Race, Racism and Health - Minority Health Project

advertisement

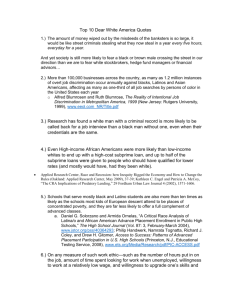

Race, Racism and Health: Patterns, Paradoxes and Needed Research David R. Williams, PhD, MPH Florence & Laura Norman Professor of Public Health Professor of African & African American Studies and of Sociology Harvard University African American Mortality • For the 15 leading causes of death in the United States in 2005, Blacks had higher death rates than whites for: 1. Heart Disease 3. Stroke 8. Flu and Pneumonia 10. Septicemia 15. Homicide 2. Cancer 6. Diabetes 9. Kidney Diseases 13. Hypertension • Blacks had equivalent rates of accidents and lower death rates than whites for: 4. Respiratory Diseases 11. Suicide 14. Parkinson’s Disease Source: NCHS 2007 7. Alzheimer’s Disease 12. Cirrhosis of the liver Hispanic Mortality • For the 15 leading causes of death in the United States in 2005, Hispanics had higher death rates than whites for: 6. Diabetes 12. Cirrhosis of the liver 13. Homicide • Hispanics had equivalent rates of hypertension kidney disease and lower death rates than whites for: 1. Heart Disease 3. Stroke 4. Respiratory Diseases 8. Flu and Pneumonia 11. Suicide Source: NCHS 2007 2. Cancer 5. Accidents 7. Alzheimer’s Disease 9. Kidney Disease 10. Septicemia 14. Parkinson’s Disease Age-Adjusted Mortality rates for 2003-2005 120 1.2 1 1 Rates 80 0.8 60 0.6 0.7 0.8 0.6 40 0.4 20 0.2 0 0 Whites Blacks Rates per 10,000 population Source: National Center for Health Statistics, 2007 American Indians Asian Pacific Islanders Hispanics Minority/White Ratio 100 1.4 1.3 There Is a Racial Gap in Health in Early Life: Minority/White Mortality Ratios, 2005 B/W ratio Minority/White Ratio 3 AI/W ratio API/W ratio 2.5 H/W ratio 2 1.5 1 0.5 0 <1 (1-4) (5-9) (10-14) (15-19) (20-24) Age There Is a Racial Gap in Health in Mid Life: Minority/White Mortality Ratios, 2005 B/W ratio Minority/White Ratio 3 AI/W ratio API/W ratio 2.5 H/I ratio 2 1.5 a 1 0.5 0 25-29 30-34 35-39 40-44 45-49 Age 50-54 55-59 60-64 There Is a Racial Gap in Health in Late Life: Minority/White Mortality Ratios, 2005 B/W ratio Minority/White Ratio 3 AI/W ratio API/W ratio 2.5 H/W ratio 2 1.5 1 0.5 0 65-69 70-74 75-79 Age 80-84 85+ Immigration and Health • Hispanics and Asian Americans tend to have equivalent or better health status than whites • Immigrants of all racial/ethnic groups tend to have better health than their native born counterparts • With length of stay in the U.S., the health advantage of immigrants declines • Latinos and Asians differ markedly in their levels of human capital upon arrival in the U.S. • Given the low SES profile of Hispanic immigrants and their ongoing difficulties with educational and occupational opportunities, the health of Latinos is likely to decline more rapidly than that of Asians and to be worse than the U.S. average in the future 30 12-Month Prevalence of Psychiatric Disorder, by Race and Nativity Status (%) US-born 25.6 25 Foreign-born 20 18.6 15 13.1 13.2 11.1 10 8.0 5 0 Caribbean Black Source: NCS-R, NSAL, NLASS Latino Asian Lifetime Prevalence of Psychiatric Disorder, by Race and Generational Status (%) 60 54.6 First 50 Second 43.4 Third or later 40 35.3 30.1 30 24.0 23.8 20 19.4 15.2 10 0 Caribbean Black Latino Source: Williams et al. 2007; Alegria et al 2007; Takeuchi et al. 2007 Asian 25.6 Challenges What are the relevant factors and what is the relative contribution of each to shaping the relationship between migration status/generational status and health for racial/ethnic minority populations? What interventions, if any, can reverse the downward health trajectory of immigrants with length of stay in the U.S.? Life Expectancy at Birth, 1900-2000 90 76.1 80 70 60.8 Age 60 50 40 71.7 69.1 77.6 69.1 71.9 64.1 47.6 White Black 33.0 30 20 10 0 1900 1950 1970 Year 1990 2000 Age-Adjusted Heart Disease Death Rates for Blacks and Whites, 1950-2004 Death Rates per 100,000 Population 750 White Black 600 450 300 150 0 1950 1960 1970 1980 YEAR 1990 2000 2004 Age-Adjusted Cancer Death Rates for Blacks and Whites, 1950-2004 Death Rates per 100,000 Population 300 White Black 250 200 150 100 50 0 1950 1960 1970 1980 YEAR 1990 2000 2004 Age-Adjusted Stroke Death Rates for Blacks and Whites, 1950-2004 Death Rates per 100,000 Population 250 White Black 200 150 100 50 0 1950 1960 1970 1980 YEAR 1990 2000 2004 Diabetes Death Rates 1955-1998 5.0 White Am Ind Am Ind/W Ratio 50.0 4.5 52.8 46.4 4.0 3.5 40.0 3.0 30.0 2.5 20.0 2.0 24.4 24.3 1.5 17.0 10.0 12.6 1.0 10.4 11.7 11.9 0.5 8.6 0.0 0.0 1955 1975 1985 Year Source: Indian Health Service; Trends in Indian Health 2000-2001 1995 1996-98 Am Ind/W Ratio Deaths per 100,000 Population 60.0 Heart Disease Death Rates Mississippi 1996-2000 White Women, Ages 35+ CDC, Heart Disease and Stroke maps Heart Disease Death Rates Mississippi 19962000 Black Women, Ages 35+ CDC, Heart Disease and Stroke maps Heart Disease Death Rates Mississippi 1996-2000 Women WHITE CDC, Heart Disease and Stroke maps BLACK Race and the Burden of Breast Cancer Compared to white women, black women are less likely to get breast cancer, BUT they are more likely to: -- get breast cancer when young -- be diagnosed at an advanced stage -- have aggressive forms of breast cancer that are resistant to treatment -- have triple negative tumors: grow quickly, recur more often, kill more frequently (Hispanic women also) -- die from breast cancer Chlebowski et al. 2005, JNCI; CA Study Race and Major Depression Blacks have lower current and lifetime rates of major depression than Whites, BUT depressed Blacks are more likely than their White counterparts to: -- be chronically or persistently depressed -- have higher levels of impairment -- have more severe symptoms -- not receive treatment Williams et al. 2007; Archives of Gen. Psychiatry Mortality Rate Neonatal Mortality Rates (1st Births), U.S. 16 14 12 10 8 6 4 2 0 White Black Mexican Puerto Rican 15-19yrs. 20-29yrs. 30-34yrs. Maternal Age Geronimus & Bound, 1991; National Linked Birth/Death Files, 1983 Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Health: More than just Socioeconomic Status Hazard Ratio Black-White Mortality Hazard Ratios Unadjusted SES adjusted 3 2.5 2 1.5 1 0.5 0 18-25 25-44 45-64 65-74 Age Franks et al., 2006; 1990-1992 NHIS linked to NDI through 1995 >75 Race and Prostate Cancer Health Professionals Study • 51,529 U.S. male health professionals, aged 40-75, followed from 1986 to 2002: • Compared to whites, blacks had elevated multivariate risk of - incident cancer 1.49 (1.13-1.96) - high grade cancer 1.75 (1.11-2.77) Non-significant risk for - fatal cancer 2.04 (0.90-4.62) Giovannucci et al., 2007 Int. J. Cancer Meharry vs Johns Hopkins A 1958 – 65, all Black, cohort of Meharry Medical College MDs was compared with a 1957- 64, all White, cohort of Johns Hopkins MDs. 23-25 years later, the Black MDs were more likely to have: higher risk of CVD (RR=1.65) earlier onset of disease incidence rates of diabetes & hypertension that were twice as high higher incidence of coronary artery disease (1.4 times) higher case fatality (52% vs 9%) Thomas et al., 1997 J. Health Care for Poor and Underserved Percent of persons with Fair or Poor Health by Race, 1995 Race/Ethnicity Percent Racial Differences B-W H-W B-H White 9.1 8.2 Black 17.3 Hispanic 15.1 6.0 Poor=Below poverty; Near poor+<2x poverty; Middle Income = >2x poverty but <$50,000+ Source: Parmuk et al. 1998 2.2 Percent of Women with Fair or Poor Health by Race and Income, 1995 Household Income White Black Hispanic Poor 30.2 38.2 30.4 Near Poor 17.9 26.1 24.3 Middle Income 9.2 14.6 13.5 High Income 5.8 9.2 7.0 SES Difference 24.4 29.0 23.4 Poor=below poverty; Near Poor=<2x poverty; Middle Income=>2x poverty but <$50,000; High Income=$50,000+ Source: Pamuk et al. 1998 20 18 16 14 12 10 8 6 4 2 0 3 2.5 2 1.5 1 0.5 0 <High High School Some School College Education College grad. + B/W Ratio Deaths per 1,000 population Infant Death Rates by Mother’s Education, 1995 White Black B/W Ratio Infant Mortality by Mother’s Education, 1995 20 NH White 18 Hispanic API AmI/AN 17.3 16 Infant Mortality Black 14 14.8 12 12.7 12.3 11.4 10 9.9 8 7.9 6 6 5.7 4 6.5 5.9 5.5 5.1 5.4 5.1 5.7 4.2 4.4 4 2 0 <12 12 13-15 Years of Education 16+ Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Health: More than simplistic genetic hypotheses What is Race? “Pure races in the sense of genetically homogenous populations do not exist in the human species today, nor is there any evidence that they have ever existed in the past… Biological differences between human beings reflect both hereditary factors and the influence of natural and social environments. In most cases, these differences are due to the interaction of both.” American Association of Physical Anthropology, 1996 Hypertension, 7 West African Origin Groups (%) 33 35 30 25 20 15 25 24 26 19 14 16 10 5 0 ia al an r r b e u r g R U n Ni n o o o er ero m m a C Ca ca i a Jam St Source: International Collaborative Study of Hypertension in Blacks, 1995 ia c u .L os d a b Bar is o n i Ill Prevalence of Diabetes, 6 West African Origin Groups age-adjusted prevalence 12 10.8 10.6 10 8.2 8.1 8 6.2 6 4 2 2 .S . U .K . U Ba rb ad os uc ia St .L ai ca Ja m N ig er ia 0 Source: Cooper et al., 1997; International Collaboration Study of Hypertension in Blacks Research Opportunity As research on the human genome moves forward, there will be increasing need for comprehensive, detailed, and rigorous characterization of the risk factors/resources in the psychological, social, and physical environment that may interact with biological predispositions to affect health risks. Why Race Still Matters 1. All indicators of SES are non-equivalent across race. Compared to whites, blacks receive less income at the same levels of education, have less wealth at the equivalent income levels, and have less purchasing power (at a given level of income) because of higher costs of goods and services. 2. Health is affected not only by current SES but by exposure to social and economic adversity over the life course. 3. Personal experiences of discrimination and institutional racism are added pathogenic factors that can affect the health of minority group members in multiple ways. Wealth of Whites and of Minorities per $1 of Whites, 2000 White B/W Ratio Hisp/W Ratio Total $ 79,400 9¢ 12¢ Poorest 20% $ 24,000 1¢ 2¢ 2nd Quintile $ 48,500 11¢ 12¢ 3rd Quintile $ 59,500 19¢ 19¢ 4th Quintile $ 92,842 35¢ 39¢ Richest 20% $ 208,023 31¢ 35¢ Household Income Source: Orzechowski & Sepielli 2003, U.S. Census Race and Economic Hardship 1995 African Americans were more likely than whites to experience the following hardships 1: 1. Unable to meet essential expenses 2. Unable to pay full rent on mortgage 3. Unable to pay full utility bill 4. Had utilities shut off 5. Had telephone shut off 6. Evicted from apartment 1 After adjustment for income, education, employment status, transfer payments, home ownership, gender, marital status, children, disability, health insurance and residential mobility. Bauman 1998; SIPP Early Life • Brain circuits in fetal and early childhood periods are affected by exposure to stress • Toxic stress during this period, such as poverty, abuse, or parental depression, can adversely affect brain architecture and lead to elevated levels of cortisol and adrenaline • When stress hormones are activated too often and for too long, they can damage the hippocampus • This can lead to impairments in learning, memory and the ability to regulate stress responses National Scientific Council on the Developing Child Child and Adult SES and Hypertension Pitt County, NC Men 8 7 Odds Ratios 6 5 Low/Low Low/High High/Low High/High 4 3 2 1 0 Age Adjusted James et al. 2006; AJPH Multivariate Adjusted Racism and Health: Mechanisms • Institutional discrimination (segregation) can restrict SES attainment and group differences in SES and health. • Segregation can create pathogenic residential conditions. • Discrimination can lead to reduced access to desirable goods and services. • Internalized racism (acceptance of society’s negative characterization) can adversely affect health. • Racism can create conditions that increase exposure to traditional stressors (e.g. unemployment). • Experiences of discrimination may be a neglected psychosocial stressor. Residential Segregation is an example of Institutional Discrimination that has pervasive adverse effects on health Racial Segregation Is … 1. Myrdal (1944): …"basic" to understanding racial inequality in America. 2. Kenneth Clark (1965): …key to understanding racial inequality. 3. Kerner Commission (1968): …the "linchpin" of U.S. race relations and the source of the large and growing racial inequality in SES. 4. John Cell (1982): …"one of the most successful political ideologies" of the last century and "the dominant system of racial regulation and control" in the U.S. 5. Massey and Denton (1993): …"the key structural factor for the perpetuation of Black poverty in the U.S." and the "missing link" in efforts to understand urban poverty. How Segregation Can Affect Health 1. Segregation determines SES by affecting quality of education and employment opportunities. 2. Segregation can create pathogenic neighborhood and housing conditions. 3. Conditions linked to segregation can constrain the practice of health behaviors and encourage unhealthy ones. 4. Segregation can adversely affect access to medical care and to high-quality care. Source: Williams & Collins , 2001 Segregation and Employment • Exodus of low-skilled, high-pay jobs from segregated areas: "spatial mismatch" and "skills mismatch" • Facilitates individual discrimination based on race and residence • Facilitates institutional discrimination based on race and residence Race and Job Loss Economic Downturn of 1990-1991 Racial Group Net Gain or Loss BLACKS 59,479 LOSS WHITES 71,144 GAIN ASIANS 55,104 GAIN HISPANICS 60,040 GAIN Source : Wall Street Journal analysis of EEOC reports of 35,242 companies Race and Job Loss Percent Black Company Work Force Losses Reason Sears 16 54 Closed distribution centers in inner-cities; relocated to suburbs Pet 14 35 Two Philadelphia plants shutdown Coca-Cola 18 42 Reduced blue-collar workforce American Cyanamid 11 25 Sold two facilities in the South Safeway 9 16 Reduced part-time work; more suburban stores Source: Sharpe, 1993: Wall Street Journal Residential Segregation and SES A study of the effects of segregation on young African American adults found that the elimination of segregation would erase black-white differences in Earnings High School Graduation Rate Unemployment And reduce racial differences in single motherhood by two-thirds Cutler, Glaeser & Vigdor, 1997 Segregation and Neighborhood Quality Municipal services (transportation, police, fire, garbage) Purchasing power of income (poorer quality, higher prices). Access to Medical Care (primary care, hospitals, pharmacies) Personal and property crime Environmental toxins Abandoned buildings, commercial and industrial facilities Segregation and Housing Quality Crowding Sub-standard housing Noise levels Environmental hazards (lead, pollutants, allergens) Ability to regulate temperature Segregation and Health Behaviors Recreational facilities (playgrounds, swimming pools) Marketing and outlets for tobacco, alcohol, fast foods Exposure to stress (violence, financial stress, family separation, chronic illness, death, and family turmoil) Segregation and Medical Care -I • Pharmacies in segregated neighborhoods are less likely to have adequate medication supplies (Morrison et al. 2000) • Hospitals in black neighborhoods are more likely to close (Buchmueller et al 2004; McLafferty, 1982; Whiteis, 1992). • MDs are less likely to participate in Medicaid in racially segregated areas. Poverty concentration is unrelated to MD Medicaid participation (Greene et al. 2006) Segregation and Medical Care -II • Blacks are more likely than whites to reside in areas (segregated) where the quality of care is low (Baicker, et al 2004). • African Americans receive most of their care from a small group of physicians who are less likely than other doctors to be board certified and are less able to provide high quality care and referral to specialty care (Bach, et al. 2004). Racial Differences in Residential Environment • In the 171 largest cities in the U.S., there is not even one city where whites live in ecological equality to blacks in terms of poverty rates or rates of single-parent households. • “The worst urban context in which whites reside is considerably better than the average context of black communities.” p.41 Source: Sampson & Wilson 1995 Segregation: Distinctive for Blacks • Blacks are more segregated than any other group • Segregation varies by income for Latinos & Asians, but high at all levels of income for blacks. • Wealthiest blacks ( > $50K) are more segregated than the poorest Latinos & Asians ( < $15,000). • Middle class blacks live in poorer areas than whites of similar SES and poor whites live in better areas than poor blacks. • Blacks show a higher preference for residing in integrated areas than any other group. Source: Massey 2004 100 90 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 90 82 81 80 Source: Massey 2004; Iceland et al. 2002; Glaeser & Vigitor 2001 80 77 C le . U .S ve la nd k N ew ar go C hi ca or k N ew Y ke e M ilw au it D et ro A fr th So u 85 66 ica Segregation Index American Apartheid: South Africa (de jure) in 1991 & U.S. (de facto) in 2000 Percentage Proportion of Black & Latino Children in Poorer Neighborhoods Than Worst Off White Children 100 90 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 Black Latino 86% 76% 69% 74% 57% 44% All Metro Areas 5 Metro Areas 5 Metro Areas High Segr. Low Segr. Neighborhood Acevedo-Garcia et al., 2008 Research Implications: Distinctive Patterns? • What effects do these distinctive residential environments have on normal physiological processes? • How are normal adaptive and regulatory systems affected by the harsh residential environment of blacks? • Due to biological adaptations to their residential environments, should we not expect to find some biological profiles that are different and some distinctive patterns of interactions (between biological and psychosocial factors) for African Americans? Internalized Racism: One response of stigmatized populations is to accept as true the larger societal beliefs about their inferiority Internalized Racism & Health: Understudied • The experimental manipulation of a stigma of inferiority (stereotype threat) leads to increases in blood pressure among blacks • Internalized racism has been positively associated with psychological distress and substance abuse in several studies of African Americans • Internalized racism has been positively associated with the risk of overweight and abdominal obesity in studies of Black women in the Caribbean and the U.S. Blascovich et al. 2001; Taylor & Jackson, 1990; Taylor et al. 1991; Tull et al. 1999; Chambers et al. 2004 Perceived Discrimination: Experiences of discrimination may be a neglected psychosocial stressor Race, Criminal Record, and Jobs • Pairs of young, well-groomed, well-spoken college men with identical resumes apply for 350 advertised entry-level jobs in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Two teams were black and two were white. In each team, one said that he had served an 18-month prison sentence for cocaine possession. • The study found that it was easier for a white male with a felony conviction to get a job than a black male whose record was clean. Devah Pager, 2003; Am J Sociology Percent of Job Applicants Receiving a Callback Criminal Record White Black No 34% 14% Yes 17% 5% Devah Pager, 2003; Am J Sociology “..Discrimination is a hellhound that gnaws at Negroes in every waking moment of their lives declaring that the lie of their inferiority is accepted as the truth in the society dominating them.” Martin Luther King, Jr. [1967] Paradies’ Review • Identified 138 empirical studies • 65% (n=89) published between 2000-2004 • 86% in U.S., but 20 studies from Europe, Canada, Australia/New Zealand and the Caribbean • After adjustment for confounders, discrimination tends to be associated with poor health • Similar to the literature on stress, consistent inverse association more often found for measures of mental health than physical health Paradies, 2006: International Journal of Epidemiology Recent Review • 95 studies in MEDLINE between 2005 and 2007 • Broader range of outcomes (e.g. uterine myomas, hemoglobin A1c, CAC, less stage 4 sleep & breast cancer incidence) • Attention to the effects of bias on health care seeking and adherence behaviors • Some longitudinal data • Focus on the severity and course of disease • Growth in international studies (e.g. national studies in New Zealand, Sweden, and South Africa; studies from Australia, Canada, Denmark, the Netherlands, Norway, and the U.K.) Williams & Mohammed, under review Discrimination and Disparities in Health Perceptions of discrimination have been shown to account for some of the racial differences in: -- self-reported physical health in the U.S. (Williams, et al., 1997; Ren, et al., 1999) and New Zealand (Harris et al. 2006) -- birth outcomes (Mustillo et al. 2004). Arab American Birth Outcomes • Well-documented increase in discrimination and harassment of Arab Americans after 9/11/2001 • Arab American women in California had an increased risk of low birthweight and preterm birth in the 6 months after Sept. 11 compared to pre-Sept. 11 • Other women in California had no change in birth outcome risk, pre-and post-September 11 Lauderdale, 2006 Every Day Discrimination In your day-to-day life how often have any of the following things happened to you? • You are treated with less courtesy than other people. • You are treated with less respect than other people. • You receive poorer service than other people at restaurants or stores. • People act as if they think you are not smart. • People act as if they are afraid of you. • People act as if they think you are dishonest. • People act as if they’re better than you are. • You are called names or insulted. • You are threatened or harassed. Everyday Discrimination and Subclinical Disease In the study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN): -- Everyday Discrimination was positively related to subclinical carotid artery disease (IMT; intimamedia thickness) for black but not white women -- chronic exposure to discrimination over 5 years was positively related to coronary artery calcification (CAC) Troxel et al. 2003; Lewis et al. 2006 Discrimination and Health Behaviors Recent studies indicate that experiences of discrimination are associated with: • Delays in seeking treatment • Lower adherence to treatment regimes • Lower rates of follow-up • Poorer perceived quality of care • Alcohol, tobacco and other drug use Van Houteven et al. 2005, Banks & Dracup, 2006; Wagner & Abbott 2007; Wamala et al. 2007 Prevalence Prevalence of Substance Use according to Racial Discrimination and Race/Ethnicity 100 90 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 Smoking Alcohol Marijuana Cocaine Crack African American African American White White None Any None Any Racial Discrimination in Years 7 and 15 Discrimination and Diabetes • A study of 848 diabetic patients found that perceived health care discrimination was associated with worse glycemic control (A1c), more diabetes symptoms, and worse physical functioning. • (Higher levels of discrimination were associated with lower ratings of the interpersonal qualities of care, e.g. “friendliness and courtesy,” “respect”). • Discrimination may adversely affect severity & course of disease by affecting patients’ levels of self-care. Source: Piette et al. 2006, Patient Ed & Counseling Discrimination and Health: New Zealand • National study of 4,108 Maori and 6,269 whites • A 5-item scale captured ethnically motivated physical or verbal attack, unfair treatment (due to ethnicity) in health care, getting a job, at work, or in housing. Maori were 10 times more likely than whites to report discrimination in 3 or more settings. • Perceived discrimination made an incremental contribution over and above SES in explaining disparities in poor self-rated health, low physical functioning, psychological distress, and self-reported cardiovascular diseases Harris et al., 2006, Lancet Discrimination and Health: South Africa • National study of 4,351 adults • All black groups 2 to 4 times more likely than whites to report chronic and acute racial discrimination • All black groups had higher levels of psychological distress than whites • Perceived discrimination made an incremental contribution over and above SES in accounting for racial disparities in psychological distress • Discrimination unrelated to poor self-rated health Williams et al., 2008, Social Science & Medicine Challenges • • • • Measuring Discrimination Thinking carefully about exposure Capturing life course exposure Conceptual clarity re discrimination and stress • Attributional Ambiguity • Dealing with Denial Subjective Nature of Discrimination 1. There can be shared response bias between the measure of discrimination and the measure of health when both rely on self-reports. 2. In mental health studies there may be confounding between reports of discrimination and health, based on selective recall as a function of current mental health. 3. How can we improve the accuracy of reports based on individual perceptions? 4. Are there simple cues to memory that can be utilized? 5. What are the key confounding factors that should also be assessed for statistical adjustment (social desirability, neuroticism, self-esteem, other?)? Social Desirability 1. Asking repeatedly about “racial discrimination” or experiences “because of your race” could produce demand characteristics in which respondents believe that it is desirable to the interviewer to report such experiences. This could lead to over-reporting of discrimination. 2. Respondents may vary in their thresholds of what constitutes discrimination and fail to report incidents that are not perceived as serious. 3. But, does “unfair treatment” really capture racial discrimination? 4. Does “unfair treatment” evoke the same experiences for whites as for blacks and other minorities? 5. Are there race of interviewer effects? Assessing Life Course Exposure 1. Research on stressful life events indicates that the falloff in reporting stressors occurs at the rate of 5% per month. 2. How can we overcome errors due to forgetting? 3. Prior research has used past month, past year, past 3 years, and lifetime time frames for reports of discrimination, but they have not used them simultaneously. How can we best capture lifetime exposure? 4. How can we measure well the timing of exposure? 5. How can we, quickly but effectively, facilitate the accurate reconstruction of past events? Historical Trauma (HT) -I • Intergenerational effects of racism, genocide, & assimilation on American Indian health • Cumulative & collective psychological wounding over the life-span and across generations • Similar to studies of other generational group traumas, such as, the Jewish Holocaust, or the internment of Japanese Americans in concentration camps • HT may contribute to unresolved grief, substance abuse, physical and mental illnesses, suicide, homicide, problematic gambling behaviors, domestic violence, child abuse & low SES in American Indians Whitbeck et al. 2004 Historical Trauma -II • Scales with good psychometric properties have been developed to assess HT • Prevalence levels of HT are high in American Indians • Recent empirical studies have found an inverse association between HT and health. • Clinical interventions to address HT have also been developed. Whitbeck et al 2004; Braveheart 2003; Attributional Ambiguity • Full knowledge is usually lacking about any specific interpersonal transaction • Ambiguity and uncertainty regarding the attribution of negative experiences could themselves lead to worry and rumination that is health damaging • How can we assess ambiguity in the perceptions of discrimination? • Importance of capturing all exposures regardless of attribution Dealing with Denial 1. Reporting discrimination can adversely affect selfesteem and feelings of control. 2. Some individuals cope with discrimination by minimizing or even denying its occurrence. 3. Some research has found that minority group members who report never having an experience of discrimination also report the highest levels of illness. 4. Is there a way to operationalize denial in the context of large epidemiological studies? Capturing Exposure • Perceived discrimination is not a magic bullet that captures all relevant race-related risk in the environment • Must be adequately assessed (comprehensively; chronic & enduring features; traumatic events) • Think of relevant exposure and lag times • Discrimination is only one type of relevant stress • Must be understood within the context of other stressors Williams et al 2003; AJPH We need a more integrated science to better elucidate how multiple dimensions of the social environment, combine, additively and interactively, to affect the onset of illness and the progression of disease processes Cumulative Biological Risk We need to identify the biological pathways by which social adversities affect health. Many biological risk factors (B.P., cholesterol, glucose, fibrinogen) are often patterned by SES. Chronic exposure to stressors can lead to physiological dysregulation across multiple physiological systems of the body. Allostatic load captures the cumulative burden of this physiological wear and tear on the human organism that increases the risk of disease. Seeman et al. 2003 Allostatic Load and Inequalities in Health • In a study of high-functioning elderly, a summary measure of allostatic load (16 biological indicators of cardiovascular risk [6], hormones [4], inflammation [4], and renal function and lung function) was inversely related to SES. • This summary measure of biological dysregulation explained one third of educational differences in morbidity. The cumulative measure of biological risk (allostatic load) explained more variance than the individual biological indicators. Seeman et al.2003 Life-Course Approaches Individuals and groups disadvantaged with exposure to a pathogenic factor, tend to be exposed to multiple risk factors. Social adversities and stressors tend to co-occur and cumulate over the life course. We need to better understand how adult health is affected by certain critical events earlier in life, as well as, by the accumulation of health risks over the life course. Evidence for Action How can we effectively intervene to reduce social inequalities in health? Reducing Inequalities -I Health Care • Improve access to care and the quality of care – Give emphasis to the prevention of illness – Provide effective treatment – Develop incentives to reduce inequalities in the quality of care Care that Addresses the Social context • Effective health care delivery must take the socioeconomic context of the patient’s life seriously • The health problems of vulnerable groups must be understood within the larger context of their lives • The delivery of health services must address the many challenges that they face • Taking the special characteristics and needs of vulnerable populations into account is crucial to the effective delivery of health care services. • This will involve consideration of extra-therapeutic change factors: the strengths of the client, the support and barriers in the client’s environment and the non-medical resources that may be mobilized to assist the client Nurse Family Partnership • Nurses make prenatal and postnatal visits to pregnant women. • Nurses enhance parents’ economic self-sufficiency by addressing vision for future, subsequent pregnancies, educational and job opportunities. • Three randomized control trials (Elmira, NY; Memphis, TN; Denver, CO) • Improved prenatal behaviors, pregnancy outcomes, maternal employment, relationships with partner. • Reduces child abuse and neglect, subsequent pregnancies, welfare and food stamp use • $17,000 return to society for each family served Olds 2002, Prevention Science Determinants of Health in the U.S. Environment 20% Behavior 50% Genetics 20% Medical Care 10% U.S. Surgeon General, 1979 Needed Behavioral Changes • Reducing Smoking • Improving Nutrition and Reducing Obesity • Increasing Exercise • Reducing Alcohol Misuse • Improving Sexual Health • Improving Mental Health Reducing Inequalities II Reducing Negative Health Behaviors? *Changing health behaviors requires more than just more health information. “Just say No” is not enough. *Interventions narrowly focused on health behaviors are unlikely to be effective. *The experience of the last 100 years suggests that interventions on intermediary risk factors will have limited success in reducing social inequalities in health as long as the more fundamental social inequalities themselves remain intact. House & Williams 2000; Lantz et al. 1998; Lantz et al. 2000 Changes in Smoking Over Time -I Successful interventions require a coordinated and comprehensive approach: • The active involvement of professionals and volunteers from many organizations (government, health professional organizations, community agencies and businesses) • The use of multiple intervention channels (media, workplaces, schools, churches, medical and health societies) Warner 2000 Changes in Smoking Over Time -2 The use of multiple interventions – • Efforts to inform the public about the dangers of cigarette smoking (smoking cessation programs, warning labels on cigarette packs) • Economic inducements to avoid tobacco use (excise taxes, differential life insurance rates) • Laws and regulations restricting tobacco use (clean indoor air laws, restricting smoking in public places and restricting sales to minors) Even with all of these initiatives, success has been only partial Warner 2000 Moving Upstream Effective Policies to reduce inequalities in health must address fundamental non-medical determinants. Centrality of the Social Environment An individual’s chances of getting sick are largely unrelated to the receipt of medical care Where we live, learn, work, play and worship determine our opportunities and chances for being healthy Social Policies can make it easier or harder to make healthy choices Making Healthy Choices Easier Factors that facilitate opportunities for health: • Facilities and Resources in Local Neighborhoods • Socioeconomic Resources • A Sense of Security and Hope • Exposure to Physical, Chemical, & Psychosocial Stressors • Psychological, Social & Material Resources to Cope with Stress Redefining Health Policy Health Policies include policies in all sectors of society that affect opportunities to choose health, including, for example, • Housing Policy • Employment Policies • Community Development Policies • Income Support Policies • Transportation Policies • Environmental Policies Guiding Principles 1. Health Policy must be re-defined to include policies in all sectors of society that have health consequences. 2. Policies which improve average health may have no impact on social inequalities in health. 3. We need policies that improve health overall and targeted interventions to address social inequalities. 4. Major gains are possible through strategies that tackle health problems that occur most frequently. 5. Families with children should be a priority. Reducing Inequalities III Address Underlying Determinants of Health • Improve conditions of work, re-design workplaces to reduce injuries and job stress • Enrich the quality of neighborhood environments and increase economic development in poor areas • Improve housing quality and the safety of neighborhood environments Improving Residential Circumstances Policies to reduce racial disparities in SES and health should address the concentration of economic disadvantage and the lack of an infrastructure that promotes opportunity that cooccurs with segregation. That is, eliminating the negative effects of segregation on SES and health is likely to require a major infusion of economic capital to improve the social, physical, and economic infrastructure of disadvantaged communities. Source: Williams and Collins 2004 Neighborhood Renewal and Health - I • A 10-year follow-up study of residents in 5 neighborhood types in Norway found that changes in neighborhood quality were associated with improved health. • The neighborhood improvements: a new public school, playground extensions, a new shopping center with restaurants and a cinema, a subway line extension into the neighborhood, a new sports arena & park, and organized sports activities for adolescents. • Residents of the area that had experienced these dramatic improvements in its social environment reported improved mental health 10 years later • This effect was not explained by selective migration Dalgard and Tambs 1997 Neighborhood Renewal and Health - II • Neighborhood improvement in a poorly functioning area in England was linked to improved health and social interaction. • Improvements: housing was refurbished (made safe & sheltered from strangers), traffic regulations improved, improved lighting & strengthening of windows, enclosed gardens for apartments, closed alleyways, and landscaping. Residents involved in planning process. • One year later: – Levels of optimism, belief in the future, identification with their neighborhood, trust in other neighbors, and contact between the neighbors had all increased. – Symptoms of anxiety and depression had declined. Neighborhood Change and Health • The Moving to Opportunity Program randomized families with children in high poverty neighborhoods to move to less poor neighborhoods. • It found, three years later, that there were improvements in the mental health of both parents and sons who moved to the low-poverty neighborhoods. Leventhal and Brooks-Gunn, 2003 Reducing Inequalities III Address Underlying Determinants of Health • Improve living standards for poor persons and households • Increase access to employment opportunities • Increase education and training that provide basic skills for the unskilled and better job ladders for the least skilled • Invest in improved educational quality in the early years and reduce educational failure Increased Income and Health • A study conducted in the early 1970s found that mothers in the experimental income group who received expanded income support had infants with higher birth weight than that of mothers in the control group. • Neither group experienced any experimental manipulation of health services. • Improved nutrition, probably a result of the income manipulation, appeared to have been the key intervening factor. Kehrer and Wolin, 1979 Income Change and Health • A natural experiment assessed the impact of an income supplement on the mental health of American Indian children. • It found that increased family income (because of the opening of a casino) was associated with declining rates of deviant and aggressive behavior. Costello et al. 2003 Health Effects of Civil Rights Policy • Civil Rights policies narrowed black-white economic gap • Black women had larger gains in life expectancy during 1965 - 74 than other groups (3 times as large as those in the decade before) • Between 1968 and 1978, black males and females, aged 35-74, had larger absolute and relative declines in mortality than whites • Black women born 1967 - 69 had lower risk factor rates as adults and were less likely to have infants with low-birth weight and low APGAR scores than those born 1961- 63 • Desegregation of Southern hospitals enabled 5,000 to 7,000 additional Black babies to survive infancy between 1965 to 1975 Kaplan et al. 2008; Cooper et al. 1981; Almond & Chay, 2006; Almond et al. 2006 Policy Area Reducing Childhood Poverty Challenges and Opportunities High/Scope Perry Preschool 123 young African-American children, living in poverty and at risk of school failure. Randomly assigned to initially similar program and noprogram groups. 4 teachers with bachelors’ degrees held a daily class of 2025 three- and four-year-olds and made weekly home visits. Children participated in their own education by planning, doing, and reviewing their own activities. Results at Age 40 Those who received the program had better academic performance (more likely to graduate from high school) Program recipients did better economically (higher employment, annual income, savings & home ownership) The group who received high-quality early education had fewer arrests for violent, property and drug crimes The program was cost effective: A return to society of $17 for every dollar invested in early education _____________________________________________________________________ Schweinhart & Montie, 2005 Research Opportunities • We currently do not know whether policies that address improving socioeconomic circumstances are best implemented at the federal, state or local level and what optimal forms such policies should take. • We need to rigorously evaluate the extent to which policies in multiple sectors of society have consequences for health and health disparities. Research Opportunities: Multiple Levels • Which community-based interventions show the greatest promise? • How can we more actively support individuals, families, and communities to make choices that promote health? • Are there specific interventions targeted at the broader, social, political and economic determinants of health that would have larger health enhancing effects on disadvantaged (socioeconomic and racial/ethnic) populations than their higher status peers? • How can we best build on the strengths and capacities of disadvantaged populations? Conclusions • • • • Racial Disparities in health are created by larger inequalities in society, of which racism is one determinant. Social inequalities in health reflect the successful implementation of social policies. We need to examine how exposure to institutional and individual forms of racism relate to each other, and combine with other risks factors and resources, and cumulate over the life course, to affect health We need to identify how innate & acquired biological factors interact with conditions in the psychological, social and physical environment to affect health risks. A Call to Action “The only thing necessary for the triumph [of evil] is for good men to do nothing.” Edmund Burke, British Philosopher www.macses.ucsf.edu www.commissiononhealth.org • • Key features now available: – Commission resources: Overcoming Obstacles to Health report, charts – Leadership perspectives/Blogs – Multimedia personal stories – Commission information and activities – News releases – Commission news coverage – Relevant news articles Coming Soon – Interactive tool to demonstrate how changing a factor such as average educational attainment at the county level could affect mortality rates – Chartbook with state-level data on health shortfalls – Issue briefs