View Presentation

advertisement

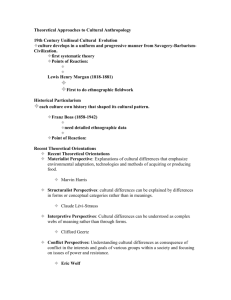

Chapter 12 Helping Behavior Definitions Altruism means helping someone when there is no expectation of a reward (except for feeling that one has done a good deed) Prosocial Behavior Altruism Prosocial Behavior includes any act that helps others, regardless of motive. Definitions Types of Helping (McGuire, 1994) Casual help, e.g., giving directions Substantial help, e.g., lending $$ Emotional help, e.g., listening Emergency help, e.g., taking someone to E.R. Definitions In general, we tend to be more helpful to those we know and care about than to strangers Theoretical Perspectives An Evolutionary Perspective Many examples of prosocial behavior have been observed among animal species. Endangering one’s own life to help another, on the surface, seems incompatible with reproductive fitness. “Kin selection” provides an explanation. Animals help others more who are genetically related. Mothers are more helpful than fathers. However, these ideas are controversial. Theoretical Perspectives A Sociocultural Perspective Human societies have gradually evolved beliefs or social norms that benefit the welfare of the group. Norm of Social Responsibility Norm of Reciprocity Help those who depend on us Help those who help us Norm of Social Justice Maintain equitable distribution of rewards Theoretical Perspectives A Learning Perspective We learn to be helpful through reinforcement and observation. Children help and share more when they are reinforced for their helpful behavior. Children and adults exposed to helpful models are more helpful. For children, helping may depend largely on reinforcement, but as they get older, helping may be internalized as a value. Theoretical Perspectives A Decision-Making Perspective People decide whether or not to offer assistance based on a variety of perceptions and evaluations. Help is offered only if a person answers “yes” at each step. Theoretical Perspectives (Latané & Darley, 1970) Theoretical Perspectives Perceiving a Need Characteristics that lead us to perceive an event as an emergency: Event is sudden & unexpected. Clear threat of harm to a victim. Harm will increase unless someone intervenes Victim needs outside assistance. Effective intervention is possible. Theoretical Perspectives Taking Personal Responsibility Being given responsibility increases helping. Perceiving oneself as competent to help increases the likelihood of taking responsibility. Theoretical Perspectives Weighing the Costs and Benefits At least in some situations, people weigh the costs and benefits of helping and of not helping. However, in other cases, helping may be impulsive and determined by basic emotions and values rather than by expected profits. Theoretical Perspectives Deciding How to Help & Taking Action In emergencies, decisions are made under high stress. Well-intentioned helpers may not be able to give assistance or may mistakenly do the wrong thing. Theoretical Perspectives Attribution Theory We are more likely to be empathetic and to perceive someone as deserving help if we believe that they did not cause their problem. Who Helps? Mood and Helping People are more willing to help when they are in a good mood. Mood-maintenance Good moods increase positive thoughts “Feel good” effect is short lived. Who Helps? Mood and helping Negative moods sometimes lead to more helping. Negative-state relief model suggests that people may help as a way to make themselves feel better. Less likely to occur if a person is focused on themselves and their own needs. Who Helps? Personal Distress refers to our own emotional reactions to the plight of others. Occurs when we are preoccupied with our own feelings and leads us to focus on reducing that distress. Fosters “egoistic helping:” We’ll help only if we cannot easily escape the situation or ignore others’ suffering. Who Helps? Empathy refers to feelings of sympathy and caring for others. Occurs when we focus on the needs and the emotions of the victim. We are more likely to feel empathy for those who are similar to us and those who did not cause their own distress. Fosters altruistic helping. Who Helps? Toi & Batson (1982) All participants learned about Carol, who had broken both legs in an accident and needed assistance catching up with schoolwork. High empathy condition was told to focus on Carol’s feelings; Low empathy condition was told to be objective. 71% high empathy, 33% low empathy helped. Who Helps? There is a controversy over interpreting studies on empathy. Batson views empathy as increasing altruistic motivation Cialdini argues that helping based on empathy is not entirely altruistic because the helper’s goal is to improve his/her own mood. Who Helps? Personality Characteristics There is no single type of “helpful person.” Rather particular traits and abilities lead people to help in different specific types of situations. E.g., people who help in potentially dangerous emergencies are bigger and tend to have training in coping with emergencies. Who Helps? Gender and Helping Men are more likely to engage in helping that is heroic and chivalrous. Men are more likely to help strangers— especially if the person needing help is female, if there’s an audience, and if the situation is dangerous. Who Helps? Gender and Helping Women are more likely to engage in helping that is nurturant. Care-giving, emotional support, doing favors. Bystander Intervention Bystander effect = people are less likely to help (and take longer to help) the more people there are present Kitty Genovese murder sparked research Why does the bystander effect occur? Diffusion of responsibility Pluralistic ignorance Evaluation apprehension Bystander Intervention Environmental Conditions affect helping. People are more helpful when it’s pleasantly warm and sunny. People are more likely to help strangers in small towns & cities than in big cities. What matters is current environmental setting, not where person was raised. Explanations: anonymity of cities, fear of crime, information overload, feelings of helplessness. Bystander Intervention “Good Samaritan” study (Darley & Batson, 1973) Participants were seminary students asked to give a short sermon Some were told to hurry across campus, others to take their time 63% of those not in a hurry vs. 10% in a hurry helped a groaning stranger they passed. Time pressure particularly affected those who believe their research participation was of vital importance (Batson et al., 1978). Volunteerism Volunteer helping is planned, sustained, and time-consuming. Motives for volunteering: Expressing Values Gaining knowledge, skills, & experience Gaining social approval and new relationships Advancing career Putting aside own problems Gaining personal growth & self-esteem Self-focused reasons may promote longterm helping. Caregiving Most helping is given to friends and relations. Helping given to strangers is usually spontaneous, that given to intimates is usually planned. Women are more involved in caregiving helping than are men. Receiving Help Reactions to receiving aid are quite varied. Receiving Help Attribution Theory If being helped implies a personal deficiency rather than a difficult situation, it can be threatening to selfesteem. If being helped implies the others’ genuine caring, it can boost self-esteem. Receiving Help The Costs of Indebtedness Helping is most appreciated when it can be reciprocated so that an equitable balance is maintained in the relationship. One-way helping threatens equity and creates power imbalances. Receiving Help Reactance Theory Helping may be perceived as a threat to independence and induce reactance. According to reactance theory (Brehm, 1966), people want to maximize their personal freedom and choice. Feeling that one’s freedom is threatened leads to negative reactions. Receiving Help New Ways to Obtain Help Self-Help Groups minimize the costs of being helped because they offer opportunities for reciprocal helping and foster knowledge that others have the same problem. Computers can provide assistance anonymously and with no expectations of reciprocity and also minimize costs of being helped.