Values, Culture and the Thai International Education Experience

advertisement

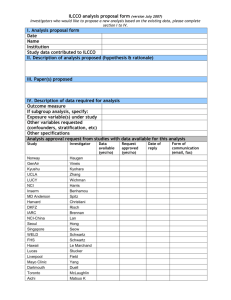

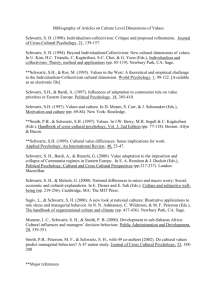

Values, Culture and the Thai International Education Experience. Sean A. Gallagher, Mahidol University International College Abstract: The cross culture management literature abounds with journals measuring cultural variability between countries using a variety of value based dimensional models and providing subsequent prescriptive management advice for improved cross cultural understanding and operating synergies. These models however have not explicitly assessed the impact of the growing international education phenomenon on international students’ values, a privileged population segment that have significant influence in international organizations in their countries. This paper is exploratory and aims to initiate research on the impact an international education has on indigenous cultural value orientations, specifically between Thai international students who have studied in an Anglo-cluster country and Thai domestically educated students, using a Schwartz Value Survey. Schwartz’s national culture dimension embeddedness was the only dimension to show statistically significant difference between the two groups’ means with Thai international participants embracing traditional Thai values to a greater extent than the both domestically educated Thai participants and the Thai population in general. 1 Introduction: Operating internationally is a challenge not only faced by multinational companies (MNC). Many non governmental organizations (NGOs), non profit organizations and governmental bodies engage internationally and in doing so must deal with a variety of cultures. When international collaboration is conducted, invariably the participants bring with them diverse cultural predispositions which can affect the results of the interaction (Graham et al., 1994). The cross-culture management literature abounds with journals investigating cultures influence on management and other areas of organizational behavior including growth strategies: entry mode decisions (Arora and Fosturi, 2000), foreign investment decisions (Tahir and Larimo, 2004), research and development decisions (Muralidharan and Phatak, 1999), international consumer behavior: consumer innovativeness (Steenkamp et al. 1999), impulse buying (Kacen and Lee, 2002) and negotiation behavior: intra and intercultural behavior differences (Adler and Graham,1989), culture and its effect on joint gains (Brett et al., 1998), culture/ethnicity influences on the negotiating styles of Asian managers (Aahad, Osam-Gani and Tan, 2002). The importance of culture and values to management behavior is well documented and substantiated through research across management disciplines (Hofstede, 2001). In the majority of these studies researchers have treated national culture as a predictor variable and used etic value based cultural dimensions to identify differences in culturally normative behavior, behaviors manifest in tendencies for certain culturally normative management norms. For example the preference for conflict management approaches among countries high on individualistic values, such as the UK or Canada, are often very different than more collective value oriented relationship focused Asian countries (Morris et al., 1998). These etic comparative value based models however have not explicitly assessed the impact of the growing international education phenomenon on an exclusive, privileged sample of the population, the internationally educated, a segment that makes up a significant proportion of decision makers and negotiators in MNC, government agencies and NGOs. This paper aims to assess the impact of an international education on indigenous value orientations of Thai international undergraduate and graduate students who have studied in an Anglo-cluster country using a Schwartz Value Survey. It is hoped that through an improved understanding of the effects of international education on cultural values, researchers, students and management practitioners will better understand the potential for variance from presumed culturally normative behavior resulting from this international education phenomenon. 2 International Education Trend: Globalization has had a profound impact in the internationalization of business, including the internationalization of the business of education which has taken a place as an important commodity bought and sold around the world. This trend in the demand for international education has attracted the attention of the international world community’s governing bodies. The World Trade Organization has included ‘educational services’ in the negotiations of The General Agreement on Trade and Services (GATS)(Larsen, 2002). Many OECD countries have commercial motives behind policies to attract foreign students primarily as a policy to both pass on escalating costs of tuition to foreign students while maintaining domestic fees, as well as increasing the cultural diversity in the educational system (Larsen, 2002). This paper does not consider the policy implications of education becoming a tradable commodity but does consider the geographical areas in which this trade is flourishing and its affect on student participants. Demand for education, particularly higher education, has traditionally been driven by expectations of its ability to raise the economic and social status of the graduate. For people in less developed countries, limited access to education in their own countries has led to a significant rise in the number of international students studying overseas (Mazzarol & Soutar, 2002).According to the Australian Government (2008), the majority of foreign students choose to undertake their international education studies in OECD countries. The 2005 OECD Report on International Education stated that this region accounted for approximately eighty percent of all international education destinations (OECD, 2005). Six countries, USA, United Kingdom, Australia, Germany, France and Japan accounted for more than three quarters of this number. Even more significant is that in the same year just fewer than fifty percent of all foreign students studying in OECD countries chose English speaking Anglo-cluster OECD countries.1 Australia is conspicuous in its success in recruiting international students. The number of foreign students studying in Australia tripled from 1990 to 2002, multiplying thirteen fold since 1980 (OECD, 2002). Regionally, Asia is the biggest contributor of foreign students to these Anglo cluster English speaking countries (OECD, 2006). As seen from the Table 1, Thailand, in 2005, had 22,066 students studying in OECD countries with 83 percent of the total number of Thai international students studying in Australia, New Zealand, United Kingdom, or United States. term denoted for a cluster of countries with significantly similar values and norms which includes Australia, UK, USA, Canada and New Zealand (Ronen and Shenkar 1985) 1 3 Table 1: International Student Numbers in Australia, New Zealand, United Kingdom and United States Australia New Zealand United Kingdom USA Countries of Origin Total % students studying in Anglo cluster countries Percentage of students studying in the 4 Anglocluster countries Total international students OECD destination s Market share 2000 6.5% 2.5% 11.7% 21.6% 42.3% Market share 2005 5.8% 0.5% 12.3% 26.1% 44.7% Thailand 4,923 453 3,940 9,021 18,337 83.1% 22,066 China 37,344 23,260 52,677 92,370 205,651 57.9% 355,377 India 20,515 1,563 16,685 84,044 122,807 93.6% 131,178 Hong Kong 12,703 436 10,780 7,499 31,418 99.9% 31,465 Lao PDR 111 1 11 66 189 28.8% 655 Malaysia 15,552 1,190 11,474 6,415 34,631 89.3% 38,784 Myanmar 194 20 202 680 1,096 59.2% 1,852 Philippines 732 81 955 3,688 5,456 79.7% 6,842 Singapore 10,105 209 3,628 3,937 17,878 97.1% 18,415 Viet Nam 2,755 492 1,111 3,833 8,192 44.4% 18,432 (Source: OECD, 2005) The OECD (2006) report shows that in Asia the majority of students looking for international education chose English speaking countries primarily Australia, United Kingdom, USA and New Zealand. Pimpa suggested this was the case because of the perception that international education in these countries is of higher quality, offers the opportunity to gain fluency in a foreign language especially developing English language skills and understand western practices and culture, and receive improved status in the local employment market (2002). But what is the effect of international education, specifically Anglo cluster based, on the Asian international student’s primary cultural values and beliefs and eventually their terminal management behaviors? It is the goal of this exploratory paper to contribute some initial understanding to the relationship between international education and indigenous values of the internationally educated student. Further research is currently being undertaken to qualitatively assess the effect this international education has on international students through simulated negation exercises. This research is ongoing. 4 In order to understand the importance of this potential mediating variable, a further understanding of values and culture need to be addressed.In the following section an explanations of culture is presented followed by an explanation of value theory, some prominent cultural based (etic) frameworks used by researchers to operationalize culture, as well as the current literature’s assessment of cultural differences between Thailand and some Anglo cluster countries. Values and Culture: National culture has long been acknowledged as significant in explaining behavior (Hofstede, 1980). As a comparative tool, national culture has also been used to assess difference in behaviors across different countries and in doing so in organizational behavior (Ng. et al., 2006). Researchers from this etic oriented perspective, view the study of multiple cultures through a trans or meta approach perspective as opposed to the emic approach which examines culture from the examinee’s perspective. The etic approach requires a descriptive classification scheme that allows differences and similarities of underlying cultural constructs to be visible across cultures (Helfrich, 1999). Theorists affiliated with the etic school view culture as a factor of influence and operationalize variables to test across cultures in an attempt to explain the influence specifically through the differences in cognition, behaviour and learning (Helfrich, 1999). Cultural values have been the basis of these constructs to measure culture and the associated cultural variability. Values represent the implicitly or explicitly shared abstract ideas about what is good, right, a desirable in a society (Williams, 1970). “These cultural values (e.g. freedom, prosperity, security) are the bases for the specific norms that tell people what is appropriate in various situations. Because cultural value priorities are shared, role incumbents in social institutions (e.g. leaders in governments, teachers in schools, executive officers of corporations) can draw on them to select socially appropriate behavior and justify their behavioral choices to others ( e.g. to go to war, to punish a child, to fire employees)” (Schwartz, 1999 pg25). To use value theory in cross cultural studies, a theory of value dimensions on which the cultures of nations can be compared and measured is a necessity (Schwartz, 1999). Researchers use values as independent variables to understand attitudes and behaviors. More commonly though as dependent variables to measure basic differences among groups and societies by way of formulating common dimensions of culture and using these dimensions to measure similarities and differences across and between cultures (Spini, 2003) The most pervasive value mapping approach used is Hofstede’s four value dimensions of Individualism/Collectivism, Power Distance, Uncertainty Avoidance, and Masculinity-Femininity. Individualism/ Collectivism dimensions represent the relationship between the individual and the group in society; individualists prefer a loose social network where individuals take care of themselves and immediate family only while collectivists prefer a more tightly knit social framework where in-groups define the individual and will provide support in exchange for loyalty and commitment. Power distance measures the expectations regarding equality among people; high power distance cultures accept hierarchical order and the powerful need not justify these inequalities while low power distance cultures strive to reduce the inequality in society. Uncertainty avoidance measures the degree members of a society feel comfortable with ambiguity and 5 uncertainty; high uncertainty cultures enforce codes of behavior which promote certainty and protect conformity while low uncertainty cultures maintain a more relaxed attitude towards behavior and deviance is more tolerated. Masculinity/ Femininity measures how society attributes social (as opposed to biological) roles to the sexes with masculine cultures preferring values such as achievement, assertiveness and material success while feminine cultures prefer values such as relationships, caring for weaker members, and quality of life(Hofstede, 1980). The Hofstede dimensional model is employed in numerous cross discipline studies to organize and explain cultural constructs (Bond and Leung, 2004) with work replicating the validity of Hofstede’s dimensions and their encompassment of work related values numbering over 15 000 published studies (Bird and Metcalf 1987). To include values significant to Chinese people, a further dimension was added called the Confucian Work Dynamism or short term versus long term orientation (Hofstede, 1991). Subsequent to Hofstede’s (1980) pioneering work, several other major cross-cultural frameworks have been derived including Smith, Dugan, and Trompenaars (1996) two value dimensions at the cultural level consisting of egalitarian commitment versus conservatism, and utilitarian Involvement versus loyal involvement, and House et al. (2003) identification of nine culture-level dimensions including performance orientation, assertiveness orientation, future orientation, humane orientation, institutional collectivism, family (now In-Group) collectivism, gender egalitarianism, power distance, and uncertainty avoidance. Schwartz Value Survey An increasingly popular etic framework is the Schwartz (1994) human values framework. This national culture framework was developed from the 57 individual value Schwartz Value Survey (SVS). Of the 57 individual value items in the SVS, only 45 were found to have consistent meaning at an individual level; as a result, only these 45 items were employed in a national level of analysis (Schwartz, 2008). Using multidimensional scaling procedures, inter-correlations between values were examined. From this analysis seven culture value types were found and summarized into three dimensions. These three dimensions included: 1. Embeddedness versus autonomy: The nature of the relations and boundaries between the person and the group; the extent to which people are autonomous or embedded in their groups (Schwartz, 2006) 2. Hierarchy versus egalitarianism: The nature of maintaining and preserving the social fabric of society; a hierarchical system of ascribed roles or recognizing each other as moral equals and committed to cooperate for everyone’s welfare (Schwartz, 2006). 3. Mastery versus harmony The regulation of human and environmental resources, the nature to master, direct, and change the natural and social environment to attain group or personal goals or fitting into social and natural world without incentive to change it. (Schwartz, 2006) The seven culture level value types follow from these 3 dimensions as Schwartz (1994) defined them are: 6 1. Embeddedness. A society that emphasizes close knit harmonious relations, the maintenance of the status quo and avoids actions that disturb traditional order. 2. Intellectual autonomy. A society that recognizes individuals as autonomous entities who are entitled to pursue their own intellectual interests and desires. 3. Affective Autonomy. A society that recognizes individuals as autonomous entities who are entitled to pursue their stimulation and hedonism interests and desires. 4. Hierarchy. A society that emphasizes the legitimacy of hierarchical roles and resource allocation. 5. Mastery. A society that emphasizes active mastery of the social environment and individual’s rights to get ahead of other people. 6. Egalitarian Commitment. A society that emphasizes the transcendence of selfless interests. 7. Harmony. A society that emphasizes harmony with nature. Schwartz (1994) suggested that this 7 cultural value type framework included all of Hofstede’s dimensions while Brett and Okumura (1998) claimed Schwartz’s value types may be able to explain greater cultural variation between countries and thedimensional framework to be superior to the widely used Hofstede work for three reasons: the framework is based on a conceptualization of values, systematic sampling measurement and analysis techniques were employed when developing the model and the data is more recent. Thailand and Anglo Cluster Values: Cultural theorists such as Hofstede and Triandis point out that Thailand and Anglo cluster countries differ dramatically in their cultural values, accepted norms and behaviors. Hofstede’s (1980) dimension analysis points to significant differences in power distance or inequality in society. Schwartz measures the same construct through the Egalitarianism and Hierarchy dimension with Thailand having higher hierarchy value priorities. Further, Triandis and Hofstede assert that the Thai collectivist value priorities are very different than the more individualistic values of Anglo cluster countries. Schwartz measures the same construct through Embeddedness and Autonomy with Thailand having higher Embeddedness value priorities (Schwartz, 1994). Hofstede’s dimensional analysis is an often cited study for investigating cultural differences in many functional management areas. In Table 2, Noypayak and Speece (1998) summarize the differences in cultural values for Thailand and 2 the Anglo-cluster countries, the United States and the United Kingdom using Hofstede’s framework. The largest differences in cultural values was individualism/collectivism (Anglo very high), power distance (Thailand very high) and femininity (Thailand much more feminine). 7 Table 2: Hofstede’s Cultural Dimensions for Thailand, the USA, and UK A B C D E Individualism 20 39-41 91-89 1-3 Power distance 64 21-23 40-35 38-43 Uncertainty 64 30 46-35 43-47 34 44 62-66 15-10 Avoidance Masculinity Source: Hofstede (1994) A = Dimension, B = Thailand: score, C = Thailand: rank, D = USA, UK: score, E = USA, UK: rank, F = Thailand compare to USA, UK In this research, the Schwartz national culture level dimensions will be employed as a comparative tool to measure the value orientations between groups of internationally educated Thai students and domestically educated Thai students principally to determine if the foreign education experience has initiated a discrepancy in cultural value orientations between the two focused groups. Further, the analysis will also be compared to Schwartz’s value orientation rankings for Thailand, and the value/dimension rankings for the Anglo-cluster countries that these international students attended specifically United Kingdom, New Zealand, Australia, Canada and the United States. Participants: In the present study the participants were 85 students from Mahidol University and Thammasat University in Bangkok, Thailand. To produce comparable results to Schwartz’s sample, I chose students studying in either the undergraduate business courses or the MBA program. Schwartz’s focus on samples was urban school teachers who taught the full range of subjects from grade 3- 12 of the most common type of school in each of the 44 nations researched and college students from a variety of majors (Schwartz, 1999). These teachers would presumably have master degree education. The goal of this sample selection was to select a group who would most probably reflect the mid-range of prevailing value priorities in society. Table 3 displays some descriptive statistics of the sample group. Buddhism was the dominant religious group with 90 percent of participants, Christianity 3.5 percent, Islam 2 percent, no religious affiliation 2 percent and Hindu and Other both with 1 percent. 8 Table 3: Descriptive Statistics for Foreign Educated and Domestically Educated Sample Number Average Percentage Percentage Participants Age (years) Female Male Foreign Educated Sample 34 25.4 44% 56% Thai Educated Sample 24.1 61% 39% 51 Measures: The respondents completed the 57 item Schwartz Value Survey (SVS) at their university in class time and means were calculated for each of the seven cultural dimensions for both the international educated Thai group and the domestically educated Thai group. To compute the mean importance of the seven dimensions, an average was calculated for the importance the members of the sample gave to values which represented one of the seven dimensions. For example, the mean importance of Hierarchy is the average of the ratings of the survey questions pertaining to Social Power, Wealth, Authority, and Humble. See Table 4 for the value calculations for each of the seven dimensions. Table 4: Schwartz’s 7 National Culture Scoring Key Questions used from 57 Item SVS to calculate Cultural level Embeddedness means for each Schwartz’s 7 dimensions. 8,11,13,15,18,20,26,32, 40, 46,47,51,54,56 Hierarchy 3,12,27,36 Mastery 23,31, 34,37,39, 41,43,55, Affective Autonomy 4,9,25,50,57 Intellectual Autonomy 5,16,35,53 Egalitarianism 1,30,33,45,49,52 Harmony 17,24,29,38 9 To correct for cross national comparisons, the mean was standardized for each country’s dimensions around an approximate international mean of 4.00. The participants were offered the SVS in either Thai or English language. The mean scores for Schwartz’s seven dimensions and the participating Anglo-cluster countries, and Thailand are set out in Table 5. Table 5: Mean Scores for Schwartz’s National Dimension of Culture for Thailand and Anglo Cluster countries Country Harmony Mastery Egalitarianism Hierarchy Intellectual Embeddedness Autonomy Australia 3.99 3.97 4.79 2.29 4.35 3.59 New Zealand 4.03 4.09 4.94 2.27 4.65 3.27 Canada 3.91 4.08 4.85 2.04 4.58 3.38 United Kingdom 3.91 4.01 4.92 2.33 4.62 3.34 United States 3.46 4.09 4.68 2.37 4.19 3.67 Thailand 3.68 4.01 4.18 3.27 4.03 3.92 Hall and Gingerich (2004: p.14) Discussions: This exploratory study was designed to investigate the effect an international education had on the cultural values of Thai international students using a Schwartz Value Survey. Although there are many limitations to this research, which will be discussed further, the overriding purpose was to initiate further research using both quantitative and qualitative techniques to investigate this phenomenon. The unit of analysis for testing the relationship between the international educated sample and the domestically educated sample was the national culture measured by the means of Schwartz’s seven dimensional framework (Table 4). To test whether the means of the two groups were statistically different from each other on each of the seven dimensions a simple t-test was employed. The results of the t-test were conclusive on only one dimension embeddedness at a significance level of .05. The T-test results for all 7 dimensions are listed in Table 7. 10 Table 6: Mean Scores for Schwartz’s National Dimension of Culture for Thai Domestically Educated Students and Thai Internationally Educated Students Country Harmony Mastery Egalitarianism Hierarchy Intellectual Embeddedness Autonomy Internationally 3.7206 4.2574 4.6520 3.3309 4.1691 4.4375 Domestically Educated 3.4216 4.4069 4.7516 3.1127 4.4804 3.8641 Thailand 3.68 4.01 4.18 3.27 4.03 3.92 Educated Table 7: T-test For Equality of Means (95% Confidence Interval) Schwartz’s National Dimension t df Sig. (2-tailed) 83 .002 3.215 Embeddedness Mean Difference .57331 Hierarchy .696 83 .488 .21814 Mastery -.825 83 .412 -.14951 Affective Autonomy -.760 83 .450 -.20588 Intellectual Autonomy -1.344 83 .183 -.31127 Egalitarianism -.477 83 .635 -.0996 Harmony 1.054 83 .295 .29902 Two important aspects of these results immediately drew attention. First, the individual vs. group orientation of Embeddedness and Autonomy (Hofstede’s Individualism and Collectivism) was seen to be the only dimension to show substantial variability in means (See Table 6). Prior research has shown that differences in this dimension appear to be the most significant cultural difference among national cultures with well over 100 publications per year using this dimension in discussing cultural differences across multiple research fields (Greenfield, 2000). It is also interesting to note that Hofstede’s analysis of the 4 dimensions showed that individualism and collectivist values were very different for Thai and Anglo cluster cultures. Although the two sample groups’ means did not show statistical significance in the Autonomy dimension, there was variance in means and deserves further investigation with larger sample sets (See Table 6). The Embeddedness dimension however showed statistical significance in the means between the two sample groups and is a major finding when analysing the effect of international education on Thai students. 11 This leads to the second interesting result. Against intuitive expectations, the international students’ embeddedness means were higher than the domestically educated students and the Thai population in general and the Autonomy means were lower than the domestically educated students and equivalent to the Thai population in general. In fact, this would suggest that after an international education experience, Thai students embrace more traditional Thai values, even to a greater extent than the domestically educated students. In fact Thai international students become more embedded in their cultural in-group and show even less individualistic tendencies, even after exposure to a culture with high individualist and lower collectivist values. This deserves further attention because current research suggests (Pimpa, 2002) that Thai students choose Anglo cluster countries because of the social desirability of the experience in the workplace, better jobs and workplace status, but upon their return apparently reject the values and norms of the countries in which they underwent this educational experience. The fear that students studying internationally will eventually lose their ‘culture’ may need to be reevaluated. Conclusions and Further Research: The international education experience is a phenomenon that is under researched in the cross cultural management field. In Asia, an internationally educated student, particularly from Anglocluster countries, is in high demand by commercial, governmental and non-government organizations. Much of the cross-cultural management literature centers on assessing national cultures and offering prescriptive advice for executives and workers to function effectively in that culture. If the management ranks of many of these organizations are filled with internationally educated professionals, then the mediating variable of international education needs to be factored into the theory. This research has demonstrated initially that the returning international student does show some cultural dimension variability most noticeably in the individualism/collectivism construct, embracing embeddedness value orientations to a greater extent than both domestically educated Thai students and the population in general. An area of study that could be developed is to approach this international education phenomenon through cultural syndromes, specifically applying a bi-dimensional/multidimensional perspective such as Triandis’ individualism/collectivism, horizontal/vertical approach (Triandis, 2000). This would measure both the individualism and collectivism dimension but also capture the hierarchy/ egalitarianism dimension that also showed some variability in means, although not statistically significant, between the internationally and domestically educated participants. Another area of study that could be incorporated into this area of research is the students’ participation in international schools, institutions that serve to provide domestic Thai students, and international students, the opportunity to learn in an environment closely resembling that of the Anglo cluster which the education standards are derived. Limitations: The author realizes there are serious limitations to the current research. The sample not only needs to be substantially larger but also should have equal representation of internationally educated Thai 12 students and domestically educated Thai students. Also the percentage of males and females internationally educated was asymmetric. Further a more structured approach needs to be taken regarding both countries of international education as well as time spent in that Anglo cluster international environment. References: Adair W. L. and Brett J. M. (2005) The Negotiation Dance: Time, Culture, and Behavioral Sequences in Negotiation. Organization Science 16(1), pp. 33–51 Adair, W.L., Brett, J.M., Lempereur, A., Okumura, T., Shikhirev, P., Tinsley, C., and Lytle, A. (2004). Culture and negotiation strategy. Negotiation Journal, January: 87-111. Adair, Wendi L. & Brett, J. M. (2002). Culture and negotiation processes. In Michele J. Gelfand and Jeanne M. Brett, (Eds.), Culture and Negotiation: Integrative Approaches to Theory and Research. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press. Adair, W.L., Brett, J.M., Lempereur, A., Okumura, T., Shikhirev, P., Tinsley, C., and Lytle, A. (2004). Culture and negotiation strategy. Negotiation Journal, January: 87-111. Adair, W., T. Okumura, T and Brett, J.M. (2001). Negotiation behavior when cultures collide: The U.S. and Japan. Journal of Applied Psychology 86(3): 371–385. Adler, N.J., Graham, J.L. (1989). Cross cultural interactions: The International comparison fallacy. Journal of International Business Studies, Fall 1989 Alon, I. & Brett, J.M. (2007). Perceptions of time and their impact on negotiations in the Arabicspeaking Islamic world. Negotiation Journal, January 55-73 Australian Government: Australian Education International [Online] October 1, 2007 http://aei.dest.gov.au/AEI/PublicationsAndResearch/MarketDataSnapshots/MDS_No03_Thai_pdf.p df Australian Government: Reserve Bank Bulletin [Online] June 1, 2008 http://www.rba.gov.au/PublicationsAndResearch/ Bird, A. & Metcalf, L. (2004) Integrating twelve dimensions of negotiating behavior and Hofstede’s work-related values: A six country comparison. 13 Bird, A. & Osland, J.S. (2005). “Making Sense of intercultural collaboration”. International Studies of Management and Organizations, 35 (4) Centre for Educational Research and Innovation (2005), OECD Transition Economies, Volume 2005, Number 22, September 2005, pp. i-435 Centre for Educational Research and Innovation (2002), OECD Indicators Volume, 2002, Edition pp. I376(377) pp. I-376(377) Government, A. (2007) Australian Education International (Online). Hofstede, Geert. 2001. Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions, and Organizations across Nations. Second Edition. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. Hofstede, G. (1994), “The business of international business is culture”, International Business Review, Vol. 3 No. 1, pp. 1-14. Hofstede, G. 1980. Culture’s consequences: International differences in work-related values. Newbury Park, CA: Sage. Hofstede, G. and Bond, M.H. (1984). Hofstede’s cultural dimensions: an independent validation using Rokeach’s value survey. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 15 Holden, N. (2004). “Why marketers need a new concept of culture for the global knowledge economy”, International Marketing Review, 21(6) pp. 563-572. Janosik, R. J. (1987). Rethinking the culture-negotiation link. Negotiation Journal, 3, 385-95 Kluchohn, C. and Strotbeck, F. (1961). Variations in value orientations. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. Komin, S. (1991), Psychology of the Thai People: Values and Behavioral Patterns, National Institute of Development Administration, Bangkok Knutson, T.J. (1994), “Comparison of Thai and US American cultural values: ‘mai pen rai’ versus ‘just do it’”, ABAC Journal, Vol. 14 No. 3, Bangkok, pp. 1-38. Larsen, K. A. V.-L., S. (2002) International Trade in Educational Services: Good or Bad. OECD: Higher Education Management and Policy, 14. Mazzarol & Soutar, (2002)” Push and Pull factors influencing student destination choice”, International Journal of Educational Management 16/2 pp.82-90 Ng, S.I., Lee, J.A., Soutar, G.S (2007). “Are Hofstede’s and Schwartz’s value frameworks congruent? International Marketing Review 24(2) Noypayak, W., and Speece, M. (1998), Tactics to influence subordinates among Thai managers. Journal of Managerial Psychology, Vol. 13, Issue 5/6 Pfahl, M. & Chomngam, P. & Hale, C.L. (2007). “Understanding friendship from a Thai point of view: Negotiating the expectations involved in work and non-work relationships”, China Media Research3 (4) 14 Pimpa, N. (2002). The influence of family on Thai students’ choices of international education, International Journal on Education Management 17 (5) 211 Rokeach, M. (1973). The nature of human values. New York, NY: Free Press. Sagiv, L., & Schwartz, S. H. (2000). Value priorities and subjective well-being: Direct relations and congruity effects. European Journal of Social Psychology, 30, 177-198. Sagiz, H.L. & Schwartz, S. H. (1995). Identifying culture-specifics in the content and structure of values. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 26 (1): p. 92-116 Schwartz, S.H. (2008). Values: Culture and Individual. Chapter to appear in S. M. Breugelmans, A. Chasiotis, & F. J. R. van de Vijver (Eds.), Fundamental questions in cross-cultural psychology Schwartz, S.H. (2006). Basic human values: Theory, measurement, and applications Revue française de sociologie, 47(4) Schwartz, S. H. (2006). Value orientations: Measurement, antecedents and consequences across nations. In Jowell, R., Roberts, C., Fitzgerald, R. & Eva, G. (Eds.) Measuring attitudes cross-nationally lessons from the European Social Survey. London: Sage. Schwartz, S. H. (2005a). Basic human values: Their content and structure across countries. In A. Tamayo & J. B. Porto (Eds.), Valores e comportamento nas organizações [Values and behavior in organizations] pp. 21-55. Petrópolis, Brazil: Vozes. Schwartz, S. H. (2005b). Robustness and fruitfulness of a theory of universals in individual human values. In A. Tamayo & J. B. Porto (Eds.), idem pp. 56-95. Schwartz, S. 1999. Cultural value differences: some implications for work, Applied Psychology: An International Review, Vol. 48, pp 23-48 Schwartz, S.H. (1996). Value priorities and behavior: Applying a theory of integrated value systems. In C. Seligman, J.M. Olson, & M.P. Zanna (Eds.), The psychology of values: The Ontario Symposium, Vol. 8 (pp.1-24). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum Schwartz, S. H. (1994) Are there universal aspects in the structure and contents of human values? Journal of Social Issues, 50, 19-45. Schwartz, S. 1994. Beyond individualism/collectivism: New cultural dimensions of values. In Individualism and collectivism, edited by U. Kim, H.C.Triandis, and G.Yoon. London: Sage. Schwartz, S. H. (1992). Universals in the content and structure of values: Theory and empirical tests in 20 countries. In M. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 25) (pp. 1-65). New York: Academic Press. Schwartz, S. H. (1990). Individualism and collectivism: Critique and proposed refinements. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 21 p. 139-157 Schwartz, S. H. & Bilsky, W. (1987). Toward a psychological structure of human values. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53: p. 550-562 15 Spini, D. (2003) Measurement Equivalence of 10 Value Types from the Schwartz Value Survey across 21 Countries. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 34. 16