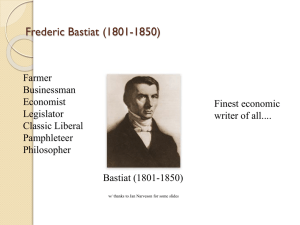

Critique of Bastiat's The Law

advertisement