higher (or deeper) levels of learning can be seen as developing skills within the context of knowledge. (Do remember the ‘Tree’ from the Bridging Unit?) © Curriculum Foundation 3 Lorna Greenstein sees ‘authentic learning’ as being located in a real or realistic setting, so that learning is not just abstract and theoretical but meaningful to the learner in their own context. These settings then become the contexts within which skills can be deployed and so assessed. Without the authentic setting, assessment is not so valid. Authentic learning and ‘authentic assessment’ are part of a world-wide movement. © Curriculum Foundation 4 Sheila Valencia is Professor of Education at the University of Colorado. Her 1993 book ‘Authentic Reading Assessment’ is interesting in that one might have thought that reading is always located in its own setting anyway. It is skills like problem solving that might vary greatly from setting to setting, and when you really have to solve a problem in real life, then it might be much easier (or harder!) than in the classroom setting. However, in Unit 3 we looked at ED Hirsch’s research that showed that reading skills are, indeed, contextually related. So ‘authentic’ learning and assessment are really important. © Curriculum Foundation 5 The key point here is that if we want to assess skills – be they subject skills or more generic ‘21st Century’ skills – then the best approach is to observe those skills being deployed. The more authentic the situation in which they are deployed, then the more valid the assessment is going to be. Laura Greenstein’s point is that if skills are learned in an authentic setting , then they will be able to be deployed in an authentic setting. This is not just an assessment point. If we want our students to be able to apply their skills in real life, then we need to make our learning contexts as close as possible to those real-life situations. Hence ‘authentic’ learning and assessment. © Curriculum Foundation 6 This still leaves us with the issue of what we are measuring skill performance against. How do we know how good the performance is when we see it? There are two separate approaches here: • A skills ladder • Contextual performance Of course, you will already have set learning objectives in your planning and these will be your key assessment criteria. © Curriculum Foundation 7 Did you notice this ladder by the way? What do you think it is based on? Doesn’t it look a bit like Bloom’s Taxonomy that we looked at in the Bridging Unit? You will be familiar with this approach. It takes a particular skill and imagines what the progressive levels might be. This then acts as a rubric or marking scheme, and so adds some structure and reliability to what would otherwise be a subjective judgment. The issue is the extent to which we get these levels right, or whether there really are distinct levels, or whether skills can be considered (or even exist) outside of the context in which they are deployed. © Curriculum Foundation 8 Do you remember ED Hirsch suggested that skills are always contextually related and that it is impossible to create a skills ladder that does not take account of the context in which the skill is deployed? For example, the way you carry out an investigation in science is different from the way you investigate in history. Yet investigation is a skill. The ability to think critically (another skill) depends upon having sufficient knowledge of the subject you are thinking about. Brian Male argued that there is seldom a need for a skills ladder, because the increasingly complex knowledge context provides the necessary progression. © Curriculum Foundation 9 In this approach, the skill is seen as staying essentially the same, but the context in which it is deployed becomes increasingly more complex. For example, a young child can carry out investigation of rolling cars down a slope and can control the variables of slope and surface etc. Increasingly, they will be able to carry out more complex investigations (possibly ending with the Large Hadron Collider!). The skill of investigation has stayed the same (setting things up, controlling variables, drawing conclusions etc). What has changed is the level of complexity of the context in which the skill is deployed. Hirsch would argue that this applies to all skills. His research showed that even reading skills are related to the learner’s knowledge of the subject being read. © Curriculum Foundation 10 So, there are two approaches here – skills ladders or using the knowledge context as the reference point of progress. Skills ladders can be very helpful – so long as we remember that skills do not necessarily develop in such an orderly and hierarchical way. It is also useful to consider the complexity of the context as the criterion of progression. What is essential is to provide an authentic context in which the skills can be developed, and in which they can be assessed. But, how does this fit with the new national curriculum? © Curriculum Foundation 11 The national curriculum in England Key stages 3 and 4 framework document September 2013 As we noted in Unit 1, the new national curriculum is not set out in the same way for all subjects and key stages (Why not? What were they thinking of?). This inconsistency complicates matters. However, let’s start with an example from Key Stage 3 Mathematics in the new curriculum. At this Key Stage, there is a “Working Mathematically” section. Firstly, look at the sort of verbs that start each bullet point of this section (consolidate, select, substitute etc). Are these looking for knowledge, understanding or skills? © Curriculum Foundation 12 © Curriculum Foundation Yes, they are all skills. Knowledge But what about the progression? Is there any ‘skills ladder’ here? Do we have to develop our own skills ladder? Understanding Or can we use the knowledge context? Skills To do that, we need to look at the ‘Subject Content’ section of the new programmes: © Curriculum Foundation 14 © Curriculum Foundation You can see that this is not set out hierarchically, so does not provide a progression of knowledge (or ‘increasingly complex contexts’) in which the skills can be deployed. However, as Brian Male pointed out (Male 2012) skills develop in terms of the range of contexts in which the learner can deploy them, as well as in the complexity of those contexts. What the new national curriculum is giving us here is a range of contexts. © Curriculum Foundation 16 Increasing range of contexts Increasing complexity of contexts © Curriculum Foundation 17 However, if we go back to the second bullet point of the Maths skills list (slide 41) it says: “select and use calculation strategies to solve increasingly complex problems.” So the increasing complexity of contexts is clearly being seen as important to progression. However this increasing complexity is not provided by the new national curriculum. This is being left to schools. And what schools need to provide in order to promote and assess progression is not a skills ladder but a hierarchy of increasingly complex contexts. (So, no problem there, then!). But we are given the range! © Curriculum Foundation Before we go on to what schools should do, look again at the ‘Subject Content’ section of the KS3 Maths (no need to go back – its on the next slide). Look at the verb at the beginning of each bullet point. What do you notice? © Curriculum Foundation 19 © Curriculum Foundation Yes, even the ‘Subject Content’ section is written mainly in terms of skills (use, interpret and compare, order ..). There is one “understand” and nothing that is pure knowledge. This is also the case for Maths in KS 1 & 2. But not in Science, as we shall see later. © Curriculum Foundation 21 Do you remember that: The national curriculum in England Key stages 1 and 2 framework document September 2013 The national curriculum in England Key stages 3 and 4 framework document December 2014 • In Maths and Science there are specifications for the end of each year from Y1 to Y6, and at the end of the key stage KS3 and Sothen this model works forforMaths KS4 Within those varied at KS3, but there what about the approaches, are two key • In English there are end of year specifications subjects and Key forother Y1 and Y2, then specifications for differences with regard toLower the Primary (end of Y4) and Upper Primary (end Stages? of Y6), then at the of the key stage for . specification end of subject skills KS3 and 4 • For all other subjects, there are only end of key stage specifications. © Curriculum Foundation 22 The national curriculum in England Key stages 1 and 2 framework document September 2013 The national curriculum in England Key stages 3 and 4 framework document December 2014 All other subjects are set out differently Science has a “Thinking Scientifically” anyway. There are much more general section at all key stages. specifications that are not contentspecific. Maths has a “Thinking Mathematically” section at KS3 only For example here is the entire programme of study for Key Stage 2 English does not have a corresponding Music. section – but the “Aims” at the beginning of each key stage set out Look at the verbs – what is being asked corresponding skills. for? © Curriculum Foundation 23 © Curriculum Foundation So, we have sets of skills set out for: So model of range and complexity • the Science atincreasing all key stages works well for all subjects – but we have to look in •different Maths at Key Stage 3 places to find the skills information that we need. (Who decided to set it out like this? Is it English at Key Stages 2 & 3ofand Maths at really intentional? Which1,theory history do we use here: conspiracy theory ot the for other Key Stagethe 1& 2 have sets of –‘Aims’ each one? key stage that essentially set out subject skills. The assumption in this Unit is that KS4 assessment will be based on GCSE criteria. We shall look at In allseparately. other subjects, they are within the EYFS programmes of study at all key stages. © Curriculum Foundation 25 In sense, these subjects easier Theone model that we explored in theare context of because progression is work set out yearwell by within year a working across a year, will equally year for the English Maths 2. across keyand stage. It inis KS1 onlyand necessary to assess against the set criteria. Let’s look again at the way English, Maths and Science are set out. Here are the aims for KS2 However, this does not enable us to assess English. progress within a year. © Curriculum Foundation © Curriculum Foundation