Policy Analysis of Open Streets Programs and Street Closures as

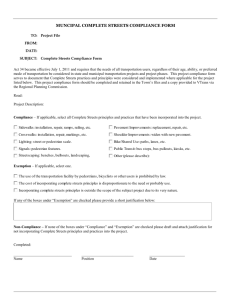

advertisement

Policy Analysis of Open Streets Programs and Street Closures as Policy Tools Johann Weber, Georgia Institute of Technology Executive Summary About the Project: Though street festivals are commonplace around the world, the recurring closure of a street space to motor vehicle traffic for the purposes of improving public health, boosting business, and fostering community is a relatively new development. These so-called “Open Streets” programs (or “Ciclovías”) are structured like recurring special events, but are undertaken by local governments and partners in order to accomplish particular policy goals and foster policy outcomes, including supporting local businesses, encouraging active lifestyles, fostering alternative transportation modes, and building stronger bonds within the community. This project seeks to better understand these programs and their impacts, particularly on local communities and businesses, by using both a localized survey and a comparative case study employing stakeholder interviews. Methods: This research includes both a quantitative and qualitative component. The Atlanta Streets Alive survey collected data on business impacts and experiences, including questions intended to capture changes in retail sales, frequency of visits, level of involvement, customer feedback, and overall perceptions. The survey goal was to capture the experience of businesses with regards to a local Open Streets program. A comparative case study was also used to illuminate contextual variables that may affect the impact of such programs. Interviews were conducted with key stakeholders (namely program organizers and sponsors) from case locations including Portland, San Antonio, Austin, Savannah, Charleston, Rome, and Macon. This case comparison informs an analysis of factors influencing program frequency, organization, size, location, and funding, as well as providing guidance and policy recommendations for both current and future programs. Finally, a comprehensive review of the associated research literature will supplement findings to form the basis of final policy recommendations. Purpose: The goal of the research is to identify the impact that Open Streets programs have on their corridors and the associated areas, how these programs are implemented and operated, and to identify what implications the programs have for the use of street closures as a recurring policy tool. The aim is to better understand what benefits and challenges exist in the programs currently, as well as what has led some programs to be expanded into a regular operation of the space or a more recurring phenomenon, and provide useful recommendations for existing and future programs. Results: Limited responses to the business survey were insufficient for statistical analysis, but sufficient for qualitative discussion. Responses were heavily mixed, with some businesses observing reduced foot traffic and revenue during the day of the program, and others experiencing increased traffic and revenue (as well as some seeing more traffic and less revenue). Likewise, while some businesses positively valued the exposure and activities, others were limited by the closure of the street or their position along the route. Though a majority of businesses were supportive of the program returning, regardless of their particular sales on that day, a few businesses were not supportive. Interestingly, none of the businesses were particularly engaged in the program, electing to conduct business as usual; this may have limited their ability to draw in program participants (future research here is needed). The case study identified some similarities and differences among the case cities. All the large cities saw large average turnouts, though some were higher than others; small cities’ programs were similar, though attendance, route size, and costs were scaled down. Semi-annual programs were the norm, with some variation based on considerations of resources, weather, and stakeholder interest. Costs per attendee were fairly similar, particularly across larger programs (smaller programs were less consistent). In every case a large private sponsor was critical, and the city government was closely involved if not in planning then in funding. In all cases nonprofit organizations played central roles in organization and implementation, and public entities supported them. Programs expressed common goals related to economic development, transportation, public health, and community development. To accomplish these goals, they used a variety of programming including group activities, special business involvement, and open space for interaction. Programs appear to be more successful at accomplishing goals when program structure and features are tailored directly to program goals, rather than allowed to develop freeform. Conclusions and Recommendations: This study of Open Streets programs identified a number of positive opportunities. Programs demonstrated the ability to increase participant physical activity, generate increase revenue and business traffic, improve community interaction and perception, and encourage alternative modes of transportation. However, programs require a great deal of planning and close interaction with stakeholders throughout the program. In addition, the quantity of resources needed to make a program successful and sustainable is nontrivial. With that said, a few specific recommendations may help to optimize Open Streets programs: Firstly, goal setting is an obvious but critical first step. Secondly, involve as many stakeholders as possible as early as possible, and in whatever ways are feasible. Thirdly, match the program features to the goals identified. By keeping in mind specific goals, route choices, street closures, and program frequency decisions can all be made to optimize desired outcomes. Finally, program evaluation is a useful step not only for validating the investment (capturing attendance, economic impacts, activity levels, and community outcomes), but also for learning and improving the program over time. Though this study is not exhaustive or without its limitations, these are confident recommendations and will serve any non-profit or public entity considering an Open Streets program well. Additional recommendations for existing programs are provided as well. The Issue Cities are increasingly facing challenges that are not easily understood or addressed. Many of these challenges are what might be considered “wicked problems” (Rittel and Webber 1973): these problems are not easily defined, have no stopping rule or exhaustible set of possible solutions, and are often intertwined with other problems in a set of feedback loops. For example, many cities have been faced with decreased investment in their central business districts as a result of increased suburbanization, made possible by inexpensive fuel and housing opportunities, plentiful transportation budgets, and externalized costs (congestion, pollution). Any attempt to spur increased development in a downtown business district, or to draw renewed interest in local businesses and industries, must combat the numerous mechanisms which support the national retailer located on the periphery of a city. These wicked problems have led to increased interest in pursuing policy tools that might combat interrelated problems with a broader approach, rather than attempting to engineer a “right” answer. Consider Table 1: Table 1. Intersection of the Issues Economic development is a priority for municipalities of all sizes; however, it is a problem that is tied closely to non-economic factors, such as community bonds and confidence and the very physical health of the populace. As such, addressing economic development and failing to address the associated factors may risk a very incomplete response, and worse, a response that is eroded over time by negative feedback mechanisms accelerated by other intersecting challenges. Open Streets programs have become increasingly common over the last half decade as municipalities, non-profits, and private partners have all realized the opportunity to use a recurring community-level program, centered on the closure of a street to motor vehicle traffic, as one piece of a more creative policy strategy. Open Streets offers the chance for community residents to interact directly with each other and their local businesses, and in doing so to become more physical active. This increased activity and engagement in turn encourage a return to businesses and a renewed interest in the community itself; by recurring this program, a municipality might provide an invaluable boost not only in direct benefits but also by turning the feedback mechanisms to their advantage. Of course, as with any policy tool there are challenges and costs involved, but the goal of using a street closure as a policy tool is worth exploring further, in the search for a creative strategy for solving a diverse suite of issues. Introduction to Ciclovía Closing streets to motor vehicle traffic is not a particularly novel activity; streets festivals and special events of all shapes and sizes have done so for as long as there have been streets to close. Yet these one-off events have tended to require street closures merely as a byproduct of the scale or location of their activities. In most of these cases the street is merely a chance location unfortunately impacted by a concert or fair. However, the last few decades have seen the street closure used in a novel way and to significant effect. These programs, commonly referred to as “Open Streets” or “Ciclovía” (Spanish for ‘bike lane’), focus on the conversion of a traditional roadway (one where automobiles are the dominant mode) into a large public venue where particular public goals can be accomplished. For example, an Open Streets program might include large areas dedicated to physical activity, such as dance classes, sports fields, or simply space to walk, run, or bike without fear of traffic. The program might include business specials, extended hours, and street seating to draw customers into businesses they hadn’t tried or on days they might not otherwise visit. It might also create large areas for visitors to mix and mingle and visit non-profit vendor tents, engage in public dialogue, or enjoy entertainment. In these different ways, the closure of the street can potentially be used as an economic development tool, drawing attention to neglected areas or building business in a prominent corridor (perhaps even drawing new tenants and investment). It can also be a tool for encouraging physical activity and combating public health issues such as obesity, cardiac illness, and diabetes. It may even build stronger communities and foster positive relationships with neighbors, neighborhoods, and the city at large. The policy impacts associated with these programs have made them increasingly appealing to municipalities of all sizes as ways to affect positive change in their communities. Unlike special events, which are tailored to draw tourism dollars into the community, Open Streets programs are focused on providing direct opportunities for activity, engagement, interaction, and development at a community level. Literature Review While open streets programs have been around in the Americas since the late 1960s, the last few years have truly seen a steep increase in their popularity and presence. Though the most iconic example of the open streets program, Bogotá’s Ciclovía, is almost 40 years old (having started in 1974), most North American cities have only recently become aware of the concept. One estimate identified ten examples of such programs in 2006; by 2011 that number had climbed to more than 70 (Streets Plan 2012). With this growth in program experimentation has come a slower but still present interest in better understanding the programs and their operation, organization, and impacts. A sizable portion of the literature on open streets-style programs has focused on Ciclovía itself, unsurprising considering its prominence and the size of the program (it currently occurs every Sunday across 70 miles of streets and can include more than 1 million people per week). Some of this work has been focused on evaluation (Montes et al 2012, Wright and Montezuma, Torres et al 2013), while others have looked at factors influencing its success (del Castillo et al 2011, Cervero et al 2009). Despite the increasing popularity of Ciclovía as a research subject, others cities have also drawn attention, including San Francisco (Zieff et al 2010), St. Louis (Hipp et al 2012), Los Angeles (Lugo 2013), and Chicago (Mason et al 2011). Policy Impacts Since open streets programs are intended to generate positive public impacts, program evaluation is a popular and valuable task for both third party researchers and program organizers. For some programs, such as Portland’s Sunday Parkways, the scale of public financial support for the program is such that a regular annual report is required and includes discussion of program implementation, operation, and evaluation (including participant surveys and interviews). Others, such as St. Louis Open Streets, have been the site of both organizer and academic evaluation. Regardless of the party undertaking the assessment, and the location of the program, the findings seem to support some general conclusions. First among these conclusions is that participants experience much higher levels of physical activity than they might otherwise (Torres et al 2013, Montes et al 2013, Zieff et al 2010, Mason et al 2011). They also express greater feelings of community solidarity (Torres et al 2013, Lugo 2013) and positive perceptions of the community (Hipp et al 2012, Mason et al 2011) as a result of the program. The benefits associated with the increased physical activity were even found to be valuable enough to offset the cost of the program by a factor of 2.3 in San Francisco and 3.2 in the case of Bogotá (Montes et al 2012). Retailers and restaurants appear to experience higher than normal sales on a regular basis (Zieff et al 2013), and demand for additional vendors in Bogotá is sufficient to boost local employment relative to non-program days (Wright and Montezuma). In St. Louis, researchers found that 73% of participants spent money at a business during the program, and 68% became newly aware of a store/restaurant (Hipp et al 2012). In addition, one study found that partnerships built during the program fostered additional community efforts afterward (Mason et al 2011). These impacts provide preliminary and general support for the value of such programs, but they also serve to provide some guidance on factors identified in each study as influential for program success. Factors Influencing Success With any large program such as Ciclovía, it’s extremely difficult to isolate particular components to which success can be attributed. However, some efforts to survey attendees have found that residential proximity to program routes is associated with higher participation (Cervero et al 2009, Sarmiento et al 2010, Mason et al 2011), which does suggest that route selection will be heavily responsible for attendance. Attendance, in turn, was found in another study to be far more responsible for the size of impact outcomes than was the size of the route (Montes et al 2012). On the planning and organization side, Bogotá organizers identified the important of having support from both smaller and large scales of government, and the participation of stakeholders in program organization and implementation (del Castillo et al 2011). Program Organization and Features Streets Plan, a partnership of various non-profits, conducted the largest cross-comparison of Open Streets programs in North America to date in early 2012 (Streets Plan 2012). In their analysis of the 70 programs they identified at that point, they found a variety of funding and operation structures. Sorting by leadership organization and funding source, they identified the following typology: Table 2. Open Streets Organization Typology Model (named after the first city, Leadership Funding Source Seattle Cleveland San Francisco Publicly funded Privately funded Privately funded chronologically, to employ this structure) Portland Publicly led Non-profit led Publicly/Non-profit led Publicly led Winnipeg Non-profit led Savannah Kentucky Public/Privately led Public/Privately led Public/Privately funded Public/Privately funded Privately funded Publicly/Privately funded This typology demonstrates the frequency of partnerships between public, private, and non-profit entities in such programs, and highlights the diversity of approaches that can be successful for program implementation. The same diversity appears when looking at program characteristics. Consider the following table constructed of ranges in program characteristics among those programs identified within the Streets Plan comparison: Table 3. Open Streets Program Characteristics Feature Minimum Host city population 12,000 Average Attendance 300 Route length .2 miles Frequency of program Annually Maximum 8,000,000 100,000 32.6 miles Weekly In addition to wide variation in program size, frequency, and attendance, there are also variations in program goals, evaluation methods, and the type of sponsoring agency (privately funded may mean a health care provider, a grocery chain, a soft drink manufacturer, or any number of other entities). Of those programs reviewed by Streets Plan, most appeared to be focused around community development and physical activity goals, with a few also aiming to generate interest in local business corridors. Additional goals identified include encouraging interaction across diverse neighborhoods, drawing attention to parks and other recreational resources, and supporting non-motorized modes of transport. Program features included more than just a range of route locations and distances. Some may opt to incorporate public parks, or connect two park spaces by the route; others are heavily residential and bridge neighborhoods that are traditionally separated by roadway infrastructure. Programs may bring in outside vendors, or choose not to in order to focus on existing businesses. Activity centers might be organized, or large spaces made available for activities to develop organically. Taken together, this paints the picture of a program that is flexible to the needs and features of its community. Given sufficient grassroots, communitylevel enthusiasm for the program (another common feature across the large majority of programs), it’s likely that the outcome of any given program will be simultaneously similar to others, and very much unique. Research Questions and Goals There is a small but meaningful quantity of literature devoted to the Open Streets program, particularly Ciclovía. Amongst the limited comparative work, the focus has been on creating meaningful typologies and identifying the range of program characteristics. This is a sizable and crucial task, as program organization and operation vary from site to site but always influence the degree of the program’s success. As such, contributing to the understanding of program organization and operation is an important research task. R1: How are Open Streets programs organized, and operated? What goals are associated with the programs? While some research has worked to classify programs according to their organizational and funding arrangements, no work before has considered the variation in program goals and how they may influence program outcomes, as well as how they may be related to program organization in order to better support desired outcomes. This leads to a second research question, focused on the assessment of impacts and how they may play a role in program development: R2: What benefits do stakeholders see from the programs? How do these benefits influence program structure, organization, and/or funding? Among the potential desired outcomes are the more oft-discussed physical activity levels and community perceptions, but there may also be economic development goals. As such, a better appraisal of how Open Streets programs impact businesses along the program route, as well as how such programs may serve economic development goals more broadly, is of great interest for this project. R3: How do Open Streets impact businesses along the route? Considering the policy goals and impacts of Open Streets programs, of particular interest is better understanding of what factors influence the frequency of program occurrence, and whether there is interest on the part of stakeholders to increase the frequency of the program, or expand the program in other ways (such as more locations or a larger route). R4(a): What factors influence the frequency of recurrence of Open Streets programs? R4(b): Is there interest on the part of stakeholders to increase the frequency of the programs? By investigating these questions, we hope to have a better grasp on what differentiates these programs in a meaningful way from permanent pedestrian streets, and what role, if any, the special-event component plays in the programs. Methods A dual qualitative-quantitative mixed methodology was selected to evaluate Open Streets programs. First, a survey was constructed and provided to businesses that directly fronted the May 19th, 2013 Atlanta Streets Alive route. The purpose of this survey was to better appraise the impact that Open Streets programs may have on businesses in densely mixed-use corridors with a high representation of retail and restaurant establishments. As such, the survey included questions about the business’ sales receipts for the week prior, day of, and week following, the event. It also inquired about the business’ perceptions of the program, customer feedback, level of participation in the program, and awareness of the program, as well as general reception of the program and concept. It was made available to over 80 businesses by way of walk-in distribution of a link to the survey instrument (made available online to facilitate ease of completion for participants), as well as e-mail distribution and follow-up e-mails. The business survey supplements the central focus of the research, a comparative case study of 8 different recurring programs similar in concept (with a fair amount of variation) to Open Streets-style programs. The cases were selected on the basis of both their similarities and their differences, and include four large cities (Atlanta, Austin, Portland, and San Antonio) and four small/medium cities (Charleston, Macon, Rome, and Savannah). All but one of these cities has a program built around a street closure; the exception (Macon) was selected to better understand the role of street closures. As noted in the literature review, variation in program organization and operation is common, and the cases demonstrate this diversity. Nonetheless, they represent a range of applicable examples, and are more than sufficient to conduct a critical analysis of Open Streets programs as policy tools, as well as generate guidance for future program development. The case comparison was developed through document review and stakeholder interviews. Public documents (including annual and event reports, web pages, media publicity, and social media representation) were reviewed for each case, and a list of central stakeholders was generated (usually consisting of an organizing entity and/or municipality, and a primary sponsor). Secondary interview contacts were gathered from primary contacts, for a limited snowball interview technique. No less than two interviews were conducted for each given case, with some cases featuring three interviews based upon referrals from primary interview participants. Survey Results Despite reaching out to the full suite of merchants along the Atlanta Streets Alive program route through personal visits, email contact, and numerous followups both in person and via email, only ten merchants completed the survey. Of these ten, only seven fully completed the survey, so any discussion of the survey results is limited to some general observations and the discussion of specific responses from merchants who completed the survey. Of those businesses who reported revenue figures, only one business reported increased revenue on the day of Atlanta Streets Alive. At the same time, only two businesses reported a meaningful decrease in revenue, and one attributed this in large part to poor weather conditions (the day of the program was rainy until midway through the actual event). Of the nine businesses open on the day of the program (the tenth was a service firm), four reported higher than normal traffic in their business, another four less than normal traffic, and one the same level of traffic. This did not appear to be related to location, though 3 out of the 4 businesses reporting higher traffic were centrally located on the route, closer to activity centers. While a number of businesses along the route offered expanded seating, special activities, and other draws, none of the respondents reported any such efforts. One merchant was open on a day that would be otherwise closed for business, and reported that it was not worthwhile from a direct revenue perspective. Interestingly, of the five merchants who were independent merchants (i.e. theirs is a unique location) only one saw decreased foot traffic. Size of business (as measured through annual revenue) was similar across those with more traffic and less traffic. Awareness of the program amongst respondent businesses was fairly high (seven out of nine were aware of it beforehand), and they attributed their awareness to a range of exposure (including beverage reps, Atlanta Bicycle Coalition volunteers, employees, or previous experience with the program). Despite the mixed immediate results for respondent businesses, six out of the nine businesses who answered the question would support a return of the program to the corridor. One respondent noted that “sales are sales”, and encouraged a return of the program annually. None of the business reported any direct feedback from customers on the program. Table 4 identifies some positive and negative aspects of Open Streets from an economic development perspective, as well as lessons drawn from merchant responses and the case comparison that follows this section. Since the sample size is insufficient to speak in any statistically meaningful way, these points merely capture the range of positive and negative outcomes expressed and/or identified by respondents and stakeholders. While opportunities for increased revenue, visibility, and traffic are clearly presented by Open Streets programs, it’s also clear that it may increase the burden on businesses to be engaged, as well as hinder businesses that rely upon auto access (for example, there is a block of Peachtree featuring a high density of furniture stores), or businesses which are too close or too far from activity centers. Based on these positive and negative factors, some practical guidance can be crafted: firstly, that businesses should be actively involved in planning and should be encouraged to be engaged in the program in a way that matches their business. Secondly, secondary access routes may be critical for some businesses, and come-back coupons or other return incentives may also prove helpful. Thirdly, the placement of the route and activities matters, as activities may distract from adjacent businesses, but also draw participants to segments of the route. Table 4. Survey Lessons Pros Increased revenue and foot traffic for businesses actively engaging participants Cons May require additional hours and/or staffing Lessons Work with businesses to evaluate their needs and encourage businesses to be engaged Exposure to broad, semicaptive audience Consider secondary access routes, provide come-back coupons Environment supports window shopping, walk-ins Businesses reliant upon auto traffic (furniture stores, hotels) may require alternative access routes Activities may compete with businesses for attention Businesses along heavily visited sections of route saw high traffic Businesses farther from activity centers may see declined traffic Location of businesses along route matters; route must be carefully planned w/ businesses Offset activities from dense commercial blocks Case Comparison Case programs were selected to capture the variety of options available to an open streets program, to better convey the importance of certain commonalities as well as the suite of choices available when planning a new program and organizing its operation. Table 5 shows the differences between each of the case programs, from program route and frequency to cost and attendance. An annual orientation to programs is common, as many cities conceive of their program as an annual operation with one or more specific executions (which are not consistent in date or location). The two monthly programs stand out in this regard, as they reorient themselves throughout the year on a consistent basis. Route sizes and shapes also vary, though these cases all fall on the shorter end of the established range of programs identified in the literature. Cost also varies greatly, though it appears to scale with the size of the city, the scale of the program’s goals, and their ability to capture large sponsors. The most expensive programs were larger in route size, occurred more frequently (thus requiring ongoing organizational staff employment), and had more aggressive promotional campaigns. They also included more amenities, such as portable restrooms and free bottled water. While the largest programs dwarfed the others in cost, they also generated sizable crowds, and all had seen growing participation over the last few years. Smaller programs experienced smaller crowds, though more aggressive promotional campaigns seemed to draw larger crowds to even the smallest locations, as evidenced by the success of Charleston’s 2nd Sunday program which is promoted by the City, its sponsors, and all participating businesses. Table 5. Case Cities Title Frequency Route length Cost per occurrence Organizer Major sponsors Average attendance Cost per attendee Atlanta Austin Streets Alive 3x annually 2-6 mi Viva! Streets Annual San Antonio Siclovia Portland Charleston Savannah Rome Macon* 2nd Sunday on King Monthly Play Streets 2x annually Streets Alive Annual First Friday Monthly 1.5 mi 2x annually 2.2 mi Sunday Parkways Monthly (May-Sep) 6-9 mi .6 mi .2 mi .56 mi $35,000 $40,000 $75,000 $93,000 $9,000 $12,500 $2,000 ~1 sq mi $1,500 Nonprofit Coke, City Partnersh ip HEB, City Nonprofit HEB, City Public Non-profit Partnership Public Public Kaiser Permanent e, City King St Marketing Group Bike Walk NW GA 17,500 20,000 45,000 20,000 10,000 Partnership for a Healthier America 900 900 Robins Federal Credit Union 2,000 $2 $2 $1.66 $4.50 $.90 $13.9 $2.2 $.75 *Macon’s program does not include a street closure The organizational arrangements present in the case cities demonstrate some of the range of options available when considering an open streets program. Many of the most frequently recurring programs are operated by a public entity; since the recurring nature of the program demands continuing oversight and a close relationship with a municipality to manage street closures, permits, and the like, this might be expected. However, public entities are limited in their ability to collect sponsor donations and absorb the risks associated with the program. This means that partnerships are highly appealing, with even the public-led programs bringing in a smaller partner to absorb fundraising and liability. Some partnerships bring together a public entity and a private for-profit group, such as an event management firm. Others partner the public entity with a local non-profit. In three of the cases the non-profit actually took the lead, with a range of support and/or involvement from the local public entities. In two cases (Atlanta and San Antonio) the program began with greater public entity involvement, and then transitioned toward most of the operational burden being on the non-profit partner. In others, such as Portland, the public entity stepped up its involvement over time. In none of the cases was the public entity not involved somehow; likewise, all of them involve some level of participation from a partner non-profit organization. On the sponsor front, larger programs unsurprisingly had larger sponsors, with all programs reporting that they gathered larger sponsors as the program drew more attention and established itself in the community. Smaller programs more commonly identified one central sponsor who can support the program nearly in full in exchange for title rights and promotion. Larger programs instead featured a number of presenting sponsors who provide the central funding backbone and then a volume of additional sponsors to provide cash or in-kind support as possible. Sponsors identified a number of incentives to partner with a program, including shared goals, promotional value, and community interaction. Some sponsors have supported the program as a way to further their own mission or sub-mission, while others view it as a way to give back to their community and foster their image as community conscientious businesses. Program organizers noted the importance of setting clear program goals in order to provide a vision and guidance for organizing the program and evaluating its success. Table 6 depicts the goals for each program as identified by document review and interviews. The three most common goals are to increase physical activity, foster community interaction, and encourage economic development. Community development is the most common goal, followed closely by increased physical activity, then economic development. Four case cities identified either physical activity or economic development goals, but not both: this demonstrates that while there are opportunities to accomplish both goals in one program (note the other four cases listing both goals), the strategies may be different in many regards. Community development was prevalent regardless, while a number of other goals were present in only a few of the cases. Table 6. Program Goals Increase physical activity Economic Development Community Development Promote alternative transportatio n Promote parks/new facilities Encourage interaction across communities Atlanta Austin San Antonio Portland X X X X X X X X X Charleston X X X X Savannah Rome X X X X Macon X X X X X X X X Multiple interview participants noted the importance of pairing program features to program goals in order to maximize the impact of the program. For example, physical activity goals demanded a significant change to the space, hence the use of the road closure in all cases where that goal was present. The closure of the street provided space for participants to bike and walk freely, and also generated open space in which programs could hold a range of group activities such as Zumba, yoga, dance classes, soccer, basketball, and even special activities like rock climbing, clay sculpting, or “bad poetry reading”. The provision of group activity space was common, and while not strictly tied to community development goals, participants noted it as a valuable tool for fostering interaction. In the same way, economic development goals require close coordination and involvement with the business community to be fully effective. Among these cases that meant either extended hours and special deals, opening the business into the street (hanging clothing racks outside, expanding outdoor seating), providing special activities, or even special open container ordinances. Direct participation from community partners (local non-profits, advocacy groups, resource centers, faith-based orgs, etc.) was also very common, with interview participants noting it as a valuable tool for building relationships and drawing interest, as well as building civic awareness. Table 7 depicts the suite of general program features present in the case cities. Table 7. Program Features Atlanta Austin San Antonio X Portland Charleston Savannah Rome Road closure X X X X X X Business Involvement Dedicated group activity space Open shared space Community partner participation X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X Macon X X X While only five of the eight case cities had explicit development goals, all eight worked with the local business community as part of the program. In three cases this took the form of informing local merchants; the other five actively involved businesses in the program. Even those programs not specifically aiming to boost a business corridor were aware of the impacts that a street closure might have on businesses, and worked closely with local businesses to boost their awareness and provide them with opportunities to either boost business or at least reduce the undue impacts that the closure might have for them. Table 8 shows both the range of development strategies and the impacts observed for each case city. Among the three cities not seeking to generate development outcomes, these strategies were limited to contact with businesses during the planning phase. Nonetheless, these cities all reported a notable amount of positive feedback from businesses along their program routes, with some businesses reporting higher than normal traffic and/or sales figures, and consistent support from the businesses for returns of the program to the corridor. Table 8. Economic Development and Open Streets Developm ent Goals Development Program Strategies Business Impacts Observed Atlanta Yes Dense mixed-use corridor; businesses expanded hours, space, and activities, outside vendors excluded Austin No Contact with businesses during planning San Antonio No Portland Yes Charlesto n Yes Savannah No Rome Yes Contact with businesses during planning Outside vendors excluded, occasional inclusion of commercial corridor, business involvement Promotion, dense commercial corridor, expanded business space, close business cooperation, outside vendors excluded Contact with businesses during planning Ties into promotion of major annual event, dense commercial corridor Businesses which were actively engaged in some way (special activities, open doors, specials) have reported increased sales; mixed results from remaining businesses (though businesses along corridors have consistently asked for a return of the program or arrival of the program to their area) Some businesses reported higher traffic and exposure, others reported same as usual; appears that businesses more engaged in the program did better business Small retail and restaurant businesses have reported increased sales and traffic; businesses have all approved return of program each year Mixed responses; some corridors have had lower than normal traffic as potential clients are active rather than entering businesses (varies greatly among type of business). Also commercial density is low. Majority of businesses have reported it as their best Sunday of the year (60-65%), with additional businesses reporting their best day of the month. All businesses on corridor (regardless of direct sales boost) are supporters of program Macon Yes Promotion, dense commercial corridor, expanded space and hours, specials, close business cooperation Positive reception from the few businesses along route Some businesses have expressed increased sales and promotional benefits; others have reported that the clientele does not suit their particular business. Program occurs on Saturday, making it harder to increase sales over benchmark Mixed impact directly on businesses (program occurs on Friday night), though city has seen notable increase in interest in the area, with additional investment and development in downtown recently Among those cities seeking to generate development outcomes, popular strategies include the selection of a dense commercial corridor with sufficient residential density nearby to draw strong crowds, prominent and consistent promotion of the program through all media (particularly web, social media, and local news outlets), special business offerings (including extended hours, reduced prices, outdoor seating/shopping), and the exclusion of any outside vendors. Some programs worked closely with businesses that rely heavily upon auto access (such as furniture stores) to provide alternative routes, come-back coupons, and other incentives to boost their business through the program as well. Businesses have reported back to organizers mixed results in all cases, with a few consistent trends: First, businesses that are actively engaged in the program and take advantage of the crowds do much better sales days than normal, and much higher increases than other businesses. Also, retailers and restaurants consistently benefit the most from the programs, with other businesses seeing little direct impact. Finally, in all cases the program served to support a stronger community identity for the corridor, and many communities identified increased investment in the corridor over time since implementation of the program. Put another way, the programs all demonstrated some form of development outcomes, and were particularly effective where businesses took full advantage of the opportunity. Considering the positive development impacts, as well as the positive responses that all of the case programs reported from participants, local elected officials, and stakeholders, one might expect a high degree of interest in expanding the program. After all, if a semi-annual program is working, why not expand it? However, a common concern presented itself in the interviews: program dilution. It turns out, if the cases are any indication, there is an optimal balance between the advantages of a frequently recurring program (like public awareness, ease of planning, and compounding of outcomes) and the appeal that a “special event” has. In some cases, as they attempted to expand the program’s frequency they found that partners had a harder time devoting the same resources, and the impact of each single event was reduced. At the same time, the draw of the program was slightly reduced as it became too frequent, with less participants showing up than when the program was less frequent. The balance of this interest in expanding and the local reservations about expanding for each case are presented in Table 9. Table 9. Expansion Considerations Atlanta Austin San Antonio Portland Charleston Savannah Interest in expanding Aim to have program as regular as possible Split between interest in frequency and route size increases. Currently looking at increasing frequency and varying location Looking at new route choices and the possibility of having a more regular program Interest in expanding scale of program, not frequency. May consider additional neighborhoods however Residents want it more frequently, and have considered expanding it for holiday shopping season Some interest; currently aiming Reservations about expanding Cost is a barrier; also concerned about not reducing the special event appeal of the program without replacing it with the appeal of regularity Program requires a great deal of human and financial capital, plus an organizing entity that can devote to it Have to secure both the financial support and the needed manpower Concern about diluting program impact, and climate limits available months to hold the program Businesses worry about diluting its impact, and holding the program more often in past has seemed to reduce its appeal; also, closing street is complex and costly Funding is a serious challenge to overcome even Rome Macon just to maintain the program into future years Little interest, since program is paired to an annual event Attempted it, may consider again but likely not for some time just to maintain current program into future years Program is currently only tied to one event as a promotional bolster Previous attempt diluted impact of program and made it harder to operate Table 10 demonstrates that there is an optimal program frequency, and that it likely varies based upon competing programs, the size of the population, the locations of the program sites, and the scale of support available for the program. In almost every case the biggest barrier to even considering expansion (either to more dates or to bigger routes) was the difficulty of finding additional sponsors for the program. With sufficient support for the program, more frequent options become quickly available, as demonstrated by Savannah’s leap from an annual program in 2012 to a semi-annual program in 2013 thanks to a grant from a national partner. However, even once securing additional resources it appears to behoove organizers to consider the appropriate expansion strategy for their particular desired outcomes. Table 10. Optimal Program Frequency Pros Cons Participants and neighborhood groups Cost and volunteer requirements interested in expanding programs Increases health benefits to participants May dilute the uniqueness of the program, lead to declining attendance Expands audience, improves awareness Balance between frequency of program and size of program Recommendations New Program Suggestions Before undertaking an Open Streets program, a close partnership (or at least working relationship) must be formed between a local public entity and one or more community organizations (likely an existing non-profit with experience in event organization and operation). A non-profit is critical for soliciting and coordinating volunteers, securing donations and sponsors, and engaging with other organizations. Having a public entity involved will make it easier to secure street closures, work with local communities, and may provide the opportunity to reduce costs associated with closures, police officers, parks, and so forth. Identifying private entity sponsors should also be an early priority. Open streets programs are very diverse. As the lines between activity-based programs like Ciclovía and development-based street closure programs blur, the range of options for how a street closure might be employed as a policy tool only grow larger. As such, goal setting is a critical first step when constructing a program. While it may be appealing to take advantage of opportunities that arise to expedite program implementation (i.e. grants, political interest), without a clear set of program goals to guide program development and organization it will be much harder to maximize the value of the program. This goal setting process must also include all stakeholders, as their participation in the program will be directly related to the effectiveness of the program. Ideally, collaboration with stakeholders should begin as early as possible and actively encourage the identification of shared goals and opportunities for utilizing stakeholder resources (money, time, volunteers, inkind donations, direct participation) to accomplish those shared goals. Involving a diverse suite of stakeholders and participants offers the best opportunity for a successful program, and may lead to valuable partnerships beyond the program as well. Clear program goals can act as guidance when making decisions about program features. For example, visitors to a weekly program may have a harder time condoning higher than normal spending behavior, given that the program is a weekly event and they may return frequently. In addition, businesses have a harder time offering special deals and discounted prices every week than they do once a month. For programs like First Friday and 2nd Sunday, the monthly recurrence of the program becomes an opportunity to draw additional visitors. It also places a more reasonable financial and managerial burden on sponsors and program organizations. However, if the program’s goal is to maximize physical activity, then program frequency should be maximized to make the program a gateway to regular physical activity. Community development goals are also maximized by higher program frequency. Route distance, on the other hand, is not strictly critical to a development program (dependent upon impacts context), but may bridge a great number of communities with a longer route. On the other hand, a smaller loop may be more appealing for fostering physical activity, as it makes all activities closely available to any given participant accessing the program (though it may reduce the appeal of the route itself as the activity, in the case of runners and cyclists). Consider table 11: Table 11. Program structure suggestions Ideal Features Economic Development Goal Physical Activity Route location Consistency of location Program Frequency Route Length Prominent retail district No variation Mixed-use area Some variation Community Development Residential area Variation Monthly Weekly Weekly .5-1 mile (strip) 2-10 miles (loop) Program Features Variety of free niche physical activities Essential stakeholders Business involvement (specials, open seating, promotion) and coordination Local businesses, local municipality 1-5 miles (block or strip) Large open space, free public activities Road Closure At least partial closure Full closure Activity-based orgs, municipality Community orgs, places of worship, officials Full closure Table 11 displays some general direction for maximizing program impacts towards each of three possible program goals, based upon review of existing programs. By considering the opportunities for program overlap above, an organizing entity can construct a program to pursue their particular goals (though by no means is Table 4 exhaustive of all relevant considerations, nor is it presumed to be strictly correct in all cases). After selecting program goals, the organizer and partners should consider how the location might facilitate or limit the behavior they’d like to see generated (i.e. visiting businesses, talking with neighbors, or engaging in physical activities). Likewise review program activities, involved stakeholders, program frequency, promotional strategies, and program naming/branding. By matching the program to its goals, opportunities for overlap can be identified and conflicts avoided (for example, a program aiming for development and activity might anchor a route in a park within a dense retail district and locate activities in areas with less retail, as well as provide plenty of direct access to businesses so participants can be active and then relax by visiting restaurants and businesses). This matching is crucial for generating the maximum impact from a program, an ever-present goal given the tight competition for the resources of municipalities, sponsors, and non-profit partners. A final set of suggestions drawn from the case interviews concerns the task of program evaluation. Program evaluation varies widely across programs; the only fairly consistent measure of program success employed in all cases is attendance, with counting methods varying based upon available resources. Larger cities occasionally employed volunteers, local researchers, and/or contracted program operators to estimate other program impacts, but little in the way of standard operating procedures exists for such evaluation. Given the popularity of surveyed programs, particularly among local elected officials, it may be unsurprising that evaluation is not always prioritized. Nonetheless, it’s recommended that in addition to attendance estimates, program organizers should seek to survey businesses to assess their perceptions and immediate effects, and survey program participants to identify opportunities for improvement as well as more detailed info about program participants (I refer readers to Mason and colleagues’ (2011) discussion of program evaluation for detailed suggestions). Additionally, estimating physical activity changes and community development impacts, and using those findings as part of an iterative and critical learning process, will improve program operation and outcomes. While not exhaustive, the aforementioned suggestions capture the fundamental considerations that play into making an open streets program successful. Additional factors, such as the support of elected officials, learning from mistakes, the importance of getting it right the first time, and selecting dates that will reduce the likelihood of poor weather and conflicts, will all arise and play parts. The impact of these factors will be mitigated, however, by proper planning and a strong vision for the program which begins with a full suite of stakeholders, identifies explicitly its goals, structures the program features to match those goals, and then employs evaluation tools to assess the program and improve it for future occasions. Table 12 depicts the range of positive opportunities associated with Open Streets programs, as well as some of the most important requirements and considerations. Table 12. Takeaways Opportunities Increase physical activity of participants Opportunities for increased revenue and foot traffic Positive impact on local community o Foster community interaction Encourage alternative modes of transportation Encourage community collaboration Requirements Planning o Location & Frequency o Programming/Features o Road Closure Stakeholder Coordination o Planning o Engagement Promotion o Local media o Social media o Word of mouth Resources o Volunteers o Money Program Expansion Recommendations Reviewing the lessons of other programs offers suggestions not only to those locations which might consider developing a new program, but also to those programs which currently exist and may be beginning to face the barriers that stand between growing attendance figures, securing a major recurring sponsor, and the like. For these programs, an overhaul of planning may not be feasible or desirable, so instead attention must be paid to the components of the program that can be changed in the short term to foster long-term improvements. The first of these recommendations is to pay close attention to the selection of program locations. While it’s appealing in many cases to select a corridor that is in need of significant investment, it may lack the residential density and appeal necessary to easily draw large volumes of participants. Similarly, dense commercial corridors may provide programming and appeal, but as they lack the immediate population, connections may need to be planned to allow residents easy access to the program. Exciting corridors, particularly iconic streets or streets which have a cultural identity already, are good candidates for boosting the awareness of a program and drawing a base of participation, before considering less popular or populated corridors. Awareness is a major challenge for programs, particularly since the concept of Open Streets is not always easy to distinguish from events or other programs. Because of this, the use of aggressive promotional tactics is critical for spreading the word about the program and each specific occurrence. Consider involving local media (print, web, and television), a diversity of social media, and utilizing the media connections of all program partners. On that note, also be sure to continually pursue new partners and participants for the program. Not only will they help expand the breadth and scale of the program, but they may also serve to normalize the program and expand its audience. Look also to existing stakeholder participants who might not be fully utilized and work to engage them more actively in the program. Some businesses may feel that the program is not their clientele, but a clever activity or engagement of the crowd may secure them the interest of an entirely new clientele. Faith organizations, service firms, and others may not appear to be interested partners, but their involvement might be beneficial over the long term for all parties, and should be pursued. Be careful to target new audiences; enthused, active individuals will find and attend the program regardless, so it becomes most important to invest resources in ways that will reach new and perhaps underserved audiences. Consider unique promotional tools and opportunities. Finally, program sustainability is of critical importance. To this end, recurring sponsors are the ultimate goal, and should be courted aggressively by identifying opportunities for sponsorship and demonstrating program value clearly and consistently. In some cases one singular sponsor may be ideal; in other cases, a selection of smaller recurring sponsors will accomplish the same task. Either way, the value of being able to build a relationship with a sponsor and have the support needed to devote time between programs to evaluation and improvement is immeasurable. Develop a sponsor packet that clearly identifies how association with the program is beneficial, and how your program expects to expand its audience over time. Also be sure to court diverse sponsors including municipalities, elected officials, service firms, local corporations, national foundations, local merchants, and even individual citizens. Conclusions On the basis of the case comparison and the limited number of survey results, we can draw some general conclusions about the research questions. Each question was left intentionally broad at the outset, to allow for the potential variation in programs suggested at by the literature. The qualitative nature of the research methods also suggest speaking broadly about these specific cases, focusing on commonalities and differences as indicative of the significant findings. R1: How are Open Streets programs organized, and operated? What goals are associated with the programs? Cooperation and collaboration between one or more public entities and non-profit organizations appears to be central to the successful organization and operation of an Open Streets program. In some cases the program is operated by a public entity and other components outside the realm of local governments (fundraising, event management, volunteers) are managed by a non-profit. In other cases public entities are a support structure, providing resources, coordination, or other services to make the programs (operated by a non-profit) possible. In all cases the goals were very much public policy goals, including goals related to improving local economic development, transportation, public health, and community well being. R2: What benefits do stakeholders see from the programs? How do these benefits influence program structure, organization, and/or funding? In all cases the associated public entities saw community benefits, including increased activity and positive perceptions of their community. Sponsors, particularly the large private sponsors who were critical to the operation of the programs, displayed little interest in specifically influencing program organization or operation, but did attach themselves to programs to accomplish a range of their own goals. Most sponsors use the programs as community outreach efforts, with the added benefit of encouraging particular outcomes associated with their firm’s priorities (for example, two of the largest private sponsors both lead healthy living campaigns). For the non-profit partners, program features and activities are used to influence the outcomes associated with a program in ways that generally match their organizational priorities (for example, an athletic association focuses on group physical activities as a priority, a bike advocacy group on having large stretches of open street to ride and walk along). The level of involvement of business partners in planning appears to directly influence other merchants’ interest, and lead to programs excluding outside vendors but coalescing around special offers, outdoor seating, extended hours, and program promotion sponsored and facilitated by those businesses. Programs targeting economic development goals appeared far more successful at realizing those benefits when businesses were fully involved, not just informed. Finally, location decisions play a part in realizing particular benefits, as an effective economic development strategy requires the appropriate commercial corridor; likewise, a physical-activity strategy requires a diversity of activities and residential density. R3: How do Open Streets impact businesses along the route? Across the limited number of business surveys collected, as well as the comments of case program stakeholders, business impacts varied widely. Most programs reported anecdotal increases in traffic and revenue at businesses, with some programs resulting in the busiest business days of the year. At the same time, programs are far more effective for retail and restaurant establishments than other merchants, and merchants who invested the resources to actively engage program participants appear to be more successful at seeing returns than do businesses that operate as usual. It appears that program organization, promotion, and the level of involvement on the part of businesses are all tied to the effectiveness of Open Streets as an economic development program. R4(a): What factors influence the frequency of recurrence of Open Streets programs? R4(b): Is there interest on the part of stakeholders to increase the frequency of the programs? For programs operating at an annual or semi-annual frequency, interest in expanding frequency was high. Many reported an interest in holding programs throughout the warm weather months. However, amongst those programs already holding a monthly program (or a monthly program during the warm seasons), there was less interest in expanding (though some interest remained). Despite the different levels of enthusiasm for expanding program frequency, all respondents noted a lack of resources as the biggest barrier to expansion, particularly the cash and staff time needed to hold a program more frequently. They also noted the value of having the program infrequently enough to make it a special attraction. Development-oriented programs in particular require promotion and a level of uniqueness to draw participants, and organizers reported program dilution as a serious concern at a certain level of frequency. This dilution concern was less common among programs focused primarily on fostering physical activity, where a recurring program offers more meaningful impacts on behavior than a less frequent special program. This leads to one additional common sentiment expressed by many participants when discussing outcome goals: Open Streets as part of a movement. It was noted by participants that while their programs did have meaningful direct impacts, that their primary vision for the program was that it would actually spur more meaningful, ongoing changes in behavior and perspective. Some groups hoped that their programs would open participants’ minds to biking and walking as means of transportation, while others wanted to showcase the enjoyment of exercise and the please of spending time in a previously undervalued neighborhood or commercial corridor. These larger projects, of building stronger community and changing perspectives as well as behaviors, are less tangible in their immediate benefits, but may be instrumental parts of larger long-term policy strategies. Although Open Streets programs offer significant opportunities, they are not without their own challenges and obstacles. The scale of resources needed for an effective and sustainable program is not to be underestimated, and effectively engaging a community is a sizable and ongoing challenge. At the same time, as part of a long-term strategy to effect meaningful change in a community, Open Streets suggest a creative strategy that can be tailored to the unique, diverse needs of any particular community. In this regard, they represent a creative, pragmatic tool to both generate and employ collaboration to positive effect. By working within the intersection of multiple broader issues (and at a more human level), they may be more successful at combating feedback mechanisms and addressing these complex challenges. Future efforts to assess how unique conditions have led programs to take the form they have, as well as to more successfully quantify the impact on outcomes (particularly business impacts), will offer additional opportunities to better understand these programs. In the meantime, it appears that the growing interest in such programs as policy tools is unlikely to decline. References Brown, C., Hawkins, J., Lahr, M. L., & Bodnar, M. (2012). The Economic Impacts of Active Transportation in New Jersey. Cattell, V., Dines, N., Gesler, W., & Curtis, S. (2008). Mingling, observing, and lingering: everyday public spaces and their implications for well-being and social relations. Health & place, 14(3), 544–61. Cervero, R., Sarmiento, O. L., Jacoby, E., Gomez, L. F., & Neiman, A. (2009). Influences of Built Environments on Walking and Cycling: Lessons from Bogotá. International Journal of Sustainable Transportation, 3(4), 203–226. Clifton, K. J., Muhs, C., Morrissey, S., Morrissey, T., Currans, K., & Ritter, C. (2013). Examining Consumer Behavior and Travel Choices. Crompton, J. L., Lee, S., & Shuster, T. J. (2001). A Guide for Undertaking Economic Impact Studies: The Springfest Example. Journal of Travel Research, 40(August), 79–87. Diaz del Castillo, A., Sarmiento, O. L., Reis, R. S., & Brownson, R. C. (2011). Translating Evidence to Policy: Urban Interventions and Physical Activity Promotion in Bogota, Colombia and Curitiba, Brazil. Translational Behavioral Medicine, 1, 350–260. Feehan, D. M., & Becker, C. J. (2011). Pedestrian streets, public spaces, and Business Improvement Districts. Journal of Town & City Management, 2(3), 280–286. Gursoy, D., Kim, K., & Uysal, M. (2004). Perceived impacts of festivals and special events by organizers: an extension and validation. Tourism Management, 25(2), 171–181. Handy, S. (1993). A Cycle of Dependence: Automobiles, Accessibility, and the Evolution of the Transportation and Retail Hierarchies. University of California. Hipp, A., & Eyler, A. (2012). Open and shut: the case for Open Streets in St. Louis. St. Louis. Hipp, J. A., Eyler, A. a, & Kuhlberg, J. a. (2012). Target Population Involvement in Urban Ciclovías: A Preliminary Evaluation of St. Louis Open Streets. Journal of urban health : bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine, 1196(68899). Hyland, A., Cummings, K. M., & Nauenberg, E. (1999). Analysis of Taxable Sales Receipts: Was New York City’s Smoke-Free Air Act Bad for Restaurant Business? Journal of Public Health Management Practice, 5(1), 14–21. Lal, R., & Matutes, C. (1994). Retail Pricing and Advertising Strategies. The Journal of Business, 67(3), 345–370. Leyden, K. M. (2003). Social capital and the built environment: the importance of walkable neighborhoods. American journal of public health, 93(9), 1546–51. Litman, T. A. (n.d.). Economic Value of Walkability. Transportation Research Record, 1828(03), 3–11. Lugo, A. E. (2013). CicLAvia and human infrastructure in Los Angeles: ethnographic experiments in equitable bike planning. Journal of Transport Geography. Mason, M., Welch, S. B., Becker, A., Block, D. R., Gomez, L., Hernandez, A., & SuarezBalcazar, Y. (2011). Ciclovía in Chicago: a Strategy for Community Development to Improve Public Health. Community Development, 42(2), 221–239. Montes, F., Sarmiento, O. L., Zarama, R., Pratt, M., Wang, G., Jacoby, E., Schmid, T. L., et al. (2012). Do health benefits outweigh the costs of mass recreational programs? An economic analysis of four Ciclovía programs. Journal of urban health: bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine, 89(1), 153–70. PBOT. (2008). Sunday Parkways: Manual and Final Report December 2008. Portland. Pucher, J., Dill, J., & Handy, S. (2010). Infrastructure, programs, and policies to increase bicycling: an international review. Preventive medicine, 50, S106–125. Rittel, H. J., & Webber, M. M. (1973). Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning. Policy Sciences, 4, 155–169. Robertson, K. a. (1997). Downtown retail revitalization: a review of American development strategies. Planning Perspectives, 12(4), 383–401. Sarmiento, O., Torres, A., Jacoby, E., Pratt, M., Schmid, T. L., & Stierling, G. (2010). The Ciclovía-Recreativa: A Mass-Recreational Program with Public Health Potential. Journal of Physical Activity and Health, 7(Supplement 2), 163–180. SFMTA. (2011). 2011 Season Highlights: Sunday Streets San Francisco. Street Plans, & Alliance for Biking and Walking. (2012). The Open Streets Guide. Torres, A., Sarmiento, O. L., Stauber, C., & Zarama, R. (2013). The Ciclovía and Cicloruta programs: promising interventions to promote physical activity and social capital in Bogotá, Colombia. American journal of public health, 103(2), 23– 30. Wright, L., & Montezuma, R. (n.d.). Reclaiming Public Space: The Economic, Environmental, and Social Impacts of Bogotá’s Transformation. Zieff, S. G., Hipp, J. A., Eyler, A. a, & Kim, M.-S. (2013). Ciclovía initiatives: engaging communities, partners, and policy makers along the route to success. Journal of Public Health Management Practice, 19(3), S74–82. Zieff, S. G., & Kim, M.-S. (2010). Reaching Targeted Participants in an Urban Ciclovía: The Case of Sunday Streets San Francisco. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 42(5(supplement 1)), 654. Zieff, S. G., Wilson, J., Kim, M., Tierney, P., & Guedes, C. M. (2010). Meeting Physical Activity Guidelines through Community-Based Events: The Case of Sunday Streets. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 42(May), 654.