Collaboration Workshop - Russ Linden & Associates

advertisement

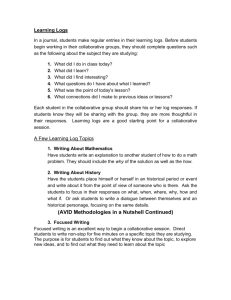

Collaborating Across Organizational Boundaries: It’s No Longer Optional Russ Linden Russ Linden & Associates www.russlinden.com; russlinden@earthlink.net “You have to learn to manage in situations where you don’t have command authority, where you are neither controlled nor controlling. That is the fundamental change.” -- Peter Drucker, management theorist, on the key leadership challenge of the future. 1 About Russ Linden Russ Linden is a management educator and author who specializes in organizational change methods. Since 1980, he has helped government, non-profit and private-sector organizations develop leadership, foster innovation, and improve organizational performance. He is an adjunct faculty member at the University of Virginia and the Federal Executive Institute. He writes a column on management innovations for Management Insights, an online column sponsored by Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government and Governing Magazine. In 2003 he was the Williams Distinguished Visiting Scholar at the State University of New York (Fredonia) School of Business. He has published numerous articles, and five books. His book Seamless Government: A Practical Guide to Reengineering in the Public Sector (Jossey-Bass, 1994), was excerpted in the May, 1995 issue of Governing Magazine, and has been translated into Chinese. His book Working Across Boundaries: Making Collaboration Work in Government and Nonprofit Organizations, is now in its 7th printing. It was a finalist for the best book on nonprofit management in 2002 (awarded by the Alliance for Nonprofit Management). His most recent book, Leading Across Boundaries, focuses on the leader’s role in promoting collaboration. His clients have included the National Geographic Society, several military and intelligence agencies, the Archdiocese of Washington, D.C., a partnership of the Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management, Drug Enforcement Administration, National Parks Service, U.S. Departments of State, Treasury, Interior, HHS and Education, one member of Congress, one governor, two state attorneys general and over four dozen state and local government agencies. He’s also worked with several non-profit agencies in the U.S. and Israel. Before beginning his full-time practice, Russ was a Senior Faculty Member at the Federal Executive Institute. He served as the Director of Executive Programs at the University of Virginia's Center for Public Service, taught at the UVa McIntire School of Commerce, and worked in the human services field for 10 years. His volunteer commitments include scholarship programs that help low-income youth afford college. Russ Linden's bachelor's and master's degrees are from the University of Michigan. His Ph.D. is from the University of Virginia. He and his wife have two adult children. They live in Charlottesville, VA. For more, see his web site: www.russlinden.com. 2 Why this topic? Why I’m passionate about collaboration… What prompted you to take this course? 3 Collaboration – The Walls Are Crumbling: • Between agencies • In academia • Using social networks to foster information sharing and collaboration. 4 Intellipedia: Removing walls between intelligence agencies • “Intellipedia,” created in ’05, based on the Wikipedia model: a self-governing system written/edited by consumers • Like Google, it offers a way to show which postings are most used and cited • Anyone with appropriate security clearance can post entries, add information and opinions • This is peer-based evaluation: if a fact or opinion strikes a cord with enough analysts, it’s widely read • Intellipedia contributors are not anonymous; errors occur, but contributors are accountable • For more: “Open-Source Spying,” by Clive Thompson. New York Times Magazine, 12/3/06 5 Intellipedia • Some advantages: speed; ease of idea exchange; younger analysts can offer input; analysts find others with similar interests; chance to spot patterns earlier • Caveats: it’s not official IC opinion; it lacks the rigor of a formal review process; and security concerns • Many young analysts are comfortable with this system – they’re “digital natives,” idea exchange is their norm. Older ones face a cultural sea change 6 Removing walls in academia For 100 years medical education was delivered through lectures; students regurgitated facts on exams. The emphasis was on individual student learning; the tradition was “one patient, one doctor.” The model is changing. Two of the reasons: 1. About half of all medical knowledge becomes obsolete every five years, and 2. An increasing amount of medical care is handled by teams. 7 Removing walls in academia Today students learn in teams. The emerging medical model: “one patient, one doctor, and a team.” From: “Adjusting the Prescription,” in The University of Virginia Magazine, Spring, 2011. 8 Using social networks to help people collaborate “Facebook Cements No. 1 Status” -- headline in Washington Post, 12/31/’10 • Facebook was the most visited website in 2010. • Americans spent almost 23% of their online time using social networks in 2010 (more than any other Internet activity). • “We’re moving from a Google-centric Web to a people-centric Web,” noted one media analyst. 9 Collaboration – The need is apparent at the organizational level: • Lack of resources to do it ourselves • Highly complex problems that require multiple skill sets and mindsets • Create more integrated product for customers • Learn from others • Grow your network • Improved mission accomplishment 10 But collaboration can be very difficult: The National Park Service • NPS mission includes preserving resources in our nat’l parks • Its leadership emphasizes the use of partnerships • Major partnership opportunity: Maintenance • Maintenance function very large: sometimes ½ of a park’s FTE • Maintenance staff may work in same park entire career • Pay not high, but great pride in their work • Often understaffed • The issue: How help maintenance staff get comfortable working 11 with volunteer partners, to maintain parks? The National Park Service Superintendents offer many incentives to partner: • Volunteers eager to help, will do work maintenance doesn’t have time for • They’ll do low-skill work, free up maintenance for higher skill, more interesting tasks • They’ll spot unmet needs • Volunteer partners increase public support for parks • Working with volunteers gives maint. staff good experience that enhances their careers • Forming partnerships is one of the agency’s priorities 12 The National Park Service Maintenance staff know that their superintendents want them to welcome and work with the volunteer partners, but many oppose it. Why? 13 The hurdles are apparent Lack of trust among principals Fear of losing: control, autonomy, quality, resources Turf concerns, and the “self serving bias” Great amount of time and effort required Hurdles to Collaboration Narrow (“silo”) mentality Different funding streams, measures, and/or goals among the partners 14 Collaboration hurdles No perceived reward for individuals/orgs. that try to collaborate “Perverse incentives” The costs are born up front; benefits may not appear for years Different org. cultures Hurdles to Collaboration Lack of leaders’ support Concern that the exchange between partners won’t be reciprocal “Almost nothing about the bureaucratic ethos makes it hospitable to interagency collaboration.” -- Prof. Eugene Bardach 15 Another kind of hurdle 16 And another … 17 Collaboration in your agency Which collaboration hurdles need to come down in your agency? 18 Exercise Four people need to cross a bridge. It’s the dead of night, there’s no light, and there is a man-eating shark in the water, so swimming isn’t an option. They must take the bridge to get across. Their goal: Get across the bridge as quickly as possible!! Here are the constraints: • • • • The group has only one flashlight, it lights up one half of the bridge, they can’t make it across safely without it. The bridge can only handle the weight of 2 people at a time. Once someone crosses the bridge with the flashlight, it can’t be thrown back to the other side. Someone must walk it back. The four people move at different speeds. It takes each this long to cross the bridge: Mary: 1 min. Al: 2 mins. Bob: 5 mins. Carol: 10 mins. 19 Exercise Their goal: Get across the bridge as quickly as possible!! Mary: 1 minute Al: 2 minutes Bob: 5 minutes Carol: 10 minutes Question: What is the shortest time for all four to cross? 20 Collaboration requires a collaborative mindset 21 A collaborative mindset Hockey great Wayne Gretsky was asked how he performed at such a high level (he wasn’t very big, wasn’t the fastest or most aggressive player on the ice by any means). He said: “I don’t skate to where the puck is, I skate to where I think the puck will be.” Wayne Gretsky had a different mindset. 22 A collaborative mindset Collaborative leaders need to: • Think creatively: Who are some non-traditional partners to involve? What are some new ways to do this work? • Think horizontally: who else can help with this project? Who else needs to know about our work? What’s the larger picture? • Think strategically: where is the “puck” going to be? How do we position this project for success? 23 Collaboration: What? Two or more organizations (within one agency or across agencies) with a common goal, sharing: • Staff • Resources, • Decision making … and sharing ownership of the final product or service. 24 Collaboration: one of a continuum of approaches Cooperating Coordinating Collaborating Integrating Merging Less formal / intensive More formal / intensive 25 Collaboration example: JNET • Begun by Former Gov. Tom Ridge in 1996 • Goal: Enhanced pub. safety through access to agencies’ offender information and other criminal justice data • Two earlier efforts toward same goal failed due to low trust, a top-down one-size-fits-all approach, & lack of funding • Before JNET, these agencies couldn’t share electronic data; took several days to get records, photos, warrants, etc. • A cop’s killing (by a convict with 6 aliases) spurred interest • JNET’s multiple capabilities include: – – – – – – share offender information access driver license information access digital mug shots exchange photo images use secure email access searchable on-line reference libraries 26 JNET (cont) • JNET uses open Internet and Web technologies and the XML language to help agencies exchange information • Ridge provided $11M in funding, kept it a priority • Agencies control JNET through a 2-part governance structure: • Steering Team designed/developed the system; met weekly throughout the project (still meets to this day), • Executive Council (politicos) developed policy, strategic direction – met occasionally, but needed to be involved • The two-part structure helped build ownership, trust, relationships. No one agency owns it; all own it 27 JNET (cont) • St. Team had great autonomy and control: each JNET agency decides what to share, who may access it • Agencies didn’t have to let go of their legacy systems • JNET was built in “chunks;” first phase stood up in 2.5 years, fully operational in 4 years • Confidence and trust grew over time; as functionality was delivered and agency input used, concerns about control and micro management lessened • JNET is shared with fed. agencies, and all PA counties. It created a constituency of support among county leaders, who help keep its funding stable in the legislature 28 JNET – Some results • Catching those with false IDs trying to enter prisons • Apprehending suspects/known criminals on the spot (often through instant access to people’s photos and background information) • Catching absconders who avoided police for years • Using JNET’s multiple data bases and photos to make the largest seizure of cocaine in Philadelphia’s history • Quickly learning that a suspect in one case is wanted elsewhere, or is out on bail (thus, a poor risk for bail) • Using facial recognition software to identify and arrest those suspected of identity theft. For more: http://www.pajnet.state.pa.us/portal/server.pt/community/pennsylvania_justice_netwo rk/4424 29 JNET (cont) 1. What do you think were the key factors leading to JNETs success? 2. Which of those factors would be especially helpful in your agency’s culture? 30 Force Field Analysis: A tool for planning collaborative projects, anticipating hurdles FORCE FIELD ANALYSIS DRIVING FORCES 4 3 2 1 RESTRAINING FORCES -1 -2 -3 -4 GOAL: 31 Using the Force Field Analysis tool 1. Write the goal of the initiative 2. Identify the driving forces – those internal and external factors that can help achieve the goal 3. Identify the restraining forces – internal/external factors that are hurdles to achieving the goal 4. Decide the length of each line (length = its strength) 5. Identify a few restraining forces that you/your team can influence: how can you or your team reduce or neutralize those forces? 32 Using the Force Field Analysis tool Apply the tool to the JNET project: Driving forces? Restraining forces? Which restraining forces did the Governor and Steering Team address upfront? 33 1. The collaboration method The collaboration method requires these elements: • A specific shared purpose or goal that the parties can’t achieve on their own • The parties want to meet now • The appropriate people are at the table • An open, credible process • A champion(s) for the initiative • Trust: candid, open relationships 34 Why it’s sometimes hard to get the appropriate people to the table • The “appropriate people” are often needed on many task forces. • They may have higher priorities • Their bosses may have a hard time justifying the time When you invite people to join a collaborative group, realize they’re probably asking themselves two questions: 1. What’s in it for me (or, for us) to work on this? (WIIFM?), 2. What’ll it cost me (WICM?) 35 How to answer the “WIIFM” question? • The best answer for some is, “it’s the right thing to do.” Other people need more tangible benefits: • We need you to achieve the project mission • Resources are available • An executive sponsor supports the project • Emphasis on sharing credit for results • Capable, team players are involved • Early, visible successes • Playing to each person’s strengths • Important customers talk about why this matters to them 36 We also have to answer the “WICM?” question What’ll it cost me? (“WICM?”) is also on people’s minds when asked to collaborate. This is a reasonable question, and needs to be addressed. Will it cost members: • • • • • Resources? Time? Reputation (fear the project will fail)? Ability to focus on their high priorities? Control over their programs/mission? A good way to reduce perceived costs: Show your willingness to “pull the plug” it things are going poorly. 37 Another key element: An open, credible process • Joint ownership for the process • Agreed-upon ground rules (the “70% rule” is a good one) • Clear roles: who’s responsible for what • Agreed-upon game plan: phases/steps, decision-making and problem-solving methods • Metrics, and a method for holding the parties accountable • Transparency; no behind-scenes decision making • A skillful convener 38 Exercise Think of a collaborative project that you’re working on. Fill out the first 3 questions on the Collaboration Worksheet. NOTE: First discuss the Stakeholder Grid (next slide) 39 Stakeholder Power/Interest Grid High Actively Keep Involve Satisfied Them Power Keep Monitor Informed (invite in?) Low Low Interest High 40 The power, and importance, of a passionate champion 41 The tasks of the working-level champion • Articulate the project’s purpose in a way that excites others • Get appropriate people to the table, and keep them there • Help parties see common interests, and the benefits from joint effort • Generate trust • Celebrate small successes, share credit widely • Find a senior champion for the effort • Provide confidence, hope, resilience 42 The working-level champion : Self Assessment How do you see yourself? 1 2 3 4 5 Poor • Articulate the project’s purpose in a way that excites others Excellent ____ • Get appropriate people to the table, keep them there ____ • Help parties see common interests/benefits ____ • Generate trust ____ • Celebrate small successes, share credit widely ____ • Find a senior champion for the effort ____ 43 • Provide confidence, hope, resilience ____ What can we learn from the Miles Davis quintet? 44 The power of trusting relationships * Handling the 9-11 attacks at the Pentagon “You can’t hate someone whose story you know.” - Management consultant Art Cross 45 The importance of trusting relationships Causes of Alliance Failures in Business:* • Inability to manage the relationships • Poor strategy and planning • Bad financial and legal conditions * From a study of 130 companies, by Vantage Partners 52% 37% 11% 46 The Importance of Relationships “In Congress in the 70’s, most members stayed in DC on the weekends. They got to know each other and their families. Today, almost all members fly home from every weekend; we don’t know each other … If I’ve learned anything, it’s that a legislative body is built on relationships.” - Idaho Congressman Mike Simpson 47 To build open, trusting relationships On p. 60 of Leading Across Boundaries, see list of 9 approaches for building trust on collaborative teams (spelled out on pp. 61-70). 1. Which of these has worked for you? 2. Which would you like to use more effectively? 3. Are there other approaches that help you develop trust on collaborative teams? An excellent book on this topic: The Speed of Trust, by Covey. 48 Successful collaboration requires thinking politically • Identify key “veto holders”and learn their interests • Learn if some of the principals are rivals • Avoid any appearance that the lead agency(ies) are in this to grab power/resources • Widen the “arena of engagement” • Connect the initiative to the agenda of senior agency people 49 Thinking politically in collaborative projects • “Frame” partnership’s goal in a simple way, make benefits clear • Learn what key stakeholders think they have to gain, and lose • Pay attention to timing: is this the right time to move forward? • Remember one of the rules of politics: we gain power when we share it 50 Thinking politically in collaborative projects Which of these have you used? What other political “rules of the road” have you found useful? 51 Look at the handout on collaborative strategies The first page describes a process for starting a collaborative project. The rest of the handout identifies common collaboration hurdles, and some strategies to address each. The last page is a tool to use with new teams. 52 Effective collaboration strategies: exercise Think about the collaborative project that you’re focusing on. Using any items in the Collaborative Strategies handout, and your creative skills: Fill out questions 4 & 5 on your worksheet, and discuss with your partner. 53 The other key element: Collaborative Leadership One definition: “Leading as a peer, not as a superior” -- David D. Chrislip 54 55 Collaborative Leadership What collaborative leaders share: competence; comfort with risk, change, and chaos; political skills; future orientation. Most important, they: 1. Have great determination and resolve, but keep ego in check 2. Listen carefully to understand others’ perspectives 3. Look for win-win (not win-lose) possibilities 4. Use more “pull” than “push” 5. Think systemically, and connect to a larger purpose 56 1. Great determination/resolve, with ego in check “I was one of the most egotistical people you would ever meet … My ego is not a personal ego, it’s a team ego. My ego demands … the success of my team.” -- Bill Russell, star center of the Boston Celtics (which won 11 championships in 13 years with Russell), quoted in his book Russell Rules. 57 2. Listen carefully to understand others’ perspectives “I learned early that one of the most important qualities of the leader is listening without judgment…” - Phil Jackson, former pro basketball coach (who won 11 NBA championships), quoted in his book Sacred Hoops. 58 3. Look for win-win possibilities The Philadelphia Phillies, Clearwater Fl., and the new stadium 59 4. Use pull more than push In “In The Valley of Elah,” the detective uses pull when she tells the police chief, “I think you know what the right thing to do is, sir.” 60 5. Think systemically, connect to a larger purpose When Bill Leighty became the deputy at a large state agency, he found a way to transform a lifeless office into a passionate one. 61 All 5 Collaborative Leadership characteristics are demonstrated in this video about Dwight Eisenhower 62 Collaborative Leadership and your Project Think about the collaborative project that you’re working on in this course. How might effective collaborative leadership make a difference? Fill out question 6 on your worksheet. 63 Other key collaboration factors • Continuity of leadership • Each partner plays to its strengths • It’s more of a voluntary than mandatory effort • Willingness among partners to accept less than 100% - try the “70% rule.” • Resources • Results are measured, publicized, everyone gets credit • A bias for action 64 Some of our past collaborative leaders • • • • • George Washington James Madison Martin Luther King Abraham Lincoln Eleanor Roosevelt 65 Culture change in large orgs: FMS, Cisco Systems I. Collaboration at FMS 1. Which actions were most significant in creating the cultural change at FMS? 2. Which of these would be effective in your agency? 66 Efforts at major culture change in large orgs. II. Cisco Systems: From Cowboy to Collaborative Culture (pp. 257-260, Leading Across Boundaries) What impressed you about the changes at Cisco? 67 Toward a Collaborative Culture … Some emerging characteristics of collaborative organizations and cultures • Training, evaluations and promotions emphasize collaboration; rotations required for moving up • Performance management systems that require collaboration (with real accountability) • Shared (and distributed) leadership • “Requirement to share” (information) replaces “need to know” as the default mode • Creative uses of IT to engage customers as active partners in value creation – use the interactive “Web 2.0” tools • High-stakes work increasingly done in co-located units 68 Toward a Collaborative Culture … Training, evaluations and promotions emphasize collaboration; rotations are required for moving up. The Intel Community, NASA, SBA and some other agencies are moving in this direction, as a way to break down “silo” thinking and reward people for seeking a broader perspective. 69 Toward a Collaborative Culture … Shared and distributed leadership. Jazz bands (like great basketball teams) are good examples of shared leadership. They work well because * everyone knows the key and the tempo * there’s an agreement on how it should sound * they take turns sharing the lead * there is abundant trust * the players expect improvisation * the group is self-managing * the group excels when they bring out the best in each other 70 Toward a Collaborative Culture … What opportunities do you have to share leadership … • • • • When you brief your manager(s)? When you’re out of the office for a week or more? When a direct report asks your opinion? When you’re leading a staff meeting? 71 Toward a collaborative culture … Some government leaders now post frequent blogs, as a way to talk directly and informally with employees about priorities, innovations and changes. Many of these blogs invite employees to post comments, which can be anonymous. The Coast Guard leaders’ blogs are at: http://uscg.mil/comdt/blog/ The Coast Guard also developed a YouTube channel for employees, as part of its commitment to use social networking tools. 72 Toward a collaborative culture … To engage employees in improving operations, the TSA launched the “IdeaFactory” in April, 2007. It invites employees to exchange ideas on job-related issues, and offer ideas for improvement. Employees comment on, and vote on the ideas submitted. An Innovation Council reviews the top vote getters, and decides which to implement. At the end of its first year, several thousand ideas were submitted, over 39,000 comments were received on those ideas, and 20 ideas had been implemented agency wide. The Dept. of Transportation has created a similar tool, and it’s making a positive impact. 73 References “Collaborative Advantage: The Art of Alliances,” by Rosabeth Moss Kanter. Harvard Business Review, July-Aug., 1994, pp. 96-108. Collaborative Leadership: How Citizens and Civic Leaders Can Make a Difference, by Chrislip and Larson. Jossey Bass Publishers, 1994. Corps Business: The 30 Management Principles of the U.S. Marines, by David H. Freedman. HarperBusiness, 2000. Difficult Conversations, by Stone, Patton and Heen. Penguin Books, 2000. Forging Nonprofit Alliances, by Arsenault. Jossey Bass Publishers, 1998. Getting Agencies to Work Together: The Practice and Theory of Managerial Craftsmanship, by Bardach. Brookings, 1998. Good to Great: why Some Companies Make the Leap … and Others Don’t, by Jim Collins. Harper Business, 2001. Leadership Ensemble: Lessons in Collaborative Leadership From the World’s Only Conductorless Orchestra, by Harvey Seifter. Times Books, 2001. Leading Beyond the Walls: How High Performing Organizations Collaborate for Shared Success, edited by Hesselbein, Goldsmith, and Somerville. Jossey Bass Publishers, 1999. 74 References (cont.) Leading Across Boundaries: Creating Collaborative Agencies in a Networked World, by Russell Linden. Jossey- Bass, 2010. Making Collaboration Work: Lessons from Innovation in Natural Resource Management, by Wondolleck and Yaffee. Island Press, 2000. The Speed of Trust, by Stephen M. R. Covey. Free Press, 2006. The Story Factor: Inspiration, Influence, and Persuasion Through the Art of Storytelling, by Annette Simmons. Perseus Publishing, 2001. The Supreme Commander: The War Years of Dwight D. Eisenhower, by Stephen E. Ambrose. University Press of Mississippi, 1999. The World is Flat, by Thomas L. Friedman. Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2005. Virtual Teams: Reaching Across Space, Time and Organizations with Technology, by Lipnack and Stamps. John Wiley & Sons, 1997. Wikinomics: How Mass Collaboration Changes Everything, by Don Tapscott and Anthony Williams. Working Across Boundaries: Making Collaboration Work in Government and Nonprofit Organizations, by Russell Linden. Jossey-Bass, 2002. 75