Subject - Loudoun County Public Schools

advertisement

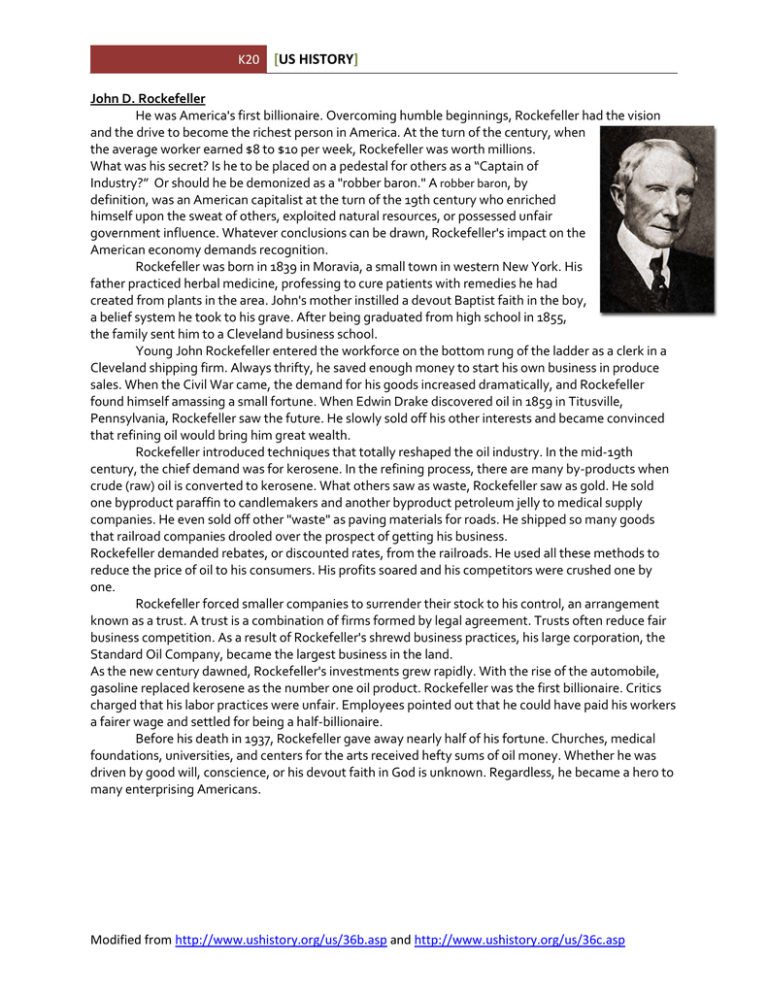

K20 [US HISTORY] John D. Rockefeller He was America's first billionaire. Overcoming humble beginnings, Rockefeller had the vision and the drive to become the richest person in America. At the turn of the century, when the average worker earned $8 to $10 per week, Rockefeller was worth millions. What was his secret? Is he to be placed on a pedestal for others as a “Captain of Industry?” Or should he be demonized as a "robber baron." A robber baron, by definition, was an American capitalist at the turn of the 19th century who enriched himself upon the sweat of others, exploited natural resources, or possessed unfair government influence. Whatever conclusions can be drawn, Rockefeller's impact on the American economy demands recognition. Rockefeller was born in 1839 in Moravia, a small town in western New York. His father practiced herbal medicine, professing to cure patients with remedies he had created from plants in the area. John's mother instilled a devout Baptist faith in the boy, a belief system he took to his grave. After being graduated from high school in 1855, the family sent him to a Cleveland business school. Young John Rockefeller entered the workforce on the bottom rung of the ladder as a clerk in a Cleveland shipping firm. Always thrifty, he saved enough money to start his own business in produce sales. When the Civil War came, the demand for his goods increased dramatically, and Rockefeller found himself amassing a small fortune. When Edwin Drake discovered oil in 1859 in Titusville, Pennsylvania, Rockefeller saw the future. He slowly sold off his other interests and became convinced that refining oil would bring him great wealth. Rockefeller introduced techniques that totally reshaped the oil industry. In the mid-19th century, the chief demand was for kerosene. In the refining process, there are many by-products when crude (raw) oil is converted to kerosene. What others saw as waste, Rockefeller saw as gold. He sold one byproduct paraffin to candlemakers and another byproduct petroleum jelly to medical supply companies. He even sold off other "waste" as paving materials for roads. He shipped so many goods that railroad companies drooled over the prospect of getting his business. Rockefeller demanded rebates, or discounted rates, from the railroads. He used all these methods to reduce the price of oil to his consumers. His profits soared and his competitors were crushed one by one. Rockefeller forced smaller companies to surrender their stock to his control, an arrangement known as a trust. A trust is a combination of firms formed by legal agreement. Trusts often reduce fair business competition. As a result of Rockefeller's shrewd business practices, his large corporation, the Standard Oil Company, became the largest business in the land. As the new century dawned, Rockefeller's investments grew rapidly. With the rise of the automobile, gasoline replaced kerosene as the number one oil product. Rockefeller was the first billionaire. Critics charged that his labor practices were unfair. Employees pointed out that he could have paid his workers a fairer wage and settled for being a half-billionaire. Before his death in 1937, Rockefeller gave away nearly half of his fortune. Churches, medical foundations, universities, and centers for the arts received hefty sums of oil money. Whether he was driven by good will, conscience, or his devout faith in God is unknown. Regardless, he became a hero to many enterprising Americans. Modified from http://www.ushistory.org/us/36b.asp and http://www.ushistory.org/us/36c.asp K20 [US HISTORY] Document #1: George Rice, “How I Was Ruined by Rockefeller,” New York World, October 16, 1898. I am but one of many victims of Rockefeller’s colossal combination,” said Mr. [George] Rice, “and my story is not essentially different from the rest. … I established what was known as the Ohio Oil Works. … I found to my surprise at first, though I afterward understood it perfectly, that the Standard Oil Company was offering the same quality of oil at much lower prices than I could do — from one to three cents a gallon less than I could possibly sell it for.” “I sought for the reason and found that the railroads were in league with the Standard Oil concern at every point, giving it discriminating rates and privileges of all kinds as against myself and all outside competitors.” Document #2: Excerpt from Ida Tarbell, The History of the Standard Oil Company, 1904. Note: Ida Tarbell was born in Pennsylvania in 1857. Her father was an oil producer whose business failed— and he blamed Rockefeller. Her brother also worked for another oil company that competed with Rockefeller. In the late 1800s, Ida Tarbell became a journalist for McClure’s Magazine, and she wrote articles criticizing Rockefeller and his business. These were later published as a book, The History of the Standard Oil Company. In the fall of 1871, [Rockefeller and some other oil refiners developed] a remarkable scheme, the gist of which was to bring together a secretly large enough body of refiners and shippers to persuade all the railroads handling oil to give to the company formed special rebates on its oil, and drawbacks on that of other people. If they could get such rates it was evident that those outside of their combination could not compete with them long and that they would become eventually the only refiners. They could then limit their output to actual demand, and so keep up prices. This done, they could easily persuade the railroads to transport no crude for exportation, so that the foreigners would be forced to buy American refined. They believed that the price of oil thus exported could easily be advanced 50%. The control of het refining interests would also enable them to fix their own price on crude. As they would be the only buyers and sellers, the speculative character of the business would be done away with. Document #3: Ida Tarbell, “John D. Rockefeller: A Character Study,” McClure’s Magazine, July 1905. But when a man deliberately decides to build up his fortunate by taking advantage of practices against which the moral sense of the day has pronounced….he must have the courage of his decision, he must be prepared to sustain his determination by any or all of those practices which are essential in supporting a deed which society declares contrary to her good. He must be prepared to conceal, to spy, to threaten, to bribe, to perjure himself, and he must be prepared to harden his heart to the sufferings of those who fall in his path. This is what it has always cost to do the thing of which the moral sense of the world disapproves. This is what it always will cost. There is no evidence that Mr. Rockefeller has ever hesitated once, in thirty-two years, at the price demanded. He has faced the need with unwavering courage. He has paid, like a man who has weighed the price of wrong-doing and decided to pay it. Document #4: Excerpt from John D. Rockefeller’s memoirs In the year 1867 the firms of William Rockefeller &. Co., Rockefeller and Andrews, Rockefeller and Co., and S. V. Harness and H. M. Flagler united in forming the firm of Rockefeller, Andrews, and Flagler. The cause leading to the formation of this firm was the desire to unite our skill and capital in order to carry on a business of greater magnitude with economy and efficiency in place of the smaller business that each had heretofore conducted separately. As time went on, we interested others and organized the Standard Oil Company, with a capital of $1,000,000. As the business grew, and more markets were obtained at home and abroad, more persons and more capital were added to the business, and new corporate agencies were obtained or organized, the object being always the same -- to extend our Modified from http://www.ushistory.org/us/36b.asp and http://www.ushistory.org/us/36c.asp K20 [US HISTORY] operations by furnishing the best and cheapest products. I ascribe the success of the Standard Oil Company to its consistent policy of making the volume of its business large through the merit and cheapness of its products. It has not only sought markets for its principal products, but for all possible by-products, sparing no expense in introducing them to the public in every nook and corner of the world. The 60,000 men who are at work constantly in the service of the company are kept busy year in and year out. Standard pays its workers well, it cares for them when sick, and pensions them when old. It has never had any important strikes, and if there is any better function of business management than giving profitable work to employee year after year, in good times and bad, I don’t know what it is. Document #5: History of the Rockefeller Foundation http://www.rockefellerfoundation.org/about-us/our-history John Davison Rockefeller embraced philanthropy early in life. In his teens, he was regularly donating money from his first job to his Sunday school and other activities of his Baptist church. As his personal wealth grew, so did his generosity. Impressed by an 1889 essay by Andrew Carnegie, Rockefeller wrote to the philanthropist, “The time will come when men of wealth will more generally be willing to use it for the good of others.” It was that year that Rockefeller began his own philanthropic work in earnest, making the first of what would become $35 million in gifts, over a period of two decades, to found the University of Chicago. In 1901 he established the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research, now Rockefeller University. In 1903 he created the General Education Board at an ultimate cost of $129 million to promote education in the United States “without distinction of sex, race, or creed.” The Rockefeller Foundation began its work in 1913 with the founder’s 39-year-old son, John D. Rockefeller Jr., as its president. The first grant, of $100,000, went to the American Red Cross to purchase property for its headquarters in Washington, DC. and for “a memorial to commemorate the services of the women of the United States in caring for the sick and wounded of the Civil War." Support for scholarship and educational opportunity—to colleges, schools, research institutions, and libraries—has been a part of the Foundation’s work in virtually every year of its existence. It supported some of the earliest and most substantial efforts to open the doors of higher education to African Americans. From supporting Peking Union Medical College and schools of public health across the globe to co-founding the Partnership for Higher Education in Africa, the Foundation has implemented positive change through the increase of knowledge. This was the genius of Rockefeller and his Foundation successors. They saw conditions that needed to change. They did their homework. They invested in cutting-edge research. They called on experts and put many of them on the payroll. When a young Albert Einstein sent a request for $500 to John D. Rockefeller's top lieutenant, Rockefeller instructed his deputy, "Let's give him $1,000. He may be onto something." They experimented, adapted, and changed course when necessary. They didn't use the word innovation then; they called it "scientific philanthropy." But innovation was their game. It was bold and daring, intrepid and risk-taking. Since its inception, John D. Rockefeller’s foundation has given more than $14 billion in current dollars to thousands of grantees worldwide. Modified from http://www.ushistory.org/us/36b.asp and http://www.ushistory.org/us/36c.asp K20 [US HISTORY] Document #6: John D. Rockefeller Political Cartoons Modified from http://www.ushistory.org/us/36b.asp and http://www.ushistory.org/us/36c.asp