Netflix and the Anarchical Revamp of Television By: Alan Fu Advisor

advertisement

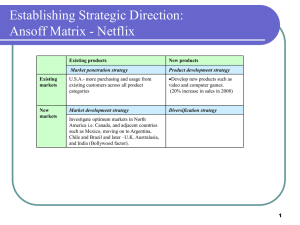

Netflix and the Anarchical Revamp of Television By: Alan Fu Advisor: Richard Linowes, Kogod School of Business For: Honors in Business Administration Completed: Spring 2015 2 Abstract: This report explores Netflix’s strengths and weaknesses in a rapidly diversifying industry of home entertainment. Netflix currently leads the U.S. as the most popular video subscription service at over 40 million subscribers. However, incoming competitors with deep pockets such as Amazon and with vast production expertise like HBO and Hulu test Netflix’s hold on the world of digital TV, while financial challenges in the form of massive upfront content licensing fees, sometimes at millions of dollars per episode for mere reruns, are a cause for concern as digital rights values soar. As U.S. subscribership reaches a saturation point, Netflix looks to international expansion for new growth opportunities, recently announcing the goal to be in 200 countries by the end of 2016. Netflix has financed this expansion with $1.5 billion in senior notes this past February, but with international margins expected to be negative for the next two years, it is crucial that Netflix maintains the profitability and stability of the U.S. subscriber base. In order to sustain domestic growth, Netflix should partner with Kickstarter to build a new branch of original crowdfunded content with independent filmmakers. Meanwhile, providing its millennial-heavy subscriber base with more comedy options and an expanded branch of relatable minority characters will solidify Netflix’s reputation as a consumer-centric entertainment hub. 3 April 30, 2015 FROM: Alan Fu, Young People Consulting TO: Reed Hastings, CEO, Netflix CC: Ted Sarandos, Chief Content Officer, Netflix; Greg Peters, Chief Streaming and Partnerships Officer, Netflix; Richard Linowes, Assistant Professor, American University RE: Pursuing Consumer-Centric Innovation Executive Summary Netflix has not only revolutionized entertainment, it has spurred a linear TV counter-culture. By giving users the power to dictate television to their schedules rather than vice-versa, Netflix is breaking the upfront advertising model that has been the precedent of TV broadcasting for five decades. As the first-mover in video streaming subscription services, this former exclusively DVD-by-mail service has enjoyed a rapid growth in subscriptions over the past few years. However, competitors with large financial war chests like Amazon, and traditional networks with proven production capabilities like HBO have begun adapting to Netflix’s monthly subscription model. Concurrently, inflated licensing fees have made Netflix’s role as a pure distributor unsustainable, so the company now produces original content to create lasting value and differentiation within this new flagship platform of home entertainment. U.S. subscriptions may stagnate in a few years, and Netflix plans on tapping into international markets for growth opportunities. The international expansion is aggressive, with the hope of having the VOD service operational in 200 countries by the end of 2016. Consequently, Netflix plans to repurpose a sizable chunk of the U.S. marketing budget to help raise awareness of its brand overseas, yet this cannot excuse Netflix to rest in the U.S. where competition is fiercest. 4 The streaming experience of Netflix has been effective because it is consumer centric: viewing histories personalize recommendations, the digital library stays open 24/7, and users watch however long they want, completely free of advertisements and distractions. Yet the innovative never sleep, and Netflix should launch a crowdfunding program for independent show creators, boost its level of original comedy content, and connect minority audience members with relatable onscreen characters to bring the consumer power of choice beyond the viewing experience and into the production process. Background With 57.4 million subscribers at the end of 2014, Netflix is the U.S. leader in video-on-demand streaming services. The online entertainment platform was established in 1998 when current CEO Reed Hastings created a DVD mailing service designed to make home video rental hasslefree (Netflix, Company Overview). After several years of losses and grinding price wars against video giant Blockbuster, Netflix finally emerged victorious. Rental stores became obsolete, Blockbuster went bankrupt, and Netflix’s convenient by-mail delivery combined with its personalized queue system made it the new cornerstone for home video consumption. Netflix shipped its billionth DVD on February 25th, 2007, and steady growth seemed promising (Roettgers). However, CEO Hastings realized that without innovation, Netflix would share the same fate as Blockbuster. So early in 2007, Netflix introduced streaming, bringing full movies to the computer. The concept was so new that a research analyst for Wedbush Securities thought Hastings “was nuts.” 5 The stream service initially offered a limited library of 1,000 movies that were considered to be bottom-of-the-barrel disasters (Reed Hastings Revealed). Nonetheless, streaming was a companion service for all DVD subscribers, so it was free. As infrastructure made the Internet more accessible and higher bandwidths a standard, Netflix’s streaming services took off. Netflix began to offer streaming plans only, and the company signed licensing agreements with Starz, Dreamworks Animation, Relativity, AMC, CW, and other studios. By the end of 2011, Netflix had twice as many streaming subscribers as DVD subscribers. Today, Netflix has market penetration in 50 countries and is available on virtually any entertainment device from the laptop to the game console (Spangler, “Netflix Wants…”). To combat the costly strategy of licensing content from other providers, Netflix has begun launching its own. One of Netflix’s premiere series, House of Cards, was launched in February 2013 to critical acclaim. Six months later, Orange is the New Black broke gender roles and gained a massive cult following. These shows prove that Netflix is no one-trick pony—it has the resources and talent to produce great content and deliver it. The Battle of Fees TV shows, movies, and documentaries are the intangible products of Netflix’s business model. Unfortunately, with the increasing customer preference for streaming, studios have ensured that licensing fees nearly keep pace with revenues. In 2014, Netflix earned $5.5 billion in revenue, yet it reaped only $267 million in profits. Netflix’s content licensing obligations total up to $9.4 billion, nearly twice the annual revenue of 2014. 6 Although Netflix’s DVD subscriber base is shrinking, the company enjoys a higher profit margin from that segment. The contribution margins from DVD subscribers were 48% in 2013 and 2014, while the margins for domestic streaming customers were only 27% in 2014 and 23% in 2013. Non-U.S. streamers provided a contribution margin of -12% in 2014, an improvement from the margin of -39% in 2013 (Netflix, Form 10-K). In the DVD rental model, the only upfront cost is in the DVD purchase. Netflix buys a few thousand copies of movie “X” and recuperates costs within a handful of rentals of each DVD. On the other hand, for digital rights of movies and TV shows Netflix usually pays a fixed fee over a certain number of years, and these costs are massive. According to The Hollywood Reporter, Epix made a deal which gave Netflix access to 1,000 films from Paramount, MGM, and Lionsgate for $200 million per year. This was more than the $175 million Showtime television offered Epix for their movie package, signaling to the entertainment world that digital rights hold greater perceived value than TV rights. In addition, Netflix dished out $45 million to Disney for the six seasons of Lost alone (Bond). The costs seem even more inflated after considering that Netflix’s licensing deals are NOT for first-run syndication. Each TV show and movie is a rerun—it’s premiered somewhere else first, and with the only revenue coming from monthly subscriptions of $7.99, it takes a large inflow of new customers to cover the annual expenses of a single content license. Despite these costs, Netflix does not plan to slow down content acquisition and estimates it will spend an additional $6 billion on content over the next three years. As new competitors like Amazon, Hulu, and HBO increase their presences in the Video-On-Demand (VOD) marketplace, the demand for digital licensing rights will go up, bringing prices with them. 7 Crowded Competition At peak periods, Netflix accounts for a staggering 35% of all U.S. downstream traffic on the Internet. Meanwhile, the leading social media platform in the world, Facebook, receives only slightly more than 2% of total U.S. downstream traffic (“Global Internet Phenomena Report”). Netflix’s market penetration is impressive with 40 million domestic subscribers who watch an average of 93 minutes a day (Spangler, “Netflix Subs”). However, media firms like HBO and Hulu, as well as retail giant, Amazon, have noticed. HBO, the world’s most popular subscription service with a customer base of 114 million strong, has elected to move forward with HBO Now, a standalone version of HBO Go, allowing users to stream from anywhere and cut the cord (Bachman). The service came out just this April, rolling out in correspondence with the season 5 premiere of its most popular show, Game of Thrones. The streaming service offers access to every episode of HBO’s shows, but unlike Netflix, the library contains more than previously aired seasons. The service works like a broadcast subscription, for full episodes of current seasons are uploaded to HBO Now on the same day as the live premiere. HBO Now has been set at a premium price point of $14.99, but HBO’s 14-year streak as the most Emmy-nominated network in television has solidified its brand reputation as the frontier of scripted content. HBO Now currently offers 30 day risk-free trails, so the world’s largest cable subscriber base may only be getting bigger. Amazon, the largest online store on the planet, has recently expanded its “instant video” service to include approximately 3,500 unique movies and TV shows at any given time. Amazon instant 8 video has been gaining traction and doubled its use of domestic U.S. bandwidth in the past 18 months. However, Amazon has to tackle the challenge of optimizing its online interface because unlike Netflix or Hulu, the company’s web infrastructure was not built from the ground up for streaming. The instant video service still doesn’t provide closed captioning for many of its shows, and the quality of the stream deteriorates on mobile devices. Not one to be deterred, Amazon has begun an original content division of its own, and it just earned its first Golden Globe on the quirky comedy series, Transparent. Meanwhile, to enhance the viewer experience Amazon has announced plans to provide High Dynamic Range (HDR) video by the end of 2015, as well to add more ultra-HD or 4K quality shows. A serious threat is the potential partnership of HBO with Amazon. HBO inked a deal in January 2015 with Amazon to offer unlimited streaming access to previous seasons of award-winning shows like True Blood, Boardwalk Empire, and The Sopranos (Lieberman). The deal also permits Amazon Fire TV owners to use the HBO Go streaming app, meaning they can freely watch HBO shows on Fire TVs (as long as they have HBO subscriptions). This was the first licensing deal HBO has ever done for a streaming service and may be a sign of joint efforts with Amazon in the future. Hulu is the smallest but most direct competitor of Netflix. Hulu is the only streaming company to offer a free version of its service. A user must upgrade to a paid subscription called Hulu Plus to be granted full access to the video library. The free version simulates an indefinite trial, permitting viewers to browse without commitment, albeit with limited options. Hulu Plus is only $7.99 a month, and Hulu doesn’t plan to change that anytime soon since it is the only paid streaming service to accept advertisers. Advertisements in the side panels of the display, and even product placements within the show help cover the expenses for Hulu’s licensing fees and 9 original content production. While other streaming companies may refuse to give into sponsorships to avoid disrupting the viewer experience, this additional revenue stream gives Hulu the flexibility to sustain a very competitive price point. Target Market A recent Mintel study found that less than half of all U.S. adults had watched video on a subscription-based streaming service in a one-month period. However, for 18 to 34-year-olds, that figure jumped to 71%. Mintel also uncovered that Netflix had more than triple the domestic subscribers of any other VOD streaming service, and more than 55% of 18 to 34-year-olds said they watched something on Netflix at least once in the one-month period. From these results, it appears that millennial professionals and college students are at the heart of Netflix’s massive market share. Besides age, there were four demographic traits with noticeable differences in favorability of streaming services: gender, race, parental status, and household income. Males were more likely than females to consume video streaming content, and they were more likely to be frequent users. About 46% of males were medium (3 to 5 TV shows or movies per week) or heavy (6 or more episodes or movies per week) users of streaming services compared to 35% of females. Minority consumers demonstrated a higher average likelihood to utilize streaming services than their Caucasian counterparts. This coincides with movie theater attendance as well. While the majority of respondents who identified as Black, Asian or Hispanic consumed streaming video at 10 least once in a one-month period, only 42% of Whites said the same. An underlying factor could be the younger population of minority groups, but minorities have generally shown early adoption patterns in consumer technology and a heavier usage of entertainment media in the past few years. Parents with children under 18 years of age also show a significantly higher chance of being heavy users of video streaming subscriptions. It could be that parents with younger children find Netflix and other streaming sites to be a convenient way to entertain their family. A night in with Netflix is also a cheaper substitute to a night out. Consumers with mid-tier household incomes, specifically between $75,000 and $99,999, had the highest subscription rate of paid streaming services at 56% (Hulkower). This particular income level gives them flexibility to subscribe to multiple streaming services at once, and the low monthly payment plans for these services have become attractive alternatives to the expensive costs of a-la-carte models in cable on-demand and digital store rentals and purchases. Challenges Original Content Hollywood’s studios aggregate their leverage to attain every possible dollar in distribution deal, squeezing operating margins to low profitability levels. In the meantime, video streaming is not patent-protected, and companies like Crackle who offer completely free content or Paramountbacked Epix who deliver movies straight from the studio are beginning to disrupt the stability of 11 streaming distribution channels. These factors have provoked Netflix, Hulu, and Amazon to transition from content distribution to content creation. Although content licenses may be expensive, they will never surpass the financial undertaking and risk involved with original content production. Netflix’s powerhouse political series, House Of Cards, cost $100 million for the first two seasons at more than $3.8 million per episode (Greenfield). HBO’s signature series, Game of Thrones, tallies at about $6 million per episode, and one season’s expenses are similar to a big budget feature length film. In contrast, the most expensive show ever licensed was Sony Pictures TV Blacklist at $2 million per episode (Andreeva). Netflix and its competitors are investing heavily in new content because original series build brand equity and guarantee exclusivity. Standard licensing deals last for up to 5 years but are often less, and even in the best case scenario when shows become popular, distribution rights may have to be shared. Content is king, and the company that controls the content controls the bargaining process. Unsatisfied with their subordinate role, streaming companies are now devising their own supply chain of shows to secure stable long-term rights without having to be at the mercy of Hollywood executives. Original content isn’t an obvious fiscal choice. A well-received series like House of Cards may gain additional subscribers, but it may not be enough to offset the immense costs of production. However, original content is an important step towards sustainable advantage. The medium of streaming is not a sustainable advantage; a cable or tech company could offer a faster, more reliable streaming service in the near future. The race is on to build an exclusive library of must- 12 see shows so when streaming competition peaks, consumers will have a reason to stay with Netflix. If Netflix can generate iconic shows, it will anchor itself as a centerpiece of mainstream culture, and consumers will stop asking if Netflix is worth it and begin wondering how they ever lived without it. Genre Divide National TV audiences have been fracturing since the 1980’s. According to Nielsen ratings gathered since 1954, the average primetime television broadcast viewership has dropped steadily over the past two decades for each of the major four networks: NBC, ABC, CBS, and Fox (The Cancel Bear). Even the most popular broadcast shows of today like the drama musical Empire and the nerdy sitcom The Big Bang Theory often don’t break 10 millions viewers—a ratings level that would likely be the lowest acceptable floor for primetime shows of the 70’s and 80’s (Maglio). The drop in ratings is not from deterioration in the quality of the TV content but from the numerous choices now available to the consumer. In a 2015 joint study done by National Association of Television Program Executives (NATPE) and the Consumer Electronics Association (CEA), 56% of respondents agreed that there are more quality television programs to choose from, while 67% of respondents agreed that there is more variety in television programs than there have been in the past. The number of hours an average American spends watching television hasn’t changed; what’s changed is the medium. In 2013, Americans watched 147 hours of TV and 4 hours of online video per month, but in 2014, Americans watched 141 hours 13 of TV and 11 hours of online video per month (Luckerson). While Americans are locked into a routine of about five hours of video per day, their eyes will be switching screens. Not all genres are created equal. In movies, when each genre has to fight a battle royale for the highest honor of best picture, dramas dominate The Academy Awards, and 89.1% of Oscars winners from 1928 to 2010 were classified as at least partially dramas. AMC’s Breaking Bad ushered in an era of prestige drama television that has enraptured audiences with big budget special effects, complex character narratives, and feature-film style cinematography. Critics seem to agree, with dramas composing 70% of the top ten annual spots in Metacritic’s aggregate critic rating system since 2010 (Bettinger). The two most-watched on cable television are Game of Thrones and The Walking Dead, each averaging tens of millions of viewers. However, all of this prestige has come at a price—dramas also boost the biggest budgets of any genre around. With the average drama pilot episode tallying at $5.5 million and headliners like Game of Thrones tallying between $6 million and $8 million per episode, producing a season for one of these shows involves expenses roughly equivalent to a Hollywood feature (Nathanson). A-list talent is noticing the rise of reputation in TV drama, and traditionally exclusively movie actors like Kevin Spacey, Vince Vaughn, Matthew McConaughey, Kevin Bacon, and Woody Harrelson have flocked to feature as leads in shows like True Detective, House of Cards, and The Killing. This newfound star power will give the TV drama lasting appeal, yet it also means continually rising payrolls. Comedy isn’t quite as sexy, and it doesn’t pack the same critical wallop. Compared to dramas, films classified as full or partial comedies are underwhelming performers in the best picture category, earning just 16.9% of best picture Oscar nods from 1928 to 2010 (Bettinger). 14 Recent critical reception of TV comedies hasn’t fared better either, with comedies earning only about 22% of the top 10 spots in Metacrtic’s annual rankings since 2010. Comedies also seem to be trending out on network television, as two of the big four networks, NBC and ABC, have cut the total number of their original running comedy series by nearly half, while the other two, Fox and CBS have kept this number stagnant (Team TVLine). However, there may be a silver lining out there—comedies are not dead. Eight of the top ten rated shows on broadcast television may indeed be dramas, but the very top two, The Big Bang Theory and Modern Family, are both comedies (Maglio). There is also a production advantage to comedies, for they are short-form, 30 minutes or less, and require less special effects and high-quality set pieces than the typical drama. In fact, the low production quality of a comedy is often used to amplify its humor like in the case of Tim and Eric Awesome Show, Great Job! and other sketch shows where the campiness is part of the joke. These savings can stack up with the average broadcast comedy pilot episode tallying at about $2 million, almost one-third of the typical drama (Nathanson). Better yet, there is definitely a demand for humor, as NATPE found that millennials want to laugh--77% of millennials stated that comedy was a regularly watched TV genre, making comedy the leading genre over movies, news, reality, and even drama. The same study discovered that millennials with SVOD subscriptions were still more likely to watch comedy regularly on their streaming service than any other genre, but only 71% of millennials stated that they watched comedy on SVOD. As mentioned earlier, video streaming services are most popular amongst 18 to 34 year olds, so original comedy series have noteworthy potential in building attractiveness of SVOD portfolios in the near future, especially with the decline of the broadcast comedy. 15 Operating Margins The television industry is a tough place to earn money with just content alone, and that’s why television networks resort to advertising and sponsorship to earn around one-third of total revenues (Media Partners Asia). Netflix however has taken a resolute stand against advertising and interfering with the user experience. The lack of this additional revenue stream has hurt Netflix’s profitability, and the company has struggled to keep its operating margins above 10% (Netflix, Form 10-K), which is near the bottom when compared to either content-creating studios or major distributors. Although Netflix’s $8.99 subscriptions have created undeniable value to millions of consumers, these prices require sales projections to be highly accurate, and they provide little wiggle room for investments through retained earnings. Cash flow is also a problem, and Netflix has seen its cash flow growth fall behind net income growth for the past three years. Noticing this deficit in cash, Netflix issued $1.5 billion in senior notes in February 2015, with $700 million due in 2022 at 5.5% and $800 million due in 2025 at 5.875% (Financials – Netflix, INC.). This massive financing initiative has made investors wary; Moody’s has dropped Netflix’s bond rating from “Ba3” to “B1,” while S&P has slashed its rating from “BB-minus” to “B-plus,” digging deeper into junk bond status (Spangler, Updated). All of this debt pushed Netflix’s traditionally equity-to-debt ratio of two to one to below one for the first time in company history. Running on primarily debt will only push interest expenses higher and squeeze operating margins even thinner, so Netflix must find a way to compensate to stay afloat. 16 A few of Netflix’s original series such as House of Cards and Orange is the New Black have gained worldwide followings and near universal brand awareness. Yet there are troubling signs of fiscal efficiency in the average Netflix show. Fixed asset turnover has shot up ever since 2009, meaning that the plant, property, and equipment (namely Netflix’s headquarters in Burbank and its DVD distributor centers) have generated revenues more efficiently with every passing year. On the other hand, the total asset turnover ratio, which for Netflix is mostly non-tangible assets in the form of content licenses, has gone down steady since 2010, and it was less than one in 2013 and 2014 (Financials – Netflix, INC.). If Netflix is to be a pioneer of home entertainment, it cannot sustain a business model where the value of its content licenses exceeds its total revenues. Netflix must either boost subscriptions fees, add advertising revenue or cut expenses in licensing contracts in order to become profitably viable within the next three years. Net Neutrality As the single largest user of bandwidth in the United States, Netflix has been clogging traffic for Internet Service Providers (ISP’s) at peak times. When the popularity of Netflix soared in 2013, Comcast let Netflix’s customers suffer the brunt of slowdowns, and other ISP’s followed. Netflix began rallying public support for net neutrality and tried to find alternate solutions. It began channeling data through Cogent, an internet network that had indirect access to Comcast’s customers, and spent $100 million developing open connect appliances (OCA’s) that could localize up to 90% of Netflix traffic to internet points of presence, effectively reducing streaming distances to the last, local mile (Seward). Cogent was soon running at capacity, and Comcast refused to accept the appliances without a per gigabyte fee. Then December brought the holiday season to U.S. video streaming, clogging playback quality to below standard definition 17 for many users. Customers backlashed and condemned Netflix for neglecting its service. With no victory in sight, Netflix paid an undisclosed amount to Comcast on January 2014 to create a direct pipeline between Netflix’s content servers and Comcast’s broadband network. Agreements with Verizon and other ISP’s followed. These payments were labeled as “peering fees.” However, Feburuary 2015 saw the FCC vote three to two in favor of strong net neutrality rules. The ruling squandered the Time Warner and Comcast merger, and until these rules are offically appealed, any ISP can be condemned for using service speed as leverage for payment (Edwards). This was a victory for Netflix in future negotiations over Internet speed, but unfortunately, Netflix must still honor the agreements made with Comcast and other ISP’s until they expire. International Vision At 40 million domestic subscriptions, Netflix is approaching the saturation point within the U.S. market, especially because the multi-screen policy of its plans allows subscriptions to be shared among households. Netflix considers itself a “global internet TV network” and has announced a plan to be in 200 countries by the end of 2016. This is a rapid acceleration of Netflix’s previous target of 200 countries by the end of 2017. Overseas adoption of the service has been faster than anticipated—the first quarter of 2015 set a personal company record of 2.43 million new international subscribers. Initial international expansion was conservative with just Canada in 2010. Since then, Netflix has been aggressive—but with mixed results. Although Netflix’s first wave of international markets—Canada, Latin America, Scandinavia, Finland, Sweden, Netherlands, Ireland, and the 18 United Kingdom were profitable as a group by the end of 2014, some countries were pulling the weight for others. Europe in particular has seen quick acceptance because of large bandwidth availability and a pro net neutrality infrastructure, while Latin America has been sluggish due to low broadband penetration and scarcer levels of disposable income. Nonetheless, Netflix intends on being the world’s largest international TV provider and aims for 80% of its revenue to come from non-U.S. subscribers by the end of expansion. There are unique barriers for each country—for example France has a 36 month minimum delay between VOD release and theatrical release (Spangler, “Netflix Wants”). Even as Netflix pushes for a one-size-fits-all pricing at $8.99 per month, not everyone is getting the same product. Half of Europe isn’t receiving Lost or Mad Men; France subscribers don’t even have access to Netflix’s signature series, House of Cards, because local channel Canal Plus has obtained French Rights (Heyman). Each foreign market is home to local competition and poses a risk in currency exchange fluctuations. However, the biggest question is how much Netflix must customize their localization efforts by country. Europe TV viewership is more fragmented than the United States, and audiences tend to be more nationalistic in their content choices. German and French audiences in particular are used to consuming American movies and TV shows that are dubbed, not subtitled, and Netflix must decide if these language adjustment costs are worth paying. Netflix hopes to launch in China in the coming months, but strict government regulations and censorship may be difficult to bypass without a local partner. Plans are already in place for Netflix to enter its first Asian country, Japan, this fall. Japan boasts the largest number of 19 broadband connections outside of the U.S. and Germany, but xenophobia and the dominance of local culture forced competitor Hulu to sell its Japanese headquarters in 2014. Recommendations: To help finance the expansion, Netflix must count on the profitability of its established domestic subscriber base. In order to raise revenues in pace with expenses, Netflix must not only retain the U.S subscriber base but also continue a stable if unspectacular level of growth. Here are three strategies to ensure that Netflix’s original content continues to evolve and impress U.S. viewers. 1. Netflix Independents with Kickstarter A renaissance movement is underway, for many television shows are no longer conceived within studios but are extracted directly from consumer preferences. Netflix’s algorithm is currently its most sustainable advantage—it finds what users want to watch before they even know it. Netflix records what shows users watch, what they stop watching, even what they scrolled through, and it builds customized libraries that serve these implicit tastes. Consumers should also be able to explicitly state what they want to watch, and this can be done through voting. Amazon Prime Instant Video has been dishing out several pilot episodes in batches so that users can vote on which ones should be produced into series. Although this has generated interest in Amazon Prime Instant Video, pilots are typically the most expensive 20 episode in a show’s production history, and these show concepts were still created without any audience consent. In Netflix Independents, the power to choose is fully transferred to the consumer. Through talent agencies, guilds, and independent amateurs alike, Netflix finds and receives thousands of pitches annually. Because of financial constraints, only a select few series are produced each year, and some unique show concepts never come to fruition. Netflix Independents, a partnership between Kickstarter, the most popular crowdfunding organization in the world, and Netflix, will post TV show pitches that don’t make the cut but show exciting potential. These pitches will be jointly available on Netflix’s website and Kickstarter’s website, and both parties will be able to accept donations. Kickstarter is an ideal partner to help Netflix enter the independent filmmaking market because it attracts close to 1 million unique U.S. users a month and has earned project pledges from 8,453,000 different people. Over its six-year history, Kickstarter has raised over $274 million on film and video alone (“Stats,” Kickstarter). What Netflix brings in a millennial powerhouse distribution channel, Kickstarter brings in creativity and legal protection from the crowdfunding process. The average comedy pilot averages at around $2 million, and the average drama pilot averages at around $5.5 million (Nathanson). The combined crowdfunding of Netflix’s 60 million plus subscriber base and Kickstarter’s devoted supporters can turn these TV pitches into reality. While Kickstarter infuses its inspirational DIY brand reputation, Netflix will provide the platform to amplify the voices of these independent filmmakers. A Netflix Independent candidate will 21 post his or her TV series pitch on the Netflix and Kickstarter websites and ask for the amount of money needed to create the first two to five episodes. Pitches will be limited to about three minutes because Kickstarter analytics have discovered that successful campaign videos averaged around three minutes and five seconds. Campaigns will be run for 35 days (again, the optimal length for a Kickstarter campaign), and if the show creator meets his or her goal by the deadline, he or she will earn a distribution contract from Netflix for that first mini-season. If a campaign is not successful, all money raised will be returned to the supporters. This contract will also give Netflix the option for the right of first refusal after the first season. Independent filmmakers will use funds provided to produce their show for the designated number of episodes and also to send rewards to the backers based on the amounts donated. When the show premieres, Netflix will then assess overall viewership, critical reception, and production quality and decide whether or not to renew the show for a second season and beyond. If a show is renewed, Netflix will agree to pay a fixed licensing fee that covers the show’s budget in return for the exclusive right to premiere the show. If a show is not renewed, the show’s creators are free to take their concept and the rights of season one to any producer and distributor of their choosing, but Netflix can retain season one in its library for a set number of years. This partnership allows Netflix not only direct access to a new pipeline of original content, but it also gives them the flexibility to avoid the high upfront costs of pilot episodes. As mentioned earlier, pilot episodes are often the most expensive of a show’s production history, but they also have a failure rate. Less than half of pilot episodes generally make it onto the first season, and 65% of TV shows are canceled by the end of season one. Netflix will save a substantial amount 22 of capital by mitigating the risk of season one’s episodes, and this outsourced financing could drive the average content licensing costs down. Best of all, Netflix builds its brand reputation and establishes positive corporate social responsibility with this program, as the average subscriber will see that Netflix is trying to help aspiring filmmakers achieve their dreams. 2. Laughter is the key for the fountain of youth. The genre being watched most regularly is comedy. Millennials especially have a taste for it; 74% of Millennials watch comedy regularly, compared to 70% of Gen X and 68% of Baby boomers. Millennials are also the most likely to look for comedy on streaming sites, and 57% specifically stated that they go to Netflix for comedy first. Even though comedy holds such favor with audiences, composition of Netflix’s total portfolio of original series is 37% dramas, 30% kids shows, 22% comedy, and 11% other. Meanwhile, HBO’s currently running series has a composition of 66% comedy, 27% drama, and 7% documentary. Hulu offers 69% comedy, while Amazon offers 44% comedy (aggregated from HBO, Amazon, Hulu, and Netflix websites). Netflix does not need to match the extensive level of comedy in HBO’s portfolio, but it must offer more competitive amounts of original content in this genre. The primary source of Netflix’s comedy series comes from broadcast networks like NBC, ABC, and CBS. As broadcast television fades, and streaming competition increases, Netflix cannot rely on rerunning sitcoms to satiate viewers’ heavy appetites for comedy. Therefore, Netflix should aim for a minimum 23 level of 40% comedy in its portfolio. Comedy does not have to be a mutually exclusive genre, and it can be fused with drama and sci-fi elements in new and creative ways. Comedy offers a reduced production cost to drama and often can be shot faster. The shorter time frames of comedies also allow for relatively sporadic viewing that better suits college students, parents, and those with mobile lifestyles. Laughter is never out of style, and a consistent stream of original content within this fundamental genre can help Netflix retain brand loyalty among its broad subscriber base. 3. Let the viewer look in the mirror American audiences are diversifying, but Hollywood and TV have lagged behind. The entertainment industry has been predominately white, but Mintel Oxygen has found that the average African-American, Hispanic, and Asian consumes more movies and television than the average Caucasian. In addition, the 2015 Hollywood Diversity report found that TV shows that casted an accurate 31% to 40% of minorities on screen enjoyed higher aggregate broadcast and cable ratings when compared to underrepresenting counterparts. The research shows that diversity sells and buys well, yet minority representation in front of and behind the camera is scarce. Composing 17.1% of the U.S. population, Hispanics are only featured in an average of 2% of broadcast speaking roles and 3% of those roles on cable. At the same time, Asians make up 5.3% of American citizens, yet they’re only landing in 4% of speaking roles in broadcasting and 3% in cable. When minorities are actually shown on camera, they’re often shuffled into the background. Minorities are underrepresented in lead roles by a ratio of 6 24 to 1 in broadcast and 2 to 1 in cable (Hunt). Hispanics have proven to be film and TV’s most loyal demographic, and Asians are the fastest growing minority in America. This underrepresentation should be fixed, and the content creator that does it first will likely enjoy a lasting first-mover advantage. While movies tend to be plot-driven, TV shows tend to be character-driven. Audiences are drawn to TV characters that are likeable, dynamic, and most of all, relatable. This is shown by the rise of TV ensemble shows where a large number of characters hold equal importance to the plot, as opposed to the traditional structure of a one-protagonist narrative. The two most popular TV shows today, Game of Thrones and The Walking Dead have ensemble casts, and the principle applies to comedies too, with broadcast leaders Modern Family and The Big Bang Theory exploiting conflicts in their many character relationships for humor. However, Game of Thrones doesn’t have any minority representation—all its major characters are white, and the other three shows reflect significantly less than the accurate 31 to 40% minority ratio on screen. With so many important roles to fill in ensemble shows, Netflix has an opportunity to cast more Hispanic and Asian characters to accurately reflect the diversity of its viewership. Popularity of minority ensemble casts was tested earlier this year when Fox debuted Empire, a show that featured the members of a hip-hop and entertainment label, and the ratings exploded, beating out Sunday night NFL games and even dethroning ratings champion The Big Bang Theory a few times in its first season. The Empire success should serve as assurance for the future of diversity in television programming. Therefore, Netflix needs Hispanic and Asian consumers to consistently relate to characters in its original content, and their perceptions of Netflix’s brand will flourish. 25 Appendices Appendix A Total Subscription Base, U.S. and International Number of Subsribers (in millions) 120 100 80 Domestic 60 International 40 20 0 Netflix HBO Hulu Aggregated from sources from Netflix, Engadget, and Diffen. Appendix B Overview of Netflix International Content LIbraries 26 Appendix C: Pricing Number of Titles Adsupported Number of Countries 2014 awards 4K Supporte d $7.99 per month for $14.99 per month current users, $8.99 per month for new users 7200 Titles 2000 titles $99 per year $7.99 3500 titles 4150 titles No No No Yes Over 50 170 1 (USA) 1 (USA) 31 Emmy nominations (primetime) 99 Emmy nominations (primetime) 2 Golden Globe Nominations 3 Daytime Emmy nominations, 1 Sports Emmy nomination 7 Golden Globes Nominations Yes 15 Golden Globe nominations No Yes No Comparison of Streaming Services Aggregated from sources from UnoTelly, Engadget, Amazon, and Diffen Appendix D: Characteristics of Successful Crowdfunding Campaigns 27 Source: Shopify Crowdfunding Guide Appendix E Streaming Popularity among Minorities 28 Appendix F Minority Representation on Screen 29 Source: Hollywood Diversity Report: Flipping the Script Appendix G Financial Statements Income Statement Balance Sheet Statement of Cash Flows 30 Source: Netflix 2014 10-K Appendix H: Key Efficiency Ratios Source: MorningStar Financials 31 Appendix I Broadcast Viewership History Source: The Collider 32 Appendix J: Broadcast Ratings Current Source: TheWrap 33 Works Cited Andreeva, Nellie. "Netflix Acquires 'The Blacklist' For $2 Million An Episode." Deadline. N.p., 28 Aug. 2014. Web. 13 Apr. 2015. Bachman, Justin. "HBO Finally Reveals Profit Numbers. Take That, Netflix." BloombergBusiness. Bloomberg, 5 Feb. 2014. Web. 15 Apr. 2015. Bettinger, Brendan. "Cinemath: What Makes a Best Picture? A Look at Rating, Runtime, and Genre Over 80 Years of Oscars." Collider. N.p., 27 Dec. 2011. Web. 1 May 2015. Bibel, Sara. "HBO Receives 99 Primetime Emmy Nominations, The Most of Any Network This Year." TVbytheNumbers. Zap2it, 10 July 2014. Web. 9 Apr. 2015. Bond, Paul. "What Hollywood Execs Privately Say About Netflix." The Hollywood Reporter. N.p., 14 Jan. 2011. Web. 13 Apr. 2015. The Cancel Bear. "Primetime Network TV Trends 1954-2008." TVbytheNumbers. N.p., 01 Oct. 2008. Web. 1 May 2015. "A Crowdfunding Infographic: Differences Between Platforms and Best Practices for Creators." Shopify. N.p., 7 Aug. 2014. Web. 16 Apr. 2015. Edwards, Haley. "FCC Votes 'Yes' on Strongest Net-Neutrality Rules." Time. Time, 26 Feb. 2015. Web. 17 Apr. 2015. "Financials - Netflix, INC." Morningstar. N.p., 2015. Web. 22 Apr. 2015. "Global Internet Phenomena Report." Sandvine. N.p., 9 Jan. 2015. Web. 12 Apr. 2015. Gold, Jason. "Interview with Jason Gold." Telephone interview. 24 Apr. 2015. Greenfield, Rebecca. "The Economics of Netflix's $100 Million New Show." The Wire. The Atlantic, 1 Feb. 2013. Web. 14 Apr. 2015. Heyman, Stephen. "Netflix Taps Into a Growing International Market." The New York Times. The New York Times, 12 Feb. 2015. Web. 10 Apr. 2015. Hulkower, Billy. "Streaming Media: Movies and Television - US - December 2013." (2013): n. pag. Mintel Oxygen Academic. Web. 10 Apr. 2015. Hunt, Dr. Darnell, and Christina Ramón. Hollywood Diversity Report: Flipping the Script. Rep. Ralph J. Bunche Center for African American Studies at UCLA, 21 Feb. 2015. Web. 22 Apr. 2015. Lieberman, David. "HBO Signs Exclusive Licensing Deal With Amazon Prime." Deadline. Deadline Hollywood, 23 Apr. 2014. Web. 12 Apr. 2015. Luckerson, Victor. "Fewer People Than Ever Are Watching TV." Time. Time, 3 Dec. 2014. Web. 05 May 2015. Maglio, Tony. "Meet TV's Comedy and Drama Champ: Here's the Ratings Ruler Without Reality, Sports and Specials." TheWrap. N.p., 26 Jan. 2015. Web. 1 May 2015. Media Partners Asia. "Revenue of the TV Industry in the United States In 2012 and 2017, by Source." Statista. N.p., 2012. Web. 22 Apr. 2015. Nathanson, Jon. "The Economics of a Hit TV Show." Priceonomics. N.p., 17 Oct. 2013. Web. 19 Apr. 2015. NATPE, and CEA. Consumer Choice in a Dynamic TV Landscape. Rep. NATPE & CEA, Jan. 2015. Web. 21 Apr. 2015. "Netflix." Company Overview. N.p., 2014. Web. 29 Apr. 2015. Netflix. Form 10-K. Netflix Investor Relations. N.p., 29 Jan. 2015. Web. 12 Apr. 2015. 34 Ocasio, Anthony. "TV Success Rate: 65% Of New Shows Will Be Canceled (& Why It Matters)." Screen Rant. N.p., 17 May 2012. Web. 22 Apr. 2015. Reed Hastings Revealed: Bloomberg Game Changers. Prod. NIna Weinstein. Perf. MItch Lowe and John Antioco and MIchael Pachter. BloombergBusiness. N.p., 2013. Web. 14 Apr. 2015. Roettgers, Janko. "Netflix Streaming Users Now Outnumber DVD Subscribers 2:1." Gigaom. N.p., 25 Jan. 2012. Web. 12 Apr. 2015. Seward, Zachary M. "The Inside Story of How Netflix Came to Pay Comcast for Internet Traffic." Quartz. N.p., 27 Aug. 2014. Web. 1 May 2015. Spangler, Todd. "Netflix Subs Now Watch 1.5 Hours of Video Daily, Up 350% Since 2011: Study." Variety. N.p., 25 Sept. 2014. Web. 14 Apr. 2015. Spangler, Todd. "Netflix Wants the World: Can It Really Expand to 200 Countries in 2 Years?" Variety. N.p., 22 Jan. 2015. Web. 15 Apr. 2015. Spangler, Todd. "Updated: Netflix Prices $1.5 Billion in Debt to Fund Content, Other Initiatives." Variety. N.p., 02 Feb. 2015. Web. 22 Apr. 2015. "Stats." Kickstarter. N.p., 20 Apr. 2015. Web. 20 Apr. 2015. Team TVLine. "2012 Renewal Scorecard: What's Coming Back? What's Getting Axed? What's on the Bubble?" TV Line. N.p., 03 Jan. 2012. Web. 1 May 2015. Team TVLine. "2014 Renewal Scorecard: What's Coming Back? What's Getting Cancelled? What's on the Bubble?" TV Line. N.p., 31 Oct. 2013. Web. 1 May 2015. Wheeler, Gilles. "Interview with Gilles Wheeler." Telephone interview. 27 Apr. 2015. Williams-Grut, Oscar. "Netflix Passes 60m Subscribers, Plans Europe Expansion." The Independent. Independent Digital News and Media, 16 Apr. 2015. Web. 17 Apr. 2015.