Race, La Raza & Reality

advertisement

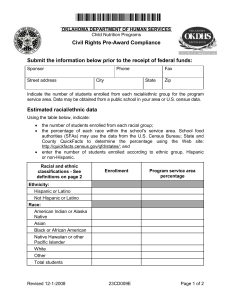

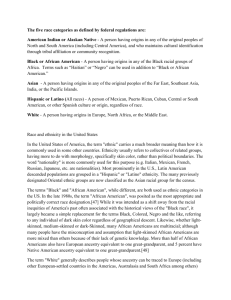

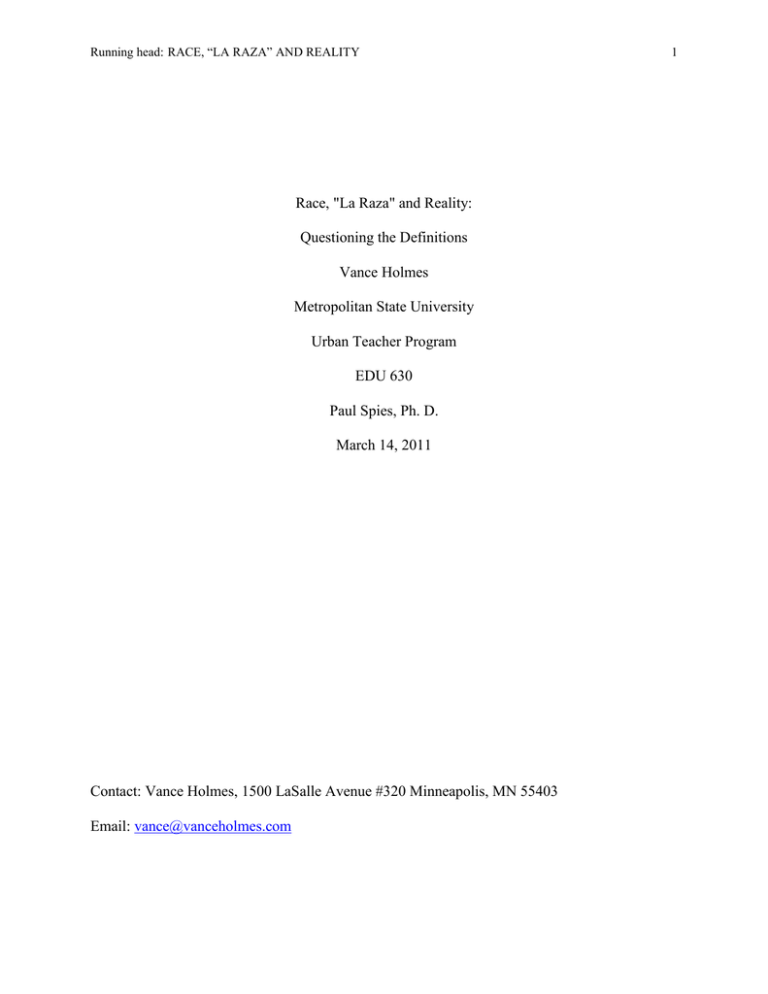

Running head: RACE, “LA RAZA” AND REALITY Race, "La Raza" and Reality: Questioning the Definitions Vance Holmes Metropolitan State University Urban Teacher Program EDU 630 Paul Spies, Ph. D. March 14, 2011 Contact: Vance Holmes, 1500 LaSalle Avenue #320 Minneapolis, MN 55403 Email: vance@vanceholmes.com 1 RACE, “LA RAZA” AND REALITY 2 Race, "La Raza" and Reality: Questioning the Definitions Were we ever a pre-racial society? Race is a relatively modern invention. Ancient societies may have classified people by religion, social status or language, but the concept of race did not always exist. As the 15th century gave way to the 16th, the concept of race took hold because it was used to justify the enslavement of Black people in this nation’s early European settlements. As the colonies grew, the ideas of race and of racial superiority evolved, and became institutionalized. The idea of race solidified as wealthy land-owning planters in early America moved from a system of indentured servitude to a system where Africans were imported and held as permanent slaves. A central defining element of America’s slavery system was that the children of a slave mother automatically became slaves. These ideas of race, though contrary to the human spirit, were nonetheless codified into law. In 1705 the first Virginia slave codes were passed, followed by similar statutes in many other areas. By 1776, the contradiction between human slavery and our founding father's ideals of freedom and human dignity, as outlined in the Declaration of Independence, were evident. Many fraudulent scientific and religiously based theories were advanced in an attempt to explain away this contradiction and rationalize the system of slavery which was economically advantageous to wealthy White landowners. From that point forward in American history, race and racial superiority would be used to similarly justify the extermination of American Indians, the exclusion of Asian immigrants, and the taking of Mexican lands. RACE, “LA RAZA” AND REALITY 3 What is race and is it real? One thing seems clear to me: the "racial" breakdowns used in sociological and educational research are suspect -- and even objectionable in many ways. Race is not real. It is a social idea and a social contruct. Human racial classifications have no basis in biology. There is no gene, characteristic, or trait that distinguishes the members of one “race” from another. Science has determined that genetic traits are inherited independently of one another -- that is, the genes for skin color have nothing to do with the genes for hair. However, it is important to say that race, as a social force, is real. Race and the effects of racial classification are embedded in our legal, educational and social institutions. What is the origin and meaning of the terms, Hispanic and Latino? Joel Spring speaks to notions of race and ethnic classification in his research on the Hispanic / Latino American experience. Spanish language use alone seems to constitute a common identity of being Hispanic or Latino, says Spring. He further states that “this identity is strengthened in struggles to gain recognition for bilingual education programs in U. S. public schools.” So perhaps part of what defines the Hispanic and Latino American experience is a culturo-linguistic struggle. Of course, Spanish is not the native language of all Hispanic and Latino peoples, since some would say that Hispanic encompasses all peoples living in America in areas not under U.S. or Canadian control. Spring finds that many people prefer Latino to Hispanic because Hispanic may be associated with Spanish cultural imperialism. Latin America, as opposed to “Spanish America,” would theoretically include all speakers of Latin-based languages. The phrase "Latin America" was popularized by Chilean author Francisco Bilbao in 1858 to differentiate between what Spring delicately describes as “the supposedly cold and rigid RACE, “LA RAZA” AND REALITY 4 temperament of Anglo-Saxons and the hypothetically warm and lighthearted souls of others living in the Americas.” Spring also investigates definitions of race in the context of the commemoration of “El Dia de la Raze (The Day of the Race) when, on 12 October 1492, Columbus landed in the Antilles.” For some, Spring says, this date represents the birth of the Hispanic people “as a new hybrid race created from a mixture of Africans, Europeans, and Native Americans.” La Raza then, means The Race or The People. The conception of La Raza, in this sense, would include most Mexican, Central American, Caribbean, and South American peoples. Spring notes that, theoretically La Raza would include descendants of enslaved Africans brought to the US who also have European and Native American ancestors. La Raza specifically would exclude from the category of Hispanic those American Indians or Native American peoples who have no African or European ancestry. How did concepts of racial identity expand? Prior to the civil rights movement of the 1960s, the courts largely defined who was Black, White, American Indian, Asian, Puerto Rican, and Mexican American. Despite slavery’s official end, throughout the 19th century the social construct of racial superiority grew and developed. Race became the justifying force behind cultural imperialism, identified by such phrases as “manifest destiny” and “the White Man’s Burden.” Then, the 1965 Immigration Act eliminated the 1924 national quota system and expanded the diversity of America’s immigrant population. Spring explains that these multiple concepts of racial identity “demonstrate how racial concepts are socially constructed in contrast to legal or administrative definitions of race.” Currently most legal-based concepts of race have vanished, but as Spring points out -- “Native- RACE, “LA RAZA” AND REALITY 5 born African Americans and whites” tend to express a definite “racial identity as Black and White.” If race is just a concept, why does our government still use racial classifications? Hispanic and Latino are confusing terms used differently by different people. The imprecise names are often meant to denote a regional or a language group. Significantly, the U. S. Census Bureau does not use a scientific definition of race for those of Hispanic or Latino origin, maintaining that racial categories are determined by “sociopolitical circumstances.” The Census Bureau ties race to ethnic origin, but the government agency emphasizes that a person’s race is determined through self-identification. According to Spring, the Census Bureau continues to use racial classification because -- as it has been throughout the history of the United States – racial classification is a requirement of U. S. government policies. The U. S. Census Bureau’s 2006 Subject Definitions state: The racial classifications used by the Census Bureau adhere to the October 30, 1997, Federal Register Notice entitled, “Revisions to the Standards for the Classification of Federal Data on Race and Ethnicity,” issued by the Office of Management and Budget (OMB). The OMB requires five minimum categories for race: American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, Black or African American, and White. Since race is a matter of self-identity, the OMB’s race categories are to be accompanied by the possibility of a person identifying as belonging to more than one race or "some other race." The following are the official definitions of racial categories from the Office of Management and Budget and the U. S. Census Bureau: RACE, “LA RAZA” AND REALITY 6 American Indian or Alaska Native -- A person having origins in any of the original peoples of North and South America ( including Central America) and who maintain tribal affiliation or community attachment. Asian -- A person having origins in any of the original peoples of the Far East, Southeast Asia, or the Indian subcontinent including, for example, Cambodia, China, India, Japan, Korea, Malaysia, Pakistan, the Philippine Islands, Thailand, and Vietnam. It includes “Asian Indian,” “Chinese,” Filipino,” “Korean,” “Japanese,” “Vietnamese,” and “Other Asian.” Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander -- A person having origins in any of the original peoples of Hawaii, Guam, Samoa, or other Pacific Islands. Black or African American -- A person having origins in any of the Black racial groups of Africa. It includes people who indicate their race as “Black or African American,” or provide written entries such as African American, Afro-American, Kenyan, Nigerian, or Haitian. White -- A person having origins in any of the original peoples of Europe, the Middle East, or North Africa. It includes people who indicate their race as "White" or report entries such as Irish, German, Italian, Lebanese, Near Easterner, Arab, or Polish. Are we now living in a post-racial society? Spring extensively quotes cultural anthropologist Sandra Lopez on the question of the existence of a post-racial society. She contends that “the United States is becoming a post-ethnic society but not a post-race one.” Although ethnic categories are increasingly difficult to define, Lopez argues, the United States is not post-racial because racial discrimination -- based mainly RACE, “LA RAZA” AND REALITY on skin color -- is still central to social relationships. “The U. S. continues to look at racial classifications in official discourse,” Lopez says, “as well as academic and public discourse.” We are certainly not a post-racial society. Race is not real. It is only ideation. But considering the very real manifestations of the concepts of race and racial superiority, and the deep history of division that has resulted from these ideas -- America will likely never be postracial. 7