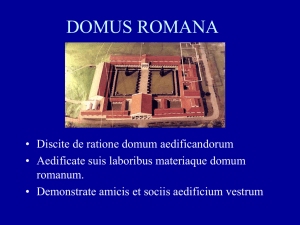

Domus Romana

advertisement

POMPEII AND HERCULANEUM DOMUS ROMANA PROBLEMS OF EVIDENCE Use of Vitruvius’ descriptions is unreliable since the purpose was to describe ideal architecture rather than reality There is no such thing as a standard house in Pompeii or Herculaneum. Hadrill identified four different groups of houses, combining various degrees of residential and commercial function Room function is highly interpretive, reflecting historical context The removal of material culture from their context makes room function almost impossible to determine. To attribute single room function is dangerous since rooms may have been multifunctional. The discovery of loom weights in the atria of 6 houses could indicate the multi functional use of this space Assumptions about dwelling/owner relationship is only conjecture Evidence for tenement/apartment housing or upper floor use is almost non existent in Pompeii due to the collapse of upper stories. Any previous analyses of housing has focused on affluent housing, because of its inherent artistic and architectural value. It misrepresents however the type of accomodation for a large proportion of the population Axis of Symmetry Andrew Wallace Hadrill Grand Amici Paterfamilias Private Public Clientale Servi Humble Houses opened directly on to the street and because they were designed to face inwards, their facades were austere with little indication of the elegance within The key feature in the design of urban houses (domus) for the Roman elite is the long axis running from the street entry to the garden. This axis ties together fauces ("jaws"), atrium, tablinum, and peristyle; it is framed by columns (often positioned, as here, to "force" the perspective and make the house look bigger than it actually is). The house falls naturally into to two basic zones, the "negotium" ("business") half focused on the atrium and tablinum, and the "otium" ("leisure") half, focused on the peristyle. Most houses included several dining rooms and cubicula, and many included small, private bathing facilities. ATRIUM After passing into the house from the street through the fauces, a visitor to a Roman house entered the atrium. As a circulation space, the atrium tended to receive less complex decoration than dining rooms or cubicula. Small figures and still lifes are far more common than mythological central panels, and the third and fourth style schemes tend to be rather simple and flat. The atrium had a sloped roof to collect rain water, which fell through the compluvium (the square opening in the roof) into the basin in the floor (the impluvium). A black/white mosaic style has been chosen for the atrium, again because this is a circulation space--visitors typically would not have enough time in this area of the house to appreciate complex mosaics and mythological cycles. The monochrome mosaic style used here is consequently less ornate in comparison to the mosaic pattern chosen for the peristyle TABLINUM Located along the axis running from the fauces through the atrium and on into the garden, the tablinum constituted a sort of office or headquarters for the dominus. Here, he received his clients during the morning salutatio, backlit by the garden and lit from above the the compluvium (shades of The Godfather). The dominus was also able to command much of the house visually from his panoptic vantage point in the tablinum, looking forward into the atrium, and back into the garden--a visual authority to match the social authority of the paterfamilias. As a more static space for reception, the tablinum often includes central paintings in its third and fourth style schemes. TRICLINIUM Dining was the defining ritual in Roman domestic life, lasting from late afternoon through late at night. Typicallly, 9-20 guests were invited, arranged in a prescribed seating order to emphasize divisions in status and relative closeness to the dominus. As static, privileged space, dining rooms received extremely elaborate decoration, with complex perspective scenes and central paintings (or, here, mosaics). Dionysus, Venus, and still lifes of food were popular, for obvious reasons. Middle class and elite Roman houses usually had at least two triclinia; it's not unusual to find four or more. Here, the triclinium maius (big dining room) would be used for larger dinner parties, which would CUBICULA The cubicula (plural for cubiculum) were used for work and study, the private reception of a small number of guests, and sleeping. It was common for these intimate rooms to be highly decorated, often with erotic scenes. They were also found in suites with triclinia (dining rooms) and baths, so that the owner and his privileged guests could move easily and "naturally" from one activity to the next. As in this instance, cubicula often had barrel vaulted ceilings. Sometimes, these worked together with mosaics on the floor to define small alcoves for beds PERISTYLE The peristyle garden was the center for "leisure" (otium) in the Roman house. Off this large circulation space were found rooms devoted to dining and the reception of the owner's social equals (amici). The peristyle recreates in miniature the public porticoes found in Roman cities (e.g. the Portico of Octavia in Rome). These public porticoes provided cool, shaded walking space beside temples and theaters, and were often used as outdoor "museums" for the display of art. The peristyle garden in the house alludes to this public, urban form of architectural patronage. The movement from the "negotium" (business) part of the house to the "otium" (leisure) part is marked by the switch from black and white to more complex, colorful floor mosaics