Compelling Writing for Persuasive Grants

advertisement

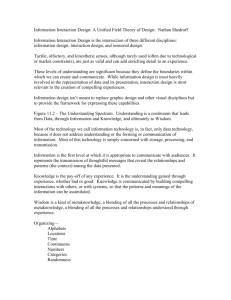

Compelling Writing for Persuasive Grants Dianne Donnelly, Ph.D. USF Associate Director of FYC, Grant Writer/Reviewer/Workshop Leader Published Scholarly Writer, Creative Writing Pedagogy ddonnelly@usf.edu The Stakes Funding Rates Reflect Competitive Climate "To maintain our edge . . . we've got to protect our rigorous peer review system and ensure that we only fund proposals that promise the biggest bang for taxpayer dollars . . . that's what's going to maintain our standards of scientific excellence for years to come." Remarks by President Barack Obama on the 150th Anniversary of the National Academy of Sciences, April 29, 2013 Why is Compelling Grant Writing So Important? • Committees review many grants • Even in times of plenty, there are more meritorious applications than can be paid • Reviewers are very busy people with limited time to make the case for your grant Positioned for Success: The Grant Process Crafting the Compelling Story Academic Writing Focus: aligns with priorities of agency/grant program Past-Oriented: completed research Future-Oriented: Research plan Audience: Likediscipline peers Audience: PO’s & both narrowly & broadly defined peers Specialized Terminology (“inside jargon”) Accessible language (broader audience) Grant Writing Focus: on scholarly pursuits of writer Allocation of Time • • • • • Approximately 1500 person hours/year 120 hours/grant * 360 hours/year for 3 grants 360/1500 = 24% dedicated to grant writing 1.9 hours/day dedicated to grant writing * Grant writing also informs your teaching, publishing, and presentation efforts Perfect Practice Makes Perfect • When we learn a new skill, we’re changing the way our brain is wired on a deep level. • In order to perform any kind of task, we have to activate various portions of our brain through practice. • Our practice helps the brain optimize for this set of coordinated activities, through a process called myelination. Perfect Practice Makes Perfect • The QUANTITY of grant writing practice is important to improving your skill but so is the QUALITY of the practice—do it often and do it effectively – perfect grant writing practice makes perfect. • Practicing skills over time causes specific neural pathways to work better. Persuasive Grant Writing Knowing Your Audience • Panelists (experts) vs. ad hoc • Interdisciplinary vs. multidisciplinary • Fair vs. prejudicial/biased Thinking Like a Reviewer • Readability is the key • Assume the audience is well-educated, but don’t assume topical knowledge • Aim the application at both the expert and the generalist – a wider breadth of audience • Write in a single voice, so the proposal is a coherent, well-integrated story • Make sure terms are well defined when you use them Knowing What Reviewers Want • WHAT are you proposing to do? • WHY is this important? • Can YOU do it? NIH Review Criteria • Overall Impact: “sustained powerful influence on the research field” • Score Review Criteria: • Significance: “how will scientific knowledge, technical capability, and/or clinical practice be improved?” • Investigator: qualifications, experience, credibility • Innovation: “novel theoretical concepts, approaches or methodologies, instrumentation, or interventions?” • Approach: “overall strategy, methodology, and analyses well-reasoned and appropriate to accomplish the specific aims of the project” • Environment: facilities, equipment & institutional support NIH Peer Review Revealed What Makes a Grant Compelling? • It tells a persuasive story • Clear, concise, confident, cohesive • Evidence-based • Follows guidelines • Guides the reader • Objectives are measurable • Investigator is credible • Timelines are reasonable • Visuals propel the story forward • Considers its audience Craft a Compelling Story • Start with an appealing, magnetizing title that stays in the mind of the reader • Begin with the pitch: Sell your idea! • Get and keep the attention of reviewers at the onset • Identify the importance – stress the need • Don’t bury important information • State your solution • Describe the concept • Establish credibility • Describe your project’s purpose • Create a Vision • Show how your work will advance the field Goals and Objectives • Formulate specific, measurable objectives • Goal: general statement of the project’s overall purpose(s) • “Our aim with this innovative curriculum is to improve the supply of graduates with National Registry certification.” • Objective: A specific, measurable outcome or milepost • “At least 90 per cent of course graduates will pass the National Registry Examination” Crafting the Compelling Story • Compel reviewers to read your proposal more carefully. • Create conflict – what is and what is not or what is and what should be, or could be • Balance between clarity and depth Delivery, Design, Documentation • Delivery (following the guidelines, guiding your reader, presenting confidence, and providing concision, cohesion, clarity) • Design (conveying visual messages) • Documentation (delivering facts & evidence) Delivery – Following Guidelines • Organize to meet expectations of guidelines and review criteria • In fact, use headings with exact wording from grant guidelines Delivery: Guiding the Reader • Use topic sentences that both introduce and summarize the info in a paragraph • Bold section headers and subheaders and critical components to guide your readers. • Propel your message forward with your visuals and captions. Delivery: Concision • Incorporate Direct, Concise Language • “The PI of this grant application has engaged in pilot work that tracked students throughout the chemistry degree path based on participation in a PLTL first semester general chemistry course.” • “In a previous pilot study, the PI of this proposal tracked those students across their chemistry degree path who had completed a first semester general chemistry course that used a PLTL approach.” Delivery: Concision • Incorporate Direct, Concise Language • “However, GBS offers an order of magnitude more fragments to characterize the genome (e.g. tens to hundreds of thousands).” • “However, instead of hundreds of fragments resolved from AFLP, GBS typically provides 20,000-50,000 fragments to characterize the genome (Narum et al. 2013).” • Consider Brevity (the fewer words it takes to convey the information, the better) Delivery: Cohesion • Simplify sentences – break up long sentences, but keep an interesting rhythm to avoid choppy, staccato sentences • Vary future tense (“We will”). For example, We plan to ….The project aims to…I propose to… • Construct parallel structure – create expressions of similar content and construction. For example, (written as an aim), “Immobilization of enzymes into mesoMOFs and evaluate the performances of enzymes… • Immobilization of enzymes into mesoMofs and evaluation of their performances in enzymatic catalysis. Delivery: Confidence • Use active verbs • For example, "It has been reported by the NIH that the India proposal was found to be complex," becomes, in the active voice: "The NIH found the India proposal complex.“ • Sound confident, but not arrogant • Global warming is an on-going problem; the world needs to learn more about how global warming works and what the consequences are. Then we can combat global warming. • The project proposes a series of experiments and models that will expose how global warming works and what consequences exist. This research will lead to better ways to combat global warming. Delivery: Confidence • Use power packed words/phrases • provide, prepare, direct, significant, empowering, catalyst • Vary your sentence structure and word choices • complex, compound, simple • Craft concrete “visual” language • Limit adjectives and adverbs • Watch clichéd words • state of the art, in the final analysis, think outside the box, in the current climate, etc. Delivery: Clarity • Subject Verb Disagreement • In addition, the rigor associated with STEM disciplines and the cost to benefit ratio associated with pursuing studies in the disciplines plays a significant role in decisions to persist. • In addition, the rigor associated with STEM disciplines and the cost-to-benefit ratio associated with pursuing studies in the disciplines play a significant role in decisions to persist. • In addition, the rigor associated with STEM disciplines along with (or as well as) the cost-to-benefit ratio associated with pursuing studies in the disciplines plays a significant role in decisions to persist. • Make pronoun usage clear rather than vague or ambiguous Your Turn: Change Passive to Active • It has been demonstrated by research that…. • The SAP Program is being implemented by our department this year. • Following administration of the third dosage, measurements will be taken. Informational Design • Figures, Images, Arrows, & Tables help show the flow of ideas/aims, highlight important points, & convey your thinking and approach • Make it easier for reviewers to understand your ideas and appreciate the immediate visual impact • Connect the graphic to the aims of the proposal • Convey the amount of time and effort that was put into the grant proposal • Establish the “identity of the project” by broadening the medium that the project is being viewed in Informational Design • Note the following in visuals: • What’s in the figure? • Explanation of any artifacts in the figure • The concept/problem the figure addresses (why is the figure included?) • Label all axes in tables and graphs – show if a low or high number is good and why • Be careful of boxes. If possible, leave the sides open so the reader has visual entry. Informational Design Informational Design: Concept Figures Figure 2. Framework of the proposed integrative SWFBIS research and education program. The SWFBIS study seeks new insights on the understanding of BI sustainability through interdisciplinary research on the coupled human-natural BI systems. The SWFBIS program integrates 4 research aspects, including physical-geologic processes, ecosystem functions and services, social-political dynamics, and engineeringinfrastructure vulnerability. Documentation LOIs and Letter Proposals • Speak to WHY you, WHY this grant • Write succinctly – brevity is key • From 15 pages to 1, 3 or 5 pages • Not an abstract of a full grant • Avoid technical jargon and acronyms • Bold statement of positive language • Know and define your purpose Letters of Inquiry & Letter Proposals • Triage – selective LOIs • Gauge response – all LOIs move forward • Know the art of the elevator speech • • • • Form a clear introduction Tell a story Hook your reader Conclude with a call to action Typical LP/LOI Structure • Project Title – descriptive, impactful, succinct • Project Summary (Opening paragraph) • Project Description – systematic, foundationspeak, assertive • Summary budget – Clear, reasonable, competitive Project Summary • Third-person description of objectives, methods, significance. • 1 page limit • Be sure to include and label a section on Intellectual Merit and a section on Broader Impact. Project Description • Page limit awareness • A broader theoretical framework that works down to one or a few focal questions • A well-specified, scientifically sound research plan to test answers to the focal questions • Clear and believable statements regarding prospective intellectual merit and broader impacts • A sound management plan and descriptions of who will do what work ACTIVITY: 10-15 mins. • Consider your current project or research interest • Pitch your idea. Why you and not another investigator? Persuade me to fund you idea. What would result if you were funded? • State your purpose and case for need up front; build a compelling argument • “This proposal aims to … • Write your objective section. • Share with your colleague(s) Intellectual Merit • Why is your research important for the advancement of your field? • Questions • • • • What is already known? What is new? What will your research add? What will this do to enhance or enable research in your field or the field of others? Use Short Summary Statements to Help Reviewer • This work is important because … • The investigators are well qualified on the basis of their background and experience… • The most creative aspect of the proposal work is… • There are potentially transformative aspects of the proposed work, which if successful, could… ACTIVITY: 10 - 15 mins. • Develop your Intellectual Merit section • How is your work going to advance knowledge in your field? • Speak to your qualification as a PI • Are you addressing gaps in the knowledge base? Do you have evidence of that gap? • Share with your colleague(s) This work is important because… Broader Impact ACTIVITY: 10-15 mins. • Review the NSF Broader Impact Review Criterion in your handout. • In pairs, try to develop a broader impact(s) that thematically extends beyond your particular research study. Thank You! Resources • Stay current with the research news and what’s trending at the federal funding agencies… one way is through GUIRR, the Government University Industry Research Roundtable • The Foundation Center posts the text of its Proposal Writing Short Course. • The University of Michigan hosts a useful Proposal Writer’s Guide. • The Human Frontiers Science Program posts its monograph on the Art of Grantsmanship. • This ACLS article outlines the essentials of proposal writing for fellowship competitions. • Michigan State University has a listing with links to over 100 proposal guides, including ones that focus on specific disciplines or on applications to specific agencies and organizations. Resources Advanced Manufacturing Cybersecurity Big Data Innovation International Research Outsourcing Research & Development Education Energy & Environment IP/Patents Jobs/Workforce Resources